Media Integrity Matters

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Besimtari 24.Indd

Gazetë mujore. Botues: Shoqata Bamirëse Islame Shkodër Viti III i botimit, Prill 2009 Nr. 24. Çmimi 20 lekë. www.gazetabesimtari.com; e-mail: [email protected] Kryeredaktor Selim Gokaj QQEVERISJAEVERISJA TTOLERANTEOLERANTE E PPERANDORISEERANDORISE OSMANEOSMANE NENE PALESTINEPALESTINE ë vitin 1514, sulltan Seli- mi mori Jerusalemin dhe zonën përreth tij dhe kë- shtu nisën 400 vitet e qe- verisjes osmane në Palesti- në.N Sikurse edhe në hapesirat e tjera te Pere- ndorise Osmane, kjo periudhë do t’i krijonte mundësinë Palestinës që të gëzonte paqe, stabilitet dhe të njihte bashkëjetesën har- monike të besimeve të ndryshme.Toleranca Islame vazhdoi në Perandorinë Osmane. Kisha, sinagoga dhe xhamia bashkëjetuan në paqe.Perandoria Osmane administrohej nën atë që njihej si “sistemi i kombit (mile- tit)”, ku tipari themelor i saj ishte që popujt lejoheshin të jetonin sipas besimeve të tyre edhe sipas sistemeve të veta ligjore. Të krish- terët dhe çifutët, të përshkruar si ‘Ithtarë të Librit’ në Kuran, gjetën tolerancë, siguri e liri në Perendorine Osmane.Arsyeja më e rëndësishme për këtë ishte qe, megjithëse Perandoria Osmane ishte një shtet Islamik e qeverisur nga myslimanët, ajo nuk dëshi- ronte t’i detyronte qytetarët e saj me forcë që të pranonin Islamin. Përkundrazi, shteti osman synonte të ofronte paqe e siguri për jomyslimanët dhe t’i qeveriste ata në një më- nyrë të tillë që ata të ndjeheshin të kënaqur me qeverisjen dhe drejtësinë Islamike.Shtete të tjera të mëdha të asaj kohe kishin mënyra qeverisjeje shumë të ashpra, shtypëse e jo- tolerante. Mbretëria e Spanjës nuk mund të toleronte ekzistencën e myslimanëve dhe të njëjtën mënyrë që kanë mbijetuar në botën ni. -

The News Media Industry Defined

Spring 2006 Industry Study Final Report News Media Industry The Industrial College of the Armed Forces National Defense University Fort McNair, Washington, D.C. 20319-5062 i NEWS MEDIA 2006 ABSTRACT: The American news media industry is characterized by two competing dynamics – traditional journalistic values and market demands for profit. Most within the industry consider themselves to be journalists first. In that capacity, they fulfill two key roles: providing information that helps the public act as informed citizens, and serving as a watchdog that provides an important check on the power of the American government. At the same time, the news media is an extremely costly, market-driven, and profit-oriented industry. These sometimes conflicting interests compel the industry to weigh the public interest against what will sell. Moreover, several fast-paced trends have emerged within the industry in recent years, driven largely by changes in technology, demographics, and industry economics. They include: consolidation of news organizations, government deregulation, the emergence of new types of media, blurring of the distinction between news and entertainment, decline in international coverage, declining circulation and viewership for some of the oldest media institutions, and increased skepticism of the credibility of “mainstream media.” Looking ahead, technology will enable consumers to tailor their news and access it at their convenience – perhaps at the cost of reading the dull but important stories that make an informed citizenry. Changes in viewer preferences – combined with financial pressures and fast paced technological changes– are forcing the mainstream media to re-look their long-held business strategies. These changes will continue to impact the media’s approach to the news and the profitability of the news industry. -

