MLK Marker Brochure Version 4.Indd

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Atlanta Student Movement Project Dr. Lonnie King Class Lecture 2017 Transcribed by Jeanne Law Bohannon

Atlanta Student Movement Project Dr. Lonnie King Class Lecture 2017 Transcribed by Jeanne Law Bohannon KING: I played fullback and ended up being a linebacker. I was a linebacker on the left side. Yeah. Because I didn't want to play on the right side. I played on the left side as a, as a linebacker. So, I played fullback, halfback, and linebacker. Yeah, I was mean, brother. One thing about athletics, at least from my perspective, it's a very good thing for young people to play athletics because you learn teamwork you learn disappointment, highs and lows, all that. All those things are good to get exposed to when you're young because I think it makes you, in my opinion, a better citizen later on. Those guys and those ladies who just bookworm all the time - they are brilliant people, make all As, but they are somewhat not as balanced as young ladies and young men who become more athletically inclined. I was glad to see Title IX passed because I remember my daughter, she and I used to play basketball together when she was young. She was very good, but she couldn't play after she got to high school because that's how it was at that time. Yeah. But anyway, my little son was pretty good. I was just thinking yesterday, I guess it was, because he called me from up in Kentucky. I was thinking about it when he was five years old. I used to take my five-year-old and my ten-year-old to play three-person basketball with the folks in the neighborhood. -

Atlanta's Civil Rights Movement, Middle-Class

“To Secure Improvements in Their Material and Social Conditions”: Atlanta’s Civil Rights Movement, Middle-Class Reformers, and Workplace Protests, 1960-1977 by William Seth LaShier B.A. in History, May 2009, St. Mary’s College of Maryland A Dissertation submitted to The Faculty of The Columbian College of Arts and Sciences of The George Washington University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy January 10, 2020 Dissertation directed by Eric Arnesen James R. Hoffa Teamsters Professor of Modern American Labor History The Columbian College of Arts and Sciences of The George Washington University certifies that William Seth LaShier has passed the Final Examinations for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy as of November 20, 2019. This is the final and approved form of the dissertation. “To Secure Improvements in Their Material and Social Conditions”: Atlanta’s Civil Rights Movement, Middle-Class Reformers, and Workplace Protests, 1960-1977 William Seth LaShier Dissertation Research Committee Eric Arnesen, James R. Hoffa Teamsters Professor of Modern American Labor History, Dissertation Director Erin Chapman, Associate Professor of History and of Women’s Studies, Committee Member Gordon Mantler, Associate Professor of Writing and of History, Committee Member ii Acknowledgements I could not have completed this dissertation without the generous support of teachers, colleagues, archivists, friends, and most importantly family. I want to thank The George Washington University for funding that supported my studies, research, and writing. I gratefully benefited from external research funding from the Southern Labor Archives at Georgia State University and the Stuart A. Rose Manuscript, Archives, and Rare Books Library (MARBL) at Emory University. -

NEH Coversheet

Narrative Section of a Successful Application The attached document contains the grant narrative and selected portions of a previously funded grant application. It is not intended to serve as a model, but to give you a sense of how a successful application may be crafted. Every successful application is different, and each applicant is urged to prepare a proposal that reflects its unique project and aspirations. Prospective applicants should consult the Humanities Initiatives at Historically Black Colleges and Universities application guidelines at http://www.neh.gov/grants/education/humanities-initiatives-historically-black-colleges-and- universities for instructions. Applicants are also strongly encouraged to consult with the NEH Division of Education Programs staff well before a grant deadline. Note: The attachment only contains the grant narrative and selected portions, not the entire funded application. In addition, certain portions may have been redacted to protect the privacy interests of an individual and/or to protect confidential commercial and financial information and/or to protect copyrighted materials. Project Title: Humanities Teaching and the Martin Luther King, Jr. Collection at Morehouse College Institution: Morehouse College Project Director: Vicki Lynn Crawford Grant Program: Humanities Initiatives at Historically Black Colleges and Universities 400 7th Street, SW, Washington, DC 20024 P 202.606.8500 F 202.606.8394 E [email protected] www.neh.gov Infusing the Morehouse College Martin Luther King, Jr. Collection into Humanities Teaching TABLE OF CONTENTS Page Summary 1 Narrative Intellectual Rationale 2-3 Content and Design 3-9 Project Personnel 9 Institutional Context 9 Follow-Up and Dissemination 10 Evaluation 10 Budget 11-14 Budget Narrative 15 Appendix Appendix A—Work Plan/Schedule of Activities 16-18 Appendix B—Workshops —National Center for Civil and Human Rights 19-21 Appendix C—Workshop--Atlanta University Robert Woodruff Library 22 Appendix D—Abbreviated Resume, Public Program Lecturer—Dr. -

