Phyllodactylus and Three Subspecies Within the Galápagos Leaf- (Phyllodactylus) from Isabela Island, Toed Gecko (P

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

„Fernandina“ – Itinerary

Beluga: „Fernandina“ – Itinerary This itinerary focuses on the Central and Western Islands, including visits to Western Isabela and Ferndina Island, two of the highlights of the Galapagos Islands. Day 1 (Friday): Arrive at Baltra Airport / Santa Cruz Island Santa Cruz Island • Highlands of Santa Cruz: Galapagos giant tortoises can be seen in the wild in the highlands of Santa Cruz • Charles Darwin Station: Visit the Charles Darwin Station is a research facility and National Park Information center. The Charles Darwin Station has a giant tortoise and land iguana breeding program and interpretation center. Day 2 (Saturday): Floreana Island Floreana Island: Floreana is best known for its colorful history of buccaneers, whalers, convicts, and early colonists. • Punta Cormorant: Punta Cormorant has two contrasting beaches and a large inland lagoon where pink flamingoes can be seen. • Devil’s Crown: This is a snorkeling site located just off Punta Cormorant. The site is a completely submerged volcano that has eroded to create the appearance of a jagged crown. • Post Office Bay: This is one of the few sites visited for its human history. Visit the wooden mail barrel where letters are dropped off and picked up and remains of the Norwegian fishing village. Day 3 (Sunday): Isabela Island Isabela Island (Albemarle): Isabela is the largest of the Galapagos Islands formed by five active volcanoes fused together. Wolf Volcano is the highest point in the entire Galapagos at 1707m. • Sierra Negra : Volcan Sierra Negra has a caldera with a diameter of 10km. View recent lava flows, moist highland vegetation, and parasitic cones. • Puerto Villamil: Puerto Villamil is a charming small town on a white sand beach. -

Distribution and Current Status of Rodents in the Galapagos

April 1994 NOTICIAS DE GALÁPAGOS 2I DISTRIBUTION AND CURRENT STATUS OF RODENTS IN THE GALÁPAGOS By: Gillian Key and Edgar Muñoz Heredia. INTRODUCTION (GPNS) and the Charles Darwin Resea¡ch Station (CDRS) in their continuing efforts to protecr the The uniqueness and scientific importance of the unique wildlife of the islands. Galápagos Islands has longbeenrecognized, although the c¡eation of the National Park in 1959 came after ENDEMIC RODENTS several centuries of sporadic use and colonization by man. Undoubtedly, the lack of water in the islands Seven species of endemicricerats a¡eknown from has been thei¡ savior by limiting the extent and dura- the Archipelago, of which the seventh was only rel- tion of many early attempts to colonize. Even so the atively recently discove¡ed from owl pellets on impact of man has been severe in the Archipelago, Fernandina island (Ilutterer & Hirsch 1979), Brosset and the biggest problems for conservation today are ( 1 963 ) and Niethammer ( 1 9 64) have summarized the the introduced species of plants and animals. These available information on the six species known at introduced species are frequently pests to the human that time, including last sightings and probable dates inhabitants as well as to the native flora and fauna, to ofextinction. Galápagosricerats belongto twoclosely the former by damaging crops and goods, and to the related generaof oryzomys rodents and were distrib- latter by competition, predation and transmission of uted among the six islands (Table 1). disease. Patton and Hafner (1983) concluded that rats of The feral mammals in particular constitute a ma- the genus Nesoryzomys arrived in the Archipelago jorproblem, principally due to their size and numbers. -

Introduction Itinerary

GALAPAGOS ISLANDS - ALYA | 6 DAY WESTERN ISLANDS TRIP CODE ECGSA6 DEPARTURE Select Mondays DURATION 6 Days LOCATIONS Galapagos Islands: Santa Cruz, Isabela, Fernandina and Santiago Islands INTRODUCTION GREAT CHIMU SALE EXCLUSIVE: Book and Save up to 33%* off select Departures Explore the Western islands of the Galapagos on this 6 Day Cruise. On board the luxury Alya catamaran you will find a unique blend of high service and comfortable modernity that makes cruising through the Galapagos an unbeatable experience. Within 6 Days you will explore 4 unique islands and smaller islets each extremely different from the last. On the shores of Bachas beach you will find the remnants of WWII US ships, in the highlands of Santa Cruz you may encounter roaming giant tortoises, at Urbina Bay you will witness large colonies of marine iguanas. Each experience in the Galapagos is entirely unique. The Alya Experience The Alya is designed to get the most out of your experience. Launched in 2017, this superior first-class motor catamaran offers comfort and luxury. This is the wonderful vessel to cruise the Galapagos. The ship offers 9 comfortable cabins, all tastefully decorated and featuring private facilities. The catamaran sails with a crew of 8 plus a bilingual, certified naturalist guide ensuring you get the most out of your time onboard the Alya and in the Galapagos. You have the opportunity to explore the Galapagos archipelago with activities such as hiking, snorkelling and kayaking. The cruise can provide you with a comfortable retreat after adventure-packed days of exploration. While sailing the pristine waters you can relax onboard and enjoy the panoramic views from the comfort of the ship. -

