Defining and Defending the Natural, Native and Legal in the Galápagos Islands of Ecuador

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Author Index

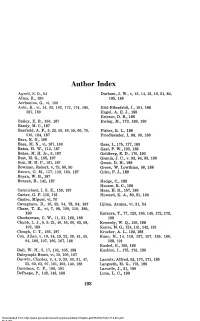

Author Index Agrell, S. 0., 54 Durham, J. W., v, 13, 14, 15, 16, 51, 84, Allen, R., 190 105, 188 Arrhenius, G., vi, 169 Aoki, K, vi, 14, 52, 162, 172, 174, 185, Eibl-Eibesfeldt, I., 101, 188 187, 189 Engel, A. E. J., 188 Ericson, D. B., 188 Bailey, E. B., 166, 187 Ewing, M., 170, 188, 189 Bandy, M. C., 187 Banfield, A. F., 5, 22, 55, 56, 59, 60, 70, Fisher, R. L., 188 110, 124, 187 Friedlaender, I, 98, 99, 188 Barr, K. G., 190 Bass, M. N., vi, 167, 169 Gass, I., 175, 177, 189 Bates, H. W., 113, 187 Gast, P. W., 133, 188 Behre, M. H. Jr., 5, 187 Goldberg, E. D., 170, 190 Best, M. G„ 165, 187 Granja, J. C., v, 83, 84, 85, 188 Bott, M. H. P., 181, 187 Green, D. H., 188 Bowman, Robert, v, 79, 80, 90 Green, W. Lowthian, 98, 188 Brown, G. M., 157, 159, 160, 187 Grim, P. J., 189 Bryan, W. B., 187 Bunsen, R., 141, 187 Hedge, C., 188 Heezen, B. C., 188 Carmichael, I. S. E., 159, 187 Hess, H. H„ 157, 188 Carter, G. F. 115, 191 Howard, K. A., 80, 81,190 Castro, Miguel, vi, 76 Cavagnaro, D., 16, 33, 34, 78, 94, 187 Iljima, Azuma, vi, 31, 54 Chase, T. E., vi, 7, 98, 109, 110, 189, 190 Katsura, T., 77, 125, 136, 145, 172, 173, Chesterman, C. W., 11, 31, 168, 188 189 Chubb, L. J., 5, 9, 21, 46, 55, 60, 63, 98, Kennedy, W. -

Non-Native Small Terrestrial Vertebrates in the Galapagos 2 3 Diego F

1 Non-Native Small Terrestrial Vertebrates in the Galapagos 2 3 Diego F. Cisneros-Heredia 4 5 Universidad San Francisco de Quito USFQ, Colegio de Ciencias Biológicas y Ambientales, Laboratorio de Zoología 6 Terrestre & Museo de Zoología, Quito 170901, Ecuador 7 8 King’s College London, Department of Geography, London, UK 9 10 Email address: [email protected] 11 12 13 14 Introduction 15 Movement of propagules of a species from its current range to a new area—i.e., extra-range 16 dispersal—is a natural process that has been fundamental to the development of biogeographic 17 patterns throughout Earth’s history (Wilson et al. 2009). Individuals moving to new areas usually 18 confront a different set of biotic and abiotic variables, and most dispersed individuals do not 19 survive. However, if they are capable of surviving and adapting to the new conditions, they may 20 establish self-sufficient populations, colonise the new areas, and even spread into nearby 21 locations (Mack et al. 2000). In doing so, they will produce ecological transformations in the 22 new areas, which may lead to changes in other species’ populations and communities, speciation 23 and the formation of new ecosystems (Wilson et al. 2009). 24 25 Human extra-range dispersals since the Pleistocene have produced important distribution 26 changes across species of all taxonomic groups. Along our prehistory and history, we have aided 27 other species’ extra-range dispersals either by deliberate translocations or by ecological 28 facilitation due to habitat changes or modification of ecological relationships (Boivin et al. 29 2016). -

Distribution of Fire Ants Solenopsis Geminata and Wasmannia Auropunctata (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) in the Galapagos Islands