Stadiums of Status: Civic Development, Race, and the Business of Sports in Atlanta, Georgia, 1966-2019

i Stadiums of Status: Civic Development, Race, and the Business of Sports in Atlanta, Georgia, 1966-2019 By Joseph Loughran Senior Honors Thesis History University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill May 1, 2020 Approved: ___________________________________ Dr. Matthew Andrews, Thesis Advisor Dr. William Sturkey, Reader i Acknowledgements I could not have completed this thesis without the overwhelming support from my mother and father. Ever since I broached the idea of writing a thesis in spring 2019, they not only supported me, but guided me through the tough times in order to create this project. From bouncing ideas off you to using your encouragement to keep pushing forward, I cannot thank the both of you enough. I would also like to thank my advisor, Dr. Matthew Andrews, for his constant support, guidance, and advice over the last year. Rather than simply giving feedback or instructions on different parts of my thesis, our meetings would turn into conversations, feeding off a mutual love for learning about how sports impact history. While Dr. Andrews was an advisor for this past year, he will be a friend for life. Thank you to Dr. Michelle King as well, as her guidance throughout the year as the teacher for our thesis class was invaluable. Thank you for putting up with our nonsense and shepherding us throughout this process, Dr. King. This project was supported by the Tom and Elizabeth Long Excellence Fund for Honors administered by Honors Carolina, as well as The Michel L. and Matthew L. Boyatt Award for Research in History administered by the Department of History at UNC-Chapel Hill. -

•Umiaccessing the World's Information Since 1938

INFORMATION TO USERS The most advanced technology has been used to photo graph and reproduce this manuscript from the microfilm master. UMI films the original text directly from the copy submitted. Thus, some dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from a computer printer. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyrighted material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are re produced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand corner and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Each oversize page is available as one exposure on a standard 35 mm slide or as a 17" x 23" black and white photographic print for an additional charge. Photographs included in the original manuscript have been reproduced xerographically in this copy. 35 mm slides or 6" x 9" black and white photographic prints are available for any photographs or illustrations appearing in this copy for an additional charge. Contact UMI directly to order. •UMIAccessing the World's Information since 1938 300 North Zeeb Road, Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 USA Order Number 8803795 The Civil Rights Movement Sellers, Cleveland L., Jr., Ed.D. The University of North Carolina at Greensboro, 1987 Copyright ©1987 by Sellers, Cleveland L., Jr. All rights reserved. UMI 300 N. Zeeb Rd. Ann Arbor, MI 48106 THE CIVIL RIGHTS MOVEMENT by Cleveland L. SELLERS Jr. A Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School at The University of North Carolina at Greensboro in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Education Greensboro 1987 Approved by APPROVAL PAGE This dissertation has been approved by the following committee of the Faculty of the Graduate School at The University of North Carolina at Greensboro. -

C I T Y O F a T L a N

C I T Y O F A T L A N T A KEISHA LANCE BOTTOMS DEPARTMENT OF CITY PLANNING TIM KEANE MAYOR 55 Trinity Avenue, S.W. SUITE 3350 – ATLANTA, GEORGIA 30303-0308 Commissioner 404-330-6145 – FAX: 404-658-7491 www.atlantaga.gov KEVIN BACON, AIA, AICP Director, Office of Design MEMORANDUM TO: Atlanta Urban Design Commission FROM: Doug Young, Executive Director ADDRESS: 389 Hopkins St. APPLICATION: CA2-20-255 MEETING DATE: March 24, 2021 ________________________________________________________________________________ FINDINGS OF FACT: Historic Zoning: West End Historic District Other Zoning: R-4A / Beltline. Date of Construction: Vacant Property Location: West block face of Hopkins St., north of Greenwich St., south of the Sells Ave. Contributing (Y/N)?: N/A. Building Type / Architectural form/style: Infill. Project Components Subject to Review by the Commission: New Construction of a SFR. Project Components NOT Subject to Review by the Commission: N/A. Relevant Code Sections: Sec. 16-20 and Sec. 16-20G Deferred Application (Y/N)?: Yes. Deferred 03/10/2021. Updated text in Underlined Italics. Previous Applications/Known Issues: In May of 2020, Staff was alerted to concerns that the house was being built taller than was approved by the Commission and other issues with the as built design not matching the design approved by the Commission. In an investigation of the situation, Staff discovered that the height comparison provided by the Applicant was inaccurate, leading to the Commission approving a height range which was 10’ taller than the tallest historic home on the block face. Other inaccuracies in the construction, including an as built first floor height which exceeded the allowable maximum by 2 feet, were also discovered. -

