Johnny Gumb's Diary of His Return Visit to Mochudi in 2003 Edited By

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Scramble for Land Between the Barokologadi Community and Hermannsburg Missionaries

The Scramble for Land between the Barokologadi Community and Hermannsburg Missionaries Victor MS Molobi https://orcid.org/0000-0001-7824-1048 University of South Africa [email protected] Abstract This article investigates the land claim of the Barokologadi of Melorane, with their long history of disadvantages in the land of their forefathers. The sources of such disadvantages are traceable way back to tribal wars (known as “difaqane”) in South Africa. At first, people were forced to retreat temporarily to a safer site when the wars were in progress. On their return, the Hermannsburg missionaries came to serve in Melorane, benefiting from the land provided by the Kgosi. Later the government of the time expropriated that land. What was the significance of this land? The experience of Melorane was not necessarily unique; it was actually a common practice aimed at acquiring land from rural communities. This article is an attempt to present the facts of that event. There were, however, later interruptions, such as when the Hermannsburg Mission Church became part of the Evangelical Lutheran Church of Southern Africa (ELCSA). Keywords: land claim; church land; Barokologadi; missionary movement; Hermannsburg; Melorane; Lutheran Introduction Melorane is the area that includes the southern part of Madikwe Game Park in the North West Province, with the village situated inside the park. The community of Melorane is known as the Barokologadi of Maotwe, which was forcibly removed in 1950. Morokologadi is a porcupine, which is a totem of the Barokologadi community. The community received their land back on 6 July 2007 through the National Department of Land Affairs. -

Botswana Environment Statistics Water Digest 2018

Botswana Environment Statistics Water Digest 2018 Private Bag 0024 Gaborone TOLL FREE NUMBER: 0800600200 Tel: ( +267) 367 1300 Fax: ( +267) 395 2201 E-mail: [email protected] Website: http://www.statsbots.org.bw Published by STATISTICS BOTSWANA Private Bag 0024, Gaborone Phone: 3671300 Fax: 3952201 Email: [email protected] Website: www.statsbots.org.bw Contact Unit: Environment Statistics Unit Phone: 367 1300 ISBN: 978-99968-482-3-0 (e-book) Copyright © Statistics Botswana 2020 No part of this information shall be reproduced, stored in a Retrieval system, or even transmitted in any form or by any means, whether electronically, mechanically, photocopying or otherwise, without the prior permission of Statistics Botswana. BOTSWANA ENVIRONMENT STATISTICS WATER DIGEST 2018 Statistics Botswana PREFACE This is Statistics Botswana’s annual Botswana Environment Statistics: Water Digest. It is the first solely water statistics annual digest. This Digest will provide data for use by decision-makers in water management and development and provide tools for the monitoring of trends in water statistics. The indicators in this report cover data on dam levels, water production, billed water consumption, non-revenue water, and water supplied to mines. It is envisaged that coverage of indicators will be expanded as more data becomes available. International standards and guidelines were followed in the compilation of this report. The United Nations Framework for the Development of Environment Statistics (UNFDES) and the United Nations International Recommendations for Water Statistics were particularly useful guidelines. The data collected herein will feed into the UN System of Environmental Economic Accounting (SEEA) for water and hence facilitate an informed management of water resources. -

