The Ideology and Aesthetics of Andrew Lloyd Webber's Musicals

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

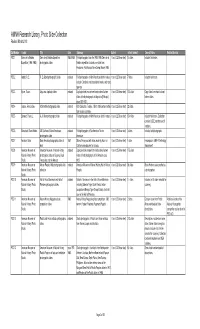

AMNH Research Library, Photo Slide Collection Revised March 2013

AMNH Research Library, Photo Slide Collection Revised March 2013 Call Number Creator Title Date Summary Extent Extent (format) General Notes Related Archival PSC 1 Cerro de la Neblina Cerro de la Neblina Expedition 1984-1989 Field photographs from the 1984-1985 Cerro de la 1 box (0.25 linear feet) 14 slides Includes field notes. Expedition (1984-1985) photographic slides Neblina expedition. Includes one slide from Amazonas, Rio Mavaca Base Camp, March 1989. PSC 2 Abbott, R. E. R. E. Abbott photographic slides undated Field photographs of North American birds in nature, 1 box (0.25 linear feet) 7 slides Includes field notes. includes Cardinals, red-shouldered hawks, and song sparrow. PSC 3 Byron, Oscar. Abyssinia duplicate slides undated Duplicate slides made from hand-colored lantern 1 box (0.25 linear feet) 100 slides Copy slides from hand colored slides of field photographs in Abyssinia [Ethiopia] lantern slides. circa 1920-1921. PSC 4 Jaques, Francis Lee. ACA textile photographic slides undated ACA Collection. Textiles, 15th to 18th century textiles 1 box (0.25 linear feet) 22 slides from various countries. PSC 5 Bierwert, Thane L. A. A. Allen photographic slides undated Field photographs of North American birds in nature. 1 box (0.25 linear feet) 154 slides Includes field notes. Collection contains USDE numbers and K numbers. PSC 6 Blanchard, Dean Hobbs. AG Southwest Native Americans undated Field photographs of Southwestern Native 1 box (0.25 linear feet) 3 slides Includes field photographs. photographic slides Americans PSC 7 Amadon, Dean Dean Amadon photographic slides of 1957 Slide of fence post with holes made by Acorn or 1 box (0.25 linear feet) 1 slide Fence post in AMNH Ornithology birds California woodpecker for storage. -

The Seven Ages of Musical Theatre: the Life Cycle of the Child Performer

UNIVERSITY OF SOUTHAMPTON The Seven Ages of Musical Theatre: The life cycle of the child performer by Lyndsay Barnbrook A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Humanities Faculty School of Music April 2016 \A person's a person, no matter how small." Dr. Seuss UNIVERSITY OF SOUTHAMPTON Abstract Humanities Faculty School of Music Doctor of Philosophy The Seven Ages of Musical Theatre: The life cycle of the child performer by Lyndsay Barnbrook The purpose of the research reported here is to explore the part played by children in musical theatre. It aims to do this on two levels. It presents, for the first time, an historical analysis of involvement of children in theatre from its earliest beginnings to the current date. It is clear from this analysis that the role children played in the evolution of theatre has been both substantial and influential, with evidence of a number of recurring themes. Children have invariably made strong contributions in terms of music, dance and spectacle, and have been especially prominent in musical comedy. Playwrights have exploited precocity for comedic purposes, innocence to deliver difficult political messages in a way that is deemed acceptable by theatre audiences, and youth, recognising the emotional leverage to be obtained by appealing to more primitive instincts, notably sentimentality and, more contentiously, prurience. Every age has had its child prodigies and it is they who tend to make the headlines. However the influence of educators and entrepreneurs, artistically and commercially, is often underestimated. Although figures such as Wescott, Henslowe and Harris have been recognised by historians, some of the more recent architects of musical theatre, like Noreen Bush, are largely unheard of outside the theatre community. -

