The Bhagavad-Gita

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Dr Anupama.Pdf

NJESR/July 2021/ Vol-2/Issue-7 E-ISSN-2582-5836 DOI - 10.53571/NJESR.2021.2.7.81-91 WOMEN AND SAMSKRIT LITERATURE DR. ANUPAMA B ASSISTANT PROFESSOR (VYAKARNA SHASTRA) KARNATAKA SAMSKRIT UNIVERSITY BENGALURU-560018 THE FIVE FEMALE SOULS OF " MAHABHARATA" The Mahabharata which has The epics which talks about tradition, culture, laws more than it talks about the human life and the characteristics of male and female which most relevant to this modern period. In Indian literature tradition the Ramayana and the Mahabharata authors talks not only about male characters they designed each and every Female characters with most Beautiful feminine characters which talk about their importance and dutiful nature and they are all well in decision takers and live their lives according to their decisions. They are the most powerful and strong and also reason for the whole Mahabharata which Occur. The five women in particular who's decision makes the whole Mahabharata to happen are The GANGA, SATYAVATI, AMBA, KUNTI and DRUPADI. GANGA: When king shantanu saw Ganga he totally fell for her and said "You must certainly become my wife, whoever you may be." Thus said the great King Santanu to the goddess Ganga who stood before him in human form, intoxicating his senses with her superhuman loveliness 81 www.njesr.com The king earnestly offered for her love his kingdom, his wealth, his all, his very life. Ganga replied: "O king, I shall become your wife. But on certain conditions that neither you nor anyone else should ever ask me who I am, or whence I come. -

A Comprehensive Guide by Jack Watts and Conner Reynolds Texts

A Comprehensive Guide By Jack Watts and Conner Reynolds Texts: Mahabharata ● Written by Vyasa ● Its plot centers on the power struggle between the Kaurava and Pandava princes. They fight the Kurukshetra War for the throne of Hastinapura, the kingdom ruled by the Kuru clan. ● As per legend, Vyasa dictates it to Ganesha, who writes it down ● Divided into 18 parvas and 100 subparvas ● The Mahabharata is told in the form of a frame tale. Janamejaya, an ancestor of the Pandavas, is told the tale of his ancestors while he is performing a snake sacrifice ● The Genealogy of the Kuru clan ○ King Shantanu is an ancestor of Kuru and is the first king mentioned ○ He marries the goddess Ganga and has the son Bhishma ○ He then wishes to marry Satyavati, the daughter of a fisherman ○ However, Satyavati’s father will only let her marry Shantanu on one condition: Shantanu must promise that any sons of Satyavati will rule Hastinapura ○ To help his father be able to marry Satyavati, Bhishma renounces his claim to the throne and takes a vow of celibacy ○ Satyavati had married Parashara and had a son with him, Vyasa ○ Now she marries Shantanu and has another two sons, Chitrangada and Vichitravirya ○ Shantanu dies, and Chitrangada becomes king ○ Chitrangada lives a short and uneventful life, and then dies, making Vichitravirya king ○ The King of Kasi puts his three daughters up for marriage (A swayamvara), but he does not invite Vichitravirya as a possible suitor ○ Bhishma, to arrange a marriage for Vichitravirya, abducts the three daughters of Kasi: Amba, -

