China's United Front Work in Civil Society

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Members of Board and Profiles

76 MEMBERS OF BOARD AND PROFILES MEMBERS OF THE BOARD FROM RIGHT FRONT ROW Mr Victor SO Hing-woh (Chairman), Mr Edward CHOW Kwong-fai, Mr Laurence HO Hoi-ming, Dr Lawrence POON Wing-cheung BACK ROW The Honourable Alice MAK Mei-kuen, Professor the Honourable Joseph LEE Kok-long, Mrs Cecilia WONG NG Kit-wah, The Honourable WU Chi-wai, Mr Thomas CHAN Chung-ching, Mr Evan AU YANG Chi-chun, Mr Roger LUK Koon-hoo, Mr Stanley WONG Yuen-fai, Mr Michael MA Chiu-tsee (Executive Director), Mr Raymond LEE Kai-wing 77 MEMBERS OF BOARD AND PROFILES FROM LEFT FRONT ROW Ir WAI Chi-sing (Managing Director), Mr Nelson LAM Chi-yuen, Mr Timothy MA Kam-wah BACK ROW Ms Judy CHAN Ka-pui, Dr Gregg LI G. Ka-lok, Mr Michael WONG Yick-kam, Mr Laurence LI Lu-jen, Dr CHEUNG Tin-cheung, Miss Vega WONG Sau-wai, Mr Pius CHENG Kai-wah (Executive Director), Dr the Honourable Ann CHIANG Lai-wan, Professor Eddie HUI Chi-man, Mr David TANG Chi-fai 78 MEMBERS OF BOARD AND PROFILES Chairman : Mr Victor SO Hing-woh, SBS, JP Managing Director : Ir WAI Chi-sing, GBS, JP, FHKEng Executive Directors : Mr Pius CHENG Kai-wah Mr Michael MA Chiu-tsee Non-Executive Directors (non-official): Mr Evan AU YANG Chi-chun (from 1 December 2017) Ms Judy CHAN Ka-pui Dr the Honourable Ann CHIANG Lai-wan, SBS, JP Mr Edward CHOW Kwong-fai, JP Mr Laurence HO Hoi-ming Professor Eddie HUI Chi-man, MH Mr Nelson LAM Chi-yuen Professor the Honourable Joseph LEE Kok-long, SBS, JP Dr Gregg LI G. -

Electoral Affairs Commission Report

i ABBREVIATIONS Amendment Regulation to Electoral Affairs Commission (Electoral Procedure) Cap 541F (District Councils) (Amendment) Regulation 2007 Amendment Regulation to Particulars Relating to Candidates on Ballot Papers Cap 541M (Legislative Council) (Amendment) Regulation 2007 Amendment Regulation to Electoral Affairs Commission (Financial Assistance for Cap 541N Legislative Council Elections) (Application and Payment Procedure) (Amendment) Regulation 2007 APIs announcements in public interest APRO, APROs Assistant Presiding Officer, Assistant Presiding Officers ARO, AROs Assistant Returning Officer, Assistant Returning Officers Cap, Caps Chapter of the Laws of Hong Kong, Chapters of the Laws of Hong Kong CAS Civil Aid Service CC Complaints Centre CCC Central Command Centre CCm Complaints Committee CE Chief Executive CEO Chief Electoral Officer CMAB Constitutional and Mainland Affairs Bureau (the former Constitutional and Affairs Bureau) D of J Department of Justice DC, DCs District Council, District Councils DCCA, DCCAs DC constituency area, DC constituency areas DCO District Councils Ordinance (Cap 547) ii DO, DOs District Officer, District Officers DPRO, DPROs Deputy Presiding Officer, Deputy Presiding Officers EAC or the Commission Electoral Affairs Commission EAC (EP) (DC) Reg Electoral Affairs Commission (Electoral Procedure) (District Councils) Regulation (Cap 541F) EAC (FA) (APP) Reg Electoral Affairs Commission (Financial Assistance for Legislative Council Elections and District Council Elections) (Application and Payment -