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Aquatic Commons December 2008 Research Articles 11 DISTRIBUTION OF FIRE ANTS SOLENOPSIS GEMINATA AND WASMANNIA AUROPUNCTATA (HYMENOPTERA: FORMICIDAE) IN THE GALAPAGOS ISLANDS By: Henri W. Herrera & Charlotte E. Causton Charles Darwin Research Station, Galapagos, Ecuador. <[email protected]> SUMMARY The Little Fire Ant Wasmannia auropunctata (Roger) and the Tropical Fire Ant Solenopsis geminata (Fabricius) are consid- ered two of the most serious threats to the terrestrial fauna of Galapagos, yet little is known about their distribution in the archipelago. Specimens at the Charles Darwin Research Station and literature were reviewed and distribution maps compiled for both species. W. auropunctata is currently recorded on nine islands and six islets and S. geminata is recorded on seven islands and six islets. New locations were registered, including the first record of W. auropunctata on Española and North Seymour islands, and of S. geminata on Fernandina Island. We recommend further survey, especially in sensitive areas, in order to plan management of these species. RESUMEN La Pequeña Hormiga de Fuego Wasmannia auropunctata (Roger) y la Hormiga Tropical de Fuego Solenopsis geminata (Fabricius) son especies introducidas consideradas de mayor amenaza a la fauna terrestre de Galápagos, sin embargo poco se conoce sobre su distribución en el archipiélago. A través de consultas bibliográficas y revisiones a los especimenes de la Estación Científica Charles Darwin, se determinó su actual distribución. W. auropunctata esta registrada en nueve islas y seis islotes y S. geminata se encuentra en siete islas y seis islotes. -

Management of Introduced Animals in Galapagos

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Aquatic Commons 46 Galapagos Commentary Galapagos Research 65 MANAGEMENT OF INTRODUCED ANIMALS IN GALAPAGOS By: Victor Carrión, Christian Sevilla & Washington Tapia Galápagos National Park, Puerto Ayora, Galapagos, Ecuador. <[email protected]> SUMMARY We review programmes to control or eradicate introduced vertebrates and invertebrates in Galapagos. RESUMEN El manejo de los animales introducidos en Galápagos. Revisamos los programas de control y erradicación de vertebrados e invertebrados en Galápagos. INTRODUCTION trained dogs; a monitoring phase using radio tagged “Judas goats” that associate with remaining feral animals, The arrival of humans in the Galapagos Islands, since after the goat population has been significantly reduced their discovery in 1535, brought a series of negative by aerial and land hunting. Goat eradication projects on impacts and, in some cases, irreversible damage, such as Isabela and Santiago islands reached the monitoring stage the extinction of endemic plants and rodents on several in 2006. At the end of 2006, a goat (and donkey) eradication islands. A major cause of these impacts was the deliberate program was begun on Floreana, and was thought or unintentional introduction of non-native organisms. successful by 2008. Monitoring will continue in order to There have been substantial efforts to eradicate introduced ensure successful eradication. species on the islands over the last 20 years and, in other cases when it has not been possible to eradicate a species, Eradication of feral Pig control activities have at least reversed negative impacts. Pigs were eradiated from Santiago at the end of 2001, after almost 25 years of work. -

Young Tracks of Hotspots and Current Plate Velocities

Geophys. J. Int. (2002) 150, 321–361 Young tracks of hotspots and current plate velocities Alice E. Gripp1,∗ and Richard G. Gordon2 1Department of Geological Sciences, University of Oregon, Eugene, OR 97401, USA 2Department of Earth Science MS-126, Rice University, Houston, TX 77005, USA. E-mail: [email protected] Accepted 2001 October 5. Received 2001 October 5; in original form 2000 December 20 SUMMARY Plate motions relative to the hotspots over the past 4 to 7 Myr are investigated with a goal of determining the shortest time interval over which reliable volcanic propagation rates and segment trends can be estimated. The rate and trend uncertainties are objectively determined from the dispersion of volcano age and of volcano location and are used to test the mutual consistency of the trends and rates. Ten hotspot data sets are constructed from overlapping time intervals with various durations and starting times. Our preferred hotspot data set, HS3, consists of two volcanic propagation rates and eleven segment trends from four plates. It averages plate motion over the past ≈5.8 Myr, which is almost twice the length of time (3.2 Myr) over which the NUVEL-1A global set of relative plate angular velocities is estimated. HS3-NUVEL1A, our preferred set of angular velocities of 15 plates relative to the hotspots, was constructed from the HS3 data set while constraining the relative plate angular velocities to consistency with NUVEL-1A. No hotspots are in significant relative motion, but the 95 per cent confidence limit on motion is typically ±20 to ±40 km Myr−1 and ranges up to ±145 km Myr−1. -

Genovesa Submarine Ridge: a Manifestation of Plume-Ridge Interaction in the Northern Gala´Pagos Islands

