Downloaded from Manchesterhive.Com at 09/30/2021 02:44:44AM Via Free Access

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Impact of the Illyrian Movement on the Croatian Lexicon

Slavistische Beiträge ∙ Band 223 (eBook - Digi20-Retro) George Thomas The Impact of the Illyrian Movement on the Croatian Lexicon Verlag Otto Sagner München ∙ Berlin ∙ Washington D.C. Digitalisiert im Rahmen der Kooperation mit dem DFG-Projekt „Digi20“ der Bayerischen Staatsbibliothek, München. OCR-Bearbeitung und Erstellung des eBooks durch den Verlag Otto Sagner: http://verlag.kubon-sagner.de © bei Verlag Otto Sagner. Eine Verwertung oder Weitergabe der Texte und Abbildungen, insbesondere durch Vervielfältigung, ist ohne vorherige schriftliche Genehmigung des Verlages unzulässig. «Verlag Otto Sagner» ist ein Imprint der Kubon & Sagner GmbH. George Thomas - 9783954792177 Downloaded from PubFactory at 01/10/2019 04:08:27AM via free access 00050383 S lavistische B e it r ä g e BEGRÜNDET VON ALOIS SCHMAUS HERAUSGEGEBEN VON HEINRICH KUNSTMANN PETER REHDER • JOSEF SCHRENK REDAKTION PETER REHDER Band 223 VERLAG OTTO SAGNER MÜNCHEN George Thomas - 9783954792177 Downloaded from PubFactory at 01/10/2019 04:08:27AM via free access 00050383 GEORGE THOMAS THE IMPACT OF THEJLLYRIAN MOVEMENT ON THE CROATIAN LEXICON VERLAG OTTO SAGNER • MÜNCHEN 1988 George Thomas - 9783954792177 Downloaded from PubFactory at 01/10/2019 04:08:27AM via free access ( B*y«ftecne I Staatsbibliothek l Mönchen ISBN 3-87690-392-0 © Verlag Otto Sagner, München 1988 Abteilung der Firma Kubon & Sagner, GeorgeMünchen Thomas - 9783954792177 Downloaded from PubFactory at 01/10/2019 04:08:27AM via free access 00050383 FOR MARGARET George Thomas - 9783954792177 Downloaded from PubFactory at 01/10/2019 04:08:27AM via free access .11 ж ־ י* rs*!! № ri. ur George Thomas - 9783954792177 Downloaded from PubFactory at 01/10/2019 04:08:27AM via free access 00050383 Preface My original intention was to write a book on caiques in Serbo-Croatian. -

Vladimir-Peter-Goss-The-Beginnings

Vladimir Peter Goss THE BEGINNINGS OF CROATIAN ART Published by Ibis grafika d.o.o. IV. Ravnice 25 Zagreb, Croatia Editor Krešimir Krnic This electronic edition is published in October 2020. This is PDF rendering of epub edition of the same book. ISBN 978-953-7997-97-7 VLADIMIR PETER GOSS THE BEGINNINGS OF CROATIAN ART Zagreb 2020 Contents Author’s Preface ........................................................................................V What is “Croatia”? Space, spirit, nature, culture ....................................1 Rome in Illyricum – the first historical “Pre-Croatian” landscape ...11 Creativity in Croatian Space ..................................................................35 Branimir’s Croatia ...................................................................................75 Zvonimir’s Croatia .................................................................................137 Interlude of the 12th c. and the Croatia of Herceg Koloman ............165 Et in Arcadia Ego ...................................................................................231 The catastrophe of Turkish conquest ..................................................263 Croatia Rediviva ....................................................................................269 Forest City ..............................................................................................277 Literature ................................................................................................303 List of Illustrations ................................................................................324 -

