The Fastest Kid on the Block: the Marty Glickman Story

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Division I Men's Outdoor Track Championships Records Book

DIVISION I MEN’S OUTDOOR TRACK CHAMPIONSHIPS RECORDS BOOK 2020 Championship 2 History 2 All-Time Team Results 30 2020 CHAMPIONSHIP The 2020 championship was not contested due to the COVID-19 pandemic. HISTORY TEAM RESULTS (Note: No meet held in 1924.) †Indicates fraction of a point. *Unofficial champion. Year Champion Coach Points Runner-Up Points Host or Site 1921 Illinois Harry Gill 20¼ Notre Dame 16¾ Chicago 1922 California Walter Christie 28½ Penn St. 19½ Chicago 1923 Michigan Stephen Farrell 29½ Mississippi St. 16 Chicago 1925 *Stanford R.L. Templeton 31† Chicago 1926 *Southern California Dean Cromwell 27† Chicago 1927 *Illinois Harry Gill 35† Chicago 1928 Stanford R.L. Templeton 72 Ohio St. 31 Chicago 1929 Ohio St. Frank Castleman 50 Washington 42 Chicago 22 1930 Southern California Dean Cromwell 55 ⁄70 Washington 40 Chicago 1 1 1931 Southern California Dean Cromwell 77 ⁄7 Ohio St. 31 ⁄7 Chicago 1932 Indiana Billy Hayes 56 Ohio St. 49¾ Chicago 1933 LSU Bernie Moore 58 Southern California 54 Chicago 7 1934 Stanford R.L. Templeton 63 Southern California 54 ⁄20 Southern California 1935 Southern California Dean Cromwell 741/5 Ohio St. 401/5 California 1936 Southern California Dean Cromwell 103⅓ Ohio St. 73 Chicago 1937 Southern California Dean Cromwell 62 Stanford 50 California 1938 Southern California Dean Cromwell 67¾ Stanford 38 Minnesota 1939 Southern California Dean Cromwell 86 Stanford 44¾ Southern California 1940 Southern California Dean Cromwell 47 Stanford 28⅔ Minnesota 1941 Southern California Dean Cromwell 81½ Indiana 50 Stanford 1 1942 Southern California Dean Cromwell 85½ Ohio St. 44 ⁄5 Nebraska 1943 Southern California Dean Cromwell 46 California 39 Northwestern 1944 Illinois Leo Johnson 79 Notre Dame 43 Marquette 3 1945 Navy E.J. -

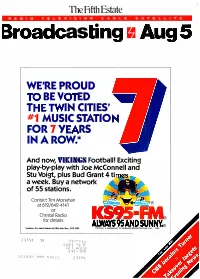

Broadcasting Ii Aug 5

The Fifth Estate R A D I O T E L E V I S I O N C A B L E S A T E L L I T E Broadcasting ii Aug 5 WE'RE PROUD TO BE VOTED THE TWIN CITIES' #1 MUSIC STATION FOR 7 YEARS IN A ROW.* And now, VIKINGS Football! Exciting play -by-play with Joe McConnell and Stu Voigt, plus Bud Grant 4 times a week. Buy a network of 55 stations. Contact Tim Monahan at 612/642 -4141 or Christal Radio for details AIWAYS 95 AND SUNNY.° 'Art:ron 1Y+ Metro Shares 6A/12M, Mon /Sun, 1979-1985 K57P-FM, A SUBSIDIARY OF HUBBARD BROADCASTING. INC. I984 SUhT OGlf ZZ T s S-lnd st-'/AON )IMM 49£21 Z IT 9.c_. I Have a Dream ... Dr. Martin Luther KingJr On January 15, 1986 Dr. King's birthday becomes a National Holiday KING... MONTGOMERY For more information contact: LEGACY OF A DREAM a Fox /Lorber Representative hour) MEMPHIS (Two Hours) (One-half TO Written produced and directed Produced by Ely Landau and Kaplan. First Richard Kaplan. Nominated for MFOXILORBER by Richrd at the Americ Film Festival. Narrated Academy Award. Introduced by by Jones. Harry Belafonte. JamcsEarl "Perhaps the most important film FOX /LORBER Associates, Inc. "This is a powerful film, a stirring documentary ever made" 432 Park Avenue South film. se who view it cannot Philadelphia Bulletin New York, N.Y. 10016 fail to be moved." Film News Telephone: (212) 686 -6777 Presented by The Dr.Martin Luther KingJr.Foundation in association with Richard Kaplan Productions. -

