Downloaded from Manchesterhive.Com at 09/26/2021 01:28:36AM Via Free Access 184 Horseracing and the British, 1919–39

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Acland Tony Freelance Research Consultant Southampton Matrix

Acland Tony Freelance Research Consultant Southampton Matrix Government Office for the South Alderman Angela DTI Team Leader (Hampshire & Isle of Wight) East, Guildford Southampton Focus Alford Lynne Director of Care SCA Community Care Services, Southampton Southampton Matrix Allan Kevin Manager Connexions, Southampton Southampton Matrix Almeida Tony Southampton Matrix Antrobus Tom Director Wessex Property Services, Eastleigh Southampton Matrix Arnold Elaine Regional Community Manager - South West Barclays PLC, Poole Exeter Focus Ash Jo Chief Executive Southampton Voluntary Services, Southampton Southampton Matrix Askham Tony Partner Bond Pearce, Southampton Southampton Matrix Aspinall Heather Chief Executive Rose Road Association, Southampton Southampton Matrix Atwill Dave Head of Public Relations New Forest District Council, Lyndhurst Southampton Matrix Bahra Harinder Change Management Consultancy -, Kenilworth Bahra Harinder Change Management Consultancy -, Kenilworth Southampton Matrix Baker Alan Southampton Matrix Ball Christine Southampton Matrix Barnes Di Team Leader Southampton Voluntary Services, Southampton Southampton Matrix Barnett Richard Associate Dean (External Development) Southampton Solent University -, Southampton Southampton Matrix Barnfield Nigel Basingstoke Focus Barritt Richard Chief Executive Mind Southampton and the New Forest, Southampton Southampton Matrix Bartrip Gilly Head of Sector Skills and Adult Learning South East England Development Agency, Guildford Southampton Matrix Bassom Mark Southampton Matrix Baxter -

2013/A/16 New Companies Registered Between 19-Apr-2013 and 25-Apr-2013

ISSUE ID: 2013/A/16 NEW COMPANIES REGISTERED BETWEEN 19-APR-2013 AND 25-APR-2013 CRO GAZETTE, FRIDAY, 26th April 2013 3 NEW COMPANIES REGISTERED BETWEEN 19-APR-2013 AND 25-APR-2013 Company Company Date Of Company Company Date Of Number Name Registration Number Name Registration 526433 BALLYCOTTON FISHERMANS ASSOCIATION 19/04/2013 526498 MPI PICTURES LIMITED 22/04/2013 LIMITED 526499 KMS INVESTMENTS LIMITED 22/04/2013 526434 TRANSFORM VENTURES LIMITED 19/04/2013 526500 DB O TUAIRISC 22/04/2013 526435 FINBUR PLANT LIMITED 19/04/2013 526501 HYSON LIMITED 22/04/2013 526436 ABK DRINKS LIMITED 19/04/2013 526502 ELD VISION LIMITED 22/04/2013 526437 RYSTON VENTURES LIMITED 19/04/2013 526503 BALROWAN LIMITED 22/04/2013 526438 ICAT LIMITED 19/04/2013 526504 AMBER SOUTHERN EUROPEAN EQUITY LIMITED 22/04/2013 526439 GLEN VENTURES LIMITED 19/04/2013 526505 ION TRADING TECHNOLOGIES LIMITED 22/04/2013 526440 DUBLIN INK SOCIAL CLUB LIMITED 19/04/2013 526506 WESTOWN FARM LIMITED 22/04/2013 526441 THE VISIT PRODUCTIONS LIMITED 19/04/2013 526507 TULLORE FARM LIMITED 22/04/2013 526442 JAMES E. DWYER LIMITED 19/04/2013 526508 ACCOMMODATIONS PLUS EUROPE LIMITED 22/04/2013 526443 HGPOS LIMITED 19/04/2013 526509 MAHARLIKA SOFTWARE SOLUTIONS LIMITED 22/04/2013 526444 DAY BY DAY SUPPORT SERVICES LIMITED 19/04/2013 526510 TOLEA HOLDINGS LIMITED 22/04/2013 526445 CHARLIE’S CHILDCARE LIMITED 19/04/2013 526511 A Z LOCUMS LIMITED 22/04/2013 526446 BODEN PROJECTS LIMITED 19/04/2013 526512 KAILI LIMITED 22/04/2013 526447 ILLUMINATION SOLUTIONS AUDRIUS & 19/04/2013 526513 SUNBEAM BINGO LIMITED 22/04/2013 ALEKSANDR LIMITED 526514 SAITC LIMITED 22/04/2013 526448 CARRIGBEL CONSTRUCTION LIMITED 19/04/2013 526515 CEANN AN DAIMH LIMITED 22/04/2013 526449 FAB HAIR STUDIO LIMITED 19/04/2013 526516 JOE KELLY IT CONSULTING LIMITED 22/04/2013 526450 MASSI-MAN LIMITED 19/04/2013 526517 T & L MANNION FARM LIMITED 22/04/2013 526451 ERGZAHER HOLDINGS LIMITED 19/04/2013 526518 P. -