Article Geochemistry 3 Volume 4, Number 9 Geophysics 27 September 2003 8511, doi:10.1029/2003GC000531 GeosystemsG G ISSN: 1525-2027 AN ELECTRONIC JOURNAL OF THE EARTH SCIENCES Published by AGU and the Geochemical Society Genovesa Submarine Ridge: A manifestation of plume-ridge interaction in the northern Gala´pagos Islands Karen S. Harpp Department of Geology, Colgate University, Hamilton, New York 13346, USA ([email protected]) Daniel J. Fornari Geology and Geophysics Department, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution, Woods Hole, Massachusetts 02543, USA Dennis J. Geist Department of Geological Sciences, University of Idaho, Moscow, Idaho 83844, USA Mark D. Kurz Marine Chemistry and Geochemistry Department, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution, Woods Hole, Massachusetts 02543, USA [1] Despite its circular coastline and calderas, Genovesa Island, located between the central Galapagos Platform and the Galapagos Spreading Center, is crosscut by both eruptive and noneruptive fissures trending NE-SW. The 075° bearing of the fissures parallels that of Genovesa Ridge, a 55 km long volcanic rift zone that is the most prominent submarine rift in the Galapagos and constitutes the majority of the volume of the Genovesa magmatic complex. Genovesa Ridge was the focus of detailed multibeam and side-scan sonar surveys during the Revelle/Drift04 cruise in 2001. The ridge consists of three left stepping en echelon segments; the abundances of lava flows, volcanic terraces, and eruptive cones are all consistent with constructive volcanic processes. The nonlinear arrangement of eruptive vents and the ridge’s en echelon structure indicate that it did not form over a single dike. Major and trace element compositions of Genovesa Ridge glasses are modeled by fractional crystallization along the same liquid line of descent as the island lavas, but some of the glasses exhibit higher Mg # than material sampled from the island. -

M/S SAMBA ITINERARY 2015 Pristine and Born of Fire (NW Islands)

M/S SAMBA ITINERARY 2015 Pristine and Born of Fire (NW islands) Day 1 – AM: Arrive to Baltra airport Day 1 – PM: Las Bachas - Santa Cruz Island Day 2 – AM: Darwin Bay - Genovesa Island Day 2 – PM: Price Philip’s Steps (El Barranco) - Genovesa Island Day 3 – AM: Punta Mejía - Marchena Island Day 3 – PM: Black beach - Marchena Island Day 4 – AM: Punta Albemarle - Isabela Island Day 4 – PM: Punta Vicente Roca - Isabela Island Day 5 – AM: Punta Espinoza - Fernandina Island Day 5 – PM: Urbina Bay - Isabela Island Day 6 – AM: Elizabeth Bay - Isabela Island Day 6 – PM: Punta Moreno - Isabela Island Day 7 – AM: Asilo de La Paz and Cerro Alleri - Floreana Island Day 7 – PM: La Lobería - Floreana Island Day 8 – AM: Highlands - Santa Cruz Island Day 8 – PM: Baltra - Flight back to Quito or Guayaquil PRISTINE AND BORN OF FIRE: NORTH AND WEST TUESDAY AM: BALTRA AIRPORT PM: LAS BACHAS, Santa Cruz Island On arrival at Baltra Airport all visitors pay their entrance fee to the Galapagos National Park and get their hand luggage checked by the Quarantine system. You will then be met by the Samba’s naturalist guide, who will assist you with your luggage collection and accompany on a short bus ride to the harbor to board Samba. After a light lunch the Samba will navigate for 25 minutes to Las Bachas. This are organic white sand beaches located on the northern shore of Santa Cruz Island and they are the most important nesting site for the green Pacific sea turtles of the Galapagos. -

Galapagos Cruise Itinerary

CONTENTS WELCOME 5 CRUISE ITINERARY 6 8 day cruise 7 San Cristóbal Island 8 Española Island 9 Floreana Island 10 Santa Cruz Island 11 South Plaza Island 12 North Seymour Island 13 Bartholomew Island 14 Isabela Island 15 Fernandina Island 16 Santiago Island 17 Rábida Island 18 ISLAND VISITS 19 Visitor sites 19 Briefings 19 What to take on island excursions 19 Galapagos National Park rules 20 Wetsuit / snorkeling equipment 20 HEALTH & SAFETY 21 Safety 21 Snorkeling & swimming 21 Night time assistance 21 Landings 22 Keys 22 Crew areas 22 Smoking 22 DINING & REFRESHMENTS 23 Meals 23 Bar 23 Ice 23 Water 23 CABINS 24 Air-conditioning 24 Electrical current 24 Housekeeping 24 Beach Towels 24 Shower 24 Caring for the environment 24 Wake-up calls 24 FACILITIES & SERVICES ON BOARD 25 Lounge 25 Bulletin board 25 Telephone 25 Guest Book 25 Shop 25 Payments on board 25 Taxes & service charge 25 Cruise survey 26 Tipping / gratuities 26 Check out & airport transfer 26 ABOUT NINA 27 Deck plans 27 Catamaran specifications 28 Your crew 29 3 Motor Catamaran Nina “It is not the strongest of the species that survives, nor the most intelligent, but the one most responsive to change.” "I have called this principle, by which each slight variation, if useful, is preserved, by the term Natural Selection." “Man tends to increase at a greater rate than his means of subsistence.” “We must, however, acknowledge as it seems to me, that a man with all his noble qualities...still bears in his bodily frame the indelible stamp of his lowly origin.” Charles Darwin Naturalist (1809 - 1882) Motor Catamaran Nina WELCOME ABOARD Dear Guest, Welcome to Galapagos and welcome aboard the Motor Catamaran Nina. -