History and Development of the Communication Regulatory

HISTORY AND DEVELOPMENT OF THE COMMUNICATION REGULATORY AGENCY IN BOSNIA AND HERZEGOVINA 1998 – 2005 A thesis presented to the faculty of the College of Communication of Ohio University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Master of Arts Adin Sadic March 2006 2 This thesis entitled HISTORY AND DEVELOPMENT OF THE COMMUNICATION REGULATORY AGENCY IN BOSNIA AND HERZEGOVINA 1998 – 2005 by ADIN SADIC has been approved for the School of Telecommunications and the College of Communication by __________________________________________ Gregory Newton Associate Professor of Telecommunications __________________________________________ Gregory Shepherd Interim Dean, College of Communication 3 SADIC, ADIN. M.A. March 2006. Communication Studies History and Development of the Communication Regulatory Agency in Bosnia and Herzegovina 1998 – 2005 (247 pp.) Director of Thesis: Gregory Newton During the war against Bosnia and Herzegovina (B&H) over 250,000 people were killed, and countless others were injured and lost loved ones. Almost half of the B&H population was forced from their homes. The ethnic map of the country was changed drastically and overall damage was estimated at US $100 billion. Experts agree that misuse of the media was largely responsible for the events that triggered the war and kept it going despite all attempts at peace. This study examines and follows the efforts of the international community to regulate the broadcast media environment in postwar B&H. One of the greatest challenges for the international community in B&H was the elimination of hate language in the media. There was constant resistance from the local ethnocentric political parties in the establishment of the independent media regulatory body and implementation of new standards. -

UNDER ORDERS: War Crimes in Kosovo Order Online

UNDER ORDERS: War Crimes in Kosovo Order online Table of Contents Acknowledgments Introduction Glossary 1. Executive Summary The 1999 Offensive The Chain of Command The War Crimes Tribunal Abuses by the KLA Role of the International Community 2. Background Introduction Brief History of the Kosovo Conflict Kosovo in the Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia Kosovo in the 1990s The 1998 Armed Conflict Conclusion 3. Forces of the Conflict Forces of the Federal Republic of Yugoslavia Yugoslav Army Serbian Ministry of Internal Affairs Paramilitaries Chain of Command and Superior Responsibility Stucture and Strategy of the KLA Appendix: Post-War Promotions of Serbian Police and Yugoslav Army Members 4. march–june 1999: An Overview The Geography of Abuses The Killings Death Toll,the Missing and Body Removal Targeted Killings Rape and Sexual Assault Forced Expulsions Arbitrary Arrests and Detentions Destruction of Civilian Property and Mosques Contamination of Water Wells Robbery and Extortion Detentions and Compulsory Labor 1 Human Shields Landmines 5. Drenica Region Izbica Rezala Poklek Staro Cikatovo The April 30 Offensive Vrbovac Stutica Baks The Cirez Mosque The Shavarina Mine Detention and Interrogation in Glogovac Detention and Compusory Labor Glogovac Town Killing of Civilians Detention and Abuse Forced Expulsion 6. Djakovica Municipality Djakovica City Phase One—March 24 to April 2 Phase Two—March 7 to March 13 The Withdrawal Meja Motives: Five Policeman Killed Perpetrators Korenica 7. Istok Municipality Dubrava Prison The Prison The NATO Bombing The Massacre The Exhumations Perpetrators 8. Lipljan Municipality Slovinje Perpetrators 9. Orahovac Municipality Pusto Selo 10. Pec Municipality Pec City The “Cleansing” Looting and Burning A Final Killing Rape Cuska Background The Killings The Attacks in Pavljan and Zahac The Perpetrators Ljubenic 11. -