A Weekend of Conversation and Celebration

#balliolwomen www.balliol.ox.ac.uk/balliol-women-40 A weekend of conversation and celebration Friday 27 September to Sunday 29 September 2019 BALLIOL COLLEGE WELCOME FROM THE MASTER When we first started planning for this weekend to mark the 40th anniversary of women being admitted to Balliol as students, we were very conscious of two things: that Balliol women would want much more than (however enjoyable) a party, and that they would want to be deeply involved in the planning and the events. We are enormously grateful for all the ideas and offers of help we received (not all of which we could accommodate in 36 hours). Out of this rich mix came the idea of ‘conversation and celebration’, encompassing serious conversations about serious issues for women in 2019, alongside a celebration of community, aspiration and all that Balliol’s women have achieved since 1979. While we are all painfully aware that the fight for gender equality, in all its aspects, still goes on, we hope that you will leave Balliol cheered, energised and inspired to play a part in whatever the next challenge may be. Dame Helen Ghosh DCB ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS With thanks to the Development Office, Steering Committee, Publications & Web Officer, Conference & Events Manager, Library staff, Front of House team, Kitchen staff, Porters, student helpers and everyone else who has helped with this event. Thanks also to Veroni (illustrator), Becky Clarke Design (designer) and Thomas Leach Colour (printer) for their work on this programme. PROGRAMME SATURDAY 28 SEPTEMBER 8.15–9.30am -

Making Musical Magic Live

Making Musical Magic Live Inventing modern production technology for human-centric music performance Benjamin Arthur Philips Bloomberg Bachelor of Science in Computer Science and Engineering Massachusetts Institute of Technology, 2012 Master of Sciences in Media Arts and Sciences Massachusetts Institute of Technology, 2014 Submitted to the Program in Media Arts and Sciences, School of Architecture and Planning, in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Media Arts and Sciences at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology February 2020 © 2020 Massachusetts Institute of Technology. All Rights Reserved. Signature of Author: Benjamin Arthur Philips Bloomberg Program in Media Arts and Sciences 17 January 2020 Certified by: Tod Machover Muriel R. Cooper Professor of Music and Media Thesis Supervisor, Program in Media Arts and Sciences Accepted by: Tod Machover Muriel R. Cooper Professor of Music and Media Academic Head, Program in Media Arts and Sciences Making Musical Magic Live Inventing modern production technology for human-centric music performance Benjamin Arthur Philips Bloomberg Submitted to the Program in Media Arts and Sciences, School of Architecture and Planning, on January 17 2020, in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Media Arts and Sciences at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology Abstract Fifty-two years ago, Sergeant Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band redefined what it meant to make a record album. The Beatles revolution- ized the recording process using technology to achieve completely unprecedented sounds and arrangements. Until then, popular music recordings were simply faithful reproductions of a live performance. Over the past fifty years, recording and production techniques have advanced so far that another challenge has arisen: it is now very difficult for performing artists to give a live performance that has the same impact, complexity and nuance as a produced studio recording. -

Nagy Rock 'N' Roll Könyv

Szakács Gábor Nagy rock ʼnʼ roll könyv Szakács Gábor „Ahogy SzakácsSzakács GáborGábor mondjamondja aa műfajábanműfajában egyedülegyedülálló álló Nagy rock’n’rollOzzy Osbourne: c. könyvében: …el kell döntenünk, hogy zajt vagy zenét aka- runk„Amikor hallani.” fiam rehabilitációján megismertem a szerek mélységét, és ez hasonló a heroinhoz, teljesen ledöbbentem.Juhász Kristóf: 55 éves Magyar vagyok Idők és 2017/3/7.hátralé- vô életemben újra kell gondolnom sok mindent, mivel saját magamat is hihetetlenül hosszú ideig károsítottam.” Ozzy Osbourne: „Amikor fiam rehabilitációján megismertem a szerek mélységét, és ez hasonló a heroinhoz, teljesen ledöbbentem. 55 éves vagyok és hátralévő életemben újra kell gondolnom sok mindent, mivel saját magamat is hihetetlenül hosszú ideig károsítottam.” A szerző külünköszönetet köszönetet mond mondaz Attila az ifjúságaAttila ifjúsága lemez zenészeinek:zenészeinek: Kecskés együttes: L. Kecskés András, Kecskés Péter, Herczegh László, Lévai Péter, Nagyné Bartha Anna ifjúifj.© Szakács CsoóriCsoóri Gábor, SándorLászló 2004. június Rock:ISBN Bernáth 963 216 329Tibor, X Berkes Károly, Bóta Zsolt, Horváth János, Hor- váth Menyhért, Papp Gyula, Sárdy Barbara, Szász Ferenc A szerző köszönetet mond Valkóczi Józsefnek a könyv javításáért. © Szakács Gábor, 2004. június, 2021 ISBN© Szakács 963 216Gábor, 329 2004. X június, 2021. február ISBN 963 216 329 X FOTÓK: Antal Orsolya, Ágg Károly, Becskereki Dusi, Dávid Zsolt, Galambos Anita, Knapp Zoltán, Rásonyi Mária, Tóth Tibor BORÍTÓTERV, KÉPFELDOLGOZÁS: FortekFartek Zsolt KIADVÁNYSZERKESZTÔ: Székely-Magyari Hunor KIADÓ ÉS NYOMDA: Holoprint Kft. • 1163 Bp., Veres Péter út 37. Tel.: 403-4470, fax: 402-0229, www.holoprint.hu Nagy Rock ʼnʼ Roll Könyv Tartalomjegyzék Elôszó . 4 Így kezdôdött . 6 Írók, költôk, hangadók . 15 Családok, gyermekek, utódok . 24 Indulás, feltûnés, beérkezés . -

