Briefing Paper 14

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Life Expectancy Trends Within Glasgow, 2001-2009

Glasgow: health in a changing city a descriptive study of changes in health, demography, housing, socioeconomic circumstances and environmental factors in Glasgow over the last 20 years Bruce Whyte March 2016 Contents Acknowledgements 3 Abbreviations/glossary 3 Executive summary 7 1. Introduction 9 2. Background 10 3. Aims and methods 14 4. An overview of changes in demography, housing, socioeconomic circumstances and environmental factors in Glasgow 17 5. Changes in life expectancy in Glasgow 38 6. Discussion 52 7. Policy implications 57 8. Conclusions 61 Appendices 62 References 65 2 Acknowledgements I would like to thank Craig Waugh and Lauren Schofield (both of ISD Scotland) who helped produce the GCPH’s local health profiles for Glasgow. Much of the data shown or referred to in this report has been drawn from the profiles. Thank you also to Ruairidh Nixon who summarised trends in key health and social indicators in an internal GCPH report; some of that work is incorporated in this report. I would also like to thank Alan MacGregor (DRS, Glasgow City Council), who provided data on housing tenure, completions and demolitions. I am grateful to my colleagues at the GPCH who have commented on this work as it has developed, in particular, Carol Tannahill, David Walsh, Sara Dodds, Lorna Kelly and Joe Crossland. I would also like to thank Jan Freeke (DRS, Glasgow City Council) who commented on drafts of the report. Members of the GCPH Management Board have also provided useful advice and comments at various stages in the analysis. 3 Abbreviations/glossary Organisations DRS Development and Regeneration Services. -

Glasgow City Health and Social Care Partnership Health Contacts

Glasgow City Health and Social Care Partnership Health Contacts January 2017 Contents Glasgow City Community Health and Care Centre page 1 North East Locality 2 North West Locality 3 South Locality 4 Adult Protection 5 Child Protection 5 Emergency and Out-of-Hours care 5 Addictions 6 Asylum Seekers 9 Breast Screening 9 Breastfeeding 9 Carers 10 Children and Families 12 Continence Services 15 Dental and Oral Health 16 Dementia 18 Diabetes 19 Dietetics 20 Domestic Abuse 21 Employability 22 Equality 23 Health Improvement 23 Health Centres 25 Hospitals 29 Housing and Homelessness 33 Learning Disabilities 36 Maternity - Family Nurse Partnership 38 Mental Health 39 Psychotherapy 47 NHS Greater Glasgow and Clyde Psychological Trauma Service 47 Money Advice 49 Nursing 50 Older People 52 Occupational Therapy 52 Physiotherapy 53 Podiatry 54 Rehabilitation Services 54 Respiratory Team 55 Sexual Health 56 Rape and Sexual Assault 56 Stop Smoking 57 Volunteering 57 Young People 58 Public Partnership Forum 60 Comments and Complaints 61 Glasgow City Community Health & Care Partnership Glasgow Health and Social Care Partnership (GCHSCP), Commonwealth House, 32 Albion St, Glasgow G1 1LH. Tel: 0141 287 0499 The Management Team Chief Officer David Williams Chief Officer Finances and Resources Sharon Wearing Chief Officer Planning & Strategy & Chief Social Work Officer Susanne Miller Chief Officer Operations Alex MacKenzie Clincial Director Dr Richard Groden Nurse Director Mari Brannigan Lead Associate Medical Director (Mental Health Services) Dr Michael Smith -