Gekkonidae: Hemidactylus Frenatus)

A peer-reviewed open-access journal NeoBiota 27: 69–79On (2015) the origin of South American populations of the common house gecko 69 doi: 10.3897/neobiota.27.5437 RESEARCH ARTICLE NeoBiota http://neobiota.pensoft.net Advancing research on alien species and biological invasions On the origin of South American populations of the common house gecko (Gekkonidae: Hemidactylus frenatus) Omar Torres-Carvajal1 1 Museo de Zoología, Escuela de Ciencias Biológicas, Pontificia Universidad Católica del Ecuador, Avenida 12 de Octubre 1076 y Roca, Apartado 17-01-2184, Quito, Ecuador Corresponding author: Omar Torres-Carvajal ([email protected]) Academic editor: Sven Bacher | Received 11 June 2015 | Accepted 27 August 2015 | Published 15 September 2015 Citation: Torres-Carvajal O (2015) On the origin of South American populations of the common house gecko (Gekkonidae: Hemidactylus frenatus). NeoBiota 27: 69–79. doi: 10.3897/neobiota.27.5437 Abstract Hemidactylus frenatus is an Asian gecko species that has invaded many tropical regions to become one of the most widespread lizards worldwide. This species has dispersed across the Pacific Ocean to reach Ha- waii and subsequently Mexico and other Central American countries. More recently, it has been reported from northwestern South America. Using 12S and cytb mitochondrial DNA sequences I found that South American and Galápagos haplotypes are identical to those from Hawaii and Papua New Guinea, suggest- ing a common Melanesian origin for both Hawaii and South America. Literature records suggest that H. frenatus arrived in Colombia around the mid-‘90s, dispersed south into Ecuador in less than five years, and arrived in the Galápagos about one decade later. -

Notes on Phyllodactylus Palmeus (Squamata; Gekkonidae); a Case Of

Captive & Field Herpetology Volume 3 Issue 1 2019 Notes on Phyllodactylus palmeus (Squamata; Gekkonidae); A Case of Diurnal Refuge Co-inhabitancy with Centruroides gracilis (Scorpiones: Buthidae) on Utila Island, Honduras. Tom Brown1 & Cristina Arrivillaga1 1Kanahau Utila Research and Conservation Facility, Isla de Utila, Islas de la Bahía, Honduras Introduction House Gecko (Hemidactylus frenatus) (Wilson and Cruz Diaz, 1993: McCranie et al., 2005). The Honduran Leaf-toed Palm Gecko Over seventeen years following the (Phyllodactylus palmeus) is a medium-sized Hemidactylus invasion of Utila (Kohler, 2001), (maximum male SVL = 82 mm, maximum our current observations spanning from 2016 female SVL = 73 mm) species endemic to -2018 support those of McCranie & Hedges Utila, Roatan and the Cayos Cochinos (2013) in that P. palmeus is now primarily Acceptedarchipelago (McCranie and Hedges, 2013); Manuscript restricted to undisturbed forested areas, and islands which constitute part of the Bay Island that H. frenatus is now unequivocally the most group on the Caribbean coast of Honduras. The commonly observed gecko species across species is not currently evaluated by the IUCN Utila. We report that H. frenatus has subjugated Redlist, though Johnson et al (2015) calculated all habitat types on Utila Island, having a an Environmental Vulnerability Score (EVS) of practically all encompassing distribution 16 out of 20 for this species, placing P. occupying urban and agricultural areas, palmeus in the lower portion of the high hardwood, swamp, mangrove and coastal vulnerability category. To date, little forest habitats and even areas of neo-tropical information has been published on the natural savannah (T. Brown pers. observ). On the other historyC&F of P. -