Play-Guide Sunshine-Boys-FNL.Pdf

TABLE OF CONTENTS ABOUT ATC 1 INTRODUCTION TO THE PLAY 2 SYNOPSIS 2 MEET THE CREATOR 2 MEET THE CHARACTERS 4 COMMENTS ON THE PLAY 4 COMMENTS ON THE PLAYWRIGHT 6 THE HISTORY OF VAUDEVILLE 7 FamOUS VAUDEVILLIANS 9 A VAUDEVILLE EXCERPT: WEBER AND FIELDS 11 MEDIA TRANSITIONS: THE END OF AN ERA 12 REFERENCES IN THE PLAY 13 DISCUSSION QUESTIONS AND ACTIVITIES 19 The Sunshine Boys Play Guide written and compiled by Katherine Monberg, ATC Literary Assistant. Discussion questions and activities provided by April Jackson, Education Manager, Amber Tibbitts and Bryanna Patrick, Education Associates Support for ATC’s education and community programming has been provided by: APS John and Helen Murphy Foundation The Maurice and Meta Gross Arizona Commission on the Arts National Endowment for the Arts Foundation Bank of America Foundation Phoenix Office of Arts and Culture The Max and Victoria Dreyfus Foundation Blue Cross Blue Shield Arizona PICOR Charitable Foundation The Stocker Foundation City of Glendale Rosemont Copper The William l and Ruth T. Pendleton Community Foundation for Southern Arizona Stonewall Foundation Memorial Fund Cox Charities Target Tucson Medical Center Downtown Tucson Partnership The Boeing Company Tucson Pima Arts Council Enterprise Holdings Foundation The Donald Pitt Family Foundation Wells Fargo Ford Motor Company Fund The Johnson Family Foundation, Inc Freeport-McMoRan Copper & Gold Foundation The Lovell Foundation JPMorgan Chase The Marshall Foundation ABOUT ATC Arizona Theatre Company is a professional, not-for-profit -

KS5 Exploring Performance Styles in Musical Theatre

Exploring performance KS5 styles in Musical Theatre Heidi McEntee Heidi McEntee is a Dance and KS5 – BTEC LEVEL 3, UNIT D10 Performing Arts specialist based in the Midlands. She has worked in education for over fifteen years delivering a variety of Dance and Performing Arts qualifications at Introduction Levels 1, 2 and 3. She is a Senior Unit D10: Exploring Performance Styles is one of the three units which sit within Module D: Assessment Associate working on musical theatre Skills Development from the new BTEC Level 3 in Performing Arts Practice Performing Arts qualifications and (musical theatre) qualification. This scheme of work focuses on the first unit which introduces a contributing author for student and explores different musical theatre styles. revision guides. This unit requires learners to develop their practical skills in dance, acting and singing while furthering their understanding of musical theatre styles. The unit culminates in a performance of two extracts in two different styles of musical theatre as well as a critical review of the stylistic qualities within these extracts. This scheme of work provides a suggested approach to six weeks of introductory classes, as a part of a full timetable, which explores the development of performance styles through the history of musical theatre via practical activities, short projects and research tasks. Learning objectives By the end of this scheme, learners will have: § Investigated the history of musical theatre and the factors which have influenced its development Unit D10: Exploring Performance § Explored the characteristics of different musical theatre styles and how they have developed Styles from BTEC L3 Nationals over time Performing Arts Practice (musical § Applied stylistic conventions to the performance of material theatre) (2019) § Examined professional work through critical analysis. -