Campus Travel Guide Final 08092016 PRINT READY

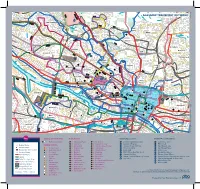

Lochfauld V Farm ersion 1.1 27 Forth and 44 Switchback Road Maryhill F C Road 6 Clyde Canal Road Balmore 1 0 GLASGOW TRANSPORT NETWORK 5 , 6 F 61 Acre0 A d Old Blairdardie oa R Drumchapel Summerston ch lo 20 til 23 High Knightswood B irkin e K F 6 a /6A r s de F 15 n R F 8 o Netherton a High d 39 43 Dawsholm 31 Possil Forth and Clyde Canal Milton Cadder Temple Gilshochill a 38 Maryhill 4 / 4 n F e d a s d /4 r a 4 a o F e River Lambhill R B d Kelvin F a Anniesland o 18 F 9 0 R 6 n /6A 1 40 r 6 u F M 30 a b g Springburn ry n h 20 i ill r R Ruchill p Kelvindale S Scotstounhill o a Balornock 41 d Possil G Jordanhill re Park C at 19 15 W es 14 te rn R 17 37 oa Old Balornock 2 d Forth and D um Kelvinside 16 Clyde b North art 11 Canal on Kelvin t Ro Firhill ad 36 ee 5 tr 1 42 Scotstoun Hamiltonhill S Cowlairs Hyndland 0 F F n e 9 Broomhill 6 F ac 0 r Maryhill Road V , a ic 6 S Pa tor Dowanhill d r ia a k D 0 F o S riv A 8 21 Petershill o e R uth 8 F 6 n F /6 G r A a u C 15 rs b R g c o u n Whiteinch a i b r 7 d e Partickhill F 4 p /4 S F a River Kelvin F 9 7 Hillhead 9 0 7 River 18 Craighall Road Port Sighthill Clyde Partick Woodside Forth and F 15 Dundas Clyde 7 Germiston 7 Woodlands Renfrew Road 10 Dob Canal F bie' 1 14 s Loa 16 n 5 River Kelvin 17 1 5 F H il 7 Pointhouse Road li 18 5 R n 1 o g 25A a t o Shieldhall F 77 Garnethill d M 15 n 1 14 M 21, 23 10 M 17 9 6 F 90 15 13 Alexandra Parade 12 0 26 Townhead 9 8 Linthouse 6 3 F Govan 33 16 29 Blyt3hswood New Town F 34, 34a Anderston © The University of Glasgo North Stobcross Street Cardonald -

New Stobhill Hospital the New Stobhill Ambulatory Care Hospital Belmont (ACH) Is Set in the Stobhill Campus

To Bishopbriggs FIF New Stobhill station E WAY New Stobhill Hospital The New Stobhill Ambulatory Care Hospital Belmont (ACH) is set in the Stobhill campus. The campus Hospital D Centre A O houses the hospital, a minor injuries unit, a R L L Marie Curie number of general and specialist mental health Walking and cycling guide 2021 HI Hospice Y facilities, and a brand new purpose-built Marie RA G Curie Cancer Care hospice. L BA A LORNOCK ROAD B The ACH provides outpatient clinics, day surgery and diagnostic services. There are hospital beds available to medics to extend the range of short B ALORNOCK ROAD stay surgical procedures offered to patients. B A L Skye House O At the main entrance there is a staffed help desk R N O and patient information points which provide C K R travel information, health promotion and other O A D advice. BELMONT ROAD Stobhill Hospital 2 new mental health wards are now on the campus. The two wards – Elgin and Appin – have space for up to 40 inpatients, with Elgin To Springburn dedicated to adult acute mental health inpatient station care and Appin focusing on older adults with functional mental health issues. Cycle Parking Entrance Rowanbank Bus stop Clinic BALORNOCK ROAD Active Travel Cycling to Work NHS Greater Glasgow & Clyde recognise that New Stobhill Hospital is well served by public transport The Cycle to Work scheme is a salary sacrifice scheme physical activity is essential for good health covering bus travel within the immediate area and available to NHS Greater Glasgow & Clyde staff*. -

