“Supreme and Fiery Force” by Carmen Acevedo Butcher

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cycles and Concentricity in Hildegard of Bingen's Scivias in Ma

Sylvie Thode Mount Menoikeion Seminar June 2018 Over and Over: Cycles and Concentricity in Hildegard of Bingen’s Scivias In many religions, and especially within various Christian traditions, repetition is used as penance: a priest might tell a Catholic parishioner to repeat five Hail Mary prayers and five Our Father’s as punishment for some sin. In a more drastic example, a monk from the Middle Ages might take to flagellating himself repeatedly for something as small as an impure thought, or just simply to connect with the pain Christ felt at the Crucifixion. However, repetition can also represent moments of praise or exaltation: one need only think of Handel’s Hallelujah Chorus. In traditions outside Christianity as well repetitive acts of devotion are used to celebrate God and achieve closeness with the divine force. In the Turkish sect of Sufism, a mystical strain of Islam, people known as whirling dervishes twirl in a circle over and over until they essentially lose all sense of where they are, and are said to access a high plane, closer to God’s divinity. One of the key figures of Christian mysticism, St. Hildegard of Bingen who lived in Germany during the 12th century, is especially exemplary of the power of repetitive, devotional motions of prayer. Hildegard is most well-known for her extensive visions of God, the Trinity, the Universe, and Heaven: she recorded these visions in a book called Scivias, which is a truncated form of the theological phrase Sci Vias Domini, or “know the ways of the Lord.” The book is divided into three “books,” a numerological allusion to the Trinity, with each book being a collection of individual visions. -

Medieval Representations of Satan Morgan A

Rollins College Rollins Scholarship Online Master of Liberal Studies Theses 2011 The aS tanic Phenomenon: Medieval Representations of Satan Morgan A. Matos [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.rollins.edu/mls Part of the Christianity Commons, and the History of Christianity Commons Recommended Citation Matos, Morgan A., "The aS tanic Phenomenon: Medieval Representations of Satan" (2011). Master of Liberal Studies Theses. 28. http://scholarship.rollins.edu/mls/28 This Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by Rollins Scholarship Online. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master of Liberal Studies Theses by an authorized administrator of Rollins Scholarship Online. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Satanic Phenomenon: Medieval Representations of Satan A Project Submitted in Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Liberal Studies By Morgan A. Matos July, 2011 Mentor: Dr. Steve Phelan Rollins College Hamilton Holt School Winter Park Master of Liberal Studies Program The Satanic Phenomenon: Medieval Representations of Satan Project Approved: _________________________________________ Mentor _________________________________________ Seminar Director _________________________________________ Director, Master of Liberal Studies Program ________________________________________ Dean, Hamilton Holt School Rollins College i Table of Contents Table of Contents i Table of Illustrations ii Introduction 1 1. Historical Development of Satan 4 2. Liturgical Drama 24 3. The Corpus Christi Cycle Plays 32 4. The Morality Play 53 5. Dante, Marlowe, and Milton: Lasting Satanic Impressions 71 Conclusion 95 Works Consulted 98 ii Table of Illustrations 1. Azazel from Collin de Plancy’s Dictionnaire Infernal, 1825 11 2. Jesus Tempted in the Wilderness, James Tissot, 1886-1894 13 3. -

