Breeders and Owners

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

M.Taylor-West India Interest and Colonial Slavery in Parliament

1 The West India Interest and Colonial Slavery in Parliament, 1823-33 Michael Taylor Parliament, Politics, and People, 3 November Abstract: This paper considers the parliamentary fortunes of the British pro-slavery lobby – the West India Interest – between the advent of the anti-slavery campaign in early 1823 and the passage of the Slavery Abolition Act in August 1833. First, it explains the parliamentary strength of the West India Interest under the Tory ministries of the 1820s. Second, it examines the uncertainty of the first few years after Catholic Emancipation and under Earl Grey’s Whigs. Finally, it narrates the rapid and terminal decline of the parliamentary Interest as the result of Reform and the ultimate passage of the Slavery Abolition Act. In 1823, there were no political parties in Great Britain, at least not in the modern sense. Robert Jenkinson, the Earl of Liverpool, might have been the prime minister in a ‘Tory’ government, but there was no Tory Party. Indeed, Liverpool demanded only ‘a generally favourable disposition’ from his affiliated MPs and had even declared that he would ‘never attempt to interfere with the individual member’s right to vote as he may think consistent with his duty upon any particular question’. On the opposite benches were the Whigs, led by Charles, the Earl Grey, but there was no Whig Party either. Rather, the ‘Tories’ and the ‘Whigs’ were loose coalitions of politicians who shared generally similar attitudes. Put crudely, the Tories were the conservative friends of the Crown and the Church of England who glorified the memory of Pitt the Younger; the Whigs were the friends of trade, finance, and nonconformist religion, cautious advocates of parliamentary reform, and the political descendants of Pitt’s great rival, Charles James Fox. -

Greyhound Clubs Australia 2021/22 Group Race Calendar As Amended July 4, 2021

Greyhound Clubs Australia 2021/22 Group Race Calendar As amended July 4, 2021 Disclaimer: Greyhound Clubs Australia has published this version of the 2021/22 Group Race Calendar as a service to the greyhound racing industry. At the time of publishing, the information contained in the calendar was believed to be accurate and correct. The calendar has been published in good faith but Greyhound Clubs Australia does not accept any responsibility for any inaccuracies it may contain. Persons intent on nominating greyhounds for events within the calendar, or relying upon the calendar for any other use or purpose, are advised to confirm dates and other relevant information with the host organisations. Host Event Name Group/Listed Dates First prize Eligibility guide Status Brisbane GRC Brisbane Cup 1 July 1, 8 $250,000 Best 64 greyhounds 520m nominated plus reserves. Specific event order of entry conditions apply. Brisbane GRC Queensland 1 July 1, 8 $100,000 Best greyhounds Cup 710m nominated, plus reserves. RQ grading policy applies. Grafton GRC Grafton Listed July 7 $15,000 Open to maiden Maiden 407m (Heats June greyhounds. 28) GRNSW grading policy applies. Sandown GRC McKenna 2 July 1, 8 $40,000 Best greyhounds Memorial nominated plus 595m reserves. GRV grading policy applies. GWA Middle Listed July 2, 9 $19,950 Best greyhounds Mandurah Distance nominated plus Challenge reserves, based on provincial middle distance grade. RWWA grading policy applies. NSW GBOTA Peter Mosman 1 Event $75,000 Best female Wentworth Opal 520m postponed greyhounds Park – dates to nominated, plus be reserves, whelped determined. on or after March 1, 2019. -