Flat 0/2, 198 Broomfield Road, Balornock, G21 3UF INTERIORS & SPECIFICATION

ESTATE AGENTS LETTINGS FLAT 0/2, 198 BROOMFIELD ROAD, BALORNOCK, G21 3UF INTERIORS & SPECIFICATION Flat 0/2, 198 Broomfield Road, Balornock, G21 3UF Large traditional ground floor flat occupying an admired setting opposite Springburn Park. Spacious accommodation comprises vestibule, reception hallway, bay windowed lounge, modern fitted kitchen, dining room, two bedrooms, bathroom and additional shower room / study. Gas central heating. Private gardens to the front of flat and communal drying green to the rear. The property is situated within a two storey blond sandstone building, within close proximity of a range of amenities. This apartment would prove to be an ideal starter home or “buy to let” investment. Ref: L1195 FLOOR PLAN & SIZES BATH BEDROOM LOUNGE ROOM 1 C SHWR HALL ROOM DINING BEDROOM ROOM 2 KITCHEN LOUNGE 5.45m x 3.78m KITCHEN 2.90m x 1.80m DINING ROOM 2.97m x 2.73m BEDROOM 1 4.48m x 2.10m BEDROOM 2 4.35m x 2.12m BATHROOM 4.48m x 1.20m SHOWER ROOM 3.50m x 1.80m Multimap - Standard print - Location Page 1 of 1 Head from Robroyston on Wallacewell Road taking the right turning LOCATION & TRAVEL DIRECTIONS at road end into Balornock Road. Proceed up-hill turning left into Broomfield Road, where number 198 can be found on your left hand side. Map location FACILITIES UK/ Scotland/ City of Glasgow/ Possil Park INCLUSIONS: The inclusions are subject to negotiation. RECREATION: Balornock is very well served for the sporting enthusiast with a selection of facilities available on ones door step including a Golf Club, private Gym, Bowling Club, Tennis Club and Rugby Club. -

72 Bus Time Schedule & Line Route

72 bus time schedule & line map 72 Kirkintilloch - Glasgow View In Website Mode The 72 bus line (Kirkintilloch - Glasgow) has 2 routes. For regular weekdays, their operation hours are: (1) Glasgow: 6:40 AM - 6:30 PM (2) Kirkintilloch: 7:35 AM - 6:30 PM Use the Moovit App to ƒnd the closest 72 bus station near you and ƒnd out when is the next 72 bus arriving. Direction: Glasgow 72 bus Time Schedule 53 stops Glasgow Route Timetable: VIEW LINE SCHEDULE Sunday Not Operational Monday 6:40 AM - 6:30 PM Kelvin Court Kelvin Court, Scotland Tuesday 6:40 AM - 6:30 PM Catherine Street, Kirkintilloch Wednesday 6:40 AM - 6:30 PM Cowgate, Scotland Thursday 6:40 AM - 6:30 PM Freeland Place, Kirkintilloch Friday 6:40 AM - 6:30 PM Townhead, Scotland Saturday 6:40 AM - 6:30 PM Woodhead Avenue, Kirkintilloch Parliament Road, Kirkintilloch Lithgow Avenue, Kirkintilloch Glencairn Street, Kirkintilloch 72 bus Info Direction: Glasgow Woodilee Industrial Estate, Kirkintilloch Stops: 53 Trip Duration: 52 min Larkƒeld Centre, Lenzie Line Summary: Kelvin Court, Catherine Street, Kirkintilloch, Freeland Place, Kirkintilloch, Woodhead Easter Garngaber Rd, Lenzie Avenue, Kirkintilloch, Lithgow Avenue, Kirkintilloch, Woodilee Industrial Estate, Kirkintilloch, Larkƒeld Lomond Rd, Lenzie Centre, Lenzie, Easter Garngaber Rd, Lenzie, Lomond Rd, Lenzie, Lenzie Railway Station, Lenzie, Glenhead Lenzie Railway Station, Lenzie Road, Lenzie, Millersneuk Avenue, Lenzie, Cyprian Station Road, Kirkintilloch Drive, Lenzie, Gadloch Avenue, Auchinloch, Stepps Road, Wester Auchinloch, -