Great Cloud of Witnesses.Indd

A Great Cloud of Witnesses i ii A Great Cloud of Witnesses A Calendar of Commemorations iii Copyright © 2016 by The Domestic and Foreign Missionary Society of The Protestant Episcopal Church in the United States of America Portions of this book may be reproduced by a congregation for its own use. Commercial or large-scale reproduction for sale of any portion of this book or of the book as a whole, without the written permission of Church Publishing Incorporated, is prohibited. Cover design and typesetting by Linda Brooks ISBN-13: 978-0-89869-962-3 (binder) ISBN-13: 978-0-89869-966-1 (pbk.) ISBN-13: 978-0-89869-963-0 (ebook) Church Publishing, Incorporated. 19 East 34th Street New York, New York 10016 www.churchpublishing.org iv Contents Introduction vii On Commemorations and the Book of Common Prayer viii On the Making of Saints x How to Use These Materials xiii Commemorations Calendar of Commemorations Commemorations Appendix a1 Commons of Saints and Propers for Various Occasions a5 Commons of Saints a7 Various Occasions from the Book of Common Prayer a37 New Propers for Various Occasions a63 Guidelines for Continuing Alteration of the Calendar a71 Criteria for Additions to A Great Cloud of Witnesses a73 Procedures for Local Calendars and Memorials a75 Procedures for Churchwide Recognition a76 Procedures to Remove Commemorations a77 v vi Introduction This volume, A Great Cloud of Witnesses, is a further step in the development of liturgical commemorations within the life of The Episcopal Church. These developments fall under three categories. First, this volume presents a wide array of possible commemorations for individuals and congregations to observe. -

Chapter 4 Video, “Chaucer’S England,” Chronicles the Development of Civilization in Medieval Europe

Toward a New World 800–1500 Key Events As you read, look for the key events in the history of medieval Europe and the Americas. • The revival of trade in Europe led to the growth of cities and towns. • The Catholic Church was an important part of European people’s lives during the Middle Ages. • The Mayan, Aztec, and Incan civilizations developed and administered complex societies. The Impact Today The events that occurred during this time period still impact our lives today. • The revival of trade brought with it a money economy and the emergence of capitalism, which is widespread in the world today. • Modern universities had their origins in medieval Europe. • The cultures of Central and South America reflect both Native American and Spanish influences. World History—Modern Times Video The Chapter 4 video, “Chaucer’s England,” chronicles the development of civilization in medieval Europe. Notre Dame Cathedral Paris, France 1163 Work begins on Notre Dame 800 875 950 1025 1100 1175 c. 800 900 1210 Mayan Toltec control Francis of Assisi civilization upper Yucatán founds the declines Peninsula Franciscan order 126 The cathedral at Chartres, about 50 miles (80 km) southwest of Paris, is but one of the many great Gothic cathedrals built in Europe during the Middle Ages. Montezuma Aztec turquoise mosaic serpent 1325 1453 1502 HISTORY Aztec build Hundred Montezuma Tenochtitlán on Years’ War rules Aztec Lake Texcoco ends Empire Chapter Overview Visit the Glencoe World History—Modern 1250 1325 1400 1475 1550 1625 Times Web site at wh.mt.glencoe.com and click on Chapter 4– Chapter Overview to 1347 1535 preview chapter information. -

God S Heroes

PUBLISHING GROUP:PRODUCT PREVIEW God’s Heroes A Child’s Book of Saints Children look up to and admire their heroes – from athletes to action figures, pop stars to princesses.Who better to admire than God’s heroes? This book introduces young children to 13 of the greatest heroes of our faith—the saints. Each life story highlights a particular virtue that saint possessed and relates the virtue to a child’s life today. God’s Heroes is arranged in an easy-to-follow format, with informa- tion about a saint’s life and work on the left and an fund activity on the right to reinforce the learning. Of the thirteen saints fea- tured, most will be familiar names for the children.A few may be new, which offers children the chance to get to know other great heroes, and maybe pick a new favorite! The 13 saints include: • St. Francis of Assisi 32 pages, 6” x 9” #3511 • St. Clare of Assisi • St. Joan of Arc • Blessed Kateri Tekakwitha • St. Philip Neri • St. Edward the Confessor In this Product Preview you’ll find these sample pages . • Table of Contents (page 1) • St. Francis of Assisi (pages 12-13) • Blessed Kateri Tekakwitha (pages 28-29) « Scroll down to view these pages. God’s Heroes A Child’s Book of Saints Featuring these heroes of faith and their timeless virtues. St. Mary, Mother of God . .4 St. Thomas . .6 St. Hildegard of Bingen . .8 St. Patrick . .10 St. Francis of Assisi . .12 St. Clare of Assisi . .14 St. Philip Neri . -