Sac S "A:4.A4

SAC S "A:4.A4 4 t No. gS Winter 1957 Price 216 SHOWCASES and DISPLAY EQUIPMENT of good design and construction MUSEUM FITTERS CONSTITUTION HILL BIRMINGHAM I 9 ESTABLISHED I870 Distinguished Old & Modern Paintings ROLAND, BROWSE & DELBANCO 19 CORK STREET OLD BOND STREET LONDON W.1 THE LIBRARIES & ARTS (ART GALLERY &, TEMPLE NEWSAM HOUSE) SUB-COMMITTEE The l.ord Mavor Chairman Alderman A. Adamson Alderman Mrs. M. I'earce, J.P. Councillor iVIrs. A. M. M. Happ<il<l, XI.A. Alderman Mrs. W. Shut t Councillor T. W. Kirkby Alderman H. S. Vick, J.P. Councillor Mrs. L. Lyons Councillor St. John Binns Councillor Mrs. M. S. iMustill Councillor Mtw. G. Bray Councillor A. S. Pedley, D.F.C. Councillor R. I. Ellis Councillor J. T. V. Watson, LL.B. Co-opted .Members I.arly Martin Mr. W. T. Oliver THE LEEDS ART COLLECTIONS FUND Patroness H.R.H. 'I'he Princess Royal Pre.<ident The Rt. I-lon. the Earl of Halifax, K.G., O.M., G.C.S.I.,G.C.I.E. Vice-President The Rt. Hon. the Earl of Harewood Trustees Major Le G. G. W. Horton-Fawkes, O.B.E. Mr. W. Gilchrist Mr. C. S. Reddihough Connn 't tee Alderman A. Adamson Miss I'heo Moorrnan Mr. George Black Mr. W. T. Oliver Mr. D. D. Schofield Mr. H. P. Peacock Mr. David B. Ryott Mr. Martin Arnold (Hon. Treasureri Mrs. S. Gilchrist iHon.,Social Secretary'l .Ill Corrununications to he addressed lo Temple ~Veu'sarrt House, Leeds Subscriptions for the .Irts Calendar should be sent to: The Hon. -

Annual Veterinary Kennel Inspections Re-Homing Retired Greyhounds Independently

Vol 11 / No 17 23 August 2019 Fortnightly by Subscription calendar Annual Veterinary Kennel Inspections Re-homing Retired Greyhounds Independently SEAGLASS TIGER wins the Ladbrokes Gold Cup 2019 at Monmore for owner Evan Herbert and trainer Patrick Janssens (pictured with wife Cheryl (far left) and Photo: Joanne Till kennelhand Kelly Bakewell holding the winner). FOR ALL THE LATEST NEWS - WWW.GBGB.ORG.UK -VSSV^.).)VU;^P[[LY'NYL`OV\UKIVHYK'NINIZ[HɈHUK0UZ[HNYHTHUK-HJLIVVR CATEGORY ONE FINALS Date Distance Track Event Mon 26 Aug 500m Puppies Nottingham Puppy Classic Fri 06 Sep 575m Romford Coral Champion Stakes Fri 13 Sep 925m Romford Coral TV Trophy Thu 19 Sep 462m Yarmouth RPGTV East Anglian Derby Thu 26 Sep 480m British Bred Newcastle BGBF Northern Plate Fri 27 Sep 400m Puppies Romford Romford Puppy Cup Sat 05 Oct 714m Crayford Jay and Kay Coach Tours Kent St Leger Sun 06 Oct 480m Central Park Ladbrokes Kent Derby Mon 21 Oct 500m British Bred Nottingham BGBF/Nottingham British Breeders Stakes Weds 23 Oct 661m Doncaster SIS Yorkshire St Leger Sun 27 Oct 460m Henlow Henlow Derby Sat 02 Nov 540m Crayford Ladbrokes Gold Collar Sat 16 Nov 710m Perry Barr RPGTV St Leger Mon 18 Nov 500m Nottingham Eclipse Stakes Fri 06 Dec 575m Romford Coral Essex Vase 7XH'HF P%ULWLVK%UHG 6KHIÀHOG %*%)%ULWLVK%UHG'HUE\ Thu 19 Dec 515m Brighton & Hove Coral Olympic )XUWKHUFRPSHWLWLRQVWREHFRQÀUPHG$ERYHGDWHVPD\EHVXEMHFWWRFKDQJH ANNUAL VETERINARY KENNEL INSPECTIONS All Professional and Greyhound trainers are reminded to arrange for their Annual Veterinary Kennel Inspection to take place using the form that was enclosed with their 2019 licence cards, additional forms can be obtained from any Racing Office, from the GBGB office (0207 822 0927), or from the GBGB website. -