2011 May Digest

May 2011 • CoSIDA digest – 2 COSIDA MAY DIGEST Marco Island Convention on the Horizon Table of Contents . CoSIDA Seeking Board of Directors Nominations .......................... 4 Supporting CoSIDA 2011 CoSIDA Convention Registration Information ........................ 6 > Convention Schedule and Featured Speakers .....................7, 9-14 • Allstate Sugar Bowl ................ 15 Jackie Joyner-Kersee to Receive Enberg Award ....................20-21 CoSIDA Award Winner Feature Stories • ASAP Sports ............................. 8 Hall of Fame - Mark Beckenbach ............................................ 25 • CBS College Sports ................. 4 Hall of Fame - Charles Bloom ................................................. 26 Hall of Fame/Warren Berg Award - Rich Herman .................... 27 • ESPN ....................................... 60 Hall of Fame - Paul Madison ................................................... 28 • Fiesta Bowl ............................. 15 Trailblazer Award - Debby Jennings ........................................ 29 25-Year Award - Brian DePasquale ......................................... 30 • Heisman Trophy ..................... 45 25-Year Award - Tom Kroeschell ............................................. 31 • Liberty Mutual ......................... 45 25-Year Award - Tom Nelson ................................................... 32 25-Year Award/Lifetime Achievement - Walt Riddle ................ 33 • Lowe’s Senior CLASS Award .. 5 Academic All-America Hall of Fame Inductees Announced.....34-37 -

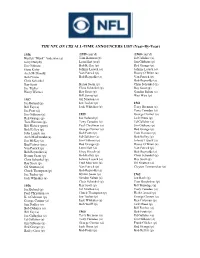

THE NFL on CBS ALL-TIME ANNOUNCERS LIST (Year-By-Year)

THE NFL ON CBS ALL-TIME ANNOUNCERS LIST (Year-By-Year) 1956 (1958 cont’d) (1960 cont’d) Hartley “Hunk” Anderson (a) Tom Harmon (p) Ed Gallaher (a) Jerry Dunphy Leon Hart (rep) Jim Gibbons (p) Jim Gibbons Bob Kelley (p) Red Grange (p) Gene Kirby Johnny Lujack (a) Johnny Lujack (a) Arch McDonald Van Patrick (p) Davey O’Brien (a) Bob Prince Bob Reynolds (a) Van Patrick (p) Chris Schenkel Bob Reynolds (a) Ray Scott Byron Saam (p) Chris Schenkel (p) Joe Tucker Chris Schenkel (p) Ray Scott (p) Harry Wismer Ray Scott (p) Gordon Soltau (a) Bill Symes (p) Wes Wise (p) 1957 Gil Stratton (a) Joe Boland (p) Joe Tucker (p) 1961 Bill Fay (a) Jack Whitaker (p) Terry Brennan (a) Joe Foss (a) Tony Canadeo (a) Jim Gibbons (p) 1959 George Connor (a) Red Grange (p) Joe Boland (p) Jack Drees (p) Tom Harmon (p) Tony Canadeo (a) Ed Gallaher (a) Bill Hickey (post) Paul Christman (a) Jim Gibbons (p) Bob Kelley (p) George Connor (a) Red Grange (p) John Lujack (a) Bob Fouts (p) Tom Harmon (p) Arch MacDonald (a) Ed Gallaher (a) Bob Kelley (p) Jim McKay (a) Jim Gibbons (p) Johnny Lujack (a) Bud Palmer (pre) Red Grange (p) Davey O’Brien (a) Van Patrick (p) Leon Hart (a) Van Patrick (p) Bob Reynolds (a) Elroy Hirsch (a) Bob Reynolds (a) Byrum Saam (p) Bob Kelley (p) Chris Schenkel (p) Chris Schenkel (p) Johnny Lujack (a) Ray Scott (p) Ray Scott (p) Fred Morrison (a) Gil Stratton (a) Gil Stratton (a) Van Patrick (p) Clayton Tonnemaker (p) Chuck Thompson (p) Bob Reynolds (a) Joe Tucker (p) Byrum Saam (p) 1962 Jack Whitaker (a) Gordon Saltau (a) Joe Bach (p) Chris Schenkel -