Authenticity in Electronic Dance Music in Serbia at the Turn of the Centuries

The Other by Itself: Authenticity in electronic dance music in Serbia at the turn of the centuries Inaugural dissertation submitted to attain the academic degree of Dr phil., to Department 07 – History and Cultural Studies at Johannes Gutenberg University Mainz Irina Maksimović Belgrade Mainz 2016 Supervisor: Co-supervisor: Date of oral examination: May 10th 2017 Abstract Electronic dance music (shortly EDM) in Serbia was an authentic phenomenon of popular culture whose development went hand in hand with a socio-political situation in the country during the 1990s. After the disintegration of Yugoslavia in 1991 to the moment of the official end of communism in 2000, Serbia was experiencing turbulent situations. On one hand, it was one of the most difficult periods in contemporary history of the country. On the other – it was one of the most original. In that period, EDM officially made its entrance upon the stage of popular culture and began shaping the new scene. My explanation sheds light on the fact that a specific space and a particular time allow the authenticity of transposing a certain phenomenon from one context to another. Transposition of worldwide EDM culture in local environment in Serbia resulted in scene development during the 1990s, interesting DJ tracks and live performances. The other authenticity is the concept that led me to research. This concept is mostly inspired by the book “Death of the Image” by philosopher Milorad Belančić, who says that the image today is moved to the level of new screen and digital spaces. The other authenticity offers another interpretation of a work, or an event, while the criterion by which certain phenomena, based on pre-existing material can be noted is to be different, to stand out by their specificity in a new context. -

SERBIA Jovanka Matić and Dubravka Valić Nedeljković

SERBIA Jovanka Matić and Dubravka Valić Nedeljković porocilo.indb 327 20.5.2014 9:04:47 INTRODUCTION Serbia’s transition to democratic governance started in 2000. Reconstruction of the media system – aimed at developing free, independent and pluralistic media – was an important part of reform processes. After 13 years of democratisation eff orts, no one can argue that a new media system has not been put in place. Th e system is pluralistic; the media are predominantly in private ownership; the legal framework includes European democratic standards; broadcasting is regulated by bodies separated from executive state power; public service broadcasters have evolved from the former state-run radio and tel- evision company which acted as a pillar of the fallen autocratic regime. However, there is no public consensus that the changes have produced more positive than negative results. Th e media sector is liberalized but this has not brought a better-in- formed public. Media freedom has been expanded but it has endangered the concept of socially responsible journalism. Among about 1200 media outlets many have neither po- litical nor economic independence. Th e only industrial segments on the rise are the enter- tainment press and cable channels featuring reality shows and entertainment. Th e level of professionalism and reputation of journalists have been drastically reduced. Th e current media system suff ers from many weaknesses. Media legislation is incom- plete, inconsistent and outdated. Privatisation of state-owned media, stipulated as mandato- ry 10 years ago, is uncompleted. Th e media market is very poorly regulated resulting in dras- tically unequal conditions for state-owned and private media. -

Youth of Action!

Seventeenth quarterly accession watch report YOUTH OF ACTION! April, 2013 Macedonian Centre for European Training and Foundation Open Society – Macedonia dedicate this report to the journalist and advocate for freedom of expression, Nikola Mladenov, and his eternal struggle “to clarify the matters”. youth OF action! Seventeenth quarterly accession watch report Publisher: Foundation Open Society - Macedonia For the publisher: Vladimir Milcin, Executive Director Prepared by: Macedonian Center for European Training and Foundation Open Society - Macedonia Proofreading and Translation into English: Abacus Design & Layout: Brigada design, Skopje Print: Propoint Circulation: 500 Free/Noncommercial circulation CIP - Каталогизација во публикација Национална и универзитетска библиотека "Св. Климент Охридски", Скопје 35.075.51:37(497.7)"2007/12"(047.31) МЛАДИ во акција! : седумнаесетти извештај од следењето на процесот на пристапување на Македонија во ЕУ. - Скопје : Фондација отворено општество - Македонија, 2013. - 90 стр. : илустр. ; 24 см Фусноти кон текстот ISBN 978-608-218-177-6 а) Национална агенција за европски образовни програми и мобилност - Македонија - 2007-2012 - Истражувања COBISS.MK-ID 93957386 CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Now we see Bosko Nelkoski, former Director of the National Agency, in an extended and upgraded version of the past. His character becomes All data collected as part of this research indicates to a reasonably more and more interesting. Bosko Nelkoski was appointed to the position grounded suspicion that in 2012 the -