Populated Printable COP 2009 Botswana Generated 9/28/2009 12:01:26 AM

Populated Printable COP 2009 Botswana Generated 9/28/2009 12:01:26 AM ***pages: 415*** Botswana Page 1 Table 1: Overview Executive Summary None uploaded. Country Program Strategic Overview Will you be submitting changes to your country's 5-Year Strategy this year? If so, please briefly describe the changes you will be submitting. X Yes No Description: test Ambassador Letter File Name Content Type Date Uploaded Description Uploaded By Letter from Ambassador application/pdf 11/14/2008 TSukalac Nolan.pdf Country Contacts Contact Type First Name Last Name Title Email PEPFAR Coordinator Thierry Roels Associate Director GAP-Botswana [email protected] DOD In-Country Contact Chris Wyatt Chief, Office of Security [email protected] Cooperation HHS/CDC In-Country Contact Thierry Roels Associate Director GAP-Botswana [email protected] Peace Corps In-Country Peggy McClure Director [email protected] Contact USAID In-Country Contact Joan LaRosa USAID Director [email protected] U.S. Embassy In-Country Phillip Druin DCM [email protected] Contact Global Fund In-Country Batho C Molomo Coordinator of NACA [email protected] Representative Global Fund What is the planned funding for Global Fund Technical Assistance in FY 2009? $0 Does the USG assist GFATM proposal writing? Yes Does the USG participate on the CCM? Yes Generated 9/28/2009 12:01:26 AM ***pages: 415*** Botswana Page 2 Table 2: Prevention, Care, and Treatment Targets 2.1 Targets for Reporting Period Ending September 30, 2009 National 2-7-10 USG USG Upstream USG Total Target Downstream (Indirect) -

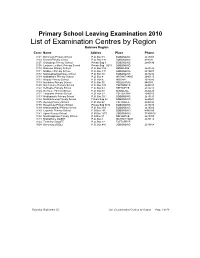

List of Examination Centres by Region Bobirwa Region Centr Name Addres Place Phone 0101 Bobonong Primary School P.O

Primary School Leaving Examination 2010 List of Examination Centres by Region Bobirwa Region Centr Name Addres Place Phone 0101 Bobonong Primary School P.O. Box 48 BOBONONG 2619207 0103 Borotsi Primary School P.O. Box 136 BOBONONG 819208 0107 Gobojango Primary School Private Bag 8 BOBONONG 2645436 0108 Lentswe-Le-Moriti Primary School Private Bag 0019 BOBONONG 0110 Mabolwe Primary School P.O. Box 182 SEMOLALE 2645422 0111 Madikwe Primary School P.O. Box 131 BOBONONG 2619221 0112 Mafetsakgang primary school P.O. Box 46 BOBONONG 2619232 0114 Mathathane Primary School P.O. Box 4 MATHATHANE 2645110 0117 Mogapi Primary School P.O. Box 6 MOGAPI 2618545 0119 Molalatau Primary School P.O. Box 50 MOLALATAU 845374 0120 Moletemane Primary School P.O. Box 176 TSETSEBYE 2646035 0123 Sefhophe Primary School P.O. Box 41 SEFHOPHE 2618210 0124 Semolale Primary School P.O. Box 10 SEMOLALE 2645422 0131 Tsetsejwe Primary School P.O. Box 33 TSETSEJWE 2646103 0133 Modisaotsile Primary School P.O. Box 591 BOBONONG 2619123 0134 Motlhabaneng Primary School Private Bag 20 BOBONONG 2645541 0135 Busang Primary School P.O. Box 47 TSETSEBJE 2646144 0138 Rasetimela Primary School Private Bag 0014 BOBONONG 2619485 0139 Mabumahibidu Primary School P.O. Box 168 BOBONONG 2619040 0140 Lepokole Primary School P O Box 148 BOBONONG 4900035 0141 Agosi Primary School P O Box 1673 BOBONONG 71868614 0142 Motsholapheko Primary School P O Box 37 SEFHOPHE 2618305 0143 Mathathane DOSET P.O. Box 4 MATHATHANE 2645110 0144 Tsetsebye DOSET P.O. Box 33 TSETSEBYE 3024 Bobonong DOSET P.O. Box 483 BOBONONG 2619164 Saturday, September 25, List of Examination Centres by Region Page 1 of 39 Boteti Region Centr Name Addres Place Phone 0201 Adult Education Private Bag 1 ORAPA 0202 Baipidi Primary School P.O. -