Svetozar Borevic, South Slav Habsburg Nationalism, and the First World War

University of South Florida Scholar Commons Graduate Theses and Dissertations Graduate School 4-17-2021 Fuer Kaiser und Heimat: Svetozar Borevic, South Slav Habsburg Nationalism, and the First World War Sean Krummerich University of South Florida Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.usf.edu/etd Part of the History Commons Scholar Commons Citation Krummerich, Sean, "Fuer Kaiser und Heimat: Svetozar Borevic, South Slav Habsburg Nationalism, and the First World War" (2021). Graduate Theses and Dissertations. https://scholarcommons.usf.edu/etd/8808 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Für Kaiser und Heimat: Svetozar Boroević, South Slav Habsburg Nationalism, and the First World War by Sean Krummerich A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of History College of Arts & Sciences University of South Florida Major Professor: Kees Boterbloem, Ph.D. Darcie Fontaine, Ph.D. J. Scott Perry, Ph.D. Golfo Alexopoulos, Ph.D. Date of Approval: March 30, 2021 Keywords: Serb, Croat, nationality, identity, Austria-Hungary Copyright © 2021, Sean Krummerich DEDICATION For continually inspiring me to press onward, I dedicate this work to my boys, John Michael and Riley. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This dissertation would not have been possible without the support of a score of individuals over more years than I would care to admit. First and foremost, my thanks go to Kees Boterbloem, Darcie Fontaine, Golfo Alexopoulos, and Scott Perry, whose invaluable feedback was crucial in shaping this work into what it is today. -

Jewish Citizens of Socialist Yugoslavia: Politics of Jewish Identity in a Socialist State, 1944-1974

JEWISH CITIZENS OF SOCIALIST YUGOSLAVIA: POLITICS OF JEWISH IDENTITY IN A SOCIALIST STATE, 1944-1974 by Emil Kerenji A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (History) in The University of Michigan 2008 Doctoral Committee: Professor Todd M. Endelman, Co-Chair Professor John V. Fine, Jr., Co-Chair Professor Zvi Y. Gitelman Professor Geoffrey H. Eley Associate Professor Brian A. Porter-Szűcs © Emil Kerenji 2008 Acknowledgments I would like to thank all those who supported me in a number of different and creative ways in the long and uncertain process of researching and writing a doctoral dissertation. First of all, I would like to thank John Fine and Todd Endelman, because of whom I came to Michigan in the first place. I thank them for their guidance and friendship. Geoff Eley, Zvi Gitelman, and Brian Porter have challenged me, each in their own ways, to push my thinking in different directions. My intellectual and academic development is equally indebted to my fellow Ph.D. students and friends I made during my life in Ann Arbor. Edin Hajdarpašić, Bhavani Raman, Olivera Jokić, Chandra Bhimull, Tijana Krstić, Natalie Rothman, Lenny Ureña, Marie Cruz, Juan Hernandez, Nita Luci, Ema Grama, Lisa Nichols, Ania Cichopek, Mary O’Reilly, Yasmeen Hanoosh, Frank Cody, Ed Murphy, Anna Mirkova are among them, not in any particular order. Doing research in the Balkans is sometimes a challenge, and many people helped me navigate the process creatively. At the Jewish Historical Museum in Belgrade, I would like to thank Milica Mihailović, Vojislava Radovanović, and Branka Džidić. -