NP 2013.Docx

LISTE INTERNATIONALE DES NOMS PROTÉGÉS (également disponible sur notre Site Internet : www.IFHAonline.org) INTERNATIONAL LIST OF PROTECTED NAMES (also available on our Web site : www.IFHAonline.org) Fédération Internationale des Autorités Hippiques de Courses au Galop International Federation of Horseracing Authorities 15/04/13 46 place Abel Gance, 92100 Boulogne, France Tel : + 33 1 49 10 20 15 ; Fax : + 33 1 47 61 93 32 E-mail : [email protected] Internet : www.IFHAonline.org La liste des Noms Protégés comprend les noms : The list of Protected Names includes the names of : F Avant 1996, des chevaux qui ont une renommée F Prior 1996, the horses who are internationally internationale, soit comme principaux renowned, either as main stallions and reproducteurs ou comme champions en courses broodmares or as champions in racing (flat or (en plat et en obstacles), jump) F de 1996 à 2004, des gagnants des neuf grandes F from 1996 to 2004, the winners of the nine épreuves internationales suivantes : following international races : Gran Premio Carlos Pellegrini, Grande Premio Brazil (Amérique du Sud/South America) Japan Cup, Melbourne Cup (Asie/Asia) Prix de l’Arc de Triomphe, King George VI and Queen Elizabeth Stakes, Queen Elizabeth II Stakes (Europe/Europa) Breeders’ Cup Classic, Breeders’ Cup Turf (Amérique du Nord/North America) F à partir de 2005, des gagnants des onze grandes F since 2005, the winners of the eleven famous épreuves internationales suivantes : following international races : Gran Premio Carlos Pellegrini, Grande Premio Brazil (Amérique du Sud/South America) Cox Plate (2005), Melbourne Cup (à partir de 2006 / from 2006 onwards), Dubai World Cup, Hong Kong Cup, Japan Cup (Asie/Asia) Prix de l’Arc de Triomphe, King George VI and Queen Elizabeth Stakes, Irish Champion (Europe/Europa) Breeders’ Cup Classic, Breeders’ Cup Turf (Amérique du Nord/North America) F des principaux reproducteurs, inscrits à la F the main stallions and broodmares, registered demande du Comité International des Stud on request of the International Stud Book Books. -

Kahlil Gibran a Tear and a Smile (1950)

“perplexity is the beginning of knowledge…” Kahlil Gibran A Tear and A Smile (1950) STYLIN’! SAMBA JOY VERSUS STRUCTURAL PRECISION THE SOCCER CASE STUDIES OF BRAZIL AND GERMANY Dissertation Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for The Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Susan P. Milby, M.A. * * * * * The Ohio State University 2006 Dissertation Committee: Approved by Professor Melvin Adelman, Adviser Professor William J. Morgan Professor Sarah Fields _______________________________ Adviser College of Education Graduate Program Copyright by Susan P. Milby 2006 ABSTRACT Soccer playing style has not been addressed in detail in the academic literature, as playing style has often been dismissed as the aesthetic element of the game. Brief mention of playing style is considered when discussing national identity and gender. Through a literature research methodology and detailed study of game situations, this dissertation addresses a definitive definition of playing style and details the cultural elements that influence it. A case study analysis of German and Brazilian soccer exemplifies how cultural elements shape, influence, and intersect with playing style. Eight signature elements of playing style are determined: tactics, technique, body image, concept of soccer, values, tradition, ecological and a miscellaneous category. Each of these elements is then extrapolated for Germany and Brazil, setting up a comparative binary. Literature analysis further reinforces this contrasting comparison. Both history of the country and the sport history of the country are necessary determinants when considering style, as style must be historically situated when being discussed in order to avoid stereotypification. Historic time lines of significant German and Brazilian style changes are determined and interpretated. -

