Saving Schoodic: a Story of Development, Lost Settlement, and Preservation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Island Explorer Short Range Transit Plan

Island Explorer Short Range Transit Plan FINAL REPORT Prepared for the National Park Service and the Maine Department of Transportation May 21, 2007 ISLAND EXPLORER SHORT RANGE TRANSIT PLAN Table of Contents Chapter 1: Introduction and Summary 1.1 Introduction ___________________________________________________________________________ 1-1 1.3 Summary of Key findings________________________________________________________________ 1-3 Chapter 2: Review of Previous Studies 2.1 Phase 2 Report: Seasonal Public Transportation on MDI (1997) _________________________________ 2-1 2.2 Visitor Center and Transportation Facility Needs (2002) ________________________________________ 2-2 2.3 Intermodal Transportation Hub Charrette (2002) ______________________________________________ 2-2 2.4 Year-round Transit Plan for Mount Desert island (2003) ________________________________________ 2-3 2.5 Bangor-Trenton Transportation Alternatives Study (2004)_______________________________________ 2-3 2.6 Visitor Use Management Strategy for Acadia National Park (2003) _______________________________ 2-7 2.7 Visitor Capacity Charrette for Acadia National Park (2002)______________________________________ 2-9 2.8 Acadia National Park Visitor Census Reports (2002-2003) _____________________________________ 2-10 2.9 MDI Tomorrow Commu8nity Survey (2004) _______________________________________________ 2-12 2.10 Strategic Management Plan: Route 3 corridor and Trenton Village (2005) ________________________ 2-13 Chapter 3: Onboard Surveys of Island Explorer Passengers -

Winter 2016 Volume 21 No

Fall/Winter 2016 Volume 21 No. 3 A Magazine about Acadia National Park and Surrounding Communities Friends of Acadia Journal Fall/Winter 2016 1 President’s Message FOA AT 30 hen a handful of volunteers And the impact of this work extends at Acadia National Park and beyond Acadia: this fall I attended a Wforward-looking park staff to- conference at the Grand Canyon, where gether founded Friends of Acadia in 1986, I heard how several other friends groups their goal was to provide more opportuni- from around the country are modeling ties for citizens to give back to this beloved their efforts after FOA’s best practices place that gave them so much. Many were and historic successes. Closer to home, avid hikers willing to help with trail up- community members in northern Maine keep. Others were concerned about dwin- have already reached out to FOA for tips dling park funding coming from Washing- as they contemplate a friends group for the ton. Those living in the surrounding towns newly-established Katahdin Woods and shared a desire to help a large federal agen- Waters National Monument. cy better understand and work with our As the brilliant fall colors seemed to small Maine communities. hang on longer than ever at Acadia this These visionaries may or may not year, I enjoyed a late-October morning on have predicted the challenges and the Precipice Trail. The young peregrine opportunities facing Acadia at the dawn FOA falcons had fledged, and the re-opened trail of its second century—such as climate featured a few new rungs and hand-holds change, transportation planning, cruise and partners whom we hope will remain made possible by a generous FOA donor. -

Beaver Log Explore Acadia Checklist Island Explorer Bus See the Ocean and Forest from the Top of a Schedule Inside! Mountain

