Morphogenesis in the Moss Physcomitrell4 Patens

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Anthocerotophyta

Glime, J. M. 2017. Anthocerotophyta. Chapt. 2-8. In: Glime, J. M. Bryophyte Ecology. Volume 1. Physiological Ecology. Ebook 2-8-1 sponsored by Michigan Technological University and the International Association of Bryologists. Last updated 5 June 2020 and available at <http://digitalcommons.mtu.edu/bryophyte-ecology/>. CHAPTER 2-8 ANTHOCEROTOPHYTA TABLE OF CONTENTS Anthocerotophyta ......................................................................................................................................... 2-8-2 Summary .................................................................................................................................................... 2-8-10 Acknowledgments ...................................................................................................................................... 2-8-10 Literature Cited .......................................................................................................................................... 2-8-10 2-8-2 Chapter 2-8: Anthocerotophyta CHAPTER 2-8 ANTHOCEROTOPHYTA Figure 1. Notothylas orbicularis thallus with involucres. Photo by Michael Lüth, with permission. Anthocerotophyta These plants, once placed among the bryophytes in the families. The second class is Leiosporocerotopsida, a Anthocerotae, now generally placed in the phylum class with one order, one family, and one genus. The genus Anthocerotophyta (hornworts, Figure 1), seem more Leiosporoceros differs from members of the class distantly related, and genetic evidence may even present -

![Recq Helicases Function in Development, DNA Repair, and Gene Targeting in Physcomitrella Patens[OPEN]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/6959/recq-helicases-function-in-development-dna-repair-and-gene-targeting-in-physcomitrella-patens-open-276959.webp)

Recq Helicases Function in Development, DNA Repair, and Gene Targeting in Physcomitrella Patens[OPEN]

The Plant Cell, Vol. 30: 717–736, March 2018, www.plantcell.org ã 2018 ASPB. RecQ Helicases Function in Development, DNA Repair, and Gene Targeting in Physcomitrella patensOPEN Gertrud Wiedemann,a Nico van Gessel,a Fabian Köchl,a Lisa Hunn,a Katrin Schulze,b Lina Maloukh,c Fabien Nogué,c Eva L. Decker,a Frank Hartung,b,1 and Ralf Reskia,d,1 a Plant Biotechnology, Faculty of Biology, University of Freiburg, 79104 Freiburg, Germany b Julius Kuehn Institute, Institute for Biosafety in Plant Biotechnology, 06484 Quedlinburg, Germany c Institut Jean-Pierre Bourgin, INRA, AgroParisTech, CNRS, Université Paris-Saclay, 78000 Versailles, France Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/plcell/article/30/3/717/6099120 by guest on 28 September 2021 d BIOSS Centre for Biological Signalling Studies, University of Freiburg, 79104 Freiburg, Germany ORCID IDs: 0000-0002-0606-246X (N.v.G.); 0000-0003-0619-4638 (F.N.); 0000-0002-2356-6707 (F.H.); 0000-0002-5496-6711 (R.R.) RecQ DNA helicases are genome surveillance proteins found in all kingdoms of life. They are characterized best in humans, as mutations in RecQ genes lead to developmental abnormalities and diseases. To better understand RecQ functions in plants we concentrated on Arabidopsis thaliana and Physcomitrella patens, the model species predominantly used for studies on DNA repair and gene targeting. Phylogenetic analysis of the six P. patens RecQ genes revealed their orthologs in humans and plants. Because Arabidopsis and P. patens differ in their RecQ4 and RecQ6 genes, reporter and deletion moss mutants were generated and gene functions studied in reciprocal cross-species and cross-kingdom approaches. -