Matija Majar Ziljski Enlightener, Politician, Scholar

MATIJA MAJAR ZILJSKI ENLIGHTENER, POLITICIAN, SCHOLAR ISKRA VASILJEVNA ČURKINA Matija Majar Ziljski left a significant mark in differ- Matija Majar je bistveno zaznamoval različna po- ent spheres of cultural, educational and political life. dročja kulturnega, vzgojnega in političnega življenja. During the revolution of 1848–1849, he was an Slo- Med revolucijo 1848–1849 je bil eden vodilnih slo- venian ideologist and the first to publish his political venskih mislecev in prvi, ki je objavil politični pro- program entitled United Slovenia. After the revolu- gram Zedinjena Slovenija. Po revoluciji se je postopo- tion, he gradually turned away from Pan-Slovenian ma preusmeril od vseslovenskih vprašanj v ustvarjanje affairs, the main reason for this being his idea about panslovanskega/vseslovanskega jezika. Ta usmeritev se creation of Pan-Slavic literary language. His posi- je še bolj okrepila po njegovem potovanju na Etnograf- tion on this matter strengthened after his trip to the sko razstavo v Moskvo leta 1867 in zaradi prijatelj- Ethnographic Exhibition in Moscow in 1867 and his stev z ruskimi slavofili. friendship with Russian Slavophiles. Ključne besede: Matija Majar Ziljski, biografija, Keywords: Matija Majar Ziljski, biography, Panslav- panslavizem, etnografska razstava, Moskva. ism, Ethnographic exhibition, Moscow. Matija Majar Ziljski was one of the most outstanding Slovenian national activists of the 19th century� He was born on 7 February 1809 in a small village of Wittenig- Vitenče in the Gail-Zilja river valley� His father, a -

Information to Users

INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand corner and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Each original is also photographed in one exposure and is included in reduced form at the back of the book. Photographs included in the original manuscript have been reproduced xerographically in this copy. Higher quality 6" x 9" black and white photographic prints are available for any photographs or illustrations appearing in this copy for an additional charge. Contact UMI directly to order. UMI • University Microfilms International A Bell & Howell Information Company 3 0 0 North) Z e e b Road, Ann Arbor, Ml 4 8 1 0 6 -1 3 4 6 U SA 313/761-4700 800/521-0600 Order Number 9121692 Poetics andkultura: A study of contemporary Slovene and Croat puppetry Latchis-Silverthorne, Eugenie T., Ph.D. -

The Croatian Ustasha Regime and Its Policies Towards

THE IDEOLOGY OF NATION AND RACE: THE CROATIAN USTASHA REGIME AND ITS POLICIES TOWARD MINORITIES IN THE INDEPENDENT STATE OF CROATIA, 1941-1945. NEVENKO BARTULIN A thesis submitted in fulfilment Of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of New South Wales November 2006 1 2 3 Acknowledgements I would like to thank my supervisor Dr. Nicholas Doumanis, lecturer in the School of History at the University of New South Wales (UNSW), Sydney, Australia, for the valuable guidance, advice and suggestions that he has provided me in the course of the writing of this thesis. Thanks also go to his colleague, and my co-supervisor, Günther Minnerup, as well as to Dr. Milan Vojkovi, who also read this thesis. I further owe a great deal of gratitude to the rest of the academic and administrative staff of the School of History at UNSW, and especially to my fellow research students, in particular, Matthew Fitzpatrick, Susie Protschky and Sally Cove, for all their help, support and companionship. Thanks are also due to the staff of the Department of History at the University of Zagreb (Sveuilište u Zagrebu), particularly prof. dr. sc. Ivo Goldstein, and to the staff of the Croatian State Archive (Hrvatski državni arhiv) and the National and University Library (Nacionalna i sveuilišna knjižnica) in Zagreb, for the assistance they provided me during my research trip to Croatia in 2004. I must also thank the University of Zagreb’s Office for International Relations (Ured za meunarodnu suradnju) for the accommodation made available to me during my research trip. -