FIVE DIAMONDS Barn 2 Hip No. 1

Consigned by Three Chimneys Sales, Agent Barn Hip No. 2 FIVE DIAMONDS 1 Dark Bay or Brown Mare; foaled 2006 Seattle Slew A.P. Indy............................ Weekend Surprise Flatter................................ Mr. Prospector Praise................................ Wild Applause FIVE DIAMONDS Cyane Smarten ............................ Smartaire Smart Jane........................ (1993) *Vaguely Noble Synclinal........................... Hippodamia By FLATTER (1999). Black-type-placed winner of $148,815, 3rd Washington Park H. [G2] (AP, $44,000). Sire of 4 crops of racing age, 243 foals, 178 starters, 11 black-type winners, 130 winners of 382 races and earning $8,482,994, including Tar Heel Mom ($472,192, Distaff H. [G2] (AQU, $90,000), etc.), Apart ($469,878, Super Derby [G2] (LAD, $300,000), etc.), Mad Flatter ($231,488, Spend a Buck H. [G3] (CRC, $59,520), etc.), Single Solution [G3] (4 wins, $185,039), Jack o' Lantern [G3] ($83,240). 1st dam SMART JANE, by Smarten. 3 wins at 3 and 4, $61,656. Dam of 7 registered foals, 7 of racing age, 7 to race, 5 winners, including-- FIVE DIAMONDS (f. by Flatter). Black-type winner, see record. Smart Tori (f. by Tenpins). 5 wins at 2 and 3, 2010, $109,321, 3rd Tri-State Futurity-R (CT, $7,159). 2nd dam SYNCLINAL, by *Vaguely Noble. Unraced. Half-sister to GLOBE, HOYA, Foamflower, Balance. Dam of 6 foals to race, 5 winners, including-- Taroz. Winner at 3 and 4, $26,640. Sent to Argentina. Dam of 2 winners, incl.-- TAP (f. by Mari's Book). 10 wins, 2 to 6, 172,990 pesos, in Argentina, Ocurrencia [G2], Venezuela [G2], Condesa [G3], General Lavalle [G3], Guillermo Paats [G3], Mexico [G3], General Francisco B. -

Streets Sackville Street Built on Brunswick Gardens 45 Named After

Streets http://www.pomeroyofportsmouth.uk/portsmouth-local-history.html Sackville Street Built on Brunswick Gardens 45 Named after Dukes of Bedford See Jervis Street 1839-1847 Sackville Street 94 1859-1964 91 St Vincent Street to 92 St James Road 1,42,59, 165,166 Split in two 1961 Compulsory purchase order Nos. 27-37 9 1918 Nos. 23 & 25 purchased for £495 95 1957 No. 18 and 20 purchased for £600 95 Sackville Street 1975-2008 Eldon Street to Astley Street 1 North Side South Side Old Old 1 2 9 20 Corn Exchange Melbourne Street 42 11 South Street 19 44 Red Lion West Street 58 The Willow Eldon Street Middle Street 60 21 62 21a Pure Drop Inn 25 Alton Arms 41 New New Stratford House The Brook Club Oldbury House Sirius Court Brunswick Street Eldon Court Peel Place 2000-2008 St James Road to Astley Street North Side South Side 1-2 pair 1998 PCC St Albans Road 1913 95 1915 St Alban’s Road to be numbered 95 1918-2006 26 St Anns Road to 8 Tower Road 1 1913 [19431] 9 houses in St Albans Road by T.L Norman 95 1913 [19509] 12 houses by H Durrant 95 1913 [19550] 12 houses by H Durrant 95 1914 [19921] 1 house in St Ann’s Road, 1 house in St Alban’s Road for W.G Keeping 95 1914 [19965] 7 houses in Tower Road & St Albans Road for W.G Keeping 95 1915 Renumbered 192 East Side West Side Streets http://www.pomeroyofportsmouth.uk/portsmouth-local-history.html 2 Melita 1-7unnamed terrace 4-26 unnamed terrace 1 St Cross 4 Doris House 3 Dorothy 6 Ivydene 9-19 unnamed terrace 8 Queensborough 11 Canford 10 Moreton House 13 Devonia 12 Limerick 15 The Haven 14 Rosedene 19 Floriana 16 Boscombe 18 Branksome 20 Heaton 22 Kiverton 24 Jesmond Dene 26 Inglenook St Andrew’s Buildings See Andrew’s Buildings St Andrew’s Road Named after St Andrew’s University (and Prof John Playfair) Part of St Peter’s Park Estate 1881 171 1885-2008 161 Elm Grove to 25 Montgomerie Road 1,5(16), 165,166 ?Caudieville 1937 [29923] 37 St Andrews Road convert to 2 flats by Bowerman Bros for Mr Bull 95 1939 Repair notice issued No. -