Handbook of Sports and Media

Job #: 106671 Author Name: Raney Title of Book: Handbook of Sports & Media ISBN #: 9780805851892 HANDBOOK OF SPORTS AND MEDIA LEA’S COMMUNICATION SERIES Jennings Bryant/Dolf Zillmann, General Editors Selected titles in Communication Theory and Methodology subseries (Jennings Bryant, series advisor) include: Berger • Planning Strategic Interaction: Attaining Goals Through Communicative Action Dennis/Wartella • American Communication Research: The Remembered History Greene • Message Production: Advances in Communication Theory Hayes • Statistical Methods for Communication Science Heath/Bryant • Human Communication Theory and Research: Concepts, Contexts, and Challenges, Second Edition Riffe/Lacy/Fico • Analyzing Media Messages: Using Quantitative Content Analysis in Research, Second Edition Salwen/Stacks • An Integrated Approach to Communication Theory and Research HANDBOOK OF SPORTS AND MEDIA Edited by Arthur A.Raney College of Communication Florida State University Jennings Bryant College of Communication & Information Sciences The University of Alabama LAWRENCE ERLBAUM ASSOCIATES, PUBLISHERS Senior Acquisitions Editor: Linda Bathgate Assistant Editor: Karin Wittig Bates Cover Design: Tomai Maridou Photo Credit: Mike Conway © 2006 This edition published in the Taylor & Francis e-Library, 2009. To purchase your own copy of this or any of Taylor & Francis or Routledge’s collection of thousands of eBooks please go to www.eBookstore.tandf.co.uk. Copyright © 2006 by Lawrence Erlbaum Associates All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form, by photostat, microform, retrieval system, or any other means, without prior written permission of the publisher. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Handbook of sports and media/edited by Arthur A.Raney, Jennings Bryant. p. cm.–(LEA’s communication series) Includes bibliographical references and index. -

NEWSLETTER Supplementingtrack & FIELD NEWS Twice Monthly

TRACKNEWSLETTER SupplementingTRACK & FIELD NEWS twice monthly. Vol. 10, No. 1 August 14, 1963 Page 1 Jordan Shuffles Team vs. Germany British See 16'10 1-4" by Pennel Hannover, Germany, July 31- ~Aug. 1- -Coach Payton Jordan London, August 3 & 5--John Pennel personally raised the shuffled his personnel around for the dual meet with West Germany, world pole vault record for the fifth time this season to 16'10¼" (he and came up with a team that carried the same two athletes that com has tied it once), as he and his U.S. teammates scored 120 points peted against the Russians in only six of the 21 events--high hurdles, to beat Great Britain by 29 points . The British athl_etes held the walk, high jump, broad jump, pole vault, and javelin throw. His U.S. Americans to 13 firsts and seven 1-2 sweeps. team proceeded to roll up 18 first places, nine 1-2 sweeps, and a The most significant U.S. defeat came in the 440 relay, as 141 to 82 triumph. the Jones boys and Peter Radford combined to run 40 . 0, which equal The closest inter-team race was in the steeplechase, where ed the world record for two turns. Again slowed by poor baton ex both Pat Traynor and Ludwig Mueller were docked in 8: 44. 4 changes, Bob Hayes gained up to five yards in the final leg but the although the U.S. athlete was given the victory. It was Traynor's U.S. still lost by a tenth. Although the American team had hoped second fastest time of the season, topped only by his mark against for a world record, the British victory was not totally unexpected. -