Acta 108.Indd

Acta Poloniae Historica 108, 2013 PL ISSN 0001–6892 Maciej Falski CROATIAN POLITICAL DISCOURSE OF 1861 AND THE KEY CONCEPTS OF THE NINETEENTH-CENTURY PUBLIC DEBATE I INTRODUCTION The events in the Habsburg monarchy after 1859 were undoubtedly of key signifi cance to the political and social changes in Europe. Austria’s defeat in Italy and the proclaiming of a united Kingdom of Italy, the central budget’s enormous debt, German tendencies towards unifi ca- tion – it all contributed to the upsetting of the position of Austria and forced the emperor to give up absolutist rule over the country. For all countries making up the monarchy, the constitutional era, which began in 1860, marked a period of political changes, debates concerning the defi nitions of the public sphere and autonomy as well as what is most important for the functioning of political communi- ties, that is, setting goals and methods of accomplishing them. This article focuses on the shaping of the framework of public debate in Croatia in the second half of the nineteenth century. My claim is, and I shall try to substantiate it, that they were formed in 1861, over the course of the discussions resulting from the need to establish new political order in the monarchy. I am using the concept of framework as a metaphor which makes it possible to understand the way of conducting and limiting the negotiation of social meanings by public actors. Thus, the subject of the present analysis is not a dialogue of philosophers or soci- ologists representing the position of secondary and generalising analysis of social messages, but the propositions of participants in political life who have positioned themselves as ideologists informing the quality and contents of polemics related to defi ning political objectives. -

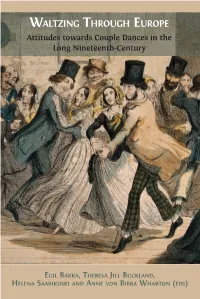

9. Dancing and Politics in Croatia: the Salonsko Kolo As a Patriotic Response to the Waltz1 Ivana Katarinčić and Iva Niemčić

WALTZING THROUGH EUROPE B ALTZING HROUGH UROPE Attitudes towards Couple Dances in the AKKA W T E Long Nineteenth-Century Attitudes towards Couple Dances in the Long Nineteenth-Century EDITED BY EGIL BAKKA, THERESA JILL BUCKLAND, al. et HELENA SAARIKOSKI AND ANNE VON BIBRA WHARTON From ‘folk devils’ to ballroom dancers, this volume explores the changing recep� on of fashionable couple dances in Europe from the eighteenth century onwards. A refreshing interven� on in dance studies, this book brings together elements of historiography, cultural memory, folklore, and dance across compara� vely narrow but W markedly heterogeneous locali� es. Rooted in inves� ga� ons of o� en newly discovered primary sources, the essays aff ord many opportuni� es to compare sociocultural and ALTZING poli� cal reac� ons to the arrival and prac� ce of popular rota� ng couple dances, such as the Waltz and the Polka. Leading contributors provide a transna� onal and aff ec� ve lens onto strikingly diverse topics, ranging from the evolu� on of roman� c couple dances in Croa� a, and Strauss’s visits to Hamburg and Altona in the 1830s, to dance as a tool of T cultural preserva� on and expression in twen� eth-century Finland. HROUGH Waltzing Through Europe creates openings for fresh collabora� ons in dance historiography and cultural history across fi elds and genres. It is essen� al reading for researchers of dance in central and northern Europe, while also appealing to the general reader who wants to learn more about the vibrant histories of these familiar dance forms. E As with all Open Book publica� ons, this en� re book is available to read for free on the UROPE publisher’s website. -

“Entire Yugoslavia, One Courtyard.” Political Mythology, Brotherhood and Unity and the “Non-National” Yugoslavness at the Sarajevo School of Rock

"All Yugoslavia Is Dancing Rock and Roll" Yugoslavness and the Sense of Community in the 1980s Yu-Rock Jovanovic, Zlatko Publication date: 2014 Document version Early version, also known as pre-print Citation for published version (APA): Jovanovic, Z. (2014). "All Yugoslavia Is Dancing Rock and Roll": Yugoslavness and the Sense of Community in the 1980s Yu-Rock. Det Humanistiske Fakultet, Københavns Universitet. Download date: 24. sep.. 2021 FACULTY OF HUMANITIE S UNIVERSITY OF COPENH AGEN PhD thesis Zlatko Jovanovic “ All Yugoslavia Is Dancing Rock and Roll” Yugoslavness and the Sense of Community in the 1980s Yu-Rock Academic advisor: Mogens Pelt Submitted: 25/11/13 INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................................. 4 Relevant Literature and the Thesis’ Contribution to the Field .................................................................................... 6 Theoretical and methodological considerations ........................................................................................................... 12 Sources ............................................................................................................................................................................. 19 The content and the methodology of presentation ....................................................................................................... 22 YUGOSLAVS, YUGOSLAVISM AND THE NOTION OF YUGOSLAV-NESS .................. 28 Who Were the Yugoslavs? “The -