Demographic Change in Glasgow City and Neighbourhoods

Glasgow City Council Briefing Paper by Executive Director of Development and Regeneration Services Contact: Jan Freeke Phone: (0141) 287 8647 People and Households in Glasgow Current Estimates and Projected Changes 2010-2035 Demographic Change in Glasgow City and Neighbourhoods Date of Issue: 30 August 2012 PLEASE NOTE THE FOLLOWING: Any Ordnance Survey mapping included within this Report is provided by Glasgow City Council under licence from the Ordnance Survey in order to fulfil its public function to make available Council-held public domain information. Persons viewing this mapping should contact Ordnance Survey Copyright for advice where they wish to licence Ordnance Survey mapping/map data for their own use. The OS web site can be found at <http://www.ordnancesurvey.co.uk> " If accessing this Report via the Internet, please note that any mapping is for illustrative purposes only and is not true to any marked scale 1. INTRODUCTION 1.1 On 19th April 2012, the Executive Director of Development and Regeneration Services published a briefing paper on the results, for Glasgow, of the 2010-base population projections prepared by National Records of Scotland (NRS). The paper gave also the main results of the household projections, prepared by Council staff, based on the NRS population projections. 1.2 On 14th June 2012 NRS published a set of sub-national household projections, based on the same 2010-base population projections. There are some differences in the results of the two household projections (NRS projections and GCC variant). These differences will be briefly discussed in a later section of this paper. Unless stated otherwise, the household projection results presented in this paper are those of the GCC variant projections. -

GNHS Newsletter 2 Apr 2018

GLASGOW NATURAL April 2018 HISTORY SOCIETY Newsletter Editor NEWSLETTER David Palmar Next Newsletter Deadline [email protected] 22 July 2018 GNHS is a Registered Scottish Charity www.gnhs.org.uk 2018 Meetings - in the University of Glasgow Boyd Orr Building unless stated April Tuesday 10th 7.00pm Graham Kerr Building, Lecture Theatre 1 Lecture in two halves with tea break between: Behind the Naturalist’s Lens: the photographic work and contribution to Natural History of Charles Eric Palmar (supported by the BLB bequest); David Palmar and colleagues May Tuesday 8th Graham Kerr Building, Lecture Theatre 1 7.15pm Lecture 1: The aspen project; Peter Livingstone Lecture 2: An eye for the unusual: the herbarium of Peter Macpherson; Keith Watson June Saturday 9th Graham Kerr Building, Lecture Theatre 1 Conference: The Amphibians and Reptiles of Scotland: Current Research, Future Challenges; see next page for details Tuesday 19th Summer Social: see page 16 for details and booking form. Members are welcome to join the speaker(s) and Council at pre-lecture meals, normally held in Cafe Andaluz. Please inform Mary Child by the Sunday before a Tuesday lecture if you would like to attend. The cost is £10 per head, subsidised by the BLB fund. Winter Programme 2018-19 It is time to assemble next session’s programme of evening talks- so please send any ideas you have for speakers/topics Roger Downie as soon as you can. A reminder of the timing and format of most meetings (except April 10th): 1. There will normally be only one talk each evening (occasionally two short talks). -