Chapter 6 Hong Kong

CHAPTER 6 HONG KONG Key Findings • The Hong Kong government’s proposal of a bill that would allow for extraditions to mainland China sparked the territory’s worst political crisis since its 1997 handover to the Mainland from the United Kingdom. China’s encroachment on Hong Kong’s auton- omy and its suppression of prodemocracy voices in recent years have fueled opposition, with many protesters now seeing the current demonstrations as Hong Kong’s last stand to preserve its freedoms. Protesters voiced five demands: (1) formal with- drawal of the bill; (2) establishing an independent inquiry into police brutality; (3) removing the designation of the protests as “riots;” (4) releasing all those arrested during the movement; and (5) instituting universal suffrage. • After unprecedented protests against the extradition bill, Hong Kong Chief Executive Carrie Lam suspended the measure in June 2019, dealing a blow to Beijing which had backed the legislation and crippling her political agenda. Her promise in September to formally withdraw the bill came after months of protests and escalation by the Hong Kong police seeking to quell demonstrations. The Hong Kong police used increasingly aggressive tactics against protesters, resulting in calls for an independent inquiry into police abuses. • Despite millions of demonstrators—spanning ages, religions, and professions—taking to the streets in largely peaceful pro- test, the Lam Administration continues to align itself with Bei- jing and only conceded to one of the five protester demands. In an attempt to conflate the bolder actions of a few with the largely peaceful protests, Chinese officials have compared the movement to “terrorism” and a “color revolution,” and have im- plicitly threatened to deploy its security forces from outside Hong Kong to suppress the demonstrations. -

香港房屋委員會及轄下小組委員會the Hong Kong Housing Authority And

香港房屋委員會及 轄下小組委員會 The Hong Kong Housing Authority and its Committees 香港房屋委員會委員 2017/18 The Hong Kong Housing Authority Members 主席 陳帆先生, JP Chairman (運輸及房屋局局長) The Honourable Frank CHAN Fan, JP (Secretary for Transport and Housing) 副主席 應耀康先生, JP(房屋署署長) Vice-Chairman Mr Stanley YING Yiu-hong, JP (Director of Housing) 委員 陳漢雲教授 張達棠先生, JP 鄭慧恩女士 Professor Edwin CHAN Mr CHEUNG Tat-tong, JP Miss Vena CHENG Wei-yan Members Hon-wan 盧偉國議員, SBS, MH, JP 盧麗華博士 李炳權先生, JP Dr the Honourable Dr Miranda LOU Lai-wah Mr LEE Ping-kuen, JP LO Wai-kwok, SBS, MH, JP 邵家輝議員 王永祥先生 雷紹麟先生 The Honourable SHIU Ka-fai Mr Winfield WONG Mr Alan LUI Siu-lun Wing-cheung 尹兆堅議員 張國鈞議員, JP The Honourable Andrew WAN 馮婉眉女士, BBS, JP The Honourable Horace Siu-kin Miss Anita FUNG Yuen-mei, CHEUNG Kwok-kwan, JP BBS, JP 財經事務及庫務局常任秘書長(庫務) 郭偉强議員, JP (財經事務及庫務局副秘書長(庫務)(2) 何周禮先生, MH The Honourable KWOK 或財經事務及庫務局首席助理秘書長 Mr Barrie HO Chow-lai, MH Wai-keung, JP (庫務)(管理會計)候補) Permanent Secretary for 許美嫦女士, MH, JP 郭榮鏗議員 Financial Services and the Ms Tennessy HUI Mei- The Honourable Treasury (Treasury) sheung, MH, JP Dennis KWOK Wing-hang (with Deputy Secretary for Financial Services and the Treasury 林雲峯教授, JP 李國麟議員, SBS, JP (Treasury) (2) Professor Bernard Vincent Professor the Honourable or Principal Assistant Secretary LIM Wan-fung, JP Joseph LEE Kok-long, for Financial Services and the SBS, JP Treasury (Treasury) (Management 劉國裕博士, JP Accounting) as her alternate) Dr LAU Kwok-yu, JP 柯創盛議員, MH The Honourable Wilson OR 地政總署署長 黃遠輝先生, SBS, JP Chong-shing, MH (地政總署副署長(一般事務)或 Mr Stanley WONG Yuen-fai, -