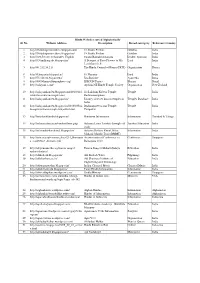

Judges of the Supreme Court of India and the High Courts

AS ON 01/03/2017 JUDGES OF THE SUPREME COURT OF INDIA AND THE HIGH COURTS (List of Judges arranged according to date of initial appointment) AS ON 01/03/2017 SUPREME COURT OF INDIA Sanctioned Judge Strength: 31 (List of Judges arranged according to date of appointment) Sl. Name of the Judge Date of Date of REMARKS No. S/Shri Justice appointment Retirement [Parent High Court] 1 JAGDISH SINGH KHEHAR 13/09/2011 27/08/2017 CJI w.e.f. 04/01/2017 PUNJAB & HARYANA 2 DIPAK MISRA 10/10/2011 02/10/2018 ORISSA 3 JASTI CHELAMESWAR 10/10/2011 22/06/2018 ANDHRA PRADESH 4 RANJAN GOGOI 23/04/2012 17/11/2019 GAUHATI 5 MADAN BHIMARAO LOKUR 04/06/2012 30/12/2018 DELHI 6 PINAKI CHANDRA GHOSE 08/03/2013 27/05/2017 CALCUTTA 7 KURIAN JOSEPH 08/03/2013 29/11/2018 KERALA 8 ARJAN KUMAR SIKRI 12/04/2013 06/03/2019 DELHI 9 SHARAD ARVIND BOBDE 12/04/2013 23/04/2021 BOMBAY 10 RAJESH KUMAR AGRAWAL 17/02/2014 04/05/2018 ALLAHABAD 11 NUTHALAPATI VENKATA RAMANA 17/02/2014 26/08/2022 ANDHRA PRADESH 12 ARUN KUMAR MISHRA 07/07/2014 02/09/2020 MADHYA PRADESH 13 ADARSH KUMAR GOEL 07/07/2014 06/07/2018 PUNJAB & HARYANA 14 ROHINTON FALI NARIMAN 07/07/2014 12/08/2021 BAR 15 ABHAY MANOHAR SAPRE 13/08/2014 27/08/2019 MADHYA PRADESH 16 SMT. R. BANUMATHI 13/08/2014 19/07/2020 MADRAS 17 PRAFULLA CHANDRA PANT 13/08/2014 29/08/2017 UTTARAKHAND 18 UDAY UMESH LALIT 13/08/2014 08/11/2022 BAR 19 AMITAVA ROY 27/02/2015 28/02/2018 GAUHATI 20 AJAY MANIKRAO KHANWILKAR 13/05/2016 29/07/2022 BOMBAY 21 DR. -