The Parliamentary Constituency Offices

REPUBLIC OF BOTSWANA THE PARLIAMENTARY CONSTITUENCY OFFICES Parliament of Botswana P O Box 240 Gaborone Tel: 3616800 Fax: 3913103 Toll Free; 0800 600 927 e - mail: [email protected] www.parliament.gov.bw Introduction Mmathethe-Molapowabojang Mochudi East Mochudi West P O Box 101 Mmathethe P O Box 2397 Mochudi P O Box 201951 Ntshinoge Representative democracy can only function effectively if the Members of Tel: 5400251 Fax: 5400080 Tel: 5749411 Fax: 5749989 Tel: 5777084 Fax: 57777943 Parliament are accessible, responsive and accountable to their constituents. Mogoditshane Molepolole North Molepolole South The mandate of a Constituency Office is to act as an extension of Parliament P/Bag 008 Mogoditshane P O Box 449 Molepolole P O Box 3573 Molepolole at constituency level. They exist to play this very important role of bringing Tel: 3915826 Fax: 3165803 Tel: 5921099 Fax: 5920074 Tel: 3931785 Fax: 3931785 Parliament and Members of Parliament close to the communities they serve. Moshupa-Manyana Nata-Gweta Ngami A constituency office is a Parliamentary office located at the headquarters of P O Box 1105 Moshupa P/Bag 27 Sowa Town P/Bag 2 Sehithwa Tel: 5448140 Fax: 5448139 Tel: 6213756 Fax: 6213240 Tel: 6872105/123 each constituency for use by a Member of Parliament (MP) to carry out his or Fax: 6872106 her Parliamentary work in the constituency. It is a formal and politically neutral Nkange Okavango Palapye place where a Member of Parliament and constituents can meet and discuss P/Bag 3 Tutume P O Box 69 Shakawe P O Box 10582 Palapye developmental issues. Tel: 2987717 Fax: 2987293 Tel: 6875257/230 Tel: 4923475 Fax: 4924231 Fax: 6875258 The offices must be treated strictly as Parliamentary offices and must therefore Ramotswa Sefhare-Ramokgonami Selibe Phikwe East be used for Parliamentary business and not political party business. -

Department of Road Transport and Safety Offices

DEPARTMENT OF ROAD TRANSPORT AND SAFETY OFFICES AND SERVICES MOLEPOLOLE • Registration & Licensing of vehicles and drivers • Driver Examination (Theory & Practical Tests) • Transport Inspectorate Tel: 5920148 Fax: 5910620 P/Bag 52 Molepolole Next to Molepolole Police MOCHUDI • Registration & Licensing of vehicles and drivers • Driver Examination (Theory & Practical Tests) • Transport Inspectorate P/Bag 36 Mochudi Tel : 5777127 Fax : 5748542 White House GABORONE Headquarters BBS Mall Plot no 53796 Tshomarelo House (Botswana Savings Bank) 1st, 2nd &3rd Floor Corner Lekgarapa/Letswai Road •Registration & Licensing of vehicles and drivers •Road safety (Public Education) Tel: 3688600/62 Fax : Fax: 3904067 P/Bag 0054 Gaborone GABORONE VTS – MARUAPULA • Registration & Licensing of vehicles and drivers • Driver Examination (Theory & Practical Tests) • Vehicle Examination Tel: 3912674/2259 P/Bag BR 318 B/Hurst Near Roads Training & Roads Maintenance behind Maruapula Flats GABORONE II – FAIRGROUNDS • Registration & Licensing of vehicles and drivers • Driver Examination : Theory Tel: 3190214/3911540/3911994 Fax : P/Bag 0054 Gaborone GABORONE - OLD SUPPLIES • Registration & Licensing of vehicles and drivers • Transport Permits • Transport Inspectorate Tel: 3905050 Fax :3932671 P/Bag 0054 Gaborone Plot 1221, Along Nkrumah Road, Near Botswana Power Corporation CHILDREN TRAFFIC SCHOOL •Road Safety Promotion for children only Tel: 3161851 P/Bag BR 318 B/Hurst RAMOTSWA •Registration & Licensing of vehicles and drivers •Driver Examination (Theory & Practical -