Equine Laminitis Managing Pasture to Reduce the Risk

Equine Laminitis Managing pasture to reduce the risk RIRDCnew ideas for rural Australia © 2010 Rural Industries Research and Development Corporation. All rights reserved. ISBN 978 1 74254 036 8 ISSN 1440-6845 Equine Laminitis - Managing pasture to reduce the risk Publication No. 10/063 Project No.PRJ-000526 The information contained in this publication is intended for general use to assist public knowledge and discussion and to help improve the development of sustainable regions. You must not rely on any information contained in this publication without taking specialist advice relevant to your particular circumstances. While reasonable care has been taken in preparing this publication to ensure that information is true and correct, the Commonwealth of Australia gives no assurance as to the accuracy of any information in this publication. The Commonwealth of Australia, the Rural Industries Research and Development Corporation (RIRDC), the authors or contributors expressly disclaim, to the maximum extent permitted by law, all responsibility and liability to any person, arising directly or indirectly from any act or omission, or for any consequences of any such act or omission, made in reliance on the contents of this publication, whether or not caused by any negligence on the part of the Commonwealth of Australia, RIRDC, the authors or contributors. The Commonwealth of Australia does not necessarily endorse the views in this publication. This publication is copyright. Apart from any use as permitted under the Copyright Act 1968, all other rights are reserved. However, wide dissemination is encouraged. Requests and inquiries concerning reproduction and rights should be addressed to the RIRDC Publications Manager on phone 02 6271 4165. -

On the Laws and Practice of Horse Racing

^^^g£SS/^^ GIFT OF FAIRMAN ROGERS. University of Pennsylvania Annenherg Rare Book and Manuscript Library ROUS ON RACING. Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2009 with funding from Lyrasis IVIembers and Sloan Foundation http://www.archive.org/details/onlawspracticeOOrous ON THE LAWS AND PRACTICE HORSE RACING, ETC. ETC. THE HON^T^^^ ADMIRAL ROUS. LONDON: A. H. BAILY & Co., EOYAL EXCHANGE BUILDINGS, COENHILL. 1866. LONDON : PRINTED BY W. CLOWES AND SONS, STAMFORD STREET, AND CHAKING CROSS. CONTENTS. Preface xi CHAPTER I. On the State of the English Turf in 1865 , . 1 CHAPTER II. On the State of the La^^ . 9 CHAPTER III. On the Rules of Racing 17 CHAPTER IV. On Starting—Riding Races—Jockeys .... 24 CHAPTER V. On the Rules of Betting 30 CHAPTER VI. On the Sale and Purchase of Horses .... 44 On the Office and Legal Responsibility of Stewards . 49 Clerk of the Course 54 Judge 56 Starter 57 On the Management of a Stud 59 vi Contents. KACma CASES. PAGE Horses of a Minor Age qualified to enter for Plates and Stakes 65 Jockey changed in a Race ...... 65 Both Jockeys falling abreast Winning Post . 66 A Horse arriving too late for the First Heat allowed to qualify 67 Both Horses thrown—Illegal Judgment ... 67 Distinction between Plate and Sweepstakes ... 68 Difference between Nomination of a Half-bred and Thorough-bred 69 Whether a Horse winning a Sweepstakes, 23 gs. each, three subscribers, could run for a Plate for Horses which never won 50^. ..... 70 Distance measured after a Race found short . 70 Whether a Compromise was forfeited by the Horse omitting to walk over 71 Whether the Winner distancing the Field is entitled to Second Money 71 A Horse objected to as a Maiden for receiving Second Money 72 Rassela's Case—Wrong Decision ... -