People's Advocate… ………… … 291

REPUBLIC OF ALBANIA PEOPLE’S ADVOCATE ANNUAL REPORT On the activity of the People’s Advocate 1st January – 31stDecember 2013 Tirana, February 2014 REPUBLIC OF ALBANIA ANNUAL REPORT On the activity of the People’s Advocate 1st January – 31st December 2013 Tirana, February 2014 On the Activity of People’s Advocate ANNUAL REPORT 2013 Honorable Mr. Speaker of the Assembly of the Republic of Albania, Honorable Members of the Assembly, Ne mbeshtetje te nenit 63, paragrafi 1 i Kushtetutes se republikes se Shqiperise dhe nenit26 te Ligjit N0.8454, te Avokatit te Popullit, date 04.02.1999 i ndryshuar me ligjin Nr. 8600, date10.04.200 dhe Ligjit nr. 9398, date 12.05.2005, Kam nderin qe ne emer te Institucionit te Avokatit te Popullit, tj’u paraqes Raportin per veprimtarine e Avokatit te Popullit gjate vitit 2013. Pursuant “ to Article 63, paragraph 1 of the Constitution of the Republic of Albania and Article 26 of Law No. 8454, dated 04.02.1999 “On People’s Advocate”, as amended by Law No. 8600, dated 10.04.2000 and Law No. 9398, dated 12.05.2005, I have the honor, on behalf of the People's Advocate Institution, to submit this report on the activity of People's Advocate for 2013. On the Activity of People’s Advocate Sincerely, PEOPLE’S ADVOCATE Igli TOTOZANI ANNUAL REPORT 2013 Table of Content Prezantim i Raportit Vjetor 2013 8 kreu I: 1Opinione dhe rekomandime mbi situaten e te drejtave te njeriut ne Shqiperi …9 2) permbledhje e Raporteve te vecanta drejtuar Parlamentit te Republikes se Shqiperise......................... -

Marrëdhëniet Mes Medias Dhe Politikës Në Shqipëri

Marrëdhëniet mes medias dhe politikës në Shqipëri MARRËDHËNIETRINIA MES MEDIASSHQIPTARE 2011 DHE POLITIKËS NË SHQIPËRI Mes besimit për të ardhmen dhe dyshimit Rrapo Zguri për të tashmen! Alba Çela Tidita Fshazi Arbjan Mazniku Geron Kamberi Zyra e Tiranës Jonida Smaja – koordinatore e FES Rruga “Abdi Toptani”, Torre Drin, kati 3 P.O. Box 1418 Tirana, Albania Telefon: 00355 (0) 4 2250986 00355 (0) 4 2273306 Albanian Media Institute Homepage: http://www.fes.org.al Instituti Shqiptar i Medias 63 MARRËDHËNIET MES MEDIAS DHE POLITIKËS NË SHQIPËRI Marrëdhëniet mes medias dhe politikës në Shqipëri Marrëdhëniet mes medias dhe politikës në Shqipëri Rrapo Zguri Albanian Media Institute Instituti Shqiptar i Medias Tiranë, 2017 1 Marrëdhëniet mes medias dhe politikës në Shqipëri Botues: Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung Office Tirana Rr. Abdi Toptani Torre Drin, Kati i 3-të Kutia Postare 1418 Tiranë, ALBANIA Autor: Rrapo Zguri Realizoi monitorimet: Emirjon Senja Redaktor: Agim Doksani Kopertina: Bujar Karoshi Opinionet, gjetjet, konkluzionet dhe rekomandimet e shprehura në këtë botim janë të autorëve dhe nuk reflektojnë domosdoshmërisht ato të Fondacionit Friedrich Ebert. Publikimet e Fondacionit Friedrich Ebert nuk mund të përdoren për arsye komerciale pa miratim me shkrim. 2 Marrëdhëniet mes medias dhe politikës në Shqipëri PËRMBAJTJA E LËNDËS 1. Evoluimi i sistemit mediatik shqiptar gjatë viteve të tranzicionit ................................................................................. 6 2. Pavarësia e medias dhe e gazetarëve: garancitë dhe faktorët e riskut .................................................................... 18 2.1. Garancitë bazë të pavarësisë së medias në Shqipëri ............. 18 2.2. Kontrolli formal i medias nga politika .................................. 21 2.3. Pronësia dhe financimi i mediave.......................................... 25 2.4. Organizimi i mediave dhe i komunitetit të gazetarëve ........ -