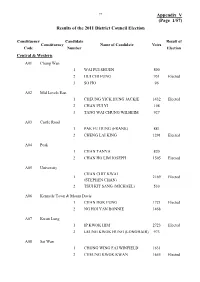

Appendix V (Page 1/57) Results of the 2011 District Council Election

97 Appendix V (Page 1/57) Results of the 2011 District Council Election Constituency Candidate Result of Constituency Name of Candidate Votes Code Number Election Central & Western A01 Chung Wan 1 WAI PUI SHUEN 800 2 HUI CHI FUNG 951 Elected 3 SO HO 96 A02 Mid Levels East 1 CHEUNG YICK HUNG JACKIE 1432 Elected 2 CHAN PUI YI 108 3 TANG WAI CHUNG WILHEIM 927 A03 Castle Road 1 PAK FU HUNG (FRANK) 881 2 CHENG LAI KING 1291 Elected A04 Peak 1 CHAN TANYA 820 2 CHAN HO LIM JOSEPH 1505 Elected A05 University CHAN CHIT KWAI 1 2169 Elected (STEPHEN CHAN) 2 TSUI KIT SANG (MICHAEL) 530 A06 Kennedy Town & Mount Davis 1 CHAN HOK FUNG 1721 Elected 2 NG HOI YAN BONNIE 1468 A07 Kwun Lung 1 IP KWOK HIM 2723 Elected 2 LEUNG KWOK HUNG (LONGHAIR) 973 A08 Sai Wan 1 CHONG WING FAI WINFIELD 1631 2 CHEUNG KWOK KWAN 1655 Elected 98 Appendix V (Page 2/57) Constituency Candidate Result of Constituency Name of Candidate Votes Code Number Election A09 Belcher 1 LAM WAI WING MALCOLM 1968 Elected 2 WONG KA LOK WILLIAM 201 3 YEUNG SUI YIN (VICTOR) 1935 A10 Shek Tong Tsui CHING MING TAT 1 705 (LOUIS CHING) 2 CHAN CHOI HI 1871 Elected A11 Sai Ying Pun 1 YUEN MAN HO 189 2 LO YEE HANG 1875 Elected 3 YONG CHAK CHEONG 711 A12 Sheung Wan 1 YIM TAT MING 270 2 CHAN YIN HO 910 3 KAM NAI WAI 1450 Elected A13 Tung Wah 1 HO CHUN KI FREDERICK 907 2 LEE SIU CHEONG 125 3 SIU KA YI 1168 Elected A14 Centre Street 1 WONG HO YIN 1199 2 LEE CHI HANG SIDNEY 1739 Elected A15 Water Street 1 YEUNG HOK MING 1241 2 WONG KIN SHING 1353 Elected 3 TAI CHEUK YIN LESLIE SPENCER 463 99 Appendix V (Page -

Minutes Have Been Seen by the Administration)

立法會 Legislative Council LC Paper No. CB(1)1313/03-04 (These minutes have been seen by the Administration) Ref : CB1/PL/PLW/1 Panel on Planning, Lands and Works Minutes of meeting held on Tuesday, 27 January 2004 at 2:30 pm in Conference Room A of the Legislative Council Building Members present : Dr Hon TANG Siu-tong, JP (Chairman) Hon LAU Ping-cheung (Deputy Chairman) Dr Hon David CHU Yu-lin, JP Ir Dr Hon Raymond HO Chung-tai, JP Hon TAM Yiu-chung, GBS, JP Hon Albert CHAN Wai-yip Hon WONG Sing-chi Hon IP Kwok-him, JP Member attending : Hon CHOY So-yuk Members absent : Hon James TIEN Pei-chun, GBS, JP Hon James TO Kun-sun Hon WONG Yung-kan Hon LAU Wong-fat, GBS, JP Hon Timothy FOK Tsun-ting, SBS, JP Hon Abraham SHEK Lai-him, JP Public officers : Agenda Item IV attending Mr TSUI Wai Principal Assistant Secretary for Environment, Transport and Works (Works) W2 - 2 - Mr James S O CHAN Acting Principal Assistant Secretary for Environment, Transport and Works (Works) W3 Mr Eddy YAU, JP Assistant Director (Leisure Services) Leisure and Cultural Services Department Dr WONG Fook-yee Assistant Director (Country and Marine Parks) Agriculture, Fisheries and Conservation Department Agenda item V Mr Jack CHAN Acting Deputy Secretary for Environment, Transport and Works (Works)W1 Mr Thomas TSO Deputy Secretary for Housing, Planning and Lands (Planning and Lands)1 Mr TSAO Tak-kiang Director of Civil Engineering Mr John CHAI Director of Territory Development Mr Albert CHENG Assistant Director (Headquarters) Civil Engineering Department Agenda items VI, -