April 4-6 Contents

MEDIA GUIDE #TheWorldIsWatching APRIL 4-6 CONTENTS CHAIRMAN’S WELCOME 3 2018 WINNING OWNER 50 ORDER OF RUNNING 4 SUCCESSFUL OWNERS 53 RANDOX HEALTH GRAND NATIONAL FESTIVAL 5 OVERSEAS INTEREST 62 SPONSOR’S WELCOME 8 GRAND NATIONAL TIMELINE 64 WELFARE & SAFETY 10 RACE CONDITIONS 73 UNIQUE RACE & GLOBAL PHENOMENON 13 TRAINERS & JOCKEYS 75 RANDOX HEALTH GRAND NATIONAL ANNIVERSARIES 15 PAST RESULTS 77 ROLL OF HONOUR 16 COURSE MAP 96 WARTIME WINNERS 20 RACE REPORTS 2018-2015 21 2018 WINNING JOCKEY 29 AINTREE JOCKEY RECORDS 32 RACECOURSE RETIRED JOCKEYS 35 THIS IS AN INTERACTIVE PDF MEDIA GUIDE, CLICK ON THE LINKS TO GO TO THE RELEVANT WEB AND SOCIAL MEDIA PAGES, AND ON THE GREATEST GRAND NATIONAL TRAINERS 37 CHAPTER HEADINGS TO TAKE YOU INTO THE GUIDE. IRISH-TRAINED WINNERS 40 THEJOCKEYCLUB.CO.UK/AINTREE TRAINER FACTS 42 t @AINTREERACES f @AINTREE 2018 WINNING TRAINER 43 I @AINTREERACECOURSE TRAINER RECORDS 45 CREATED BY RACENEWS.CO.UK AND TWOBIRD.CO.UK 3 CONTENTS As April approaches, the team at Aintree quicken the build-up towards the three-day Randox Health Grand National Festival. Our first port of call ahead of the 2019 Randox welfare. We are proud to be at the forefront of Health Grand National was a media visit in the racing industry in all these areas. December, the week of the Becher Chase over 2019 will also be the third year of our the Grand National fences, to the yard of the broadcasting agreement with ITV. We have been fantastically successful Gordon Elliott to see delighted with their output and viewing figures, last year’s winner Tiger Roll being put through not only in the UK and Ireland, but throughout his paces. -

Kubota Equestrian Range

Kubota Equestrian range Kubota’s equestrian range combines power, reliability and operator comfort to deliver exceptional performance, whatever the task. Moulton Road, Kennett, Newmarket CB8 8QT Call Matthew Bailey on 01638 750322 www.tnsgroup.co.uk Thurlow Nunn Standen 1 ERNEST DOE YOUR TRUSTED NSFA NEW HOLLAND NEWMARKET STUD DEALER FARMERS ASSOCIATION Directory 2021 Nick Angus-Smith Chairman +44 (0) 777 4411 761 [email protected] Andrew McGladdery MRCVS Vice Chairman +44 (0)1638 663150 Michael Drake Company Secretary c/o Edmondson Hall Whatever your machinery requirements, we've got a solution... 25 Exeter Road · Newmarket · Suffolk CB8 8AR Contact Andy Rice on 07774 499 966 Tel: 01638 560556 · Fax: 01638 561656 MEMBERSHIP DETAILS AVAILABLE ON APPLICATION N.S.F.A. Directory published by Thoroughbred Printing & Publishing Mobile: 07551 701176 Email: [email protected] FULBOURN Wilbraham Road, Fulbourn CB21 5EX Tel: 01223 880676 2 3 CHAIRMAN’S FOREWORD AWARD WINNING SOLICITORS & It is my pleasure to again introduce readers to the latest Newmarket Stud Farmers Directory. SPORTS LAWYERS The 2020 Stud Season has been one of uncertainty but we are most fortunate that here in Newmarket we can call on the services of some of the world’s leading experts in their fields. We thank them all very much indeed for their advice. Especial thanks should be given to Tattersalls who have been able to conduct their sales in Newmarket despite severe restrictions. The Covid-19 pandemic has affected all our lives and the Breeding season was no exception. Members have of course complied with all requirements of Government with additional stringent safeguards agreed by ourselves and the Thoroughbred Breeders Association so the breeding season was able to carry on almost unaffected. -