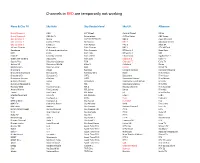

Channels in RED Are Temporarily Not Working

Channels in RED are temporarily not working Nova & Ote TV Sky Italy Sky Deutschland Sky UK Albanian Nova Cinema 1 AXN 13th Street Animal Planet 3 Plus Nova Cinema 2 AXN SciFi Boomerang At The Races ABC News Ote Cinema 1 Boing Cartoon Network BBC 1 Agon Channel Ote Cinema 2 Caccia e Pesca Discovery BBC 2 Albanian screen Ote Cinema 3 Canale 5 Film Action BBC 3 Alsat M Village Cinema Cartoonito Film Cinema BBC 4 ATV HDTurk Sundance CI Crime Investigation Film Comedy BT Sports 1 Bang Bang FOX Cielo Film Hits BT Sports 2 BBF FOXlife Comedy Central Film Select CBS Drama Big Brother 1 Greek VIP Cinema Discovery Film Star Channel 5 Club TV Sports Plus Discovery Science FOX Chelsea FC Cufo TV Action 24 Discovery World Kabel 1 Clubland Doma Motorvision Disney Junior Kika Colors Elrodi TV Discovery Dmax Nat Geo Comedy Central Explorer Shkence Discovery Showcase Eurosport 1 Nat Geo Wild Dave Film Aktion Discovery ID Eurosport 2 ORF1 Discovery Film Autor Discovery Science eXplora ORF2 Discovery History Film Drame History Channel Focus ProSieben Discovery Investigation Film Dy National Geographic Fox RTL Discovery Science Film Hits NatGeo Wild Fox Animation RTL 2 Disney Channel Film Komedi Animal Planet Fox Comedy RTL Crime Dmax Film Nje Travel Fox Crime RTL Nitro E4 Film Thriller E! Entertainment Fox Life RTL Passion Film 4 Folk+ TLC Fox Sport 1 SAT 1 Five Folklorit MTV Greece Fox Sport 2 Sky Action Five USA Fox MAD TV Gambero Rosso Sky Atlantic Gold Fox Crime MAD Hits History Sky Cinema History Channel Fox Life NOVA MAD Greekz Horror Channel Sky -