A Historical Geographical Analysis of the Development of the Croatian-Hungarian Border

2014/IV. pp. 75-92. ISSN: 2062-1655 Tvrtko Josip Čelan A Historical Geographical Analysis of the Development of the Croatian-Hungarian Border ABSTRACT This paper analyses the Croatian-Hungarian boundary and state border features and gives an overview of development stages of boundary/border through the history, including Croatian accession to the European Union (EU) in 2013. The aim of this work is to define if antecedent changes have had positive impact on the Croatian-Hungarian border area. I will examine the historical geographical background of the Mura-Drava boundary/border. Next to considering all relevant European and wider literature I will compare and if necessary confront Croatian and Hungarian scientific resources. Special focus will be on assessing the role and importance of the common border and its modifications in the past, with reflection on the current period when the Republic of Croatia is an EU Member State, aiming to join soon the Schengen Area. Although the changes in Europe have been very intensive in the last twenty-five years, from the fall of the Berlin Wall to biggest ever EU enlargement process (2004-2007), the favourable historical circumstances have not been utilised in the Croatian-Hungarian border strip. This area is still suffering from large geographical handicap, presenting strong language and transport barriers. The border zone remained a strong periphery compared to the two capitals (Zagreb, Budapest) of significantly centralised states Croatia and Hungary. Keywords: Croatian-Hungarian boundary, 900 years of joint history, old European border, geographical handicap, language and transport barriers, cross-border area, European Union. IntroDuction “Boundaries are conceived of as lines separating entities from each other. -

Writing History Under the «Dictatorship of the Proletariat»: Yugoslav Historiography 1945–1991

Revista de História das Ideias Vol. 39. 2ª Série (2021) 49-73 WRITING HISTORY UNDER THE «DICTATORSHIP OF THE PROLETARIAT»: YUGOSLAV HISTORIOGRAPHY 1945–1991 Michael antolović University of Novi Sad, Faculty of Education in Sombor [email protected] https://orcid.org/0000-0003-1344-9133 Texto recebido em / Text submitted on: 17/09/2020 Texto aprovado em / Text approved on: 04/03/2021 Abstract: This paper analyzes the development of the historiography in the former socialist Yugoslavia (1945–1991). Starting with the revolutionary changes after the Second World War and the establishment of the «dictatorship of the proletariat», the paper considers the ideological surveillance imposed on historiography entailing its reconceptualization on the Marxist grounds. Despite the existence of common Yugoslav institutions, Yugoslav historiography was constituted by six historiographies focusing their research programs on the history of their own nation, i.e. the republic. Therefore, many joint historiographical projects were either left unfinished or courted controversies between historians over a number of phenomena from the Yugoslav history. Yugoslav historiography emancipated from Marxist dogmatism, and modernized itself following various forms of social history due to a gradual weakening of ideological surveillance from the 1960s onwards. However, the modernization of Yugoslav historiography was carried out only partially because of the growing social and political crises which eventually led to the dissolution of Yugoslavia. Keywords: Socialist Yugoslavia; Marxism; historiography; historical theory; ideology. https://doi.org/10.14195/2183-8925_39_2 Revista de História das Ideias Yugoslav historiography denotes the historiography developing in the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats, and Slovenes/Yugoslavia in the interwar period, as well as in socialist Yugoslavia from the end of the Second World War until the country’s disintegration at the beginning of the 1990s.