T Am T Th T Be an C M in Fo Co Fa Gr W St Ch T Ra Sm in R No T Str W Fa

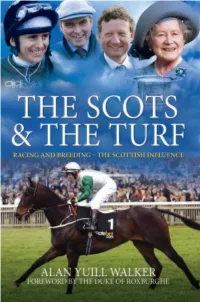

As a freelance writer, Alan Yuill Walker has spent The Scots & The Turf tells the story of the his life writing about racing and bloodstock. For amazing contribution made to the world of over forty years he was a regular contributor to Thoroughbred horseracing by the Scots and Horse & Hound and has had a long involvement those of Scottish ancestry, past and present. with the Thoroughbred Breeders’ Association. Throughout the years, this contribution has Other magazines/journals to which he has been across the board, from jockeys to trainers contributed on a regular basis include The and owners as well as some superb horses. British/European Racehorse, Stud & Stable, Currently, Scotland has a great ambassador in Pacemaker, The Thoroughbred Breeder and Mark Johnston, who has resurrected Middleham Thoroughbred Owner & Breeder. He was also in North Yorkshire as one of the country’s a leading contributor to The Bloodstock foremost training centres, while his jumping Breeders’ Annual Review. His previous books counterpart Alan King, the son of a Lanarkshire are Thoroughbred Studs of Great Britain, The farmer, is now based outside Marlborough. The History of Darley Stud Farms, Months of Misery greatest lady owner of jumpers in recent years Moments of Bliss, and Grey Magic. was Queen Elizabeth the Queen Mother, while Stirling-born Willie Carson was five-times champion jockey on the Flat. These are, of course, familiar names to any racing enthusiast but they represent just a small part of the Scottish connection that has influenced the Sport of Kings down the years. Recognition of the part played by those from north of the Border is long overdue and The Scots & The Turf now sets the record straight with a fascinating account of those who have helped make horseracing into the fabulous spectacle it is today. -

The Memoirs of AGA KHAN WORLD ENOUGH and TIME

The Memoirs of AGA KHAN WORLD ENOUGH AND TIME BY HIS HIGHNESS THE AGA KHAN, P.C., G.C.S.I., G.C.V.O., G.C.I.E. 1954 Simon and Schuster, New York Publication Information: Book Title: The Memoirs of Aga Khan: World Enough and Time. Contributors: Aga Khan - author. Publisher: Simon and Schuster. Place of Publication: New York. Publication Year: 1954. First Printing Library of Congress Catalogue Card Number: 54-8644 Dewey Decimal Classification Number: 92 MANUFACTURED IN THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA BY H. WOLFF BOOK MFG. CO., NEW YORK, N. Y. Publication Information: Book Title: The Memoirs of Aga Khan: World Enough and Time. Contributors: Aga Khan - author. Publisher: Simon and Schuster. Place of Publication: New York. Publication Year: 1954. Publication Information: Book Title: The Memoirs of Aga Khan: World Enough and Time. Contributors: Aga Khan - author. Publisher: Simon and Schuster. Place of Publication: New York. Publication Year: 1954. CONTENTS PREFACE BY W. SOMERSET MAUGHAM Part One: CHILDHOOD AND YOUTH I A Bridge Across the Years 3 II Islam, the Religion of My Ancestors 8 III Boyhood in India 32 IV I Visit the Western World 55 Part Two: YOUNG MANHOOD V Monarchs, Diplomats and Politicians 85 VI The Edwardian Era Begins 98 VIII Czarist Russia 148 VIII The First World War161 Part Three: THE MIDDLE YEARS IX The End of the Ottoman Empire 179 X A Respite from Public Life 204 XI Foreshadowings of Self-Government in India 218 XII Policies and Personalities at the League of Nations 248 Part Four: A NEW ERA XIII The Second World War 289 XIV Post-war Years with Friends and Family 327 XV People I Have Known 336 XVI Toward the Future 347 INDEX 357 Publication Information: Book Title: The Memoirs of Aga Khan: World Enough and Time. -

