The Reign of Nebuchadnezzar I in History and Historical Memory

“This is the first book-length study devoted to the reign of Nebuchadnezzar I, a Babylonian king of the late 12th century BC who is best known to students of ancient Mesopotamia for his recovery of the statue of the national god Marduk from its captivity in Elam. Nielsen achieves two feats of scholarship: he presents a lucid account of Nebuchadnezzar I and his times, and then traces his legacy right down to the Seleukid era, based on careful analysis of a wide range of cuneiform sources including literary texts. His investigation of historical and collective memory within the Mesopotamian cultural tradition represents a major contribution to ancient Near Eastern historiography.”

Heather Baker, University of Toronto, Canada

Nebuchadnezzar I (r. 1125–1104 BCE) was one of the more significant and successful kings to rule Babylonia in the intervening period between the demise of the Kassite Dynasty in the twelfth century at the end of the Late Bronze Age and the emergence of a new, independent Babylonian monarchy in the last quarter of the seventh century. His dynamic reign saw Nebuchadnezzar active on both domestic and foreign fronts. He tended to the needs of the traditional cult sanctuaries and their associated priesthoods in the major cities throughout Babylonia and embarked on military campaigns against both Assyria in the north and Elam to the east. Yet later Babylonian tradition celebrated him for one achievement that was little noted in his own royal inscriptions: the return of the statue of Marduk, Babylon’s patron deity, from captivity in Elam.

The Reign of Nebuchadnezzar I in History and Historical Memory reconstructs

the history of Nebuchadnezzar I’s rule and, drawing upon theoretical treatments of historical and collective memory, examines how stories of his reign were intentionally utilized by later generations of Babylonian scholars and priests to create a historical memory that projected their collective identity and reflected Marduk’s rise to the place of primacy within the Babylonian pantheon in the first millennium BCE. It also explores how this historical memory was employed by the urban elite in discourses of power. Nebuchadnezzar I remained a viable symbol, though with diminishing effect, until at least the third century BCE, by which time his memory had almost entirely faded. This study is a valuable resource to students of the Ancient Near East and Nebuchadnezzar, but is also a fascinating exploration of memory creation and exploitation in the ancient world.

John P. Nielsen is Assistant Professor of History at Bradley University, Peoria, IL, USA.

Studies in the History of the Ancient Near East

Series editor: Greg Fisher

Carleton University, Canada Studies in the History of the Ancient Near East provides a global forum for

works addressing the history and culture of the Ancient Near East, spanning a broad period from the foundation of civilisation in the region until the end of the Abbasid period. The series includes research monographs, edited works, collections developed from conferences and workshops, and volumes suitable for the university classroom.

Available titles:

Being a Man

Negotiating Ancient Constructs of Masculinity

Edited by Ilona Zsolnay

“Losing One’s Head” in the Ancient Near East

Interpretation and Meaning of Decapitation

Rita Dolce

The Reign of Nebuchadnezzar I in History and Historical Memory

John P . N ielsen

Discovering Babylon

Rannfrid Thelle

For more information about this series, please visit: https://www.routledge. com/classicalstudies/series/HISTANE

The Reign of Nebuchadnezzar I in History and Historical Memory

John P. Nielsen

First published 2018 by Routledge 2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon OX14 4RN

and by Routledge 711 Third Avenue, New York, NY 10017

Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an informa business

© 2018 John P. Nielsen The right of John P. Nielsen to be identified as author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with sections 77 and 78 of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers.

Trademark notice: Product or corporate names may be trademarks or registered trademarks, and are used only for identification and explanation without intent to infringe.