Nominees for the 29 Annual Sports Emmy® Awards

NOMINEES FOR THE 29 TH ANNUAL SPORTS EMMY® AWARDS ANNOUNCE AT IMG WORLD CONGRESS OF SPORTS Winners to be Honored During the April 28 th Ceremony At Frederick P. Rose Hall, Home of Jazz at Lincoln Center Frank Chirkinian To Receive Lifetime Achievement Award New York, NY – March 13th, 2008 - The National Academy of Television Arts and Sciences (NATAS) today announced the nominees for the 29 th Annual Sports Emmy ® Awards at the IMG World Congress of Sports at the St. Regis Hotel in Monarch Bay/Dana Point, California. Peter Price, CEO/President of NATAS was joined by Ross Greenberg, President of HBO Sports, Ed Goren President of Fox Sports and David Levy President of Turner Sports in making the announcement. At the 29 th Annual Sports Emmy ® Awards, winners in 30 categories including outstanding live sports special, sports documentary, studio show, play-by-play personality and studio analyst will be honored. The Awards will be given out at the prestigious Frederick P. Rose Hall, Home of Jazz at Lincoln Center located in the Time Warner Center on April 28 th , 2008 in New York City. In addition, Frank Chirkinian, referred to by many as the “Father of Televised Golf,” and winner of four Emmy ® Awards, will receive this year’s Lifetime Achievement Award that evening. Chirkinian, who spent his entire career at CBS, was given the task of figuring out how to televise the game of golf back in 1958 when the network decided golf was worth a look. Chirkinian went on to produce 38 consecutive Masters Tournament telecasts, making golf a mainstay in sports broadcasting and creating the standard against which golf telecasts are still measured. -

Versatile Fox Sports Broadcaster Kenny Albert Continues to Pair with Biggest Names in Sports

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Contact: Erik Arneson, FOX Sports Wednesday, Sept. 21, 2016 [email protected] VERSATILE FOX SPORTS BROADCASTER KENNY ALBERT CONTINUES TO PAIR WITH BIGGEST NAMES IN SPORTS Boothmates like Namath, Ewing, Palmer, Leonard ‘Enhance Broadcasts … Make My Job a Lot More Fun’ Teams with Former Cowboy and Longtime Broadcast Partner Daryl ‘Moose’ Johnston and Sideline Reporter Laura Okmin for FOX NFL in 2016 With an ever-growing roster of nearly 250 teammates (complete list below) that includes iconic names like Joe Namath, Patrick Ewing, Jim Palmer, Jeremy Roenick and “Sugar Ray” Leonard, versatile FOX Sports play-by-play announcer Kenny Albert -- the only announcer currently doing play-by-play for all four major U.S. sports (NFL, MLB, NBA and NHL) -- certainly knows the importance of preparation and chemistry. “The most important aspects of my job are definitely research and preparation,” said Albert, a second-generation broadcaster whose long-running career behind the sports microphone started in high school, and as an undergraduate at New York University in the late 1980s, he called NYU basketball games. “When the NFL season begins, it's similar to what coaches go through. If I'm not sleeping, eating or spending time with my family, I'm preparing for that Sunday's game. “And when I first work with a particular analyst, researching their career is definitely a big part of it,” Albert added. “With (Daryl Johnston) ‘Moose,’ for example, there are various anecdotes from his years with the Dallas Cowboys that pertain to our games. When I work local Knicks telecasts with Walt ‘Clyde’ Frazier on MSG, a percentage of our viewers were avid fans of Clyde during the Knicks’ championship runs in 1970 and 1973, so we weave some of those stories into the broadcasts.” As the 2016 NFL season gets underway, Albert once again teams with longtime broadcast partner Johnston, with whom he has paired for 10 seasons, sideline reporter Laura Okmin and producer Barry Landis. -