Bhagavad Gita Free

öËÅ Ç⁄∞¿Ë⁄“®¤ Ñ∆ || ¥˘®Ωæ Ã˘¤-í‹¡ºÎ ≤Ÿ¨ºÎ —∆Ÿ´ºŸ¿Ÿº® æË⁄í≤Ÿ | é∆ƒºÎ ¿Ÿú-æËíŸæ “ Ÿé¿Å || “§-⁄∆YŸºÎ ⁄“ º´—æ‰≥Æ˙-íË¿’-ÇŸYŸÅ ⁄∆úŸ≤™‰ | —∆Ÿ´ºŸ¿ŸºÅ Ǩ∆Ÿ æËí¤ úŸ≤¤™‰ ™ ÇŸ¿Ëß‹ºÎ ÑôöËÅ Ç⁄∞¿Ë⁄“®¤ Ñ∆ || ¥˘®Ωæ Ã˘¤-í‹¡ºÎ ≤Ÿ¨ºÎ —∆Ÿ´ºŸ¿Ÿº‰® æË⁄í≤Ÿ | éÂ∆ƒºÎ ¿Ÿú ºŸ¿ŸºÅ é‚¥Ÿé¿Å || “§-⁄∆YŸºÎ ⁄“ º´—æ‰≥Æ˙-íË¿’-ÇŸYŸÅ ⁄∆úŸ≤™‰ | —∆Ÿ´ºŸ¿ŸºÅ Ǩ∆Ÿ æËí¤ ¿Ÿú-æËíºÎ ÇŸ¿Ëß‹ºÎ ÑôöËÅ Ç⁄∞¿Ë⁄“®¤ Ñ∆ || ¥˘®Ωæ Ã˘¤-í‹¡ºÎ ≤Ÿ¨ºÎ —∆Ÿ´ºŸ¿Ÿº‰® æË⁄í≤Ÿ 韺Π∞%‰ —∆Ÿ´ºŸ¿ŸºÅ é‚¥Ÿé¿Å || “§-⁄∆YŸºÎ ⁄“ º´—æ‰≥Æ˙-íË¿’-ÇŸYŸÅ ⁄∆úŸ≤™‰ | —∆Ÿ´ºŸ¿Ÿº ∫Ÿú™‰ ¥˘Ë≤Ù™-¿Ÿú-æËíºÎ ÇŸ¿Ëß‹ºÎ ÑôöËÅ Ç⁄∞¿Ë⁄“®¤ Ñ∆ || ¥˘®Ωæ Ã˘¤-í‹¡ºÎ ≤Ÿ¨ºÎ —∆Ÿ´ºŸ¿Ÿ §-¥˘Æ¤⁄¥éŸºÎ ∞%‰ —∆Ÿ´ºŸ¿ŸºÅ é‚¥Ÿé¿Å || “§-⁄∆YŸºÎ ⁄“ º´—æ‰≥Æ˙-íË¿’-ÇŸYŸÅ ⁄∆úŸ≤™‰ | -⁄∆YŸ | ⁄∆∫˘Ÿú™‰ ¥˘Ë≤Ù™-¿Ÿú-æËíºÎ ÇŸ¿ËßThe‹ºÎ ÑôöËÅ Ç⁄∞¿Ë⁄“®¤ Ñ∆ || ¥˘®Ωæ Ã˘¤-í‹¡ºÎ ≤Ÿ¨ ÇúŸ≤™ŸºÎ | “§-¥˘Æ¤⁄¥éŸºÎ ∞%Bhagavad‰ —∆Ÿ´ºŸ¿ŸºÅ é‚¥Ÿé¿Å Gita || “§-⁄∆YŸºÎ ⁄“ º´—æ‰≥Æ˙-íË¿’-ÇŸYŸ {Ÿ “§-æËí-⁄∆YŸ | ⁄∆∫˘Ÿú™‰ ¥˘Ë≤Ù™-¿Ÿú-æËíºÎ ÇŸ¿Ëß‹ºÎ ÑôöËÅ Ç⁄∞¿Ë⁄“®¤ Ñ∆ || ¥˘®Ωæ Ã˘¤ æËíºÎ ÇúŸ≤™ŸºÎ | “§-¥˘Æ¤⁄¥éŸºÎ ∞%‰ —∆Ÿ´ºŸ¿ŸºÅ é‚¥Ÿé¿Å || “§-⁄∆YŸºÎ ⁄“ º´—æ‰≥Æ˙-íË¿’ ≤ Ü¥⁄Æ{Ÿ “§-æËí-⁄∆YŸ | ⁄∆∫˘Ÿú™‰ ¥˘Ë≤Ù™-¿Ÿú-æËíºÎ ÇŸ¿Ëß‹ºÎ ÑôöËÅ Ç⁄∞¿Ë⁄“®¤ Ñ∆ || ¥˘ ≥™‰ ¿Ÿú-æËíºÎ ÇúŸ≤™ŸºÎ | “§-¥The˘Æ¤⁄¥éŸº OriginalÎ ∞%‰ —∆Ÿ´ºŸ¿ŸºÅSanskrit é‚¥Ÿé¿Å || “§-⁄∆YŸºÎ ⁄“ º´—æ‰ —ºÊ æ‰≤ Ü¥⁄Æ{Ÿ “§-æËí-⁄∆YŸ | ⁄∆∫˘Ÿú™‰ ¥˘Ë≤Ù™-¿Ÿú-æËíºÎ ÇŸ¿Ëß‹ºÎ ÑôöËÅ Ç⁄∞¿Ë⁄“®¤ Ñ “‹-º™-±∆Ÿ≥™‰ ¿Ÿú-æËíºÎ ÇúŸ≤™ŸºÎ | “§-¥˘Æ¤⁄¥éŸºand Î ∞%‰ —∆Ÿ´ºŸ¿ŸºÅ é‚¥Ÿé¿Å || “§-⁄∆YŸº Å Ç—™‹ ™—ºÊ æ‰≤ Ü¥⁄Æ{Ÿ “§-æËí-⁄∆YŸ | ⁄∆∫˘Ÿú™‰ ¥˘Ë≤Ù™-¿Ÿú-æËíºÎ ÇŸ¿Ëß‹ºÎ ÑôöËÅ Ç⁄∞¿ Ÿ ∏“‹-º™-±∆Ÿ≥™‰ ¿Ÿú-æËíºÎ ÇúŸ≤™ŸºÎ | “§-¥˘Æ¤⁄¥éŸºÎ ∞%‰ —∆Ÿ´ºŸ¿ŸºÅ é‚¥Ÿé¿Å || “§- An English Translation ≤Ÿ¨Ÿæ -