Botswana Semiology Research Centre Project Seismic Stations In

BOTSWANA SEISMOLOGICAL NETWORK ( BSN) STATIONS 19°0'0"E 20°0'0"E 21°0'0"E 22°0'0"E 23°0'0"E 24°0'0"E 25°0'0"E 26°0'0"E 27°0'0"E 28°0'0"E 29°0'0"E 30°0'0"E 1 S 7 " ° 0 0 ' ' 0 0 ° " 7 S 1 KSANE Kasane ! !Kazungula Kasane Forest ReserveLeshomo 1 S Ngoma Bridge ! 8 " ! ° 0 0 ' # !Mabele * . MasuzweSatau ! ! ' 0 ! ! Litaba 0 ° Liamb!ezi Xamshiko Musukub!ili Ivuvwe " 8 ! ! ! !Seriba Kasane Forest Reserve Extension S 1 !Shishikola Siabisso ! ! Ka!taba Safari Camp ! Kachikau ! ! ! ! ! ! Chobe Forest Reserve ! !! ! Karee ! ! ! ! ! Safari Camp Dibejam!a ! ! !! ! ! ! ! X!!AUD! M Kazuma Forest Reserve ! ShongoshongoDugamchaRwelyeHau!xa Marunga Xhauga Safari Camp ! !SLIND Chobe National Park ! Kudixama Diniva Xumoxu Xanekwa Savute ! Mah!orameno! ! ! ! Safari Camp ! Maikaelelo Foreset Reserve Do!betsha ! ! Dibebe Tjiponga Ncamaser!e Hamandozi ! Quecha ! Duma BTLPN ! #Kwiima XanekobaSepupa Khw!a CHOBE DISTRICT *! !! ! Manga !! Mampi ! ! ! Kangara # ! * Gunitsuga!Njova Wazemi ! ! G!unitsuga ! Wazemi !Seronga! !Kaborothoa ! 1 S Sibuyu Forest Reserve 9 " Njou # ° 0 * ! 0 ' !Nxaunxau Esha 12 ' 0 Zara ! ! 0 ° ! ! ! " 9 ! S 1 ! Mababe Quru!be ! ! Esha 1GMARE Xorotsaa ! Gumare ! ! Thale CheracherahaQNGWA ! ! GcangwaKaruwe Danega ! ! Gqose ! DobeQabi *# ! ! ! ! Bate !Mahito Qubi !Mahopa ! Nokaneng # ! Mochabana Shukumukwa * ! ! Nxabe NGAMILAND DISTRICT Sorob!e ! XurueeHabu Sakapane Nxai National Nark !! ! Sepako Caecae 2 ! ! S 0 " Konde Ncwima ° 0 ! MAUN 0 ' ! ! ' 0 Ntabi Tshokatshaa ! 0 ° ! " 0 PHDHD Maposa Mmanxotai S Kaore ! ! Maitengwe 2 ! Tsau Segoro -

Kgatleng SUB District

Kgatleng SUB District VOL 5.0 KGATLENG SUB DISTRICT Population and Housing Census 2011 Selected Indicators for Villages and Localities ii i Population and Housing Census 2011 [ Selected indicators ] Kgatleng Sub District Population and Housing Census 2011 [Selected Indicators] Kgatleng Sub District 3 Table of Contents Kgatleng Sub District Population And Housing Census 2011: Selected Indicators For Villages And Localities Preface 3 VOL 5,0 1.0 Background and Commentary 6 1.1 Background to the Report 6 Published by 1.2 Importance of the Report 6 STATISTICS BOTSWANA Private Bag 0024, Gaborone 2.0 Population Distribution 6 Phone: (267)3671300, 3.0 Population Age Structure 6 Fax: (267) 3952201 Email: [email protected] 3.1 The Youth 7 Website: www.cso.gov.bw/cso 3.2 The Elderly 7 4.0 Annual Growth Rate 7 5.0 Household Size 7 COPYRIGHT RESERVED 6.0 Marital Status 8 7.0 Religion 8 Extracts may be published if source is duly acknowledged 8.0 Disability 9 9.0 Employment and Unemployment 9 10.0 Literacy 10 ISBN: 978-99968-429-7-9 11.0 Orphan-hood 10 12.0 Access to Drinking Water and Sanitation 10 12.1 Access to Portable Water 10 12.2 Access to Sanitation 11 13.0 Energy 11 13.1 Source of Fuel for Heating 11 13.2 Source of Fuel for Lighting 12 13.3 Source of Fuel for Cooking 12 14.0 Projected Population 2011 – 2026 13 Annexes 14 iii Population and Housing Census 2011 [ Selected indicators ] Kgatleng Sub District Population and Housing Census 2011 [Selected Indicators] Kgatleng Sub District 1 FIGURE 1: MAP OF KATLENG DISTRICT Preface This report follows our strategic resolve to disaggregate the 2011 Population and Housing Census report, and many of our statistical outputs, to cater for specific data needs of users. -

