Chapter 4 Cholera

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cholera Transmission: the Host, Pathogen and Bacteriophage Dynamic

REVIEWS Cholera transmission: the host, pathogen and bacteriophage dynamic Eric J. Nelson*, Jason B. Harris‡§, J. Glenn Morris Jr||, Stephen B. Calderwood‡§ and Andrew Camilli* Abstract | Zimbabwe offers the most recent example of the tragedy that befalls a country and its people when cholera strikes. The 2008–2009 outbreak rapidly spread across every province and brought rates of mortality similar to those witnessed as a consequence of cholera infections a hundred years ago. In this Review we highlight the advances that will help to unravel how interactions between the host, the bacterial pathogen and the lytic bacteriophage might propel and quench cholera outbreaks in endemic settings and in emergent epidemic regions such as Zimbabwe. 15 O antigen Diarrhoeal diseases, including cholera, are the leading progenitor O1 El Tor strain . Although the O139 sero- The outermost, repeating cause of morbidity and the second most common cause group caused devastating outbreaks in the 1990s, the El oligosaccharide portion of LPS, of death among children under 5 years of age globally1,2. Tor strain remains the dominant strain globally11,16,17. which makes up the outer It is difficult to gauge the exact morbidity and mortality An extensive body of literature describes the patho- leaflet of the outer membrane of Gram-negative bacteria. of cholera because the surveillance systems in many physiology of cholera. In brief, pathogenic strains har- developing countries are rudimentary, and many coun- bour key virulence factors that include cholera toxin18 Cholera toxin tries are hesitant to report cholera cases to the WHO and toxin co-regulated pilus (TCP)19,20, a self-binding A protein toxin produced by because of the potential negative economic impact pilus that tethers bacterial cells together21, possibly V. -

Cholera Outbreak Caused by Drug Resistant Vibrio Cholerae Serogroup

Gupta et al. Antimicrobial Resistance and Infection Control (2016) 5:23 DOI 10.1186/s13756-016-0122-7 RESEARCH Open Access Cholera outbreak caused by drug resistant Vibrio cholerae serogroup O1 biotype ElTor serotype Ogawa in Nepal; a cross-sectional study Pappu Kumar Gupta1, Narayan Dutt Pant2*, Ramkrishna Bhandari3 and Padma Shrestha1 Abstract Background: Cholera is a major cause of mortality and morbidity in underdeveloped countries including Nepal. Recently drug resistance in Vibrio cholerae has become a serious problem mainly in developing countries. The main objectives of our study were to investigate the occurrence of Vibrio cholerae in stool samples from patients with watery diarrhea and to determine the antimicrobial susceptibility patterns of V. cholerae isolates. Methods: A total of 116 stool samples from patients suffering from watery diarrhea during July to December 2012 were obtained from outbreak areas from all over Nepal. Alkaline peptone water and thiosulphate citrate bile salt sucrose agar (TCBS) were used to isolate the Vibrio cholerae. The isolates were identified with the help of colony morphology, Gram’s staining, conventional biochemical testing, serotyping and biotyping. Antimicrobial susceptibility testing was performed by determining the minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) by agar dilution method. Results: Vibrio cholerae was isolated from 26.72 % of total samples. All isolated Vibrio cholerae were confirmed to be Vibrio cholerae serogoup O1 biotype El Tor and serotype Ogawa. All isolates were resistant to ampicillin and cotrimoxazole. Twenty nine isolates were resistant toward two different classes of antibiotics, one strain was resistant to three different classes of antibiotics and one strain was resistant to four different classes of antibiotics. -