Glasgow Fare Zone Map.Ai

Haldane Balloch Kilsyth Fare Zone Map Campsie Glen Napierston Lennoxtown Milton of Alexandria Campsite Strathblane Road Bonhill ZONE Craigton Road at Lynn Drive Village Renton at Stockiemuir Road Milngavie Cumbernauld Bellsmyre Local 3 Helensburgh Torrance Harestanes Westcliff Old Kilpatrick HMP Kirkintilloch Craiglinn Dumbarton Roman Crescent Low Moss Westfield Milton Faifley Old Kilpatrick Bowling Waterside Duntocher Strathkelvin Retail Park Gallowhill Condorrat ZONE Singer Hazel Avenue Station Westerhill Lenzie Mollinsburn Dalmuir City 2 Flyover Drumchapel Clydebank City Zone 1 Boundaries Bishopbriggs Moodiesburn ZONE Bus Station Summerston Chryston M80 slip road Milton 1 ....... Dumbarton Road at Tunnel Exit Clydebank Knightswood 8 9 Crowwood 2 ....... Park Drive South at Balshagray Avenue Auchinairn 7 Muirhead Local 3 3 ....... Victoria Park Drive North at Balshagray Avenue Cadder 10 Robroyston 6 4 ....... Crow Road at Balshagray Avenue Maryhill 11 5 ....... Anniesland Cross Yoker 5 Ruchill ZONE Balornock 6 ....... Maryhill Road at Library Wyndford ZONE 12 Barmulloch 7 ....... Balmore Road at Skirsa Street Renfrew 8 ....... Milton Terminus Scotstoun 4 Broomhill Springburn13 Craigend 9 ....... Springburn Road at Colston Road City 1 3 Kelvinbridge 14 City 2 Braehead 10 ....... Balgrayhill Road at Colston Road 2 Garthamlock 11 ....... Belmont Road at Balgrayhill Road Partick 1 University Easterhouse 12 of Glasgow ....... Broomfield Road at Syrian Street Glasgow Airport 13 QEUH Riddrie ....... Red Road at Broomfield Road 33 Linthouse 15 14 ....... Royston Road at Langdale Street Bargeddie 32 16 15 ....... Cumbernauld Road at Dee Street Govan Glasgow Alexandra Crossroads Carntyne (A89/A752) 16 ....... Edinburgh Road at Cumbernauld Road City Centre Park 17 ZONE 17 ....... Carntyne Road at Rigby Street Penilee Cardonald Coatbridge Airdrie 18 ...... -

Glasgow City North (Potentially Vulnerable Area 11/15)

Glasgow City north (Potentially Vulnerable Area 11/15) Local Plan District Local authority Main catchment Clyde and Loch Lomond Glasgow City Council, North East Glasgow Lanarkshire Council Summary of flooding impacts Summary of flooding impacts flooding of Summary At risk of flooding • 710 residential properties • 410 non-residential properties • £750,000 Annual Average Damages (damages by flood source shown left) Summary of objectives to manage flooding Objectives have been set by SEPA and agreed with flood risk management authorities. These are the aims for managing local flood risk. The objectives have been grouped in three main ways: by reducing risk, avoiding increasing risk or accepting risk by maintaining current levels of management. Objectives Many organisations, such as Scottish Water and energy companies, actively maintain and manage their own assets including their risk from flooding. Where known, these actions are described here. Scottish Natural Heritage and Historic Environment Scotland work with site owners to manage flooding where appropriate at designated environmental and/or cultural heritage sites. These actions are not detailed further in the Flood Risk Management Strategies. Summary of actions to manage flooding The actions below have been selected to manage flood risk. Flood Natural flood New flood Community Property level Site protection protection management warning flood action protection plans scheme/works works groups scheme Actions Flood Natural flood Maintain flood Awareness Surface water Emergency protection -