2.Hindu Websites Sorted Category Wise

Hindu Websites sorted Category wise Sl. No. Broad catergory Website Address Description Reference Country 1 Archaelogy http://aryaculture.tripod.com/vedicdharma/id10. India's Cultural Link with Ancient Mexico html America 2 Archaelogy http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Harappa Harappa Civilisation India 3 Archaelogy http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Indus_Valley_Civil Indus Valley Civilisation India ization 4 Archaelogy http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kiradu_temples Kiradu Barmer Temples India 5 Archaelogy http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mohenjo_Daro Mohenjo_Daro Civilisation India 6 Archaelogy http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Nalanda Nalanda University India 7 Archaelogy http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Taxila Takshashila University Pakistan 8 Archaelogy http://selians.blogspot.in/2010/01/ganesha- Ganesha, ‘lingga yoni’ found at newly Indonesia lingga-yoni-found-at-newly.html discovered site 9 Archaelogy http://vedicarcheologicaldiscoveries.wordpress.c Ancient Idol of Lord Vishnu found Russia om/2012/05/27/ancient-idol-of-lord-vishnu- during excavation in an old village in found-during-excavation-in-an-old-village-in- Russia’s Volga Region russias-volga-region/ 10 Archaelogy http://vedicarcheologicaldiscoveries.wordpress.c Mahendraparvata, 1,200-Year-Old Cambodia om/2013/06/15/mahendraparvata-1200-year- Lost Medieval City In Cambodia, old-lost-medieval-city-in-cambodia-unearthed- Unearthed By Archaeologists 11 Archaelogy http://wikimapia.org/7359843/Takshashila- Takshashila University Pakistan Taxila 12 Archaelogy http://www.agamahindu.com/vietnam-hindu- Vietnam -

Part 1: the Beginning of Mahabharat

Mahabharat Story Credits: Internet sources, Amar Chitra Katha Part 1: The Beginning of Mahabharat The story of Mahabharata starts with King Dushyant, a powerful ruler of ancient India. Dushyanta married Shakuntala, the foster-daughter of sage Kanva. Shakuntala was born to Menaka, a nymph of Indra's court, from sage Vishwamitra, who secretly fell in love with her. Shakuntala gave birth to a worthy son Bharata, who grew up to be fearless and strong. He ruled for many years and was the founder of the Kuru dynasty. Unfortunately, things did not go well after the death of Bharata and his large empire was reduced to a kingdom of medium size with its capital Hastinapur. Mahabharata means the story of the descendents of Bharata. The regular saga of the epic of the Mahabharata, however, starts with king Shantanu. Shantanu lived in Hastinapur and was known for his valor and wisdom. One day he went out hunting to a nearby forest. Reaching the bank of the river Ganges (Ganga), he was startled to see an indescribably charming damsel appearing out of the water and then walking on its surface. Her grace and divine beauty struck Shantanu at the very first sight and he was completely spellbound. When the king inquired who she was, the maiden curtly asked, "Why are you asking me that?" King Shantanu admitted "Having been captivated by your loveliness, I, Shantanu, king of Hastinapur, have decided to marry you." "I can accept your proposal provided that you are ready to abide by my two conditions" argued the maiden. "What are they?" anxiously asked the king. -