Cholera, Migration, and Global Health – a Critical Review

Int J Travel Med Glob Health. 2018 Sep;6(3):92-99 doi 10.15171/ijtmgh.2018.19 J http://ijtmgh.com IInternationalTMGH Journal of Travel Medicine and Global Health Review Article Open Access Cholera, Migration, and Global Health – A Critical Review Niyi Awofeso1*, Kefah Aldabk1 1Hamdan Bin Mohammed Smart University, Dubai, UAE Corresponding Author: Niyi Awofeso, PhD, Professor, Hamdan Bin Mohammed Smart University, Dubai, UAE. Tel: +97-144241018, Email: [email protected] Received February 1, 2018; Accepted April 7, 2018; Online Published September 25, 2018 Abstract Cholera is an acute diarrheal infection caused by the ingestion of food or water contaminated with the bacterium Vibrio cholerae. The causative agent of this disease was originally described by Filippo Pacini in 1854, and afterwards further analyzed by Robert Koch in 1884. It is estimated that each year there are 1.3 million to 4 million cases of cholera, and 21 000 to 143 000 deaths worldwide from the disease. Cholera remains a global threat to public health and an indicator of inequity and lack of social development. A global strategy on cholera control with a target to reduce cholera deaths by 90% was launched in 2017. Before 1817, cholera was confined to India’s Bay of Bengal. However, primarily following trade and migration between India and Europe, by the 1830s, cholera had spread internationally. The global spread of cholera was the driving force behind the first International Sanitary Conference in Paris, in 1851. The global health significance of cholera is underscored by its inclusion as one of four priority diseases in the 1969 and 2005 International Health Regulations. -

Vibrio Cholerae O1, O139)

Cholera! (Toxigenic Vibrio cholerae O1, O139) Note: Only toxigenic strains of Vibrio cholerae serogroups O1 and O139 cause epidemics and are reportable as cholera. This guidance is intended for management of patients with toxigenic strains of V. cholerae serogroups O1 and O139 and early management (i.e., before laboratory confirmation is available) of patients with cholera-like illness returning from regions where cholera activity has been reported (e.g., travelers returning from Haiti or the Dominican Republic). For management of non-toxigenic strains of V. cholerae O1 and O139, toxigenic strains of other V. cholerae serogroups (e.g. O75 and O141), and other Vibrio species, refer to the guidance for vibriosis. PROTOCOL CHECKLIST Enter available information into Merlin within 24 hours of notification Review background on disease, case definition, laboratory testing (section 2, 3, and 4) Contact provider (section 5) Confirm diagnosis Obtain available demographic and clinical information Determine what information was provided to the patient Ensure collection and submission of appropriate specimens (section 4) Interview patient(s) (section 5) Review disease facts (section 2) Description of illness Modes of transmission Ask about exposure to relevant risk factors (section 5) Travel to an area affected by cholera Exposure to untreated water sources Exposure to raw shellfish or undercooked seafood Consumption of food imported from an area affected by cholera Pre-existing conditions Identify any similar cases of illness among contacts Determine -

Transition of Drug Susceptibilities of Vibrio Cholerae O1 in Lao People’S Democratic Republic

DRUG SUSCEPTIBILITIES OF VIBRIO CHOLERAE O1 TRANSITION OF DRUG SUSCEPTIBILITIES OF VIBRIO CHOLERAE O1 IN LAO PEOPLE’S DEMOCRATIC REPUBLIC Bounnanh Phantouamath1, Noikaseumsy Sithivong1, Lay Sisavath1, Khamphyeu Munnalath1, Chomlasak Khampheng1, Sithat Insisiengmay1, Naomi Higa2, Shige Kakinohana2 and Masaaki Iwanaga2 1Center for Laboratory and Epidemiology, Ministry of Health, Vientiane, Lao PDR; 2Department of Bacteriology, Faculty of Medicine, University of the Ryukyus, Okinawa, Japan Abstract. The changes of drug susceptibilities of Vibrio cholerae O1 isolated during the past 7 years (1993-1999) in Lao PDR were investigated. The most noteworthy finding was the appearance of polymyxin B sensitive El Tor vibrios. Until 1996, the susceptibilities were almost as expected and cholera disappeared in 1997. When a cholera outbreak resurfaced in 1998, the susceptibilities of isolated V. cholerae O1 against tetracycline, sulfamethoxazol-trimethoprim, chloramphenicol and polymyxin B were quite different from those of previously isolated organ- isms. Minimum inhibitory concentrations (MICs) of tetracycline and chloramphenicol against the isolates in 1998 were about 16 times higher than those against the previous isolates, and the MICs of sulfamethoxazol-trimethoprim were about 256 times higher than those against the previous isolates, (trimethoprim 32 µg/ml: sulfamethoxazol 608 µg/ml). Eleven percent of the isolates (11/99) were as sensitive to polymyxin B as the classic cholera vibrios (MIC < 2 µg/ ml). In 1999, the susceptibility pattern was almost the same as that in 1998 except for polymyxin B to which 58% of the isolates (21/36) became sensitive. INTRODUCTION shown to shorten the duration to fewer days (Hischhorn et al, 1974). Since shortening of Vibrio cholerae Ol, the causative agent the symptomatic period is a positive merit of of cholera, are usually sensitive to therapeutic the antimicrobial treatment, the drug sensitiv- antimicrobials (Higa et al, 1995). -