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

A catalog record has been requested for this book ISBN: 978-1-138-12040-2 (hbk) ISBN: 978-1-315-64826-2 (ebk)

Typeset in Sabon by Apex CoVantage, LLC

For Mom and Dad Dawn and John Mark – Milli and Steve

Contents

List of figures List of map

xxi

List of tables

xii

Foreword – histor y , m emor y , a nd the past Acknowledgments List of abbreviations

xiii xx xxii

PART I

Writing history and recovering memory, sources and methodologies

1

3

- 1

- Toward an understanding of the Babylonian memory

of Nebuchadnezzar I

1.1 Nebuchadnezzar I 3 1.2 Nebuchadnezzar I and historical memory 6 1.3 Babylonian historical consciousness 11 1.4 Nebuchadnezzar I and historical memory: a prospectus 14

- 2

- Nebuchadnezzar I: prior scholarship, historical sources,

and chronology

22

2.1 Prior scholarship 22 2.2 Historical sources 25 2.3 Writing of the royal name 34 2.4 Chronology 37

PART II

Nebuchadnezzar I and his times

47

49

- 3

- The reign of Nebuchadnezzar I

3.1 The origins of the Second Dynasty of Isin 49 viii Contents

3.2 The reign of Nebuchadnezzar I 51 3.3 Conclusions 68

- 4

- Nebuchadnezzar I’s successors

78

4.1 Enlil-n ā din-apli 78 4.2 Marduk-n ā din-a ḫḫē 79 4.3 Marduk-š ā pik-z ē ri 82 4.4 Conclusions 83

PART III

Remembering Nebuchadnezzar I in the first millennium BCE

89

91

- 5

- Esarhaddon and the return of Marduk in 668 BCE

5.1 Introduction 91 5.2 Ashurbanipal’s library and the Nebuchadnezzar I literary tablets 92

5.3 The past repeated: the departure and return of Marduk in the seventh century 94

5.4 Nebuchadnezzar I and the discourse at

Esarhaddon’s court 104

5.5 Conclusions 114

- 6

- Remembering Nebuchadnezzar I from the zenith

of Babylonian power through the Seleucid era

126

6.1 Introduction 126 6.2 Nebuchadnezzar I in the Neo-Babylonian Empire 127 6.3 Nebuchadnezzar I in Achaemenid Babylonia 129 6.4 Nebuchadnezzar I in Hellenistic Babylonia 134 6.5 Conclusions 137

PART IV

The making of memory and the making of meaning

147

149

- 7

- Nebuchadnezzar I in the collective memory

7.1 The early first millennium BCE: crisis and continuity 149 7.2 The making of memory 151 7.3 Nebuchadnezzar I in collective memory 153 7.4 Conclusions 158

Contents ix

89

The elevation of Marduk: Nebuchadnezzar I as cultural formation

163

8.1 The creation of meaning 163 8.2 Syncretic thought 177 8.3 Conclusions 180

Intentional history in the early first millennium BCE

189

9.1 Introduction 189 9.2 Scholarly culture during the Second Dynasty of Isin 191

9.3 Babylonia from the tenth through the eighth centuries BCE 193

9.4 Intentional history 199 9.5 Conclusions 204

Index

213

Figures

3.1 The Šitti-Marduk kudurru 3.2 The Eriya stone tablet

54 63

4.1 Family tree of Ninurta-nādin-šumi’s descendants 7.1 The Sun-god Tablet of Nabû-apla-iddina

79

150

Map

0.1 The Ancient Near East during the reign

- Nebuchadnezzar I

- xxiv

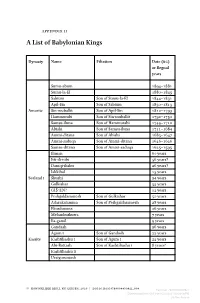

Tables

2.1 Writings of “Nebuchadnezzar I” 3.1 Kings of Babylon in the late second millennium BCE

35 50

Foreword – history, memory, and the past

As a history professor, it is inevitable that one will encounter certain popular quotations pertaining to the field. These usually appear taped to an office door on yellowed, typewritten paper or as a seemingly fresh and profound insight in the introduction to a student’s paper and have attained the status of maxims or even platitudes about the relevance of the field. Two such quotations come to mind:

Those who cannot remember the past are condemned to repeat it.

George Santayana

The second quotation I have seen is from a play by William Faulkner. Though the quotation is not cited here,1 the reader may be familiar with it. The two short sentences succinctly express the enduring presence of the past in our present and question if the past really exists at a different temporal point from our own.