National Park Service Acadia National Park U.S. Department of the Kids Interior Acadia Beaver Log Explore Acadia Checklist Island Explorer Bus See the ocean and forest from the top of a Schedule Inside! mountain. Listen to a bubbly waterfall or stream. Examine a beaver lodge and dam. Hear the ocean waves crash into the shore. Smell a balsam fir tree. Camping & Picnicking Acadia's Partners Seasonal camping is provided within the park on Chat with a park ranger. Eastern National Bookstore Mount Desert Island. Blackwoods Campground is Eastern National is a non-profit partner which Watch the stars or look for moonlight located 5 miles south of Bar Harbor and Seawall provides educational materials such as books, shining on the sea. Campground is located 5 miles south of Southwest maps, videos, and posters at the Hulls Cove Visitor Hear the night sounds of insects, owls, Harbor. Private campgrounds are also found Center, the Sieur de Monts Nature Center, and the and coyote. throughout the island. Blackwoods Campground park campgrounds. Members earn discounts while often fills months in advance. Once at the park, Feel the sand and sea with your bare feet. supporting research and education in the park. For all sites are first come, first served. Reservations information visit: www.easternnational.org 2012 Observe and learn about these plants and in advance are highly recommended. Before you animals living in the park: arrive, visit www.recreation.gov Friends of Acadia bat beaver blueberry bush Friends of Acadia is an independent nonprofit Welcome to Acadia! cattail coyote deer Campground Fees & organization dedicated to ensuring the long-term Going Green in Acadia! National Parks play an important role in dragonfly frog fox Reservations protection of the natural and cultural resources Fare-free Island Explorer shuttle buses begin helping Americans shape a healthy lifestyle. -

The Gilded Age and the Making of Bar Harbor Author(S): Stephen J

The Gilded Age and the Making of Bar Harbor Author(s): Stephen J. Hornsby Source: Geographical Review, Vol. 83, No. 4 (Oct., 1993), pp. 455-468 Published by: American Geographical Society Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/215826 Accessed: 25/08/2008 18:13 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use, available at http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp. JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use provides, in part, that unless you have obtained prior permission, you may not download an entire issue of a journal or multiple copies of articles, and you may use content in the JSTOR archive only for your personal, non-commercial use. Please contact the publisher regarding any further use of this work. Publisher contact information may be obtained at http://www.jstor.org/action/showPublisher?publisherCode=ags. Each copy of any part of a JSTOR transmission must contain the same copyright notice that appears on the screen or printed page of such transmission. JSTOR is a not-for-profit organization founded in 1995 to build trusted digital archives for scholarship. We work with the scholarly community to preserve their work and the materials they rely upon, and to build a common research platform that promotes the discovery and use of these resources. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. http://www.jstor.org THE GILDED AGE AND THE MAKING OF BAR HARBOR* STEPHEN J. HORNSBY ABSTRACT. In the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, an American urban elite created an extensive North American pleasure periphery, with sea- sonal resorts that dramatically reshaped local economies and landscapes. -

Intelligent Transportation in Acadia National Park

INTELLIGENT TRANSPORTATION IN ACADIA NATIONAL PARK Determining the feasibility of smart systems to reduce traffic congestion An Interactive Qualifying Project Report submitted to the Faculty of the WORCESTER POLYTECHNIC INSTITUTE in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Bachelor of Science by Angela Calvi Colin Maki Mingqi Shuai Jackson Peters Daniel Wivagg Date: July 28, 2017 Approved: ______________________________________ Professor Frederick Bianchi, Advisor This report represents the work of one or more WPI undergraduate students. Submitted to the faculty as evidence of completion of a degree requirement. WPI routinely publishes these reports on its web site without editorial or peer review. i Abstract The goal of this project was to assess the feasibility of implementing an intelligent transportation system (ITS) in Acadia National Park. To this end, the features of an ITS were researched and discussed. The components of Acadia’s previous ITS were recorded and their effects evaluated. New technologies to implement, replace, or upgrade the existing ITS were researched and the companies providing these technologies were contacted and questioned for specifications regarding their devices. From this research, three sensor systems were identified as possibilities. These sensors were magnetometers, induction loops, and cameras. Furthermore, three methods of information dissemination were identified as useful to travelers. Those methods were dynamic message signs, websites, and mobile applications. The logistics of implementing these systems were researched and documented. A cost analysis was created for each system. The TELOS model of feasibility was then used to compare the strengths of each sensor in five categories: Technical, Economic, Legal, Operational and Schedule. Based on the results of the TELOS and cost analyses, the sensors were ranked in terms of feasibility; magnetometers were found to be the most feasible, followed by induction loop sensors and then camera-based systems. -