Appendix to Post Publication Changes

APPENDIX - Austria APPENDIX TO POST PUBLICATION CHANGES The races contained in this section reflect any amendments to races run in 2009 since the publication of the 2009 International Cataloguing Standards Book. AUSTRIA A Published as: Run in 2009 with the following modifications: Osterreichisches Galopperderby G1 Magna Austrian Derby 2009 G1 Born Wild Steher-Preis (LR) Grober Preis der RZB (LR) Internationaler Austria-Preis G3 Toto Trophy G3 Kincsem-Preis G2 Grober Preis der TEG G2 P Magna Racino Sprint (LR) WINWIN TRIFECTA JACKPOT Rennen (LR) Trial S. G2 Trial-Stakes 2009 G2 P E N D I X A-1 APPENDIX - Brazil BRAZIL Published as: Run in 2009 with the following modifications: Almirante Marques de Tamandaré G3 2400 S 2400 T Derby Club (L) - 3500 T 3500 S Dia da Justiça (L) - 1000 T 1100 S Diana (L) - 2000 T 2100 S Erasmo T. de Assumpção (L) - 1000 T 1100 S Euvaldo Lodi G3 - 1600 T 1600 S Francisco Eduardo de Paula Machado 2000 S G1 - 2000 T Frederico Lundgren G3 - 1600 T 1600 S Linneo de Paula Machado G3 - 2000 T 2000 S Mariano Procópio G3 - 1600 T 1600 S Natal (L) - 1800 T 1900 S Octávio Dupont (L) - 1600 T 1600 S Oswaldo Aranha G2 - 2400 T 2400 S Ricardo Xavier da Silveria (L) not run as a Listed race A-2 APPENDIX - Canada CANADA Published as: Run in 2009 with the following modifications: Ballerina S. G3, $100,000 $125,000 British Columbia Derby G3, $300,000 $275,000 British Columbia Oaks (L), $100,000 $125,000 Canadian Juvenile S. -

GOTHENBURG CHAMPIONSHIPS MAKE a Note in Your Diaries Sporting Vilette Charleroi Now

Agreements have been reached with Tamasu Butterfly Europa and Nittaku for the supply :./ .. ,iii.· I of table tennis equipment to the European Table Tennis Championships 1994. Butterfly will supply Butterfly Centrefold Rollaway tables, Butterfly Europa net and post sets, Butterfly umpires tables, scoring machines and surrounds. Nittaku will supply 3-star balls. Representatives of both companies were pleased to meet English Table Tennis Association's President, Johnny Leach in Gothenburg at the recent World Championships. The agreements with both companies involve the supply of all the required equipment for the European Championships, together with an undisclosed adoption fee. English Table Tennis Association's Chief Executive, Elaine Shaw, commented "we are looking forward to working with both companies and would like to thank them for their support." PAGE 2 ,-:;;..." The ETTA would like to thank the following companies for the support they give to Player of the Month English table tennis: TABLE TENNIS NEWS May/June 1993 - Issue 215 The official magazine of The English Table Tennis Association Third Floor, Queensbury House, Havelock Road, Hastings. TN34 1HF Tel: 0424 722525 Fax: 0424 422103 President J A Leach MBE Chairman A E Ransome Editor John F A Wood This month's choice is Ryan Savill from Essex, who leapt Editorial Office: from obscurity to take the Junior Open by storm, reaching the 5 The Brackens, semi finals, where he lost to Germany's Sascha Kostner Hemel Hempstead, ~l Herts. HP2 5JA Tel/Fax: 0442 244547 CHATTERBOX. On top of the world Advertisement Offices: Jim Beckley, Sports PR Nitt4ku POBox 8, Cheadle Hulme, Cheadle, Cheshire. -