1.Hindu Websites Sorted Alphabetically

Hindu Websites sorted Alphabetically Sl. No. Website Address Description Broad catergory Reference Country 1 http://18shaktipeetasofdevi.blogspot.com/ 18 Shakti Peethas Goddess India 2 http://18shaktipeetasofdevi.blogspot.in/ 18 Shakti Peethas Goddess India 3 http://199.59.148.11/Gurudev_English Swami Ramakrishnanada Leader- Spiritual India 4 http://330milliongods.blogspot.in/ A Bouquet of Rose Flowers to My Lord India Lord Ganesh Ji 5 http://41.212.34.21/ The Hindu Council of Kenya (HCK) Organisation Kenya 6 http://63nayanar.blogspot.in/ 63 Nayanar Lord India 7 http://75.126.84.8/ayurveda/ Jiva Institute Ayurveda India 8 http://8000drumsoftheprophecy.org/ ISKCON Payers Bhajan Brazil 9 http://aalayam.co.nz/ Ayalam NZ Hindu Temple Society Organisation New Zealand 10 http://aalayamkanden.blogspot.com/2010/11/s Sri Lakshmi Kubera Temple, Temple India ri-lakshmi-kubera-temple.html Rathinamangalam 11 http://aalayamkanden.blogspot.in/ Journey of lesser known temples in Temples Database India India 12 http://aalayamkanden.blogspot.in/2010/10/bra Brahmapureeswarar Temple, Temple India hmapureeswarar-temple-tirupattur.html Tirupattur 13 http://accidentalhindu.blogspot.in/ Hinduism Information Information Trinidad & Tobago 14 http://acharya.iitm.ac.in/sanskrit/tutor.php Acharya Learn Sanskrit through self Sanskrit Education India study 15 http://acharyakishorekunal.blogspot.in/ Acharya Kishore Kunal, Bihar Information India Mahavir Mandir Trust (BMMT) 16 http://acm.org.sg/resource_docs/214_Ramayan An international Conference on Conference Singapore -

Chapters 152 – 154(PDF)

1 Ādi (225) 2 Sabhā (72) 3 Āranyaka (299) Rishi Vaishampayana said, 4 Virāta (67) vaiśampāyana uvāca 5 Udyoga (197) 6 Bhīshma (117) 7 Drona (173) 8 Karna (69) Bhishma’s Death 9 Shālya (64) Anushāsana Parva 10 Sauptika (18) 11 Strī Parva (27) Chapters 152-154 12 Shānti (353) 13 Anushāsana – 154 chapters 14 Ashvamedhika (96) 15 Āshramavāsika (47) 16 Mausala (9) 17 Mahāprasthānika (3) Swami Tadatmananda 18 Svargārohana (5) Arsha Bodha Center Then Bhishma fell silent, unto Bhishma, laying on a bed of arrows, tūṣṇīm-bhūte tadā bhīṣme nṛpaṁ śayānaṁ gāṅgeyam | || looking like a picture on canvas, then said these words: paṭe citram ivārpitam idam āha vacas tadā (152.1) while meditating for a long time. muhūrtam iva ca dhyātvā | Vyasa, the son of Satyavati ... vyāsaḥ satyavatī-sutaḥ Rishi Vyasa said, O Bhishma, restored to his senses vyāsa uvāca rājan prakṛtim āpannaḥ | is Yudhishthira, king of the Kurus. kuru-rājo yudhiṣṭhiraḥ For him to return to the city, tam imaṁ pura-yānāya || you should give permission. tvam anujñātum arhasi (152.2,3) Bhishma said, O Yudhishthira, please return to the city, bhīṣma uvāca praviśasva puraṁ rājan | release the tension from your mind, vyetu te mānaso jvaraḥ appease all people of the kingdom, rañjayasva prajāḥ sarvāḥ || and bring peace to the hearts of all. prakṛtīḥ parisāntvaya (152.5,8) O Yudhishthira, support You should come back anu tvāṁ tāta jīvantu āgantavyaṁ ca bhavatā | | your friends and wellwishers at the time, O Yudhishthira, mitrāṇi suhṛdas tathā samaye mama pārthiva like a tree in a sacred place when the sun stops going South caitya-sthāne sthitaṁ vṛkṣaṁ vinivṛtte dinakare || || bearing fruit on which birds live. -