Sculpture Symposium SESSION I Message from the Maine Arts Commission

Sculpture Symposium SESSION I Message from the Maine Arts Commission Dear Friends, As we approach the second round of the Schoodic International Sculpture Symposium, I am struck by the wondrous manifestation of a seedling idea—how the expertise and enthusiasm of a few can energize a community beyond anything in recent memory. This project represents the fruits of the creative economy initiative in the most positive and startling way. Schoodic Peninsula, Maine Discussions for the Symposium began in 2005 around a table at the Schoodic section of Acadia National Contents Park. All the right aspects were aligned and the project was grass roots and supported by local residents. It Sculptors used indigenous granite; insisted on artistic excellence; and broadened the intelligence and significance of the project through international inclusion. The project included a core educational component and welcomed Dominika Griesgraber, Poland 4 tourism through on-site visits to view the artists at work. It placed the work permanently in surrounding communities as a marker of local support and appreciation for monumental public art. You will find no war Jo Kley, Germany 6 memorials among the group, no men on horseback. The acceptance by the participating communities of less literal and adventurous works of art is a tribute to the early and continual inclusion of resident involvement. Don Justin Meserve, Maine 8 It also emphasizes that this project is about beauty, not reverie for the past but a beacon toward a rejuvenated future. Ian Newbery, Sweden 10 The Symposium is a tour de force, an unparalleled success, and I congratulate the core group and all the Roy Patterson, Maine 12 surrounding communities for embracing the concept of public art. -

Surprising Revelations: Intimacies in the Letters Between Charles W

1 “Surprising Revelations: Intimacies in the Letters Between Charles W. Eliot, George B. Dorr & John D. Rockefeller Jr.” Ronald H. Epp, Ph.D. Jesup Memorial Library August 10, 2016 Earlier this year I proposed to Ruth Eveland several topics for a centennial presentation at the Jesup Memorial Library. The topic of intimacies in the letters of the most prominent park founders was strongly preferred. This is not a subject I discussed in my biography of George B. Dorr. Indeed, preparation of this talk forced my reopening of research materials which proved more challenging than I expected. I needed relaxation after fifteen years of research and writing, not re-immersion in the difficult craft of writing. But the topic was rich in potential and like Mr. Dorr I embrace the notion of persistence. So here I am in mid-August in one of four surviving island physical structures that bear the design imprint of Mr. Dorr (the others being Oldfarm’s Storm Beach Cottage, the park office at COA, and the park Abbe Museum). I am not here to talk about external manifestations of Dorr’s impact; nor will I enter here into the emphasis that other local historians have given to the differences between Dorr, Eliot, and Rockefeller. Frankly, my research has shown that their personalities were more similar than the dissimilarities promoted by Sargent Collier, R.W. Hale Jr., Judith S. Goldstein, and H. Eliot Foulds. All of us agree lon one point, however, that these park founders appreciate the achievements of one another, exchanged ideas, offered 2 encouragement, and expressed candid feelings about a wide array of topics. -

Schoodic Peninsula He Schoodic Peninsula, Narrow Gravel Road

National Park Service Acadia U.S. Department of the Interior Acadia National Park Schoodic Peninsula he Schoodic Peninsula, narrow gravel road. Although you can is located on the right, one-half mile containing the only section of drive up the one-mile road, you may down the road. Park here to access the TAcadia National Park on the also choose to walk one of the three Alder and Anvil Trails. The level and mainland, boasts granite headlands hiking trails that lead to the top. On easy Alder Trail begins across the road that bear erosional scars of storm a clear day from the summit, views from the entrance to the parking area. waves and flood tides. Although of the ocean, forests, and mountains The Anvil Trail, which leads to the similar in scenic splendor to portions claim your attention. 180-foot summit of the Anvil, begins of Mount Desert Island, the Schoodic several hundred yards down the road coast is more secluded. Returning to the main road, keep and around a curve. Both trails are right at the next intersection to reach marked with cedar posts. It is approximately a one-hour drive Schoodic Point. You will pass the from Hulls Cove Visitor Center entrance to the Schoodic Education Approximately two miles from the to the Schoodic Peninsula. In the and Research Center. The center, Blueberry Hill Parking Area, the park summer the Schoodic Peninsula is located on the site of a former U.S. ends at Wonsqueak Harbor. Two miles accessible via ferry service from Bar Navy base, promotes park science beyond the park is the village of Birch Harbor to Winter Harbor, and the and education activities and related Harbor and the intersection with Island Explorer bus service provides regional, national, and international Route 186. -