Susan K. Roll

Susan K. Roll Hildegard of Bingen: a Doctor of the Church On October 7, 2012, I was privileged to be present at the outdoor papal Mass at the Vatican in which Hildegard of Bingen was officially declared a Doctor of the Church. On October 26 I was even more privileged to be invited to give the opening address at the First International Conference of the Scivias Institut. As a member of the Scivias Institut from the beginning, I was pleased that this conference took place less than three weeks after Hildegard (finally!) received public recognition of her genius and of her contribution both to the Roman Catholic Church and to human creativity and knowledge, both scientific and mystical. In this article I will give some of the background and significance of the title “Doctor of the Church,” then briefly sketch the steps involved in Hildegard’s case. We will mention briefly the loose ends that remain in ascertaining the exact motive. Finally, to expand the context somewhat, we will take a glance at a sampling of contemporary commentaries that illustrates the rather odd situation today in which a medieval nun seems to have become, if not “all things to all people,” then certainly many very different things to various groups of people who want nothing to do with each other. The first point to note is that “Doctor of the Church” is conferred as an honorary title. It is not based on original research nor on the formal academic achievements equivalent to those of a person who holds a university Doctor title today. -

53Rd International Congress on Medieval Studies

53rd International Congress on Medieval Studies May 10–13, 2018 Medieval Institute College of Arts and Sciences Western Michigan University 1903 W. Michigan Ave. Kalamazoo, MI 49008-5432 wmich.edu/medieval 2018 i Table of Contents Welcome Letter iii Registration iv-v On-Campus Housing vi-vii Food viii-ix Travel x Driving and Parking xi Logistics and Amenities xii-xiii Varia xiv Off-Campus Accommodations vx Hotel Shuttle Routes xvi Hotel Shuttle Schedules xvii Campus Shuttles xviii Mailings xix Exhibits Hall xx Exhibitors xxi Plenary Lectures xxii Reception of the Classics in the Middle Ages Lecture xxiii Screenings xxiv Social Media xxv Advance Notice—2019 Congress xxvi The Congress: How It Works xxvii The Congress Academic Program xxviii-xxix Travel Awards xxx The Otto Gründler Book Prize xxxi Richard Rawlinson Center xxxii Center for Cistercian and Monastic Studies xxxiii M.A. Program in Medieval Studies xxxiv Medieval Institute Publications xxxv Endowment and Gift Funds xxxvi 2018 Congress Schedule of Events 1–192 Index of Sponsoring Organizations 193–198 Index of Participants 199–218 Floor Plans M-1 – M-9 List of Advertisers Advertising A-1 – A-36 Color Maps ii Dear colleagues, It’s a balmy 9 degrees here in Kalamazoo today, but I can’t complain—too much— because Kalamazoo will not feel the wrath of the “bomb cyclone” and polar vortex due to hit the East Coast later this week, the first week of 2018. Nonetheless, today in Kalamazoo, I long for spring and what it brings: the warmth of the weather, my colleagues and friends who will come in May to the International Congress on Medieval Studies. -