2011 Population & Housing Census Preliminary Results Brief

2011 Population & Housing Census Preliminary Results Brief For further details contact Census Office, Private Bag 0024 Gaborone: Tel 3188500; Fax 3188610 1. Botswana Population at 2 Million Botswana’s population has reached the 2 million mark. Preliminary results show that there were 2 038 228 persons enumerated in Botswana during the 2011 Population and Housing Census, compared with 1 680 863 enumerated in 2001. Suffice to note that this is the de-facto population – persons enumerated where they were found during enumeration. 2. General Comments on the Results 2.1 Population Growth The annual population growth rate 1 between 2001 and 2011 is 1.9 percent. This gives further evidence to the effect that Botswana’s population continues to increase at diminishing growth rates. Suffice to note that inter-census annual population growth rates for decennial censuses held from 1971 to 2001 were 4.6, 3.5 and 2.4 percent respectively. A close analysis of the results shows that it has taken 28 years for Botswana’s population to increase by one million. At the current rate and furthermore, with the current conditions 2 prevailing, it would take 23 years for the population to increase by another million - to reach 3 million. Marked differences are visible in district population annual growths, with estimated zero 3 growth for Selebi-Phikwe and Lobatse and a rate of over 4 percent per annum for South East District. Most district growth rates hover around 2 percent per annum. High growth rates in Kweneng and South East Districts have been observed, due largely to very high growth rates of villages within the proximity of Gaborone. -

Nubm 1 9 6 6

REGISTERED WITH THE DIRECTOR OF POSTS AND TELEGRAPHS AS A NEWSPAPER REGISTERED WITH THE DIRECTOR OF POSTS AND TELEGRAPHS AS A NEWSPAPER Volume IV No. 5 Organ of the Bechuanaland Democratic Party JULY, 1966 Local Government Elections: A Post-mortem THE Local Government Elections, the first in self-governing Bechuanaland, soon to be called Botswana, have come and passed, and their results must necessarily be assessed against a number of circumstances, coming as they do a year only after the smashing victory of the Bechuanaland Democratic Party at the first national elections in March 1965. DISCOMFITURE OF THE OPPOSITION AT NOMINATION As far as the opposition parties were concerned their defeat was decided at the nomination on the 23rd May. In spite of the much publicised coalition or election pact between the Pechuanaland People's Party and the Independence Party, the former could only field forty-nine (49) candidates for the total possible of 165 seats while the latter managed only twenty-one (21). The newly-launched Botswana National Front, which had waged a war of nerves by trying to make the country believe they had captured all the followers of the Democratic Party, was able to field only seven, although it is possible that two or three so-called independents in Lobatsi were Front supporters who did not have the guts to stand under their proper colours. The nomination results were that 82 of the B.D.P. candidates, and one Independent were returned unopposed, about 50% of the total possible seats. The election contest was for the balance of 82 seats, and the final result was as follows: Bechuanaland Democratic Party 136 Bechuanaland People's Party 21 Bechuanaland Independence Party 5 Independents 3 Botswana National Front Nil 165 VOTES CAST ACCORDING TO PARTIES Following are the totals of votes cast according to parties for the 82 contested seats: B.D.P.: 30,934; B.P.P.: 10,473; B.I.P.: 3,346; B.N.F.: 398; Independents: 1432; Total 46,583 (37147). -

E-Government and Democracy in Botswana: Observational and Experimental Evidence on the Effects of E-Government Usage on Political Attitudes