The Columbian Exchange: a History of Disease, Food, and Ideas

Journal of Economic Perspectives—Volume 24, Number 2—Spring 2010—Pages 163–188 The Columbian Exchange: A History of Disease, Food, and Ideas Nathan Nunn and Nancy Qian hhee CColumbianolumbian ExchangeExchange refersrefers toto thethe exchangeexchange ofof diseases,diseases, ideas,ideas, foodfood ccrops,rops, aandnd populationspopulations betweenbetween thethe NewNew WorldWorld andand thethe OldOld WWorldorld T ffollowingollowing thethe voyagevoyage ttoo tthehe AAmericasmericas bbyy ChristoChristo ppherher CColumbusolumbus inin 1492.1492. TThehe OldOld WWorld—byorld—by wwhichhich wwee mmeanean nnotot jjustust EEurope,urope, bbutut tthehe eentirentire EEasternastern HHemisphere—gainedemisphere—gained fromfrom tthehe CColumbianolumbian EExchangexchange iinn a nnumberumber ooff wways.ays. DDiscov-iscov- eeriesries ooff nnewew ssuppliesupplies ofof metalsmetals areare perhapsperhaps thethe bestbest kknown.nown. BButut thethe OldOld WWorldorld aalsolso ggainedained newnew staplestaple ccrops,rops, ssuchuch asas potatoes,potatoes, sweetsweet potatoes,potatoes, maize,maize, andand cassava.cassava. LessLess ccalorie-intensivealorie-intensive ffoods,oods, suchsuch asas tomatoes,tomatoes, chilichili peppers,peppers, cacao,cacao, peanuts,peanuts, andand pineap-pineap- pplesles wwereere aalsolso iintroduced,ntroduced, andand areare nownow culinaryculinary centerpiecescenterpieces inin manymany OldOld WorldWorld ccountries,ountries, namelynamely IItaly,taly, GGreece,reece, andand otherother MediterraneanMediterranean countriescountries (tomatoes),(tomatoes), -

Enteric Infections Due to Campylobacter, Yersinia, Salmonella, and Shigella*

Bulletin of the World Health Organization, 58 (4): 519-537 (1980) Enteric infections due to Campylobacter, Yersinia, Salmonella, and Shigella* WHO SCIENTIFIC WORKING GROUP1 This report reviews the available information on the clinical features, pathogenesis, bacteriology, and epidemiology ofCampylobacter jejuni and Yersinia enterocolitica, both of which have recently been recognized as important causes of enteric infection. In the fields of salmonellosis and shigellosis, important new epidemiological and relatedfindings that have implications for the control of these infections are described. Priority research activities in each ofthese areas are outlined. Of the organisms discussed in this article, Campylobacter jejuni and Yersinia entero- colitica have only recently been recognized as important causes of enteric infection, and accordingly the available knowledge on these pathogens is reviewed in full. In the better- known fields of salmonellosis (including typhoid fever) and shigellosis, the review is limited to new and important information that has implications for their control.! REVIEW OF RECENT KNOWLEDGE Campylobacterjejuni In the last few years, C.jejuni (previously called 'related vibrios') has emerged as an important cause of acute diarrhoeal disease. Although this organism was suspected of being a cause ofacute enteritis in man as early as 1954, it was not until 1972, in Belgium, that it was first shown to be a relatively common cause of diarrhoea. Since then, workers in Australia, Canada, Netherlands, Sweden, United Kingdom, and the United States of America have reported its isolation from 5-14% of diarrhoea cases and less than 1 % of asymptomatic persons. Most of the information given below is based on conclusions drawn from these studies in developed countries. -