Herrera, H.W., Baert, L., Dekoninck, W., Causton, C.E., Sevilla

Belgian Journal of Entomology 93: 1–60 ISSN: 2295-0214 www.srbe-kbve.be urn:lsid:zoobank.org:pub:2612CE09-F7FF-45CD-B52E-99F04DC2AA56 Belgian Journal of Entomology Distribution and habitat preferences of Galápagos ants (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) Henri W. HERRERA, Léon BAERT, Wouter DEKONINCK, Charlotte E. CAUSTON, Christian R. SEVILLA, Paola POZO & Frederik HENDRICKX Royal Belgian Institute of Natural Sciences, Entomology Department, Vautierstraat 29, B-1000 Brussels, Belgium. E-mail: [email protected] (corresponding author) Published: Brussels, May 5, 2020 HERRERA H.W. et al. Distribution and habitat preferences of Galápagos ants Citation: HERRERA H.W., BAERT L., DEKONINCK W., CAUSTON C.E., SEVILLA C.R., POZO P. & HENDRICKX F., 2020. - Distribution and habitat preferences of Galápagos ants (Hymenoptera: Formicidae). Belgian Journal of Entomology, 93: 1–60. ISSN: 1374-5514 (Print Edition) ISSN: 2295-0214 (Online Edition) The Belgian Journal of Entomology is published by the Royal Belgian Society of Entomology, a non-profit association established on April 9, 1855. Head office: Vautier street 29, B-1000 Brussels. The publications of the Society are partly sponsored by the University Foundation of Belgium. In compliance with Article 8.6 of the ICZN, printed versions of all papers are deposited in the following libraries: - Royal Library of Belgium, Boulevard de l’Empereur 4, B-1000 Brussels. - Library of the Royal Belgian Institute of Natural Sciences, Vautier street 29, B-1000 Brussels. - American Museum of Natural History Library, Central Park West at 79th street, New York, NY 10024-5192, USA. - Central library of the Museum national d’Histoire naturelle, rue Geoffroy SaintHilaire 38, F- 75005 Paris, France. -

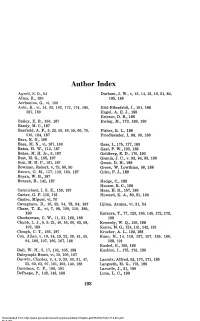

Author Index

Author Index Agrell, S. 0., 54 Durham, J. W., v, 13, 14, 15, 16, 51, 84, Allen, R., 190 105, 188 Arrhenius, G., vi, 169 Aoki, K, vi, 14, 52, 162, 172, 174, 185, Eibl-Eibesfeldt, I., 101, 188 187, 189 Engel, A. E. J., 188 Ericson, D. B., 188 Bailey, E. B., 166, 187 Ewing, M., 170, 188, 189 Bandy, M. C., 187 Banfield, A. F., 5, 22, 55, 56, 59, 60, 70, Fisher, R. L., 188 110, 124, 187 Friedlaender, I, 98, 99, 188 Barr, K. G., 190 Bass, M. N., vi, 167, 169 Gass, I., 175, 177, 189 Bates, H. W., 113, 187 Gast, P. W., 133, 188 Behre, M. H. Jr., 5, 187 Goldberg, E. D., 170, 190 Best, M. G„ 165, 187 Granja, J. C., v, 83, 84, 85, 188 Bott, M. H. P., 181, 187 Green, D. H., 188 Bowman, Robert, v, 79, 80, 90 Green, W. Lowthian, 98, 188 Brown, G. M., 157, 159, 160, 187 Grim, P. J., 189 Bryan, W. B., 187 Bunsen, R., 141, 187 Hedge, C., 188 Heezen, B. C., 188 Carmichael, I. S. E., 159, 187 Hess, H. H„ 157, 188 Carter, G. F. 115, 191 Howard, K. A., 80, 81,190 Castro, Miguel, vi, 76 Cavagnaro, D., 16, 33, 34, 78, 94, 187 Iljima, Azuma, vi, 31, 54 Chase, T. E., vi, 7, 98, 109, 110, 189, 190 Katsura, T., 77, 125, 136, 145, 172, 173, Chesterman, C. W., 11, 31, 168, 188 189 Chubb, L. J., 5, 9, 21, 46, 55, 60, 63, 98, Kennedy, W. -