Chapter 23: the Early Tracheophytes

Chapter 23 The Early Tracheophytes THE LYCOPHYTES Lycopodium Has a Homosporous Life Cycle Selaginella Has a Heterosporous Life Cycle Heterospory Allows for Greater Parental Investment Isoetes May Be the Only Living Member of the Lepidodendrid Group THE MONILOPHYTES Whisk Ferns Ophioglossalean Ferns Horsetails Marattialean Ferns True Ferns True Fern Sporophytes Typically Have Underground Stems Sexual Reproduction Usually Is Homosporous Fern Have a Variety of Alternative Means of Reproduction Ferns Have Ecological and Economic Importance SUMMARY PLANTS, PEOPLE, AND THE ENVIRONMENT: Sporophyte Prominence and Survival on Land PLANTS, PEOPLE, AND THE ENVIRONMENT: Coal, Smog, and Forest Decline THE OCCUPATION OF THE LAND PLANTS, PEOPLE, AND THE The First Tracheophytes Were ENVIRONMENT: Diversity Among the Ferns Rhyniophytes Tracheophytes Became Increasingly Better PLANTS, PEOPLE, AND THE Adapted to the Terrestrial Environment ENVIRONMENT: Fern Spores Relationships among Early Tracheophytes 1 KEY CONCEPTS 1. Tracheophytes, also called vascular plants, possess lignified water-conducting tissue (xylem). Approximately 14,000 species of tracheophytes reproduce by releasing spores and do not make seeds. These are sometimes called seedless vascular plants. Tracheophytes differ from bryophytes in possessing branched sporophytes that are dominant in the life cycle. These sporophytes are more tolerant of life on dry land than those of bryophytes because water movement is controlled by strongly lignified vascular tissue, stomata, and an extensive cuticle. The gametophytes, however still require a seasonally wet habitat, and water outside the plant is essential for the movement of sperm from antheridia to archegonia. 2. The rhyniophytes were the first tracheophytes. They consisted of dichotomously branching axes, lacking roots and leaves. They are all extinct. -

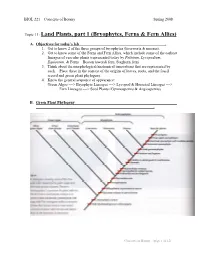

Topic 11: Land Plants, Part 1 (Bryophytes, Ferns & Fern Allies)

BIOL 221 – Concepts of Botany Spring 2008 Topic 11: Land Plants, part 1 (Bryophytes, Ferns & Fern Allies) A. Objectives for today’s lab . 1. Get to know 2 of the three groups of bryophytes (liverworts & mosses). 2. Get to know some of the Ferns and Fern Allies, which include some of the earliest lineages of vascular plants (represented today by Psilotum, Lycopodium, Equisetum, & Ferns—Boston (sword) fern, Staghorn fern) 3. Think about the morphological/anatomical innovations that are represented by each. Place these in the context of the origins of leaves, roots, and the fossil record and green plant phylogeny. 4. Know the general sequence of appearance: Green Algae ==> Bryophyte Lineages ==> Lycopod & Horsetail Lineages ==> Fern Lineages ==> Seed Plants (Gymnosperms & Angiosperms) B. Green Plant Phylogeny . Concepts of Botany, (page 1 of 12) C. NonVascular Free-Sporing Land Plants (Bryophytes) . C1. Liverworts . a. **LIVING MATERIAL**: Marchantia &/or Conacephalum (thallose liverworts). The conspicuous green plants are the gametophytes. With a dissecting scope, observe the polygonal outlines of the air chambers. On parts of the thallus are drier, it is easy to see the pore opening to the chamber. These are not stomata. They cannot open and close and the so the thallus can easily dry out if taking from water. Note the gemmae cups on some of that thalli. Ask your instructor what these are for. DRAW THEM TOO. b. **SLIDES**. Using the compound microscope, make observations of the vegetative and reproductive parts of various liverwort species. Note the structure of the air-chambers and the photosynthetic cells inside on the Marchantia sections! Concepts of Botany, (page 2 of 12) C2. -

A Polycomb Repressive Complex 2 Gene Regulates Apogamy and Gives Evolutionary Insights Into Early Land Plant Evolution