8A Bus Time Schedule & Line Route

8A bus time schedule & line map 8A Parkhead - Maryhill via Provanmill, Springburn View In Website Mode The 8A bus line (Parkhead - Maryhill via Provanmill, Springburn) has 2 routes. For regular weekdays, their operation hours are: (1) Maryhill: 7:55 PM (2) Riddrie: 6:24 PM - 7:22 PM Use the Moovit App to ƒnd the closest 8A bus station near you and ƒnd out when is the next 8A bus arriving. Direction: Maryhill 8A bus Time Schedule 72 stops Maryhill Route Timetable: VIEW LINE SCHEDULE Sunday 11:42 AM - 7:42 PM Monday 7:55 PM Riddrie Library, Riddrie Tuesday 7:55 PM Hallbrae Street, Provanmill Wednesday 7:55 PM Lochwood Street, Provanmill Thursday 7:55 PM Moodiesburn Street, Provanmill Friday 7:55 PM Molendinar Gardens, Glasgow Saturday 7:55 PM Greenrig Street, Provanmill Lochgreen Street, Provanmill Lochgreen Street, Glasgow 8A bus Info Greenside Street, Provanmill Direction: Maryhill Stops: 72 Robroyston Road, Barmulloch Trip Duration: 52 min Line Summary: Riddrie Library, Riddrie, Hallbrae Olive Street, Barmulloch Street, Provanmill, Lochwood Street, Provanmill, Moodiesburn Street, Provanmill, Greenrig Street, Robroyston Road, Glasgow Provanmill, Lochgreen Street, Provanmill, Greenside Quarrywood Road, Barmulloch Street, Provanmill, Robroyston Road, Barmulloch, Olive Street, Barmulloch, Quarrywood Road, Barmulloch, Business Park, Robroyston, Asda Business Park, Robroyston Supermarket, Robroyston, Business Park, Robroyston, Quarrywood Road, Barmulloch, Asda Supermarket, Robroyston Robroyston Road, Barmulloch, Zena Place, Barmulloch, Quarrywood -

2Nd Glasgow Scout Group

2ND GLASGOW SCOUT GROUP 71 GLENCAIRN DRIVE GLASGOW G414PN 100% 30TH GLASGOW SCOUT GROUP 37 LAMMERMOOR AVENUE GLASGOW G523BE 100% 360 DEGREES FINANCE LTD 40 WASHINGTON STREET GLASGOW G38AZ 100% 360CRM LTD 80 ST VINCENT STREET GLASGOW 25% 3RD GLASGOW SCOUT GROUP 121 SHAWMOSS ROAD GLASGOW G414AE 100% 43RD GLASGOW SCOUT GROUP 4 HOLMHEAD ROAD GLASGOW G443AS 100% 4C DESIGN LIMITED 100 BORRON STREET GLASGOW 25% 4C DESIGN LTD 100 BORRON STREET GLASGOW 25% 50TH GLASGOW SCOUT GROUP 23 GARRY STREET GLASGOW G444AZ 100% 55 NORTH LTD 19 WATERLOO STREET GLASGOW G26AY 100% 55 NORTH LTD 19 WATERLOO STREET GLASGOW G26AY 100% 7 SEATER CENTRE (SCOTLAND) LTD 1152 TOLLCROSS ROAD GLASGOW G328HE 100% 72ND GLASGOW SCOUT GROUP 500 A CROW ROAD GLASGOW G117DW 100% 86TH/191 GLASGOW SCOUT GROUP 79 SANDA STREET GLASGOW G208PT 100% 965 LTD 965 DUKE STREET GLASGOW 100% 9TH GLASGOW SCOUT GROUP 99 THORNWOOD PLACE GLASGOW 100% A & E BROWN (PLUMBERS MERCHANTS) LTD 1320 SPRINGBURN ROAD GLASGOW G211UT 25% A & F MCKINNON LTD 391 VICTORIA ROAD GLASGOW G428RZ 100% A & G INVESTMENTS LLP 12 RENFIELD STREET GLASGOW 100% A & G INVESTMENTS LLP 12 RENFIELD STREET GLASGOW 100% A& L LTD 12 PLEAN STREET GLASGOW G140YH 25% A & M TRAINING LTD 28 ADAMSWELL STREET GLASGOW 100% A & P MACINTYRE LTD 213 CLARKSTON ROAD GLASGOW G443DS 25% A A MENZIES & CO 180 QUEEN MARGARET DRIVE GLASGOW G208NX 100% A A MOTORS LTD 7 MORDAUNT STREET GLASGOW 50% A ALEXANDER & SON (ELECTRICAL) LTD 9 CATHKINVIEW ROAD GLASGOW G429EH 25% A ALEXANDER & SON(ELECTRICAL) LTD 24 LOCHLEVEN ROAD GLASGOW G429JU 100% A B FRAMING