Download Entire 2010 Book

INTERNATIONAL CATALOGUING STANDARDS and INTERNATIONAL STATISTICS 2010 Maintained by The International Grading and Race Planning Advisory Committee (IRPAC) Published by The Jockey Club Information Systems, Inc. in association with the International Federation of Horseracing Authorities The standards established by IRPAC have been approved by the Society of International Thoroughbred Auctioneers www.ifhaonline.org/standardsBook.asp TABLE OF CONTENTS Introductory Notes ........................................................................vii International Cataloguing Standards Committee ............................x International Grading and Race Planning Advisory Committee (IRPAC) ......................................................................................xi Society of International Thoroughbred Auctioneers....................xiii Black-Type Designators for North American Racing..................xvi TOBA/American Graded Stakes Committee ............................xviii International Rule for Assignment of Weight Penalties ..............xxi List of Abbreviations ..................................................................xxii Explanatory Notes ....................................................................xxiii Part I Argentina ................................................................................1-1 Australia ..................................................................................1-7 Brazil......................................................................................1-19 Canada ..................................................................................1-24 -

DORCIA Sidste Års 3-Årige HAVDE JEG DOG BARE HØRT EFTER Den

Dorcia får et ”mudderkys” af Carlos Lopez efter den imponerende sejr i Svenskt Derby sidste år. Hun var da trænet af Lennart Reuterskiöld Jr., men fortsætter nu karrieren hos Pia RaceTime Brandt i Frankrig. MAGA ZINE DORCIA Sidste års 3-årige HAVDE JEG DOG BARE HØRT EFTER Den dødsdømtes derbytips GALILEO Stadig Europas førende avlshingst VINZENZ VOGEL En lille dreng skal da ikke føle sig som konge VIDSTE DU DET? Historien om Isinglass DET SKAL VÆRE SJOVT - DET SKAL VÆRE EN HOBBY På besøg hos Stald Jupiter Af: Klaus Bustrup og Per Aagaard Bustrup Det var den RaceTime 29 østrigskfødte 03 hesteejer og DORCIA opdrætter, Fritz VINZENZ VOGEL MAGAZINE/2 Thurnstein von ”Dorcia - stjernen ”En lille dreng skal Aucktenhaler, 2. Årgang/2018 over dem alle,” er da ikke føle sig som der fik formidlet DET HANDLER OGSÅ OM MENNESKER overskriften på en en konge!” fik østrig- en kontrakt Galopløb drejer sig om galopheste. Om artikel i dette num- sfødte Vinzenz mellem en hvem, der kommer først i mål. Men galopløb mer. En gennem- Vogel at vide fra sin dansk træner handler også om mennesker. Om dem, der gang af sidste års træner efter sin før- skaber rammerne for galopløb. Og ikke kun og Vinzenz 3-årige, der i 2018 ste sejr. om galoptrænere- og jockeys. Men også om Vogel, så han skal ud og kæmpe engagerede amatørryttere. Om alle de unge kunne flytte til mod den etablerede Siden blev det til piger for hvem morgenridtet er altafgørende. Danmark. Her ældre elite. mange som både Om offervillige hesteejere og - opdrættere. blev Vinz bo- jockey og træner i Om hesteagenter. -