Non-Native Small Terrestrial Vertebrates in the Galapagos 2 3 Diego F

1 Non-Native Small Terrestrial Vertebrates in the Galapagos 2 3 Diego F. Cisneros-Heredia 4 5 Universidad San Francisco de Quito USFQ, Colegio de Ciencias Biológicas y Ambientales, Laboratorio de Zoología 6 Terrestre & Museo de Zoología, Quito 170901, Ecuador 7 8 King’s College London, Department of Geography, London, UK 9 10 Email address: [email protected] 11 12 13 14 Introduction 15 Movement of propagules of a species from its current range to a new area—i.e., extra-range 16 dispersal—is a natural process that has been fundamental to the development of biogeographic 17 patterns throughout Earth’s history (Wilson et al. 2009). Individuals moving to new areas usually 18 confront a different set of biotic and abiotic variables, and most dispersed individuals do not 19 survive. However, if they are capable of surviving and adapting to the new conditions, they may 20 establish self-sufficient populations, colonise the new areas, and even spread into nearby 21 locations (Mack et al. 2000). In doing so, they will produce ecological transformations in the 22 new areas, which may lead to changes in other species’ populations and communities, speciation 23 and the formation of new ecosystems (Wilson et al. 2009). 24 25 Human extra-range dispersals since the Pleistocene have produced important distribution 26 changes across species of all taxonomic groups. Along our prehistory and history, we have aided 27 other species’ extra-range dispersals either by deliberate translocations or by ecological 28 facilitation due to habitat changes or modification of ecological relationships (Boivin et al. 29 2016). -

Distribution of Fire Ants Solenopsis Geminata and Wasmannia Auropunctata (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) in the Galapagos Islands

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Aquatic Commons December 2008 Research Articles 11 DISTRIBUTION OF FIRE ANTS SOLENOPSIS GEMINATA AND WASMANNIA AUROPUNCTATA (HYMENOPTERA: FORMICIDAE) IN THE GALAPAGOS ISLANDS By: Henri W. Herrera & Charlotte E. Causton Charles Darwin Research Station, Galapagos, Ecuador. <[email protected]> SUMMARY The Little Fire Ant Wasmannia auropunctata (Roger) and the Tropical Fire Ant Solenopsis geminata (Fabricius) are consid- ered two of the most serious threats to the terrestrial fauna of Galapagos, yet little is known about their distribution in the archipelago. Specimens at the Charles Darwin Research Station and literature were reviewed and distribution maps compiled for both species. W. auropunctata is currently recorded on nine islands and six islets and S. geminata is recorded on seven islands and six islets. New locations were registered, including the first record of W. auropunctata on Española and North Seymour islands, and of S. geminata on Fernandina Island. We recommend further survey, especially in sensitive areas, in order to plan management of these species. RESUMEN La Pequeña Hormiga de Fuego Wasmannia auropunctata (Roger) y la Hormiga Tropical de Fuego Solenopsis geminata (Fabricius) son especies introducidas consideradas de mayor amenaza a la fauna terrestre de Galápagos, sin embargo poco se conoce sobre su distribución en el archipiélago. A través de consultas bibliográficas y revisiones a los especimenes de la Estación Científica Charles Darwin, se determinó su actual distribución. W. auropunctata esta registrada en nueve islas y seis islotes y S. geminata se encuentra en siete islas y seis islotes. -

Geographic Range Extension for the Critically Endangered Leaf-Toed

Herpetology Notes, volume 10: 499-505 (2017) (published online on 14 September 2017) Geographic range extension for the critically endangered leaf-toed gecko Phyllodactylus sentosus Dixon and Huey, 1970 in Peru, and notes on its natural history and conservation status Pablo J. Venegas¹,²,*, Renzo Pradel¹, Hatzel Ortiz² and Luis Ríos² Abstract. Here we provide the first record of Phyllodactylus sentosus out of Lima city. This new record extends the known species distribution ca. 318 km (straight line) south-southeastern from the southernmost record at Pachacamac, in the city of Lima. This new record also increases the area of occurrence of the species to 1300 km². All specimens were found near or inside crevices surrounded by dry vegetation on a riverbed. We recorded the air and substrate temperature and the relative humidity during the period of activity of the individuals of P. sentosus, which reached its peak between 21:00 and 22:00 hours. We report the presence of the snake, Bothrops pictus, and other potential predators in the area. Moreover, we present a brief morphological description and describe the variation of the collected specimens. Additionally, we report a new record of P. sentosus in the city of Lima. Finally, we discuss on the basis of our new information, about its ecology and conservation status. Keywords. Costal desert, endemic, Ica, Nasca, Phyllodactylus kofordi, restricted, San Fernando, terminal lamellae. Introduction and Huey, 1970) that inhabits coastal areas with dry soil or sand with scattered rocks and no vegetation (Pérez The leaf-toed gecko Phyllodactylus sentosus is the and Balta, 2016). Within Lima city, this species can only terrestrial reptile from Peru identified as Critically only be found at very small areas primarily located at Endangered according to the Peruvian Wildlife Red List archeological sites (Cossios and Icochea, 2006). -