A Service of Leibniz-Informationszentrum econstor Wirtschaft Leibniz Information Centre Make Your Publications Visible. zbw for Economics Bante, Jana et al. Working Paper E-government and democracy in Botswana: Observational and experimental evidence on the effects of e-government usage on political attitudes Discussion Paper, No. 16/2021 Provided in Cooperation with: German Development Institute / Deutsches Institut für Entwicklungspolitik (DIE), Bonn Suggested Citation: Bante, Jana et al. (2021) : E-government and democracy in Botswana: Observational and experimental evidence on the effects of e-government usage on political attitudes, Discussion Paper, No. 16/2021, ISBN 978-3-96021-153-2, Deutsches Institut für Entwicklungspolitik (DIE), Bonn, http://dx.doi.org/10.23661/dp16.2021 This Version is available at: http://hdl.handle.net/10419/234177 Standard-Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Die Dokumente auf EconStor dürfen zu eigenen wissenschaftlichen Documents in EconStor may be saved and copied for your Zwecken und zum Privatgebrauch gespeichert und kopiert werden. personal and scholarly purposes. Sie dürfen die Dokumente nicht für öffentliche oder kommerzielle You are not to copy documents for public or commercial Zwecke vervielfältigen, öffentlich ausstellen, öffentlich zugänglich purposes, to exhibit the documents publicly, to make them machen, vertreiben oder anderweitig nutzen. publicly available on the internet, or to distribute or otherwise use the documents in public. Sofern die Verfasser die Dokumente unter Open-Content-Lizenzen (insbesondere CC-Lizenzen) zur Verfügung gestellt haben sollten, If the documents have been made available under an Open gelten abweichend von diesen Nutzungsbedingungen die in der dort Content Licence (especially Creative Commons Licences), you genannten Lizenz gewährten Nutzungsrechte. -

Geographical Names Standardization BOTSWANA GEOGRAPHICAL

SCALE 1 : 2 000 000 BOTSWANA GEOGRAPHICAL NAMES 20°0'0"E 22°0'0"E 24°0'0"E 26°0'0"E 28°0'0"E Kasane e ! ob Ch S Ngoma Bridge S " ! " 0 0 ' ' 0 0 ° Geographical Names ° ! 8 !( 8 1 ! 1 Parakarungu/ Kavimba ti Mbalakalungu ! ± n !( a Kakulwane Pan y K n Ga-Sekao/Kachikaubwe/Kachikabwe Standardization w e a L i/ n d d n o a y ba ! in m Shakawe Ngarange L ! zu ! !(Ghoha/Gcoha Gate we !(! Ng Samochema/Samochima Mpandamatenga/ This map highlights numerous places with Savute/Savuti Chobe National Park !(! Pandamatenga O Gudigwa te ! ! k Savu !( !( a ! v Nxamasere/Ncamasere a n a CHOBE DISTRICT more than one or varying names. The g Zweizwe Pan o an uiq !(! ag ! Sepupa/Sepopa Seronga M ! Savute Marsh Tsodilo !(! Gonutsuga/Gonitsuga scenario is influenced by human-centric Xau dum Nxauxau/Nxaunxau !(! ! Etsha 13 Jao! events based on governance or culture. achira Moan i e a h hw a k K g o n B Cakanaca/Xakanaka Mababe Ta ! u o N r o Moremi Wildlife Reserve Whether the place name is officially X a u ! G Gumare o d o l u OKAVANGO DELTA m m o e ! ti g Sankuyo o bestowed or adopted circumstantially, Qangwa g ! o !(! M Xaxaba/Cacaba B certain terminology in usage Nokaneng ! o r o Nxai National ! e Park n Shorobe a e k n will prevail within a society a Xaxa/Caecae/Xaixai m l e ! C u a n !( a d m a e a a b S c b K h i S " a " e a u T z 0 d ih n D 0 ' u ' m w NGAMILAND DISTRICT y ! Nxai Pan 0 m Tsokotshaa/Tsokatshaa 0 Gcwihabadu C T e Maun ° r ° h e ! 0 0 Ghwihaba/ ! a !( o 2 !( i ata Mmanxotae/Manxotae 2 g Botet N ! Gcwihaba e !( ! Nxharaga/Nxaraga !(! Maitengwe