A polycomb repressive complex 2 gene regulates apogamy and gives evolutionary insights into early land plant evolution Yosuke Okanoa,1, Naoki Aonoa,1, Yuji Hiwatashia,b, Takashi Murataa,b, Tomoaki Nishiyamac,d, Takaaki Ishikawaa, Minoru Kuboc, and Mitsuyasu Hasebea,b,c,2 aNational Institute for Basic Biology, Okazaki 444-8585, Japan; bSchool of Life Science, The Graduate University for Advanced Studies, Okazaki 444-8585, Japan; cERATO, Japan Science and Technology Agency, Okazaki 444-8585, Japan; and dAdvanced Science Research Center, Kanazawa University, Kanazawa 920-0934, Japan Edited by Peter R. Crane, The University of Chicago, Chicago, IL, and approved July 27, 2009 (received for review June 22, 2009) Land plants have distinct developmental programs in haploid ogy, development, and evolution (5–7), the gene regulatory (gametophyte) and diploid (sporophyte) generations. Although network remains undeciphered. usually the two programs strictly alternate at fertilization and Parthenogenetic development of egg cells has been observed meiosis, one program can be induced during the other program. In in some alleles of loss-of-function mutants of the Arabidopsis a process called apogamy, cells of the gametophyte other than the thaliana genes FERTILIZATION-INDEPENDENT SEED 2 egg cell initiate sporophyte development. Here, we report for the (FIS2), MEDEA (MEA), and MULTICOPY SUPPRESSOR OF moss Physcomitrella patens that apogamy resulted from deletion IRA 1 (MSI1) (8, 9), which encode members of the polycomb of the gene orthologous to the Arabidopsis thaliana CURLY LEAF repressive complex 2 (PRC2) (8, 10, 11). The PRC2 complex was (PpCLF), which encodes a component of polycomb repressive first characterized in Drosophila melanogaster as a regulator of complex 2 (PRC2). -

Gametophore Buds

Glime, J. M. 2017. Ecophysiology of Development: Gametophore Buds. Chapt. 5-4. In: Glime, J. M. Bryophyte Ecology. Volume 1. 5-4-1 Physiological Ecology. Ebook sponsored by Michigan Technological University and the International Association of Bryologists. Last updated 17 July 2020 and available at <http://digitalcommons.mtu.edu/bryophyte-ecology/>. CHAPTER 5-4 ECOPHYSIOLOGY OF DEVELOPMENT: GAMETOPHORE BUDS TABLE OF CONTENTS Establishment Success ........................................................................................................................................ 5-4-2 Light and Photoperiod ......................................................................................................................................... 5-4-3 Growth Regulators .............................................................................................................................................. 5-4-4 Cytokinins .................................................................................................................................................... 5-4-4 Auxin-Cytokinin Interaction ........................................................................................................................ 5-4-6 Ethylene ....................................................................................................................................................... 5-4-8 Interactions with Other Organisms..................................................................................................................... -

Difference Between Protenema and Prothallus

Difference Between Protonema and Prothallus www.differencebetween.com Key Difference - Protonema vs Prothallus Bryophytes and Pteridophytes are respectively non-vascular and vascular plants. Vascular plants contain xylem and phloem for the transportation of their nutrients. Therefore, bryophytes and pteridophytes differ in many ways including their life cycles. In Bryophyte life cycle, the dominant stage is the gametophyte, and in pteridophytes, the dominant stage is the sporophyte. Protonema and Prothallus are two types of gametophytes belonging to bryophytes' and pteridophytes' life cycles. The protonema is a filamentous threadlike structure while the prothallus is a heart-shaped structure with many rhizoids beneath it and contains both female and male reproductive units. This is the key difference between protonema and prothallus. What is a Protonema? In the context of mosses and liverworts life cycles, the protonema is a structure which appears as threads that developed during the very early stage. Protonema develops at the initiation of the moss development after the spore germination. Then through different sequential developments stages, the protonema develops into leafy shoots which are referred to as gametophores. The protonema is an algal-like filamentous structure. It is a characteristic feature of all mosses and many of the liverworts. In hornworts (a type of liverworts) the protonema stage is absent, and it is considered as an exceptional thing with consideration to the liverworts. The protonema represents a typical gametophyte. A protonema develops through apical cell division. At the specific stage of this development cycle, phytohormone cytokinin influences the budding of three faced apical cells. The buds finally become gametophores. The gametophores are structures that mimic stems and leaves of bryophytes since they lack true stems and true leaves. -