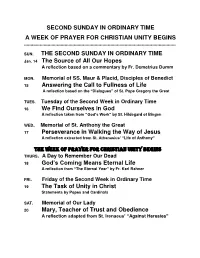

Second Sunday in Ordinary Time a Week of Prayer For

SECOND SUNDAY IN ORDINARY TIME A WEEK OF PRAYER FOR CHRISTIAN UNITY BEGINS …………………………………………………………………………………………………….. SUN. THE SECOND SUNDAY IN ORDINARY TIME Jan. 14 The Source of All Our Hopes A reflection based on a commentary by Fr. Demetrius Dumm MON. Memorial of SS. Maur & Placid, Disciples of Benedict 15 Answering the Call to Fullness of Life A reflection based on the “Dialogues” of St. Pope Gregory the Great TUES. Tuesday of the Second Week in Ordinary Time 16 We Find Ourselves in God A reflection taken from “God’s Work” by St. Hildegard of Bingen WED. Memorial of St. Anthony the Great 17 Perseverance in Walking the Way of Jesus A reflection extracted from St. Athanasius’ “Life of Anthony” The Week of Prayer for Christian Unity Begins THURS. A Day to Remember Our Dead 18 God’s Coming Means Eternal Life A reflection from “The Eternal Year” by Fr. Karl Rahner FRI. Friday of the Second Week in Ordinary Time 19 The Task of Unity in Christ Statements by Popes and Cardinals SAT. Memorial of Our Lady 20 Mary, Teacher of Trust and Obedience A reflection adapted from St. Irenaeus’ “Against Heresies” THE SOURCE OF ALL OUR HOPE A reflection adapted from a commentary by Fr. Demetrius Dumm In John’s version of the call of the first disciples, we read that Jesus had been pointed out to two of them by John; they then followed him, literally. “When he turned and saw them following him, he asked: What are you looking for? They said, Rabbi, where are you staying?” It would be a mistake to see this as simply an account of a friendly exchange between Jesus and the two disciples. -

Message of His Holiness Pope Francis to Participants in The

N. 201008a Thursday 08.10.2020 Message of His Holiness Pope Francis to participants in the webinar promoted by the Women’s Consultation Group of the Pontifical Council for Culture, “Women Read Pope Francis: reading, reflection and music” The following is the message sent by the Holy Father Francis to participants in the webinar promoted by the Women’s Consultation Group of the Pontifical Council for Culture, which took place yesterday, on the theme “Women Read Pope Francis: reading, reflection and music”: Message of the Holy Father Dear Friends, I offer a warm greeting to you, the Women’s Consultation Group of the Pontifical Council for Culture, on the occasion of the seminar “Women Read Pope Francis: Reading, Reflection and Music”, a series of meetings that now begins with the theme “Evangelii Gaudium”. Your gathering today highlights the novelty that you represent within the Roman Curia. For the first time, a Dicastery has involved a group of women by making them protagonists in developing cultural projects and approaches, and not simply to deal with women’s issues. Your Consultation Group is made up of women engaged in different sectors of the life of society and reflecting cultural and religious visions of the world that, however different, converge on the goal of working together in mutual respect. For your reading programme, you have chosen three of my writings: the Apostolic Exhortation Evangelii Gaudium, the Encyclical Letter Laudato Si’ and the Document on Human Fraternity for World Peace and Living Together. These works are devoted, respectively, to the themes of evangelization, creation and fraternity. -

The Avant-Garde in Jazz As Representative of Late 20Th Century American Art Music

THE AVANT-GARDE IN JAZZ AS REPRESENTATIVE OF LATE 20TH CENTURY AMERICAN ART MUSIC By LONGINEU PARSONS A DISSERTATION PRESENTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA 2017 © 2017 Longineu Parsons To all of these great musicians who opened artistic doors for us to walk through, enjoy and spread peace to the planet. ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I would like to thank my professors at the University of Florida for their help and encouragement in this endeavor. An extra special thanks to my mentor through this process, Dr. Paul Richards, whose forward-thinking approach to music made this possible. Dr. James P. Sain introduced me to new ways to think about composition; Scott Wilson showed me other ways of understanding jazz pedagogy. I also thank my colleagues at Florida A&M University for their encouragement and support of this endeavor, especially Dr. Kawachi Clemons and Professor Lindsey Sarjeant. I am fortunate to be able to call you friends. I also acknowledge my friends, relatives and business partners who helped convince me that I wasn’t insane for going back to school at my age. Above all, I thank my wife Joanna for her unwavering support throughout this process. 4 TABLE OF CONTENTS page ACKNOWLEDGMENTS .................................................................................................. 4 LIST OF EXAMPLES ...................................................................................................... 7 ABSTRACT -

Jazz at the Crossroads)