Island, but It Is Cut Through by Two Narrow Channels, to Leave South Sey- Mour and North Seymour Islands, Extending for Another

NO. 2 FRASER: SCIENTIFIC WORK, VELERO III, EASTERN PACIFIC 225 island, but it is cut through by two narrow channels, to leave South Sey mour and North Seymour islands, extending for another 5% miles north ward. The islands are both low and flat, with much of the surface easily traveled, but there are areas of broken lava rock and low boulders that make it rough. The vegetation is sparse, cactus being most conspicuous, made more sparse by the activities of the numerous goats that roam the islands, or, at least, South Seymour. South Seymour is the home of a large species of land iguana, of a reddish brown color that blends very well with the color of the lava rock where it lives. There are strong tide rips and crosscurrents around and north of the islands. Most of the shore is rocky, but on the west shore of South Sey mour there is a sand beach, probably the largest and finest in the archi pelago, with the most conspicuous faunal feature, the large burrowing hermit crab, which leaves trails everywhere in the sand when the tide is out. On the shores of a small bay (which has been named Velero Bay) near the north end of the west coast of South Seymour, there is an in teresting fossil-bearing stratum exposed. Two rocky islets, Daphne Major and Daphne Minor, lie offshore to the westward, a short distance from South Seymour. They are precipi tous and conspicuous. It is only with difficulty that a landing can be made on either of them. -

INFO GALAPAGOS CENTRAL ISLANDS Daphne Is a Very Small

INFO GALAPAGOS CENTRAL ISLANDS Daphne is a very small island that still maintains its perfect tuff cone and crater shape. It is very fragile due to its type of substrate; therefore very few visitors have a permit to disembark. It is mainly a scientific use zone. Inside the crater there is the biggest Blue footed bobby colony. North Seymour is near Baltra and despite the fact that it is close to the airport it has quite an abundance of sea birds nesting (blue footed boobies, magnificent frigate birds and swallow-tailed gulls) as well as marine iguanas, sea lions and land birds. Mosquera Islet A small, flat, sandy island almost devoid of vegetation. It is located between North Seymour and Baltra Island, and is one of the best places to observe sea lions behavior. Being a sandy and flat island it is a favorite place for these animals. It is also a good area to observe herons, lava gulls and costal birds. South Plaza is a very small island, which has the biggest sea lion colony in the Archipelago and a very healthy population of land iguanas. There are also amazing cliffs and landscape where one can see a variety of sea birds in flight. Santa Fe has one of the most beautiful coves of all the visitor sites in the Galapagos. It has a turquoise lagoon protected by a peninsula that extends from the shore. The ascending trail leads to the peak of a precipice where the Santa Fe species of land iguana can be seen. Back at the landing beach, there is another trail in the opposite direction that runs alongside the coast and then crosses a very picturesque forest of Prickly Cactus. -

Phyllodactylus and Three Subspecies Within the Galápagos Leaf- (Phyllodactylus) from Isabela Island, Toed Gecko (P