Annex Board of Directors of the HKMC (Effective from 1 October 2019)

Annex Board of Directors of the HKMC (effective from 1 October 2019) The Hon. Paul CHAN Mo-po, GBM, GBS, MH, JP Financial Secretary (Chairman and Executive Director) Mr Eddie YUE Wai-man, JP Chief Executive (Deputy Chairman and Executive Director) Hong Kong Monetary Authority Mr Howard LEE Tat-chi, JP Deputy Chief Executive (Executive Director) Hong Kong Monetary Authority Mr Raymond LI Ling-cheung, JP Senior Executive Director (Executive Director and Chief Executive Officer) Hong Kong Monetary Authority The Hon. Jeffrey LAM Kin-fung, GBS, JP Member of Executive Council (Non-Executive Director) Member of Legislative Council Managing Director Forward Winsome Industries Limited The Hon. James Henry LAU Jr., JP Secretary for Financial Services and (Non-Executive Director) the Treasury The Hon. Frank CHAN Fan, JP Secretary for Transport and Housing (Non-Executive Director) The Hon. Horace CHEUNG Kwok-kwan, JP Member of Executive Council (Non-Executive Director) Member of Legislative Council Member of Central and Western District Council Partner, Cheung & Yeung, Solicitors The Hon. Dennis KWOK Wing-hang Member of Legislative Council (Non-Executive Director) Barrister-at-law Professor CHAN Ka-keung, GBS, JP Adjunct Professor (Non-Executive Director) The Hong Kong University of Science and Technology Mr Huen WONG, BBS, JP Principal (Hong Kong and Shanghai (Non-Executive Director) Offices) Fried, Frank, Harris, Shriver & Jacobson Ms Anita FUNG Yuen-mei, BBS, JP Director (Non-Executive Director) Hong Kong Exchanges and Clearing Limited Mr Leong CHEUNG Executive Director, Charities and (Non-Executive Director) Community The Hong Kong Jockey Club Mr Clement CHAN Kam-wing Managing Director – Assurance (Non-Executive Director) BDO Limited . -

THE HONG KONG HOUSING AUTHORITY and ITS COMMITTEES 香港房屋委員會及其小組委員會 83 the Hong Kong Housing Authority and Its Committees