MUSIC 127A: 1959 (Jazz at the Crossroads) Professor Anthony Davis Rather than present a chronological account of the development of Jazz, this course will focus on the year 1959 in Jazz, a year of profound change in the music and in our society. In 1959, Jazz is at a crossroads with musicians searching for new directions after the innovations of the late 1940s’ Bebop. Musical figures such as Miles Davis and John Coltrane begin to forge a new direction in music building on their previous success earlier in the fifties. The recording Kind of Blue debuts in 1959 documenting the work of Miles Davis’ legendary sextet with John Coltrane, Cannonball Adderley, Bill Evans, Paul Chambers and Jimmy Cobb and reflects a new direction in the music with the introduction of a modal approach to composition and improvisation. John Coltrane records Giant Steps the culmination of the harmonic intricacies of Bebop and at the same time the beginning of something new. Ornette Coleman arrives in New York and records The Shape of Jazz to Come, an LP that presents a radical departure from the orthodoxies of Be-Bop. Dave Brubeck records Time Out, a record featuring a new approach to rhythmic structure in the music. Charles Mingus records Mingus Ah Um, establishing Mingus as a pre-eminent composer in Jazz. Bill Evans forms his trio with Scott LaFaro and Paul Motian transforming the interaction and function of the rhythm section. The quiet revolution in music reflects a world that is profoundly changed. The movement for Civil Rights has begun. The Birmingham boycott and the Supreme Court decision Brown vs. -

Dypdykk I Musikkhistorien - Del 25: Sun Ra (16.09.2019 - TFB) Oppdatert 16.09.2019

Dypdykk i musikkhistorien - Del 25: Sun Ra (16.09.2019 - TFB) Oppdatert 16.09.2019 Spilleliste pluss noen ekstra lyttetips: Intro Enlightment (Nuits De La Fondation Maeght Volume 1 (1970) / Sun Ra) Inspirasjon Fletcher Henderson Anitras dance [1939] / The John Kirby Sextet (The eternal myth revealed vol. 1 : 1926-1959 (2011) [14 CD-box] / Sun Ra) Drums of passion (1959) / Olatunji! Tidlige år / Arrangør / R&B Doo wop / Singler Jitterbuggin [1948] / The Red Saunders Orchestra Smile [1949] / Sun Ra You go to my head [1949] / The Sonny Blunt Trio Call my baby [1953] / Jo Jo Adams w/ The Red Saunders Orchestra The best things in life are free [1953] / Sun Ra Velvet [1956] / The Sun Ra Bebop Band (The eternal myth revealed vol. 1 : 1926-1959 (2011) [14 CD-box] / Sun Ra) I am a instrument ; I am strange [195?] / Sun Ra Spaceship lullaby ; A foggy day / The Nu Sounds (Singles : the definitive 45s collection 1952-1991 (2016) / Sun Ra) Daddy’s gonna tell you no lie ; Bye bye / The Cosmic Rays (Singles : the definitive 45s collection 1952-1991 (2016) / Sun Ra) M uck m uck (Matt matt) ; Hot skillet momma (Singel, 1957) / Yochanan 1 Arkestra Jazz by Sun Ra (1957) Høyt tempo Enlightenment ; Ancient aiethopia (Jazz in silhouette [1958](1959) / Sun Ra and his Arkestra) Diverse Music from tomorrows world [1960](2002) / Sun Ra and his Arkestra The invisible shield [1961-1963, 1970] (1974) / Sun Ra and his Intergalactic Research Arkestra Cluster of galaxies ; Infinity of the universe ; Solar drums (Art forms of dimensions tomorrow [1961-62] / Sun Ra and his Solar Arkestra) Brazilian sun (When sun comes out (1963) / Sun Ra and his Myth Science Arkestra) Adventure equation ; Moon dance ; Thither and Yon (Cosmic tones for mental therapy [1963](1967) / Sun Ra and his Myth Science Arkestra) Atlantis ; Mu ; Yucatan #1 [Hohner clavinet] (Atlantis [1967-1968](1969) / Sun Ra and his Astro-Infinity Arkestra) The perfect man (My brother the wind vol.