Two new species of leaf-toed geckos recognized six species of Phyllodactylus and three subspecies within the Galápagos Leaf- (Phyllodactylus) from Isabela Island, toed Gecko (P. galapagensis). In 1973, Bene- Galápagos Archipelago, Ecuador detto Lanza published a detailed study of the differences in measurements and arrangement http://zoobank.org/3C330FDA-82FE-47CA- of scales among 14 populations of geckos in 8232-DEC69823FC80 Galápagos, and described three new subspe- cies.2 Recently, in 2014, Omar Torres-Carvajal Authors. Alejandro Arteaga,a Lucas Bustaman- and collaborators were the first to study the te,a Jose Vieira,a,b Washington Tapia,c Jorge evolutionary relationships among the islands’ Carrión,d and Juan M Guayasamin.b,e,f leaf-toed geckos using DNA sequences.3 These authors revealed possible colonization a b Tropical Herping (TH), Quito, Ecuador. Uni- and diversification scenarios as well as recog- versidad San Francisco de Quito (USFQ), nized ten species of endemic Phyllodactylus in Colegio de Ciencias Biológicas y Ambientales the archipelago. Of these, two were elevated (COCIBA), Instituto Biósfera, Laboratorio de from subspecies status and two were left as Biología Evolutiva, campus Cumbayá, Quito, undescribed species. Ecuador. cGalapagos Conservancy, Fairfax, United States of America. dDirección del Parque To this day, the two undescribed gecko spe- Nacional Galápagos, Puerto Ayora, Ecuador. cies, and possibly many more, remain without eGalapagos Science Center, Universidad San Francisco de Quito & University of North Caroli- formal scientific names. As a result, these en- na at Chapel Hill, Puerto Baquerizo Moreno, Isla demic Galápagos geckos have not received San Cristóbal, Galápagos, Ecuador. fCentro de formal conservation status assessment and, Investigación de la Biodiversidad y Cambio thus, have not been the focus of targeted Climático, Ingeniería en Biodiversidad y Recur- conservation actions despite facing several sos Genéticos, Universidad Tecnológica Indo- threats of extinction such as displacement by américa, Quito, Pichincha, Ecuador. -

A Legendary Journey Awaits 2019/20 All-Inclusive Galapagos Vacations for Modern Explorers

2016 20162016 201620162016 201620162016 201620162016 201620152016 201520162016 202016152015 201520152016 201520152015 2015 2015 2015 “GOLD “GOLD“GOLD “GOLD“GOLD“GOLD “GOLD“GOLD“GOLD “GOLD“SILVER“GOLD “SILVER“GOLD“GOLD “GOLD“GOLD“SILVER “GOLD“GOLD“GOLD “GOLD“GOLD“GOLD “GOLD “GOLD “GOLD AWARD FOR AWAAWARD FORDR FOR AWAAWARD FORDAWAR FORDR FOR AWAAWARD FORDAWAR FORDR FOR AWAAWRDARD FOAWAR FORDR FOR AWAWAARD FORDAWAR FORDR FOR AWAAWARD FORDAWR FOARDR FOR AWAAWARD RDFOAWA RFORDR FOR AWAAWARD FORDAWAR FORDR FOR AWA“ARDW ARDAWAFOR OFRD FOR “AWARDAWA OF RD FOR “AWARD OF ENTERTAINMENT” ENTERENTERTAINMENT”TAINMENT” ENTERENTETAINMENT”RTENTERAINMENT”TAINMENT” ENTEENTERRTAINMENT”ENTERTAINMENT”TAINMENT” ENTERSUITETAINMENT”ENTE DESIGN”RTAINMENT” SUITESUITE DESIGN”ENTER DESIGN”TAINMENT” SUITERE DESIGN”STASUITEURANT DESIGN” RESTREASTURANTSUITEAURANT DESIGN” RESTREAURANTSTAREURANTSTAURANT RESTEXAURANTCELLENCERESTAURANT” EXCELLENCEREST”AURANT EXCELLENCE” CELEBRITY2016. CRUISES’ 17 2016.17 2016.17 PREMIUM SHIP CATEGORY PREMIU PREMIUM SHIPM CA SHIPTEGO CARYTEGORY PREMIU PREMIUM SHIPM PREMIU CA SHIPTE GOCAMRYTE SHIPGO CARYTEGORY PREMIU PREMIUM SHIPM PREMIU CA SHIPTEGO CAMRYTE SHIPGO CARYTEGORY PREMIU PREMIUMM SHIP PREMIU CA SHIPTEGO CAMRY TEGOSHIP CARYTEGORY PREMIUM PREMIU SHIPM PREMIU CA SHIPTEGO CAMTERY SHIPGO RYCATEGORY PREMIUM SHIP PREMIUMCATEGORY SHIP CATEGORY DESIGN” PREMIUM SHIP CATEGORY CELEBRITY CRUISES’ CELEBRITY CRUISES’ DESIGN” DESIGN” DESIGN”DESIGN”DESIGN” DESIGN”ALL 10 MAIN RESDESIGN”TAURANTS ALL 10 MAIN RESTAURANTDESIGN”S ALL 10 MAIN RESTAURANTS