Rwitc, Ltd. Annual Auction Sale of Two Year Old Bloodstock 142 Lots

2020 R.W.I.T.C., LTD. ANNUAL AUCTION SALE OF TWO YEAR OLD BLOODSTOCK 142 LOTS ROYAL WESTERN INDIA TURF CLUB, LTD. Mahalakshmi Race Course 6 Arjun Marg MUMBAI - 400 034 PUNE - 411 001 2020 TWO YEAR OLDS TO BE SOLD BY AUCTION BY ROYAL WESTERN INDIA TURF CLUB, LTD. IN THE Race Course, Mahalakshmi, Mumbai - 400 034 ON MONDAY, Commencing at 4.00 p.m. FEBRUARY, 03RD (LOT NUMBERS 1 TO 71) AND TUESDAY, Commencing at 4.00 p.m. FEBRUARY, 04TH (LOT NUMBERS 72 TO 142) Published by: N.H.S. Mani Secretary & CEO, Royal Western India Turf Club, Ltd. eistere ce Race Course, Mahalakshmi, Mumbai - 400 034. Printed at: MUDRA 383, Narayan Peth, Pune - 411 030. IMPORTANT NOTICES ALLOTMENT OF RACING STABLES Acceptance of an entry for the Sale does not automatically entitle the Vendor/Owner of a 2-Year-Old for racing stable accommodation in Western India. Racing stable accommodation in Western India will be allotted as per the norms being formulated by the Stewards of the Club and will be at their sole discretion. THIS CLAUSE OVERRIDES ANY OTHER RELEVANT CLAUSE. For application of Ownership under the Royal Western India Turf Club Limited, Rules of Racing. For further details please contact Stipendiary Steward at [email protected] BUYERS BEWARE All prospective buyers, who intend purchasing any of the lots rolling, are requested to kindly note:- 1. All Sale Forms are to be lodged with a Turf Authority only since all foals born in 2018 are under jurisdiction of Turf Authorities with effect from Jan . -

Latest Open Race Details GBGB to Provide Grants for Vehicle Air Conditioning and Insulation

Vol 13 / No 9 7 May 2021 Fortnightly by Subscription calendar Latest Open Race Details GBGB to Provide Grants for Vehicle Air Conditioning and Insulation TOMMYS PLUTO (t1) on his way to victory in the Sprint Division 2 for trainer Claude Gardiner and owners Hovex Racing, scoring vital points for eventual winners Hove in the Photo: Steve Nash inaugural running of the RPGTV Entain Group Track Championship. FOR ALL THE LATEST NEWS - WWW.GBGB.ORG.UK Follow GBGB on Twitter @greyhoundboard @gbgbstaff and Instagram and Facebook CATEGORY ONE FINALS Date Distance/type Track Event Sun 09 May 480m Hurdle Central Park RPGTV Grand National Tue 18 May 500m Maidens Towcester KAB Maiden Derby Wed 19 May 480m Flat Newcastle Arena Racing Company Northern Flat Sat 22 May 900m Flat Monmore Green Ladbrokes TV Trophy Sat 29 May 659m Flat Yarmouth The George Ing St Leger Sat 26 Jun 714m Flat Crayford Ladbrokes Kent St Leger Sat 10 Jul 500m Flat Towcester Star Sports & TRC Events & Leisure English Greyhound Derby 2021 Sat 24 Jul 500m Puppies Towcester 5% Tote Juvenile Classic Sat 31 Jul 695m Flat Brighton & Hove Coral Regency Sat 31 Jul 515m Flat Brighton & Hove Coral Sussex Cup Sat 21 Aug 630m Flat Monmore Green Ladbrokes Summer Stayers Classic Sat 21 Aug 480m Flat Monmore Green Ladbrokes Gold Cup Sat 28 Aug 942m Flat Towcester 5% Tote Towcester Marathon Mon 30 Aug 500m Puppies Nottingham Arena Racing Company Puppy Classic Mon 30 Aug 500m Flat Nottingham Arena Racing Company Select Stakes Sat 11 Sep Tri-Distance Sheffield 3 Steps to Victory Thu 16 Sep 462m