The Phantom of the Opera Music: Andrew Lloyd Webber Lyrics

The Phantom of the Opera Music: Andrew Lloyd Webber Lyrics: Charles Hart + Richard Stilgoe Book: Andrew Lloyd Webber + Richard Stilgoe Premiere: Thursday, October 9, 1986 THE STAGE OF THE PARIS OPERA, 1905 (The contents of the opera house is being auctioned off. An AUCTIONEER, PORTERS, BIDDERS, and RAOUL, seventy now, but still bright of eye. The action commences with a blow from the AUCTlONEER's gavel) AUCTIONEER Sold. Your number, sir? Thank you. Lot 663, then, ladies and gentlemen: a poster for this house's production of "Hannibal" by Chalumeau. PORTER Showing here. AUCTIONEER Do I have ten francs? Five then. Five I am bid. Six, seven. Against you, sir, seven. Eight. Eight once. Selling twice. Sold, to Raoul, Vicomte de Chagny. Lot 664: a wooden pistol and three human skulls from the 1831 production of "Robert le Diable" by Meyerbeer. Ten francs for this. Ten, thank you. Ten francs still. Fifteen, thank you, sir Fifteen I am bid. Going at fifteen. Your number, sir? 665, ladies and gentlemen: a papier-mache musical box, in the shape of a barrel-organ. Attached, the figure of a monkey in Persian robes playing the cymbals. This item, discovered in the vaults of the theatre, still in working order. PORTER (holding it up) Showing here. (He sets it in motion) AUCTIONEER My I start at twenty francs? Fifteen, then? Fifteen I am bid. (the bidding continues. RAOUL. eventually buys the box for thirty francs) Sold, for thirty francs to the Vicomte de Chagny. Thank you, sir. (The box is handed across to RAOUL. -

Hw Biography 2021

HUGH WOOLDRIDGE Director and Lighting Designer; Visiting Professor Hugh Wooldridge has produced, directed and devised theatre and television productions all over the world. He has taught and given master-classes in the UK, Europe, the US, South Africa and Australia. He trained at the London Academy of Music and Dramatic Art (LAMDA) and made his West End debut as an actor in The Dame of Sark with Dame Celia Johnson. Subsequently he performed with the London Festival Ballet / English National Ballet in the world premiere production of Romeo and Juliet choreographed by Rudolph Nureyev. At the age of 22, he directed The World of Giselle for Dame Ninette de Valois and the Royal Ballet. Since this time, he has designed lighting for new choreography with dance companies around the world including The Royal Ballet, Dance Theatre London, Rambert Dance Company, the National Youth Ballet and the English National Ballet Company. He directed the world premieres of the Graham Collier / Malcolm Lowry Jazz Suite Under A Volcano and The Undisput’d Monarch of the English Stage with Gary Bond portraying David Garrick; the Charles Strouse opera, Nightingale with Sarah Brightman at the Buxton Opera Festival; Francis Wyndham’s Abel and Cain (Haymarket, Leicester) with Peter Eyre and Sean Baker. He directed and lit the original award-winning Jeeves Takes Charge at the Lyric Hammersmith; the first productions of the Andrew Lloyd Webber and T. S. Eliot Cats (Sydmonton Festival), and the Andrew Lloyd Webber / Don Black song-cycle Tell Me 0n a Sunday with Marti Webb at the Royalty (now Peacock) Theatre; also Lloyd Webber’s Variations at the Royal Festival Hall (later combined together to become Song and Dance) and Liz Robertson’s one-woman show Just Liz compiled by Alan Jay Lerner at the Duke of York’s Theatre, London. -