In our present digital age we might even call these aphorisms memes. It is notable, however, that neither one of these quotations comes from a historian nor do they even include the word history. Rather, they reflect the commonly held understanding of the word past as a synonym for history, that is, the sum of all time that has preceded the present. When a TV broadcaster commenting on some live event informs the audience that they are watching history in the making, nothing could be further from the truth (the process of making history is far less glamorous). What viewers are watching is the present, a present that will in an instant become the past.The popular usages of the word past as it appeared earlier, the ones conflated with the word his- tory, only value select pasts because they are relevant to the present. These pasts might be forgotten and as a result repeated, or, more troubling, they may never actually go away. Implicit in these quotations is the existence of a useable past within the context of the present that does not encompass the entirety of chronological time that came before. The creation of this useable past, as will be seen in the chapters to come, is complex. It is a selective and negotiated process both in terms of which pasts are privileged and therefore remembered and preserved, and how those pasts are given meaning through

xiv Foreword – histor y , m emor y , a nd the past

interpretation. Importantly, the past itself cannot be made up. It has or, more accurately, had an objective reality when it was present. Multiple and potentially competing voices play a role in shaping such useable pasts, drawing upon both memory and the physical remains of the past such as artifacts and written materials, but they consistently serve the needs of the present and are maintained in such a way that they seem to reflect broad social consensus and therefore appear to be established as fact. As a result, those who reference these pasts often do so with the conviction that the past is absolute and unchanging, mistakenly equating the meanings that they have given to the past with the events to which these meanings have become attached.

I am reminded of this popular use of the past whenever I drive northbound on the Dan Ryan Expressway in Chicago. Off to the right, framed against the city’s impressive skyline, there is a large mural painted on one of the many warehouses that still stand near the canal. With American flags framing the far ends, the dates Dec. 7, 1941 and Sep. 11, 2001 flank a patriotic declaration,“America will not Forget!”The dates have and require no explanation. It is expected that viewers will know the significance of Pearl Harbor and 9–11 – twice America was attacked and twice Americans banded together to defeat a great evil – and those who do not know can be informed by those who do. That the majority of motorists passing the mural were not alive during World War II and therefore have no personal memory of Pearl Harbor is irrelevant. It has been maintained in the popular historical memory as an event that should not be forgotten, and so could be meaningfully and intentionally linked to the events of 9–11 to justify the war in Afghanistan, the second war in Iraq, and the more nebulous War on Terror. Importantly, this popular memory does not encompass the entirety of America’s past. Feb. 15, 1898 could just as easily have found a place on the mural, but in spite of calls at the time to “Remember the Maine!” the Spanish-American War and the events that preceded it have largely faded from the American historical memory. It is not even remembered as “the forgotten war.” The Korean War claims that distinction.

Clearly, then, there are pasts that matter – the ones that would not even be past in Faulkner’s thinking – and pasts that do not matter – those that we can conveniently forget without any fear of repeating them in spite of Santayana’s warning. Furthermore, the pasts that matter are considered inviolable because they happened. Barring the invention of the time machine, the past cannot be changed, and therefore we assume its meaning cannot be changed. To offer another personal anecdote as an illustration, I once sat next to a gentleman on a flight, who, upon learning that I was a historian, proceeded to tell me how he was a bit of a history buff himself and that he was descended from one of the signatories of South Carolina’s 1860 “Ordinance of Secession.” The Civil War, he assured me, was fought over states’ rights and not over slavery; he liked history, but he did not care much for revisionist historians who offered interpretations of the past that conflicted with the “correct” history he had learned. For him the unchangeable past

Foreword – histor y , m emor y , a nd the past xv

and the interpretation of its significance – the work of the historian – were one and the same.