Entertainment Worldwelcome to Entertainment World HERE You

Welcome To Entertainment WorldWelcome To Entertainment World HERE You Can get all the Latest Movies, Songs, Games And Softwares for free.English Movies English Movies In Hindi Hindi Movies Hindi Songs PC Softwares PC Games Punjabi Songs Disclaimer Search Stuffs On This Blog Latest Hindi ( Bollywood ) Songs : Delhi 6 Billu Barber 42 Kms Jugaad Aasma Luck By Chance Dev. D Jumbo Victory Slumdog Millionaire Raaz The Mystery Continues... Chandni Chowk To China Wafaa Ghajini Meerabai Not Out Sorry Bhai Khallballi Dil Kabaddi Ek Vivaah Aisa Bhi Rab Ne Bana Di Jodi Yuvvraaj Kaashh Mere Hote My friends COLLECTOR ZONE Groovy Corner Masti Zone Movies Zone Categories Animated Movies Applications Bollywood Movies Christmas Dvd Ripped Movies DvdRipped Movies Ebooks English Movie's English Movie's In Hindi English Movies Fun Corner Hindi Movies Hindi Song's Hollywood Movies Masti Cafe Special Mobile Stuff NEWS Old Hindi Movies PC Games PC Software's Punjabi Movies Punjabi Song's Soundtracks Telugu Movies Telugu Songs Tools And Tips Trailer Video Song's Chat Here!!!!!!! Advertise on www.masti.tk Powered By AdBrite But Sponsered By Manveer Singh Your Ad Here HAPPY NEW YEAR HAPPY NEW YEAR 2009 HAPPY NEW YEAR 2009 TO ALL MY SITE VISITORS Labels: Greetings, Masti Cafe Special, NEWS HAPPY NEW YEAR HAPPY NEW YEAR 2009 HAPPY NEW YEAR 2009 TO ALL MY SITE VISITORS Labels: Greetings, Masti Cafe Special, NEWS Lucky by chance 2008HQ320Kbps Original CDRip Music Director : Shankar Ehsaan Loy Cast : Farhan Akhtar , Konkona Sen Sharma Label: Big Music 01.Yeh Zindagi -

List of Employees in Bank of Maharashtra As of 31.07.2020

LIST OF EMPLOYEES IN BANK OF MAHARASHTRA AS OF 31.07.2020 PFNO NAME BRANCH_NAME / ZONE_NAME CADRE GROSS PEN_OPT 12581 HANAMSHET SUNIL KAMALAKANT HEAD OFFICE GENERAL MANAGER 170551.22 PENSION 13840 MAHESH G. MAHABALESHWARKAR HEAD OFFICE GENERAL MANAGER 182402.87 PENSION 14227 NADENDLA RAMBABU HEAD OFFICE GENERAL MANAGER 170551.22 PENSION 14680 DATAR PRAMOD RAMCHANDRA HEAD OFFICE GENERAL MANAGER 182116.67 PENSION 16436 KABRA MAHENDRAKUMAR AMARCHAND AURANGABAD ZONE GENERAL MANAGER 168872.35 PENSION 16772 KOLHATKAR VALLABH DAMODAR HEAD OFFICE GENERAL MANAGER 182402.87 PENSION 16860 KHATAWKAR PRASHANT RAMAKANT HEAD OFFICE GENERAL MANAGER 183517.13 PENSION 18018 DESHPANDE NITYANAND SADASHIV NASIK ZONE GENERAL MANAGER 169370.75 PENSION 18348 CHITRA SHIRISH DATAR DELHI ZONE GENERAL MANAGER 166230.23 PENSION 20620 KAMBLE VIJAYKUMAR NIVRUTTI MUMBAI CITY ZONE GENERAL MANAGER 169331.55 PENSION 20933 N MUNI RAJU HEAD OFFICE GENERAL MANAGER 172329.83 PENSION 21350 UNNAM RAGHAVENDRA RAO KOLKATA ZONE GENERAL MANAGER 170551.22 PENSION 21519 VIVEK BHASKARRAO GHATE STRESSED ASSET MANAGEMENT BRANCH GENERAL MANAGER 160728.37 PENSION 21571 SANJAY RUDRA HEAD OFFICE GENERAL MANAGER 182204.27 PENSION 22663 VIJAY PRAKASH SRIVASTAVA HEAD OFFICE GENERAL MANAGER 179765.67 PENSION 11631 BAJPAI SUDHIR DEVICHARAN HEAD OFFICE DEPUTY GENERAL MANAGER 153798.27 PENSION 13067 KURUP SUBHASH MADHAVAN FORT MUMBAI DEPUTY GENERAL MANAGER 153798.27 PENSION 13095 JAT SUBHASHSINGH HEAD OFFICE DEPUTY GENERAL MANAGER 153798.27 PENSION 13573 K. ARVIND SHENOY HEAD OFFICE DEPUTY GENERAL MANAGER 164483.52 PENSION 13825 WAGHCHAVARE N.A. PUNE CITY ZONE DEPUTY GENERAL MANAGER 155576.88 PENSION 13962 BANSWANI MAHESH CHOITHRAM HEAD OFFICE DEPUTY GENERAL MANAGER 153798.27 PENSION 14359 DAS ALOKKUMAR SUDHIR Retail Assets Branch, New Delhi. -