OBAVEZE POLITIČKE STRANKE Naziv Političke Stranke

2%$9(=(32/,7,ý.(675$1.( Obrazac 5 1D]LYSROLWLþNHVWUDQNHPARTIJA DEMOKRATSKOG PROGRESA 2EDYH]HSROLWLþNHVWUDQNHSRNUHGLWLPDLSR]DMPLFDPD GHWDOMLX 10.000,00 KM 2VWDOHREDYH]HSROLWLþNHVWUDQNH GHWDOMLX 498.926,91 KM 8.831(2%$9(=(32/,7,ý.(675$1.( 508.926,91 KM 2EDYH]HSROLWLþNHVWUDQNHSRNUHGLWLPDLSR]DMPLFDPD Iznos obaveze po 5RNYUDüDQMD osnovu kredita ili Red. Davalac kredita ili Iznos kredita ili Datum Naziv organizacionog dijela Visina rate kredita ili pozajmice na dan br. pozajmnice pozajmice realizacije pozajmice 31.12.2020 1 GLAVNI ODBOR IGOR CRNADAK 10.000,00 16.10.2020 0,00 15.10.2021 10.000,00 UKUPNO: 10.000,00 5.2 Ostale obaveze Iznos obaveze Red. Datum nastanka Naziv organizacionog dijela Povjerilac / obaveza na dan br. obaveze 31.12.2020 1 GRADSKI ODBOR BANJA LUKA ALF-OM DOO 1.1.2020 44,60 2 GRADSKI ODBOR BANJA LUKA AQUA TIM DISTRIBUCIJA DOO 1.1.2020 280,00 Godišnji 01.01.-31.12.2020 1 od 14 3 GRADSKI ODBOR BANJA LUKA %$/.$1.23Ĉ85Ĉ(9$.GRR 1.1.2020 660,00 4 GRADSKI ODBOR BANJA LUKA )272./,.VS5$1.2û8.29,û 1.1.2020 600,00 5 GRADSKI ODBOR BANJA LUKA HOTEL BOSNA 1.1.2020 100,00 6 GRADSKI ODBOR BANJA LUKA +27(/9,'29,û 1.1.2020 8.916,50 7 GRADSKI ODBOR BANJA LUKA ,1)2&205$ý81$5, 1.1.2020 571,60 8 GRADSKI ODBOR BANJA LUKA KECKOM DOO 1.1.2020 2.921,13 9 GRADSKI ODBOR BANJA LUKA KMC DOO 1.1.2020 8.870,35 10 GRADSKI ODBOR BANJA LUKA LLJ Božana Šipka sp 1.1.2020 1.895,40 11 GRADSKI ODBOR BANJA LUKA MAKOPRINT DOO 1.1.2020 428,81 12 GRADSKI ODBOR BANJA LUKA 0(*$35,17VS$EDGåLþ,JRU 1.1.2020 1.591,20 13 GRADSKI ODBOR BANJA LUKA 0,/$VS%LOMDQD7RPLü 1.1.2020 -

Evolution of the Media Market and Its Legal Framework in Bosnia and Herzegovina Since the Independence: Special Focus on Defamation

Evolution of the media market and its legal framework in Bosnia and Herzegovina since the independence: special focus on defamation Kristina Cendic http://hdl.handle.net/10803/397684 ADVERTIMENT . L'accés als continguts d'aquesta tesi doctoral i la seva utilització ha de respectar els drets de la persona autora. Pot ser utilitzada per a consulta o estudi personal, així com en activitats o materials d'investigació i docència en els termes establerts a l'art. 32 del Text Refós de la Llei de Propietat Intel·lectual (RDL 1/1996). Per altres utilitzacions es requereix l'autorització prèvia i expressa de la persona autora. En qualsevol cas, en la utilització dels seus continguts caldrà indicar de forma clara el nom i cognoms de la persona autora i el títol de la tesi doctoral. No s'autoritza la seva reproducció o altres formes d'explotació efectuades amb finalitats de lucre ni la seva comunicació pública des d'un lloc aliè al servei TDX. Tampoc s'autoritza la presentació del seu contingut en una finestra o marc aliè a TDX (framing). Aquesta reserva de drets afecta tant als continguts de la tesi com als seus resums i índexs. ADVERTENCIA. El acceso a los contenidos de esta tesis doctoral y su utilización debe respetar los derechos de la persona autora. Puede ser utilizada para consulta o estudio personal, así como en actividades o materiales de investigación y docencia en los términos establecidos en el art. 32 del Texto Refundido de la Ley de Propiedad Intelectual (RDL 1/1996). Para otros usos se requiere la autorización previa y expresa de la persona autora.