Throughout time, perspectives close to the one expressed by my flight companion have probably typified the way many societies have regarded their pasts. We are the ones who live in an era that is unique. Modern academic institutions support a population of professional historians who enjoy the luxury of pursuing lines of inquiry into the past that are not determined by popular interests or assumptions but instead by the questions of likeminded specialists. This is especially true for an Assyriologist, a scholar of the Ancient Near Eastern languages written with cuneiform script, in a society in which describing something as “ancient history” relegates it to complete irrelevance. Furthermore, ever since Leopold von Ranke’s 1824 exhortation to historians to describe the past “wie es eigentlich gewesen” (“as it actually was”), historians have given considerable thought not just to history but also to historiography, that is, the methodologies for recovering the past for the purpose of writing history. Because the past is a place that no historian can actually visit, the approaches for critically evaluating and understanding evidence about the past are crucial to the historian. These methods have changed considerably. They have simultaneously shaped and have been shaped by developments in other disciplines in the humanities and social sciences over the course of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries and continue to do so at the outset of the twenty-first. Just as the subjects that academic historians take up can be unfamiliar to a popular audience, so too the precision of language required for historiographical discussions has resulted in the creation of specialized jargon that has rendered much writing of academic history inaccessible to that same audience.

Neither of these developments are necessarily bad things. From a humanistic standpoint, there is an inherent value in exploring unfamiliar histories in order to expand the breadth of human experience, and the recognition that human societies select the pasts that they remember and assign meanings to those pasts gives us greater agency in the writing of history. All pasts are ours, and no past is imposed upon us. At the same time, historical inquiry should also contribute to furthering intellectual projects and answering broader questions. However, achieving these goals with our subject, the Babylonian king Nebuchadnezzar I, brings challenges of accessibility. How do we simultaneously address the specific concerns and interests of an informed, specialist audience of Assyriologists and the broader questions of scholars from other disciplines who share similar theoretical approaches and interests in historical memory, while also making the contents comprehensible to an educated, generalist audience? Out of necessity, we will provide far more background information – not only on the reign of Nebuchadnezzar I, but also on historical events and cultural developments that contextualize his reign and his legacy – than would be required by an Assyriologist reading this work, though what follows will not be a straightforward narrative history. Furthermore, we intend to address those scholars interested in the role

xvi Foreword – histor y , m emor y , a nd the past

of historical memory within society and will be especially mindful of ancient historians who work on non-Mesopotamian topics, particularly those who work on the history of Classical antiquity.

Such an undertaking brings with it both the challenges and advantages of writing on ancient history. It has been my experience that for many people, the task of understanding antiquity is conditioned by their vantage point in time as it is shaped by our rapidly changing modern world. From such a removed perspective it is easy to regard antiquity as static, and there is a tendency to compress all of the ancient past into a singular past without an appreciation of the extensive period of time that we today classify as the ancient past. The passing of the years, however, was just as real then as it is for us today, and those who lived in antiquity had a past that they sought to make sense of in their own present. With this in mind, it is important to appreciate that a scribe at the city of Uruk who wrote the last tablet that we know of mentioning Nebuchadnezzar I during the Seleucid period (c. 244 BCE) was about as far removed in time from the king’s reign (1125–1104 BCE) as we are from William the Conqueror’s victory at Hastings in 1066.

What makes Nebuchadnezzar I such an interesting subject is not just the events of his reign – these were significant, but stand out in part due to his successes during an era when Babylonia underwent prolonged periods of instability and weakness – but also the way they were regarded and remembered by both Babylonians and Assyrians over the millennium that would follow. As will be seen, Nebuchadnezzar’s legacy took on a variety of meanings, and these could be intentionally adapted as instruments for those who wished to further their own political and religious ambitions throughout Babylonia. The processes by which the memory of Nebuchadnezzar I was maintained and revived were probably varied, and exploring them affords us a chance to examine the rich intellectual culture of Babylonian and Assyrian scholars and their interactions with the monarchy. It also presents us with an opportunity to speculate on what knowledge and ideas about the past were preserved in the popular memory among the general population. What pasts were not even past for the people of Babylonia and what were the means – the ancient equivalents of large, publicly displayed murals along the Dan Ryan – of keeping those pasts in the present? How did popular memory of the past inform perceptions of events? How could these perceptions be used and shaped by the actions of both the ruling and scholarly classes, but also how did popular memory limit such manipulations?

We opened with some contemporary examples of the past as it has been memorialized or preserved in our present. The South that Faulkner wrote about in the early twentieth century was less than a century removed from the American Civil War, and for some that past continues to be neither dead nor past. Similarly, the events of 9–11 and the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq that followed remain part of our national discourse, but it is yet to be seen if they will be remembered a century in the future. Nebuchadnezzar I, it is