Cryptic Taxonomic Diversity in Two Broadly Distributed Lizards Of

The Natural History Journal of Chulalongkorn University 1(1): 1-7, August 2001 ©2001 by Chulalongkorn University Cryptic Taxonomic Diversity in Two Broadly Distributed Lizards of Thailand (Mabuya macularia and Dixonius siamensis) as Revealed by Chromosomal Investigations (Reptilia: Lacertilia) HIDETOSHI OTA1*, TSUTOMU HIKIDA2, JARUJIN NABHITABHATA3 AND SOMSAK PANHA4 1 Tropical Biosphere Research Center, University of the Ryukyus, Nishihara, Okinawa 903-0213, JAPAN 2 Department of Zoology, Graduate School of Science, Kyoto University, Kitashirakawa, Sakyo, Kyoto 606-8502, JAPAN 3 Reference Collection Division, National Science Museum, Klong Luang, Pathumthani 12120, THAILAND 4 Department of Biology, Faculty of Science, Chulalongkorn University, Bangkok 10330, THAILAND ABSTRACT.−Karyological surveys were made for two common lizards, Mabuya macularia and Dixonius siamensis, in Thailand. Of the M. macularia specimens karyotyped, the one from Mae Yom, northwestern Thailand, had 2n=38 chromosomes in a graded series as previously reported for a specimen from southwestern Thailand. The other specimens, all from eastern Thailand, however, invariably exhibited a 2n=34 karyotype consisting of four large, and 13 distinctly smaller chromosome pairs. Of the D. siamensis specimens, on the other hand, those from eastern Thailand invariably exhibited a 2n=40 karyotype, whereas three males and one female from Mae Yom had 2n=42 chromosomes. Distinct chromosomal variation was also observed within the Mae Yom sample that may reflect a ZW sex chromosome system. These results strongly suggest the presence of more than one biological species within each of those “broadly distributed species”. This further argues the necessity of genetic surveys for many other morphologically defined “common species” in Thailand and its vicinity in order to evaluate taxonomic diversity and endemicity of herpetofauna in this region appropriately. -

Petrogenesis of Alkalic Seamounts on the Galápagos Platform T ⁎ Darin M

Deep-Sea Research Part II 150 (2018) 170–180 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Deep-Sea Research Part II journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/dsr2 Petrogenesis of alkalic seamounts on the Galápagos Platform T ⁎ Darin M. Schwartza, , V. Dorsey Wanlessa, Rebecca Berga, Meghan Jonesb, Daniel J. Fornarib, S. Adam Souleb, Marion L. Lytlea, Steve Careyc a Department of Geosciences, Boise State University, 1910 University Drive, Boise, ID 83725, United States b Geology and Geophysics Department, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution, United States c Graduate School of Oceanography, University of Rhode Island, United States ARTICLE INFO ABSTRACT Keywords: In the hotspot-fed Galápagos Archipelago there are transitions between volcano morphology and composition, Seamounts effective elastic thickness of the crust, and lithospheric thickness in the direction of plate motion from west to Geochemistry east. Through sampling on the island scale it is unclear whether these transitions are gradational or sharp and Monogenetic whether they result in a gradational or a sharp boundary in terms of the composition of erupted lavas. Clusters of Hotspot interisland seamounts are prevalent on the Galápagos Platform, and occur in the transition zone in morphology Galápagos between western and eastern volcanoes providing an opportunity to evaluate sharpness of the compositional Basalt E/V Nautilus boundary resulting from these physical transitions. Two of these seamounts, located east of Isabela Island and southwest of the island of Santiago, were sampled by remotely operated vehicle in 2015 during a telepresence- supported E/V Nautilus cruise, operated by the Ocean Exploration Trust. We compare the chemistries of these seamount lavas with samples erupted subaerially on the islands of Isabela and Santiago, to test whether sea- mounts are formed from melt generation and storage similar to that of the western or eastern volcanoes, or transitional between the two systems.