香港房屋委員會及其小組委員會 THE HONG KONG HOUSING AUTHORITY AND ITS COMMITTEES 香港房屋委員會及其小組委員會 83 The Hong Kong Housing Authority and its Committees 香港房屋委員會委員 2015/16 The Hong Kong Housing Authority Members 主席 張炳良教授, GBS, JP Chairman (運輸及房屋局局長) Professor the Honourable Anthony CHEUNG Bing-leung, GBS, JP (Secretary for Transport and Housing) 副主席 應耀康先生, JP(房屋署署長) Vice-Chairman Mr Stanley YING Yiu-hong, JP (Director of Housing) 委員 蘇偉文教授, JP 劉國裕博士, JP 張宇人議員, GBS, JP Members Professor Raymond Dr LAU Kwok-yu, JP The Honourable SO Wai-man, JP Tommy CHEUNG Yu-yan, 黃遠輝先生, SBS, JP GBS, JP 區嘯翔先生, BBS Mr Stanley WONG Yuen-fai, Mr Albert AU Siu-cheung, BBS SBS, JP 郭偉强議員 The Honourable KWOK Wai-keung 劉文君女士 劉詩韻女士, JP Ms Julia LAU Man-kwan Ms Serena LAU Sze-wan, JP 郭榮鏗議員 The Honourable 黃成智先生 溫文儀先生, BBS, JP Dennis KWOK Wing-hang Mr WONG Sing-chi Mr WAN Man-yee, BBS, JP 李國麟議員, SBS, JP 陳漢雲教授 蔡海偉先生 Professor the Honourable Professor Edwin CHAN Mr CHUA Hoi-wai Joseph LEE Kok-long, SBS, JP Hon-wan 蘇晴女士 財經事務及庫務局常任秘書長(庫務) 李炳權先生, JP Ms SO Ching (財經事務及庫務局副秘書長(庫務)(2) Mr LEE Ping-kuen, JP 或財經事務及庫務局首席助理秘書長 譚小瑩女士, JP (庫務)(管理會計)候補) 王永祥先生 Ms Iris TAM Siu-ying, JP Permanent Secretary for Financial Mr Winfield WONG Services and the Treasury (Treasury) 張達棠先生 Wing-cheung (with Deputy Secretary for Financial Services Mr CHEUNG Tat-tong and the Treasury (Treasury) (2) or Principal 馮婉眉女士, BBS, JP Assistant Secretary for Financial Services Miss Anita FUNG 盧偉國議員, SBS, MH, JP and the Treasury (Treasury) (Management Yuen-mei, BBS, JP Dr the Honourable Accounting) as her alternate) LO Wai-kwok, -

香港房屋委員會及轄下小組委員會- the Hong Kong Housing Authority And

中英文可以用執垃圾,中文改稿入字或新排,不要用執垃圾,轉手動執垃圾。 文 用 EMrule 香港房屋委員會及轄下小組委員會 The Hong Kong Housing Authority and , 英 文its 用Committees ENrule 。 100 中文用英文可以用執垃圾,中文改稿入字或新排,不要用執垃圾,轉手動執垃圾。 EMrule 香港房屋委員會委員 2019/20 The Hong Kong Housing Authority Members 1 陳帆先生 2 唐智強先生 (運輸及房屋局局長) (房屋署署長)(由 2019年10月21日開始) ,英文用 The Honourable Frank CHAN Fan Mr Donald TONG Chi-keung 主席 (Secretary for Transport and Housing) 副主席 (Director of Housing) (from 21.10.2019) Chairman Vice-Chairman 委員Members 許美嫦女士 黃遠輝先生 蔡海偉先生 3 Ms Tennessy HUI Mei-sheung 4 Mr Stanley WONG Yuen-fai Mr CHUA Hoi-wai 蘇晴女士 張達棠先生 盧偉國議員 5 Ms SO Ching 6 Mr CHEUNG Tat-tong Dr the Honourable ENrule LO Wai-kwok 雷紹麟先生 張國鈞議員 郭偉强議員 7 Mr Alan LUI Siu-lun The Honourable Horace The Honourable CHEUNG Kwok-kwan KWOK Wai-keung 郭榮鏗議員 李國麟議員 柯創盛議員 The Honourable 8 Professor the Honourable 9 The Honourable Dennis KWOK Wing-hang Joseph LEE Kok-long Wilson OR Chong- 。 shing 陳家樂教授 彭韻僖女士 鄭慧恩女士 10 Professor CHAN Ka-lok 11 Ms Melissa Kaye PANG 12 Miss Vena CHENG Wei-yan 盧麗華博士 邵家輝議員 尹兆堅議員 13 Dr Miranda LOU Lai-wah The Honourable SHIU Ka-fai The Honourable Andrew WAN Siu-kin 陳志球博士 陳旭明先生 黃碧如女士 14 Dr Johnnie Casire 15 Mr Raymond CHAN Yuk- 16 Ms Cleresa WONG CHAN Chi-kau ming Pie-yue 陳正思女士 招國偉先生 麥萃才博士 17 Ms Cissy CHAN Ching-sze 18 Mr Anthony CHIU Kwok-wai 19 Dr Billy MAK Sui- choi 劉振江先生 陳婉珊女士 20 Mr LAU Chun-kong Ms Clara CHAN Yuen-shan 財經事務及庫務局常任秘書長(庫務) 地政總署署長 21 (財經事務及庫務局副秘書長(庫務)(2) 22 (地政總署副署長(一般事務) 黎志華先生或財經事務及庫務局首席助 陳佩儀女士或地政總署副署長 理秘書長(庫務)(管理會計)候補) (專業事務)候補) Permanent Secretary for Financial Director of Lands Services and the Treasury -