Aqha Financial Members Expires 31/7/2021

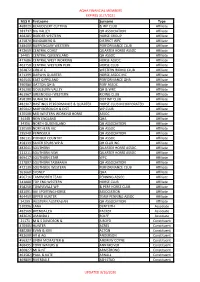

AQHA FINANCIAL MEMBERS EXPIRES 31/7/2021 M/S # Firstname Surname Type 468829 BEAUDESERT CUTTING & WP CLUB Affiliate 383737 BIG VALLEY QH ASSOCIATION Affiliate 468285 BORDER WESTERN HORSE GROUP Affiliate 475870 BUNDABERG & DISTRICT WPC Affiliate 348400 BURPENGARY WESTERN PERFORMANCE CLUB Affiliate 472659 CENTRAL COAST QUARTER HORSE ASSOC Affiliate 34405 CENTRAL QUEENSLAND QH ASSOC Affiliate 477686 CENTRAL WEST WORKING HORSE ASSOC. Affiliate 463750 CENTRAL WESTERN PERF. HORSE CLUB Affiliate 362872 CIRCLE C WESTERN RIDING CLUB Affiliate 471399 DARWIN QUARTER HORSE ASSOC INC Affiliate 464546 EAST GIPPSLAND PERFORMANCE QHA Affiliate 390980 GATTON QH & PERF ASSOC Affiliate 426298 GOULBURN VALLEY QH & WRC Affiliate 461967 GREENOUGH WESTERN RIDING CLUB Affiliate 458180 GUNALDA & DIST WP CLUB Affiliate 482307 HASTINGS PERFORMANCE & QUARTER HORSE CLUB INCORPORATED Affiliate 465042 MARYBOROUGH & DIST WP CLUB Affiliate 470508 MID WESTERN WORKING HORSE ASSOC Affiliate 34348 NEW ENGLAND QHA Affiliate 34356 NORTH QUEENSLAND QH ASSOCIATION Affiliate 130500 NORTHERN VIC QH ASSOC Affiliate 295940 PENINSULA QH ASSOCIATION Affiliate 186131 PIONEER COUNTRY QH ASSOC Affiliate 458339 SILVER SPURS WP & QH CLUB INC. Affiliate 482641 SOUTHERN QUARTER HORSE ASSOC. Affiliate 111211 SOUTHERN NSW QUARTER HORSE ASSOC Affiliate 469417 SOUTHERN STAR WPC Affiliate 117897 SOUTHERN TASMANIA QH ASSOCIATION Affiliate 472139 SOUTHSIDE WESTERN PERFORMANCE CLUB Affiliate 261660 SYDNEY QHA Affiliate 456716 TAMWORTH TEAM PENNING ASSOC. Affiliate 343880 TOP END WESTERN HORSE CLUB -

Portraits of Illustrious Personages of Great Britain : with Biographical

N v' iN V / j\ V / l\ V / f\ V / / v/ i\ N ' /''AC A X* .''I " I sO^I '-I .'>/ V*"/ C/V\C#\.aa,^ / X />\S a' a' A'>/ /vaa; S\s* v » ' ^ ' -- '-'S'' />vy a* w a^-ma/a ^S\S^7^z,'- «r • /\i •'•' 1 • .. /-^ i^aiAAu^AAki^AAaiXXu^AA .ij'.AA^ AAix^/-A«i.^.A«Ui-A..^ •. .^7\ . / N ,\ y~>xs / — n / T\'W/> /'A s \ s /L-M / x ,\ /-\ W'X H'IS .C/> /'Xk' Vrc V? /N ,\ / -\ N / ,\ ! ?f§ *5$ S\' /— \; v7^-( eluding Vohune. Portrait of Maria Theresa. \ ISI-.v" 23. LANZI'S HISTORY OF. PAINTING. VOL. 3, (which completes the Work.) With Portrait of Correijtjio. 24. MACHIAVELLI’S HISTORY OF FLORENCE, PRINCE, AND OTHER Works. /n/A Portrait. ^Vvo 1 25. SCHLEGEL'S LECTURES ON THE PHILOSOPHY OF LIFE 1 PHILOSOPHY 01' LANGUAGE, translated by A. J. W. Morrison. 26. LAMARTINE’S HISTORY OF THE GIRONDISTS. VOL. 2. Portrait of JDuMine Boland. 27. RANKE'S HISTORY OF THE POPES, TRANSLATED BY E. FOSTER. Vol. 1. Portrait of Julius II., after Raphael. 28. COXE'S MEMOIRS OF THE DUKE OF MARLBOROUGH, (to form 3 vols.) Vol. 1. With fine Portrait. Ax Atlas, containing 26 fine large Maps and Plans of Marlborough’s Campaigns, being f.ll n those published in the original edition at £12 12s. may now be had, in one volume, 4to. for 10s. Ud. 29. SHERIDAN'S DRAMATIC WORKS AND LIFE. Portrait. 30. COXE'S MEMOIRS OF MARLBOROUGH. VOL. 2. Portrait of the Duchess. 31. GOETHE'S AUTOBIOGRAPHY, 13 BOOKS.