Bacterial Foodborne and Diarrheal Disease National Case Surveillance

Bacterial Foodborne and Diarrheal Disease National Case Surveillance Annual Report, 2003 Enteric Diseases Epidemiology Branch Division of Foodborne, Bacterial and Mycotic Diseases National Center for Zoonotic, Vectorborne and Enteric Diseases Centers for Disease Control and Prevention The Bacterial Foodborne and Diarrheal Disease National Case Surveillance is published by the Enteric Diseases Epidemiology Branch, Division of Foodborne, Bacterial and Mycotic Diseases, National Center for Zoonotic, Vectorborne and Enteric Diseases, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta, GA 30333 SUGGESTED CITATION Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Bacterial Foodborne and Diarrheal Disease National Case Surveillance. Annual Report, 2003. Atlanta Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2005: pg. Nos - 2 - Contents Executive Summary……………………………………………………………………………… - 4- Expanded Surveillance Summaries of Selected Pathogens and Diseases, 2003………………… -10- Botulism…………………………………………………………………………………. -10- Non-O157 Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli………………………………………-18- Salmonella………………………………………………………………………………...-22- Shigella……………………………………………………………………………………-28- Vibrio……………………………………………………………………………………...-33- Surveillance Data Sources and Background……………………………………………………... -40- National Notifiable Diseases Surveillance System and the National Electronic Telecommunications System for Surveillance…………………………………………… -40- Public Health Laboratory Information System…………………………………………... -41- Limitations common to NETSS and PHLIS…………………………………………….. -

Gonorrhea Also Called the "Clap" Or "Drip," Gonorrhea Is a Contagious Disease Transmitted Most Often Through Sexual Contact with an Infected Person

Gonorrhea Also called the "clap" or "drip," gonorrhea is a contagious disease transmitted most often through sexual contact with an infected person. Gonorrhea may also be spread by contact with infected bodily fluids, so that a mother could pass on the infection to her newborn during childbirth. Both men and women can get gonorrhea. The infection is easily spread and occurs most often in people who have many sex partners. What Causes Gonorrhea? Gonorrhea is caused by Neisseria gonorrhoeae, a bacterium that can grow and multiply easily in mucus membranes of the body. Gonorrhea bacteria can grow in the warm, moist areas of the reproductive tract, including the cervix (opening to the womb), uterus (womb), and fallopian tubes (egg canals) in women, and in the urethra (the tube that carries urine from the bladder to outside the body) in women and men. The bacteria can also grow in the mouth, throat, and anus. Gonorrhea symptoms in women ● Greenish yellow or whitish discharge from the vagina ● Lower abdominal or pelvic pain ● Burning when urinating ● Conjunctivitis (red, itchy eyes) ● Bleeding between periods ● Spotting after intercourse ● Swelling of the vulva (vulvitis) Gonorrhea symptoms in men ● Greenish yellow or whitish discharge from the penis ● Burning when urinating ● Burning in the throat (due to oral sex) ● Painful or swollen testicles ● Swollen glands in the throat (due to oral sex) In men, symptoms usually appear two to 14 days after infection. How Is Gonorrhea Treated? To cure a gonorrhea infection, your doctor will give you either an oral or injectable antibiotic. Your partner should also be treated at the same time to prevent reinfection and further spread of the disease. -

Influence of Environmental Conditions on Fatty Acid-Induced Changes in Vibrio Cholerae Persistence and Pathogenicity

University of Tennessee at Chattanooga UTC Scholar Student Research, Creative Works, and Honors Theses Publications 5-2019 Influence of environmental conditions on fatty acid-induced changes in Vibrio cholerae persistence and pathogenicity Abigail Doyle University of Tennessee at Chattanooga, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholar.utc.edu/honors-theses Part of the Environmental Sciences Commons Recommended Citation Doyle, Abigail, "Influence of environmental conditions on fatty acid-induced changes in Vibrio cholerae persistence and pathogenicity" (2019). Honors Theses. This Theses is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Research, Creative Works, and Publications at UTC Scholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of UTC Scholar. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Influence of environmental conditions on fatty acid-induced changes in Vibrio cholerae persistence and pathogenicity Abigail Lea Doyle Departmental Honors Thesis The University of Tennessee at Chattanooga Department of Civil and Chemical Engineering Examination Date: 08 April 2019 Bradley J. Harris, Ph.D. David Giles, Ph.D. Assistant Professor of Civil and Chemical Assistant Professor of Biology, Geology and Engineering Environmental Science Thesis Director Department Examiner ABSTRACT Vibrio cholerae, a Gram-negative bacterium, is responsible for the acute intestinal infection known as cholera. This illness is due in part to V. cholerae’s ability to sense and adapt to changing environments as it is ingested into the human body from brackish environments. It was shown in recent studies that this bacteria has the ability to uptake exogenous fatty acids, resulting in changes to V. -