Hindu Websites Sorted Alphabetically Sl

Hindu Websites sorted Alphabetically Sl. No. Website Address Description Broad catergory Reference Country 1 http://18shaktipeetasofdevi.blogspot.com/ 18 Shakti Peethas Goddess India 2 http://18shaktipeetasofdevi.blogspot.in/ 18 Shakti Peethas Goddess India 3 http://199.59.148.11/Gurudev_English Swami Ramakrishnanada Leader- Spiritual India 4 http://330milliongods.blogspot.in/ A Bouquet of Rose Flowers to My Lord India Lord Ganesh Ji 5 http://41.212.34.21/ The Hindu Council of Kenya (HCK) Organisation Kenya 6 http://63nayanar.blogspot.in/ 63 Nayanar Lord India 7 http://75.126.84.8/ayurveda/ Jiva Institute Ayurveda India 8 http://8000drumsoftheprophecy.org/ ISKCON Payers Bhajan Brazil 9 http://aalayam.co.nz/ Ayalam NZ Hindu Temple Society Organisation New Zealand 10 http://aalayamkanden.blogspot.com/2010/11/s Sri Lakshmi Kubera Temple, Temple India ri-lakshmi-kubera-temple.html Rathinamangalam 11 http://aalayamkanden.blogspot.in/ Journey of lesser known temples in Temples Database India India 12 http://aalayamkanden.blogspot.in/2010/10/bra Brahmapureeswarar Temple, Temple India hmapureeswarar-temple-tirupattur.html Tirupattur 13 http://accidentalhindu.blogspot.in/ Hinduism Information Information Trinidad & Tobago 14 http://acharya.iitm.ac.in/sanskrit/tutor.php Acharya Learn Sanskrit through self Sanskrit Education India study 15 http://acharyakishorekunal.blogspot.in/ Acharya Kishore Kunal, Bihar Information India Mahavir Mandir Trust (BMMT) 16 http://acm.org.sg/resource_docs/214_Ramayan An international Conference on Conference Singapore -

Contribution of Ancient Indian Literature to International Law - a Case Study of the Ramayana and the Mahabharata

Contribution Of Ancient Indian Literature To International Law - A Case Study Of The Ramayana And The Mahabharata Dissertation Submitted to Stella Maris College (Autonomous), Chennai In partial fulfillment of the Degree of Masters of Arts In International Studies By V.Sanjanaa 16/PISA/519 Department of International Studies Stella Maris College (Autonomous), Chennai Chennai 600086 March 2018 Contribution Of Ancient Indian Literature To International Law - A Case Study Of The Ramayana And The Mahabharata Dissertation Submitted to Stella Maris College (Autonomous), Chennai In partial fulfillment of the Degree of Masters of Arts In International Studies By V.Sanjanaa 16/PISA/519 Department of International Studies Stella Maris College (Autonomous), Chennai Chennai 600086 March 2018 !i DECLARATION I, V.Sanjanaa, declare that the dissertation “Contribution Of Ancient Indian Literature To International Law- A Case Study Of The Ramayana And The Mahabharata” is completed by me in partial fulfillment for the Degree of Master of International Studies. It is a record of the dissertation done by me during the year 2017-2018 and this dissertation has not formed the basis for any Degree, Diploma, Associateship, Fellowship or similar other titles. Date: Place: Chennai (V.Sanjanaa) Name of the Candidate & Signature Counter Signed Ms. Aarti S. MA(His), MA(Intl.Relns.), B.L.,P.G.D.I.B.L.), NET Head Dept of International Studies, Stella Maris College (Autonomous), Chennai- 600086 !ii CERTIFICATE OF THE SUPERVISOR Ms. Aarti S. MA(His), MA(Intl.Relns.), B.L.,P.G.D.I.B.L.), NET Head Dept of International Studies, Stella Maris College (Autonomous), Chennai- 600086 This is to certify that the dissertation “Contribution Of Ancient Indian Literature To International Law- A Case Study Of The Ramayana And The Mahabharata” is a record of the dissertation work done by V.Sanjanaa, a full time M.A.