Schoodic Outdoors Brochure

Schoodic National Scenic Byway! Scenic National Schoodic 5 GREAT FRENCHMAN BAY CONSERVANCY ACADIA NATIONAL PARK hiking, biking and paddling on the on paddling and biking hiking, PLACES TO Discover the special places for for places special the Discover HANG OUT The Conservancy has built and maintains a system of trails Corea Heath: Access from Route 1 to West Bay Rd/Route The Schoodic District of Acadia National Park offers 7 miles of Tidal Falls Preserve: At this narrow opening between Taunton 186, then left on Route 195/Corea Rd to parking. The wooded hiking trails, plus hiking on 8.5 miles of off-road biking paths. SCENIC BYWAY SCENIC for public use—look for the blue blazes! Call 207-422-2328 or Bay and the ocean, the water races in and out with the tides visit frenchmanbay.org loop trail provides overlooks of the bog and beaver dams, These trails link the ocean shore to the mountains, and offer SCHOODIC NATIONAL NATIONAL SCHOODIC creating a “reversing falls” (suitable for paddling by experts only). lodges and tranquil water flows. Great bird watching. Trail Tucker Mountain: Access from Route 1 from informal a variety of hiking experiences. WELCOME TO THE THE TO WELCOME HikingHiking Headquarters for Frenchman Bay Conservancy, it is a great place parking on the old Route 1 road bed across and slightly to the length: 1.25-mile loop. The Corea Heath Division of the Photo courtesy of Frenchman Bay Conservancy Bay of Frenchman courtesy Photo for picnicking and wildlife viewing. National Wildlife Refuge is just south of the Corea Heath Photo courtesy of Larry Peterson Larry of courtesy Photo east of the Long Cove rest area. -

Schoodic General Management Plan Amendment Cover Illustration

National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior Acadia National Park Maine Schoodic General Management Plan Amendment Cover Illustration: Frederic Edwin Church (American, 1826–1900) Schoodic Peninsula from Mount Desert at Sunrise, 1850–1855 Oil on paperboard 229 x 349 mm (9 x 13 3/4 in) Cooper Hewitt, National Design Museum, Smithsonian Institution Gift of Louis P. Church, 1917-4-332 Photo: Matt Flynn Schoodic General Management Plan Amendment Acadia National Park, Maine National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior April 2006 Contents Introduction 1 Glossary 29 Foundation for the Plan 2 Bibliography 31 Background 2 Purpose and Need for the Plan 2 Park Setting 3 Appendices Natural Resources 4 Appendix A: Concept for the Schoodic Education Cultural Resources 5 and Research Center 32 Park Facilities 8 Appendix B: Record of Decision 34 Visitor Experience 9 Appendix C: Section 106 Consultation Park Mission, Purpose, and Signifi cance 11 Requirements for Planned Undertakings 40 Legislative History 12 Appendix D: Proposed Navy Base Building Planning Issues 13 Reuse 41 Management Goals 14 Appendix E: Design Guidelines for Schoodic Education and Research Center 42 Appendix F: Alternative Transportation Assessment The Plan 17 Summary 44 Overview 17 Management Zoning 17 Management Prescriptions 20 List of Figures Resource Management 20 Figure 1: Acadia National Park Visitor Use and Interpretation 21 Figure 2: Schoodic Peninsula and Surrounding Cooperative Efforts and Partnerships 26 Islands Operational Effi ciency 26 Figure 3: Existing Features – Schoodic District Figure 4: Existing Features – Former Navy Base Figure 5: Schoodic Management Zoning List of Contributors 28 Figure 6: Proposed Navy Base Building Reuse Little Moose Island Introduction The National Park Service acquired property prescriptions. -