The Berlin Olympics: Sports, Anti-Semitism, and Propaganda in Nazi Germany Nathan W

Student Publications Student Scholarship Spring 2016 The Berlin Olympics: Sports, Anti-Semitism, and Propaganda in Nazi Germany Nathan W. Cody Gettysburg College Follow this and additional works at: https://cupola.gettysburg.edu/student_scholarship Part of the European History Commons, Political History Commons, Social History Commons, and the Sports Studies Commons Share feedback about the accessibility of this item. Cody, Nathan W., "The Berlin Olympics: Sports, Anti-Semitism, and Propaganda in Nazi Germany" (2016). Student Publications. 434. https://cupola.gettysburg.edu/student_scholarship/434 This is the author's version of the work. This publication appears in Gettysburg College's institutional repository by permission of the copyright owner for personal use, not for redistribution. Cupola permanent link: https://cupola.gettysburg.edu/student_scholarship/ 434 This open access student research paper is brought to you by The uC pola: Scholarship at Gettysburg College. It has been accepted for inclusion by an authorized administrator of The uC pola. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Berlin Olympics: Sports, Anti-Semitism, and Propaganda in Nazi Germany Abstract The aN zis utilized the Berlin Olympics of 1936 as anti-Semitic propaganda within their racial ideology. When the Nazis took power in 1933 they immediately sought to coordinate all aspects of German life, including sports. The process of coordination was designed to Aryanize sport by excluding non-Aryans and promoting sport as a means to prepare for military training. The 1936 Olympic Games in Berlin became the ideal platform for Hitler and the Nazis to display the physical superiority of the Aryan race. However, the exclusion of non-Aryans prompted a boycott debate that threatened Berlin’s position as host. -

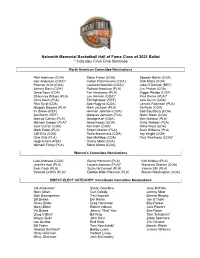

Naismith Memorial Basketball Hall of Fame Class of 2021 Ballot * Indicates First-Time Nominee

Naismith Memorial Basketball Hall of Fame Class of 2021 Ballot * Indicates First-Time Nominee North American Committee Nominations Rick Adelman (COA) Steve Fisher (COA) Speedy Morris (COA) Ken Anderson (COA)* Cotton Fitzsimmons (COA) Dick Motta (COA) Fletcher Arritt (COA) Leonard Hamilton (COA)* Jake O’Donnell (REF) Johnny Bach (COA) Richard Hamilton (PLA) Jim Phelan (COA) Gene Bess (COA) Tim Hardaway (PLA) Digger Phelps (COA) Chauncey Billups (PLA) Lou Henson (COA)* Paul Pierce (PLA)* Chris Bosh (PLA) Ed Hightower (REF) Jere Quinn (COA) Rick Byrd (COA) Bob Huggins (COA) Lamont Robinson (PLA) Muggsy Bogues (PLA) Mark Jackson (PLA) Bo Ryan (COA) Irv Brown (REF) Herman Johnson (COA) Bob Saulsbury (COA) Jim Burch (REF) Marques Johnson (PLA) Norm Sloan (COA) Marcus Camby (PLA) George Karl (COA) Ben Wallace (PLA) Michael Cooper (PLA)* Gene Keady (COA) Chris Webber (PLA) Jack Curran (COA) Ken Kern (COA) Willie West (COA) Mark Eaton (PLA) Shawn Marion (PLA) Buck Williams (PLA) Cliff Ellis (COA) Rollie Massimino (COA) Jay Wright (COA) Dale Ellis (PLA) Bob McKillop (COA) Paul Westhead (COA)* Hugh Evans (REF) Danny Miles (COA) Michael Finley (PLA) Steve Moore (COA) Women’s Committee Nominations Leta Andrews (COA) Becky Hammon (PLA) Kim Mulkey (PLA) Jennifer Azzi (PLA) Lauren Jackson (PLA)* Marianne Stanley (COA) Swin Cash (PLA) Suzie McConnell (PLA) Valerie Still (PLA) Yolanda Griffith (PLA)* Debbie Miller-Palmore (PLA) Marian Washington (COA) DIRECT-ELECT CATEGORY: Contributor Committee Nominations Val Ackerman* Simon Gourdine Jerry McHale Marv -