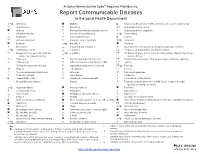

Report Communicable Diseases to the Local Health Department

Arizona Administrative Code Requires Providers to: Report Communicable Diseases to the Local Health Department *O Amebiasis Glanders O Respiratory disease in a health care institution or correctional facility Anaplasmosis Gonorrhea * Rubella (German measles) Anthrax Haemophilus influenzae, invasive disease Rubella syndrome, congenital Arboviral infection Hansen’s disease (Leprosy) *O Salmonellosis Babesiosis Hantavirus infection O Scabies Basidiobolomycosis Hemolytic uremic syndrome *O Shigellosis Botulism *O Hepatitis A Smallpox Brucellosis Hepatitis B and Hepatitis D Spotted fever rickettsiosis (e.g., Rocky Mountain spotted fever) *O Campylobacteriosis Hepatitis C Streptococcal group A infection, invasive disease Chagas infection and related disease *O Hepatitis E Streptococcal group B infection in an infant younger than 90 days of age, (American trypanosomiasis) invasive disease Chancroid HIV infection and related disease Streptococcus pneumoniae infection (pneumococcal invasive disease) Chikungunya Influenza-associated mortality in a child 1 Syphilis Chlamydia trachomatis infection Legionellosis (Legionnaires’ disease) *O Taeniasis * Cholera Leptospirosis Tetanus Coccidioidomycosis (Valley Fever) Listeriosis Toxic shock syndrome Colorado tick fever Lyme disease Trichinosis O Conjunctivitis, acute Lymphocytic choriomeningitis Tuberculosis, active disease Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease Malaria Tuberculosis latent infection in a child 5 years of age or younger (positive screening test result) *O Cryptosporidiosis -

Global Status of Tetracycline Resistance Among Clinical Isolates of Vibrio Cholerae: a Systematic Review and Meta‑Analysis Mohammad Hossein Ahmadi*

Ahmadi Antimicrob Resist Infect Control (2021) 10:115 https://doi.org/10.1186/s13756-021-00985-w RESEARCH Open Access Global status of tetracycline resistance among clinical isolates of Vibrio cholerae: a systematic review and meta-analysis Mohammad Hossein Ahmadi* Abstract Background: There has been an increasing resistance rate to tetracyclines, the frst line treatment for cholera disease caused by V. cholera strains, worldwide. The aim of the present study was to determine the global status of resistance to this class of antibiotic among V. cholera isolates. Methods: For the study, electronic databases were searched using the appropriate keywords including: ‘Vibrio’, ‘chol- era’, ‘Vibrio cholerae’, ‘V. cholerae’, ‘resistance’, ‘antibiotic resistance’, ‘antibiotic susceptibility’, ‘antimicrobial resistance’, ‘anti- microbial susceptibility’, ‘tetracycline’, and ‘doxycycline’. Finally, after some exclusion, 52 studies from diferent countries were selected and included in the study and meta-analysis was performed on the collected data. Results: The average resistance rate for serogroup O1 to tetracycline and doxycycline was 50% and 28%, respectively (95% CI). A high level of heterogeneity (I2 > 50%, p-value < 0.05) was observed in the studies representing resistance to tetracycline and doxycycline in O1 and non-O1, non-O139 serogroups. The Begg’s tests did not indicate the publica- tion bias (p-value > 0.05). However, the Egger’s tests showed some evidence of publication bias in the studies con- ducted on serogroup O1. Conclusions: The results of the present study show that the overall resistance to tetracyclines is relatively high and prevalent among V. cholerae isolates, throughout the world. This highlights the necessity of performing standard antimicrobial susceptibility testing prior to treatment choice along with monitoring and management of antibiotic resistance patterns of V.