Siew- De Mo Nts Establishing Dr

Abbe Museum - Siew- de Mo nts Establishing Dr. Abbe's Museum in Mr. Dorr's Park by Ronald J-l. Epp Ph.D. For nearl y fi fty yea r ( 188 1- 1928) th e path s of two prom in ent Bar Harbor res id ents intersected repeatedl y. Dr. Robert Abbe ( 185 1- 1928) and Mr. George B. Dorr (1853 -1 944) we re movi ng independ entl y in th e ame direction, ali gned with other summer and perm anent Hancock Co un ty re ident , towa rd improvi ng the qu ali ty of li fe on Moun t Desert Island (M DI ). In the la t ix yea rs of Dr. Abbe's li fe, Dorr and Abbe wo ul d share the pa th that led to a glade bes ide th e Springhouse at Sieur de Monts in Lafayette Nati onal Park. At thi s ite a museum of native America n artifacts was bein g erected that wo uld bea r Dr. Abbe' name. Unfo rtLmately, he would not witness its dedi ca ti on nor oversee its early development. In 2003 th e Abbe Museum celebrated its 75th anni ver ary; the same year marked th e I 50th ann iversa ry of Mr. Dorr 's birth.1 The intersecti on of th e interests of Dorr and Ab be, the exercise of their di stincti ve areas of experti se, and th eir shared va lue wou ld prove to be very important fo r th e developm ent of the ls land. -

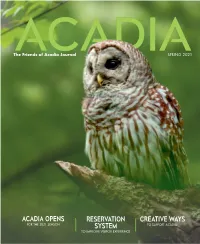

Spring 2021 Spring Creative Ways Ways Creative

ACADIA 43 Cottage Street, PO Box 45 Bar Harbor, ME 04609 SPRING 2021 Volume 26 No. 2 SPRING 2021 Volume The Friends of Acadia Journal SPRING 2021 MISSION Friends of Acadia preserves, protects, and promotes stewardship of the outstanding natural beauty, ecological vitality, and distinctive cultural resources of Acadia National Park and surrounding communities for the inspiration and enjoyment of current and future generations. VISITORS enjoy a game of cribbage while watching the sunset from Beech Mountain. ACADIA OPENS RESERVATION CREATIVE WAYS FOR THE 2021 SEASON SYSTEM TO SUPPORT ACADIA TO IMPROVE VISITOR EXPERIENCE ASHLEY L. CONTI/FOA friendsofacadia.org | 43 Cottage Street | PO Box 45 | Bar Harbor, ME | 04609 | 207-288-3340 | 800 - 625- 0321 PURCHASE YOUR PARK PASS! Whether walking, bicycling, riding the Island Explorer, or driving through the park, we all must obtain a park pass. Eighty percent of all fees paid in Acadia National Park stay in Acadia, to be used for projects that directly benefit park visitors and resources. BUY A PASS ONLINE AND PRINT Acadia National Park passes are available online: before you arrive at the park. This www.recreation.gov/sitepass/74271 allows you to drive directly to a Annual park passes are also available at trailhead/parking area & display certain Acadia-area town offices and local your pass from your vehicle. chambers of commerce. Visit www.nps.gov/acad/planyourvisit/fees.htm IN THIS ISSUE 10 8 12 20 18 FEATURES 6 REMEMBERING DIANNA EMORY Our Friend, Conservationist, and Defender of Acadia By David