Hannes Kolehmainen in the United States, 1912– 1921 By: Adam Berg, Mark Dyreson Berg, A

The Flying Finn's American Sojourn: Hannes Kolehmainen in the United States, 1912– 1921 By: Adam Berg, Mark Dyreson Berg, A. & Dyreson, M. (2012). The Flying Finn’s American Sojourn: Hannes Kolehmainen in the United States, 1912-1921. International Journal of the History of Sport, 29(7), 1035-1059. doi: 10.1080/09523367.2012.679025 This is an Accepted Manuscript of an article published by Taylor & Francis in International Journal of the History of Sport on 15 May 2012, available online: http://www.tandfonline.com/10.1080/09523367.2012.679025 Made available courtesy of Taylor & Francis: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/09523367.2012.679025 ***© Taylor & Francis. Reprinted with permission. No further reproduction is authorized without written permission from Taylor & Francis. This version of the document is not the version of record. Figures and/or pictures may be missing from this format of the document. *** Abstract: Shortly after he won three gold medals and one silver medal in distance running events at the 1912 Stockholm Olympics, Finland's Hannes Kolehmainen immigrated to the United States. He spent nearly a decade living in Brooklyn, plying his trade as a mason and dominating the amateur endurance running circuit in his adopted homeland. He became a naturalised US citizen in 1921 but returned to Finland shortly thereafter. During his American sojourn, the US press depicted him simultaneously as an exotic foreign athlete and as an immigrant shaped by his new environment into a symbol of successful assimilation. Kolehmainen's career raised questions about sport and national identity – both Finnish and American – about the complexities of immigration during the floodtide of European migration to the US, and about native and adopted cultures in shaping the habits of success. -

Strength Magazine

NOVEMBER 1920 Olympic Number Wrestling tl:t Center Can We Build a Reserve of Energy? StarkStrength Records Price , F ifteen C ents Vol . V Copyright 1920 by 11,e Milo B ar B ell Co. No. 5 ·J JitN-7193? WHAT I'S A BAR-BELL? A bar-bell is simply 3 long handled dumb-bell, and is used for developing exercises. It can be made light enough to suit the needs of any beginner, and heavy enough to provide exercise for the strongest men. It ·is intended for home exercis ing, and cart be used in your bedr oomCenter, no matter how small it is. ·To be of any advantage, a bar-bell must be adjustable, in order that you may beJlin exercising with a moderate weight, and gradually increase that weig)lt as your strength increases. Used in connection wit!} kettle bells and dumb-bells, it is the most efficient exercising aj)pacatus ever devised, and prnduces real health and strength in a remarkably short time, The bar -bell is used by men in every walk of life as a means of keeping in good health, and it has developed all the pro fessio11al Streng mc:i of the country. A REAL STRENGTH BUILDER Why is it that the man who ei<ercises with bar-bells can perform feats of strength far beyond the combined power of two or three ordinary men? Not alone because .)us arms are twice as strong, but because his back, hips and legs are four to five times as strong as those oi the average man who ·uses a system of light exercise .