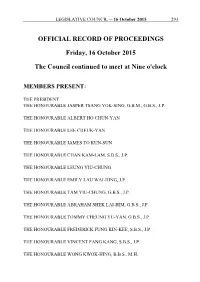

OFFICIAL RECORD of PROCEEDINGS Friday, 16 October

LEGISLATIVE COUNCIL ─ 16 October 2015 293 OFFICIAL RECORD OF PROCEEDINGS Friday, 16 October 2015 The Council continued to meet at Nine o'clock MEMBERS PRESENT: THE PRESIDENT THE HONOURABLE JASPER TSANG YOK-SING, G.B.M., G.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE ALBERT HO CHUN-YAN THE HONOURABLE LEE CHEUK-YAN THE HONOURABLE JAMES TO KUN-SUN THE HONOURABLE CHAN KAM-LAM, S.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE LEUNG YIU-CHUNG THE HONOURABLE EMILY LAU WAI-HING, J.P. THE HONOURABLE TAM YIU-CHUNG, G.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE ABRAHAM SHEK LAI-HIM, G.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE TOMMY CHEUNG YU-YAN, G.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE FREDERICK FUNG KIN-KEE, S.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE VINCENT FANG KANG, S.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE WONG KWOK-HING, B.B.S., M.H. 294 LEGISLATIVE COUNCIL ─ 16 October 2015 PROF THE HONOURABLE JOSEPH LEE KOK-LONG, S.B.S., J.P., Ph.D., R.N. THE HONOURABLE JEFFREY LAM KIN-FUNG, G.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE ANDREW LEUNG KWAN-YUEN, G.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE WONG TING-KWONG, S.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE CYD HO SAU-LAN, J.P. THE HONOURABLE STARRY LEE WAI-KING, J.P. DR THE HONOURABLE LAM TAI-FAI, S.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE CHAN HAK-KAN, J.P. THE HONOURABLE CHAN KIN-POR, B.B.S., J.P. DR THE HONOURABLE PRISCILLA LEUNG MEI-FUN, S.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE CHEUNG KWOK-CHE THE HONOURABLE WONG KWOK-KIN, S.B.S. -