Volume 1, Chapter 5-3: Ecophysiology of Development: Protonemata

Glime, J. M. 2017. Ecophysiology of Development: Protonemata. Chapt. 5-3. In: Glime, J. M. Bryophyte Ecology. Volume 1. 5-3-1 Physiological Ecology. Ebook sponsored by Michigan Technological University and the International Association of Bryologists. Last updated 17 July 2020 and available at <http://digitalcommons.mtu.edu/bryophyte-ecology/>. CHAPTER 5-3 ECOPHYSIOLOGY OF DEVELOPMENT: PROTONEMATA TABLE OF CONTENTS The Protonema .................................................................................................................................................... 5-3-2 Water Relations ................................................................................................................................................... 5-3-5 Seasonal Light/Temperature Changes ................................................................................................................. 5-3-5 Light .................................................................................................................................................................... 5-3-6 Light Intensity .............................................................................................................................................. 5-3-6 Light Quality ................................................................................................................................................ 5-3-9 Photoperiod ............................................................................................................................................... -

Usefulness of Physcomitrella Patens for Studying Plant Organogenesis Sandrine Bonhomme, Fabien Nogué, Catherine Rameau, Didier Schaefer

Usefulness of physcomitrella patens for studying plant organogenesis Sandrine Bonhomme, Fabien Nogué, Catherine Rameau, Didier Schaefer To cite this version: Sandrine Bonhomme, Fabien Nogué, Catherine Rameau, Didier Schaefer. Usefulness of physcomitrella patens for studying plant organogenesis. Plant Organogenesis: Methods and Protocols, 959, Humana Press, 2013, Methods in Molecular Biology. hal-01203967 HAL Id: hal-01203967 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-01203967 Submitted on 6 Jun 2020 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Chapter 2 Usefulness of Physcomitrella patens for Studying Plant Organogenesis Sandrine Bonhomme , Fabien Nogué , Catherine Rameau , and Didier G. Schaefer Abstract In this chapter, we review the main organogenesis features and associated regulation processes of the moss Physcomitrella patens (P. patens) , the model plant for the Bryophytes. We highlight how the study of this descendant of the earliest plant species that colonized earth, brings useful keys to understand the mecha- nisms that determine and control both vascular and non vascular plants organogenesis. Despite its simple morphogenesis pattern, P. patens still requires the fi ne tuning of organogenesis regulators, including hormone signalling, common to the whole plant kingdom, and which study is facilitated by a high number of molecular tools, among which the powerful possibility of gene targeting/replacement. -

Morphology of Mosses (Phylum Bryophyta)