English 252: Theatre in England 2006-2007 * [Optional Events

English 252: Theatre in England 2006-2007 * [Optional events — seen by some] Wednesday December 27 *2:30 p.m. Guys and Dolls (1950). Dir. Michael Grandage. Music & lyrics by Frank Loesser, Book by Jo Swerling and Abe Burrows. Based on a story and characters of Damon Runyon. Designer: Christopher Oram. Choreographer: Rob Ashford. Cast: Alex Ferns (Nathan Detroit), Samantha Janus (Miss Adelaide), Amy Nuttal (Sarah Brown), Norman Bowman (Sky Masterson), Steve Elias (Nicely Nicely Johnson), Nick Cavaliere (Big Julie), John Conroy (Arvide Abernathy), Gaye Brown (General Cartwright), Jo Servi (Lt. Brannigan), Sebastien Torkia (Benny Southstreet), Andrew Playfoot (Rusty Charlie/ Joey Biltmore), Denise Pitter (Agatha), Richard Costello (Calvin/The Greek), Keisha Atwell (Martha/Waitress), Robbie Scotcher (Harry the Horse), Dominic Watson (Angie the Ox/MC), Matt Flint (Society Max), Spencer Stafford (Brandy Bottle Bates), Darren Carnall (Scranton Slim), Taylor James (Liverlips Louis/Havana Boy), Louise Albright (Hot Box Girl Mary-Lou Albright), Louise Bearman (Hot Box Girl Mimi), Anna Woodside (Hot Box Girl Tallulha Bloom), Verity Bentham (Hotbox Girl Dolly Devine), Ashley Hale (Hotbox Girl Cutie Singleton/Havana Girl), Claire Taylor (Hot Box Girl Ruby Simmons). Dance Captain: Darren Carnall. Swing: Kate Alexander, Christopher Bennett, Vivien Carter, Rory Locke, Wayne Fitzsimmons. Thursday December 28 *2:30 p.m. George Gershwin. Porgy and Bess (1935). Lyrics by DuBose Heyward and Ira Gershwin. Book by Dubose and Dorothy Heyward. Dir. Trevor Nunn. Design by John Gunter. New Orchestrations by Gareth Valentine. Choreography by Kate Champion. Lighting by David Hersey. Costumes by Sue Blane. Cast: Clarke Peters (Porgy), Nicola Hughes (Bess), Cornell S. John (Crown), Dawn Hope (Serena), O-T Fagbenie (Sporting Life), Melanie E. -

Trent 91; First Steps Towards a Stylistic Classification (Revised 2019 Version of My 2003 Paper, Originally Circulated to Just a Dozen Specialists)

Trent 91; first steps towards a stylistic classification (revised 2019 version of my 2003 paper, originally circulated to just a dozen specialists). Probably unreadable in a single sitting but useful as a reference guide, the original has been modified in some wording, by mention of three new-ish concordances and by correction of quite a few errors. There is also now a Trent 91 edition index on pp. 69-72. [Type the company name] Musical examples have been imported from the older version. These have been left as they are apart from the Appendix I and II examples, which have been corrected. [Type the document Additional information (and also errata) found since publication date: 1. The Pange lingua setting no. 1330 (cited on p. 29) has a concordance in Wr2016 f. 108r, whereti it is tle]textless. (This manuscript is sometimes referred to by its new shelf number Warsaw 5892). The concordance - I believe – was first noted by Tom Ward (see The Polyphonic Office Hymn[T 1y4p0e0 t-h15e2 d0o, cpu. m21e6n,t se suttbtinigt lneo] . 466). 2. Page 43 footnote 77: the fragmentary concordance for the Urbs beata setting no. 1343 in the Weitra fragment has now been described and illustrated fully in Zapke, S. & Wright, P. ‘The Weitra Fragment: A Central Source of Late Medieval Polyphony’ in Music & Letters 96 no. 3 (2015), pp. 232-343. 3. The Introit group subgroup ‘I’ discussed on p. 34 and the Sequences discussed on pp. 7-12 were originally published in the Ex Codicis pilot booklet of 2003, and this has now been replaced with nos 148-159 of the Trent 91 edition. -

European Modernism and the Resident Theatre Movement: The

European Modernism and the Resident Theatre Movement: The Transformation of American Theatre between 1950 and 1970 Sarah Guthu A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Washington 2013 Reading Committee: Thomas E Postlewait, Chair Sarah Bryant-Bertail Stefka G Mihaylova Program Authorized to Offer Degree: School of Drama © Copyright 2013 Sarah Guthu University of Washington Abstract European Modernism and the Resident Theatre Movement: The Transformation of American Theatre between 1950 and 1970 Sarah Guthu Chair of the Supervisory Committee: Dr. Thomas E Postlewait School of Drama This dissertation offers a cultural history of the arrival of the second wave of European modernist drama in America in the postwar period, 1950-1970. European modernist drama developed in two qualitatively distinct stages, and these two stages subsequently arrived in the United States in two distinct waves. The first stage of European modernist drama, characterized predominantly by the genres of naturalism and realism, emerged in Europe during the four decades from the 1890s to the 1920s. This first wave of European modernism reached the United States in the late 1910s and throughout the 1920s, coming to prominence through productions in New York City. The second stage of European modernism dates from 1930 through the 1960s and is characterized predominantly by the absurdist and epic genres. Unlike the first wave, the dramas of the second wave of European modernism were not first produced in New York. Instead, these plays were often given their premieres in smaller cities across the United States: San Francisco, Seattle, Cleveland, Hartford, Boston, and New Haven, in the regional theatres which were rapidly proliferating across the United States.