會董名錄- List of the Chamber's Committee Members

會董名錄 List of the Chamber's Committee Members 第45屆首長 Office-bearers of the 45th Term of Office 會 長 Chairman 霍震寰 Mr Ian FOK Chun-wan, SBS, JP 副 會 長 Vice-chairmen 林廣兆 胡經昌 蔡冠深 張成雄 Mr LAM Kwong-siu, Mr Henry WU Dr Jonathan CHOI Mr CHEUNG Sing-hung SBS King-cheong, BBS, JP Koon-shum, BBS, JP 楊 釗 方文雄 陳幼南 林銘森 Dr Charles YEUNG, Mr David FONG Dr Ian CHAN Mr LAM Ming-sum SBS, JP Man-hung Yau-nam 主會要董會名務錄回 L顧ist oRfe tvhie wC hoaf mthbee Cr'hsa Cmobmemr'sit tMeea jMore Emvbeenrts 9 永遠榮譽會長 Life Honorary Chairmen 曾憲梓 陳有慶 Dr the Hon TSANG Dr Robin CHAN Hin-chi, GBM Yau-hing, GBS, LLD, JP 孫城曾 古勝祥 何世柱 黃宜弘 Mr SUN Sheng-tsang Mr Daniel KOO Mr HO Sai-chu, GBS, Dr the Hon Philip Y Shing-cheong JP WONG, GBS 張永珍 翁錦通 王敏剛 鄧 焜 Dr Alice Y T CHENG, Mr YUNG Kum-tung Mr Peter M K WONG, Mr TANG Kwan, SBS GBS, CGCROPSKS BBS, JP 10 香港中華總商會 The Chinese General Chamber of Commerce Annual Report 2007 年報 常務會董 黃守正 劉宇新 李祖澤 黃士心 朱蓮芬 曾智明 許智明 黃英豪 余國春 馬忠禮 梁海明 葉成慶 羅富昌 林銘森(至20.9.07) 鄧楊詠曼 伍威全 范佐華 陳 斌 司徒源傑 于善基 高敏堅 何志佳 施展熊 楊孫西(香江國際有限公司代表) 袁 武(招商局集團有限公司代表) 伍步剛(永隆銀行有限公司代表) 劉鐵成(東方石油有限公司代表) 李國雄(新光酒樓(有限公司)代表) 林廣明(中國銀行(香港)有限公司代表) 胡國祥(維京印刷有限公司代表) 葉志光(精棉發展有限公司代表) 葉樹林(能記有限公司代表) 梁偉浩(得利鐘錶製品廠有限公司代表) 莊學山(中南鐘錶有限公司代表) 李德麟(大唐金融集團有限公司代表) 李 歡(南北行公所代表) 王遼平(香港中國企業協會代表) 李宗德(香港中華出入口商會代表) 馬介璋(香港潮州商會有限公司代表) 盧文端(旅港福建商會代表)(5.1.07就任) 余文聰(旅港福建商會代表)(5.1.07退任) Standing Committee Members WONG Sau-ching LAU Yue-sun LEE Cho-jat Jackie WONG See-sum CHU Lien-fan Ricky TSANG Chi-ming HUI Ching-ming Kennedy WONG Ying-ho YU Kwok-chun Lawrence MA Chung-lai Raymond LEUNG Hai-ming IP Shing-hing LO Foo-cheung LAM Ming-sum (up to 19.9.07) Sophia DAN YANG Wing-man Wilson WU Wai-tsuen Vincent FAN Chor-wah David CHAN Pun SZETO Yuen-kit Joseph YU Mickey KO Man-kin Nelson HO Chi-kai SZE Chin-hung Jose YU Sun-say (Rep H.K.I. -

Oasis 2011 PUI CHING MIDDLE SCHOOL

Oasis 2011 PUI CHING MIDDLE SCHOOL PUI CHING MIDDLE SCHOOL 20 Pui Ching Road, Homantin, Hong Kong. Tel: 2711 9222 Fax: 2711 3201 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of the copyright owner. First published Jan 2011 by PUI CHING MIDDLE SCHOOL Hong Kong. ISBN: 978-988-99247-9-9 Printed in Hong Kong by Chung Tai Printing & Hot Blocking Co. Dedication The collection is dedicated to God, the founders of the school, and the inspiring principals and teachers of Pui Ching, who seek to make the school the best cradle for nurturing talents and leaders of generations in the past now and the time to come. Foreword Dr. Yip Chee Tim It is indeed my pleasure to read all these wonderful pieces of literary works by our students. The articles, in one way or another, display the talent of the students of Pui Ching. They can write extremely well. I am deeply touched by their beautiful style of writing. Their skills in writing bring forth special effects to impress those who enjoy reading. I am much impressed. Good works speak for themselves. Yip Chee Tim Principal 4 January 2011 Words from the Editors Subsequent to the previous revised publication of Oasis , there comes the heartwarming applause from various sides. With the precious experience and generous comments, we are now very honored to present to the readers yet another issue of this continual series, with a compilation of our students’ creative expression of their perception towards life.