Morphology of Mosses (Phylum Bryophyta) Barbara J. Crandall-Stotler Sharon E. Bartholomew-Began With over 12,000 species recognized worldwide (M. R. Superclass IV, comprising only Andreaeobryum; and Crosby et al. 1999), the Bryophyta, or mosses, are the Superclass V, all the peristomate mosses, comprising most most speciose of the three phyla of bryophytes. The other of the diversity of mosses. Although molecular data have two phyla are Marchantiophyta or liverworts and been undeniably useful in identifying the phylogenetic Anthocerotophyta or hornworts. The term “bryophytes” relationships among moss lineages, morphological is a general, inclusive term for these three groups though characters continue to provide definition of systematic they are only superficially related. Mosses are widely groupings (D. H. Vitt et al. 1998) and are diagnostic for distributed from pole to pole and occupy a broad range species identification. This chapter is not intended to be of habitats. Like liverworts and hornworts, mosses an exhaustive treatise on the complexities of moss possess a gametophyte-dominated life cycle; i.e., the morphology, but is aimed at providing the background persistent photosynthetic phase of the life cycle is the necessary to use the keys and diagnostic descriptions of haploid, gametophyte generation. Sporophytes are this flora. matrotrophic, permanently attached to and at least partially dependent on the female gametophyte for nutrition, and are unbranched, determinate in growth, Gametophyte Characters and monosporangiate. The gametophytes of mosses are small, usually perennial plants, comprising branched or Spore Germination and Protonemata unbranched shoot systems bearing spirally arranged leaves. They rarely are found in nature as single isolated A moss begins its life cycle when haploid spores are individuals, but instead occur in populations or colonies released from a sporophyte capsule and begin to in characteristic growth forms, such as mats, cushions, germinate. -

Download Full Article in PDF Format

Cryptogamie, Bryologie, 2016, 37 (4): 383-397 © 2016 Adac. Tous droits réservés From spore germination to gametophyte development: the culture, propagation and anatomical protonemal structure of Takakia lepidozioides (Bryophyta) in Tibet Plateau Run-Jie ZHANG a*, Wen-Jie PENG a*, Wei-Zhong LIU b, Xue-Dong LI a** & Yi-Kun HE a** aCollege of Life Sciences, Capital Normal University, Beijing 100048, China bCollege of Life Sciences, Shanxi Normal University, Shanxi Linfen 041004, China Abstract – Takakia lepidozioides is a rare and potentially relictual species of a genus that diverged early in the evolution history of mosses. Plants of Takakia grow very slowly in the wild and are almost too small (only ~ 5 mm high) to be genetically manipulated. We collected Takakia plants with mature spore-bearing capsules from the Nyingchi region at about 4,000 meters elevation in the Tibetan Plateau. We analyzed the pH and inorganic elements of the soil below the population to then optimize the composition of the Beneck medium that is generally suitable for moss culture. We explored the effects of several factors on spore germination and gametophyte growth and established the conditions for efficient spore germination and rapid gametophyte propagation. The characterization of spore germination and early gametophyte development revealed that the sporeling of Takakia is thalloid as in Sphagnum and Andreaea. These results provide the foundation to facilitate genetic, physiological and biochemical research with T. lepidozioides and also developmental studies, which may contribute to our understanding of the morphological transformations in the early diversification of mosses. Takakia lepidozioides / spore / protonema / gametophyte / propagation / Tibetan Plateau INTRODUCTION Takakia S. -

Seedless Plants

702 Chapter 25 | Seedless Plants 25.1 | Early Plant Life By the end of this section, you will be able to do the following: • Discuss the challenges to plant life on land • Describe the adaptations that allowed plants to colonize the land • Describe the timeline of plant evolution and the impact of land plants on other living things The kingdom Plantae constitutes large and varied groups of organisms. There are more than 300,000 species of catalogued plants. Of these, more than 260,000 are seed plants. Mosses, ferns, conifers, and flowering plants are all members of the plant kingdom. Land plants arose within the Archaeplastida, which includes the red algae (Rhodophyta) and two groups of green algae, Chlorophyta and Charaphyta. Most biologists also consider at least some green algae to be plants, although others exclude all algae from the plant kingdom. The reason for this disagreement stems from the fact that only green algae, the Chlorophytes and Charophytes, share common characteristics with land plants (such as using chlorophyll a and b plus carotene in the same proportion as plants). These characteristics are absent from other types of algae. Algae and Evolutionary Paths to Photosynthesis Some scientists consider all algae to be plants, while others assert that only the green algae belong in the kingdom Plantae. Still others include only the Charophytes among the plants. These divergent opinions are related to the different evolutionary paths to photosynthesis selected for in different types of algae. While all algae are photosynthetic—that is, they contain some form of a chloroplast—they didn’t all become photosynthetic via the same path.