FINAL Precinct Locations 6 9 2020 05312020.Xlsx

Precinct Locations - June 9, 2020 5.29.2020 Precinct Facility Name Precinct Address Precinct City / Zip 01A Parkside Elementary School 685 Mercer Street SE Atlanta, GA 30312 01B Ormewood Park Presbyterian Church 1071 Delaware Avenue SE Atlanta, GA 30316 01C & 01S & 12F Dobbs Elementary School 2025 Jonesboro Road SE Atlanta, GA 30315 01D & 01E & 01G FanPlex 768 Hank Aaron Drive SE Atlanta, GA 30315 01F FanPlex 768 Hank Aaron Drive SE Atlanta, GA 30315 01H & 05B/C Liberty Baptist Church 395 Chamberlain Street SE Atlanta, GA 30312 01J & 12S Louise Watley Library at Southeast Atlanta 1463 Pryor Road SW Atlanta, GA 30315 01P Bible Way Ministries 894 Constitution Road SE Atlanta, GA 30315 01R Thomasville Recreation Center 1835 Henry Thomas Dr SE Atlanta, GA 30315 01T Benteen Elementary School 200 Casanova Street SE Atlanta, GA 30315 02A & 02L1 Park Tavern 500 10th Street NE Atlanta, GA 30309 02B & 02L2 & 05D Liberty Baptist Church 395 Chamberlain Street SE Atlanta, GA 30312 02C & & 02F1/2 & 05F Central Park Recreation Center 400 Merritts Avenue NE Atlanta, GA 30308 02D & 05J & 06F Butler Street Baptist Church 315 Ralph McGill Blvd NE Atlanta, GA 30312 02E Little 5 Point Community Center 1083 Austin Avenue NE Atlanta, GA 30307 02G Helene Mills Senior Center 515 John Wesley Dobbs Ave NE Atlanta, GA 30312 02J & 02K & 06G Park Tavern 500 10th Street NE Atlanta, GA 30309 02S & 05K Helene Mills Senior Center 515 John Wesley Dobbs Ave NE Atlanta, GA 30312 02W & 03F & 06L1/2 Peachtree Christian Church 1580 Peachtree Street NW Atlanta, GA 30309 03A Allen Temple African Methodist Episcopal Church 1625 Joseph E. -

Civil Rights Trail & Gospel Roots of the King

Civil Rights Trail & Gospel Roots of The King Featuring Atlanta, Montgomery, Selma, Birmingham, Tupelo, and Memphis 9 Days / 8 Nights Day 1 - Tour CNN Center and National Center for Civil & historically black college, then depart for Selma. Depart and walk Human Rights across Pettus Bridge, site of the brutal bloody Sunday beatings of Enjoy lunch on own at CNN Center Food Court, which offers a variety civil rights marchers during the first march for voting rights. It is of dining experiences, from fast casual to full-service, in the heart of named after Edmund Pettus, a Confederate brigadier general, downtown Atlanta. Tour CNN Atlanta Studio, see the science, Democratic U.S. Senator and grand wizard of the Alabama Klu Klux and origin of TV news making at CNN's Headquarters. Visit the Klan. Enjoy dinner included at a local Southern Cuisine chef owned National Center for Civil & Human Rights, a museum dedicated to establishment. The chef takes many traditional dishes, and mixes the achievements of both the civil rights movement in the U.S. and the both international and European styles to bring to you a dining broader worldwide human rights movement. Depart and transfer to experience that takes the meaning of 'fine dining' to a new plateau. your hotel and check in. Enjoy a combination of comfort and savior faire you'll not find anywhere else! Depart and check into hotel. Day 2 - MLK Jr. National Historic Park & Civil Rights Tour Enjoy breakfast at the hotel prior to checking out. Baggage handling Day 4 - Tour Voting Rights Museum & Historical Sites is included. -

Research Addendum

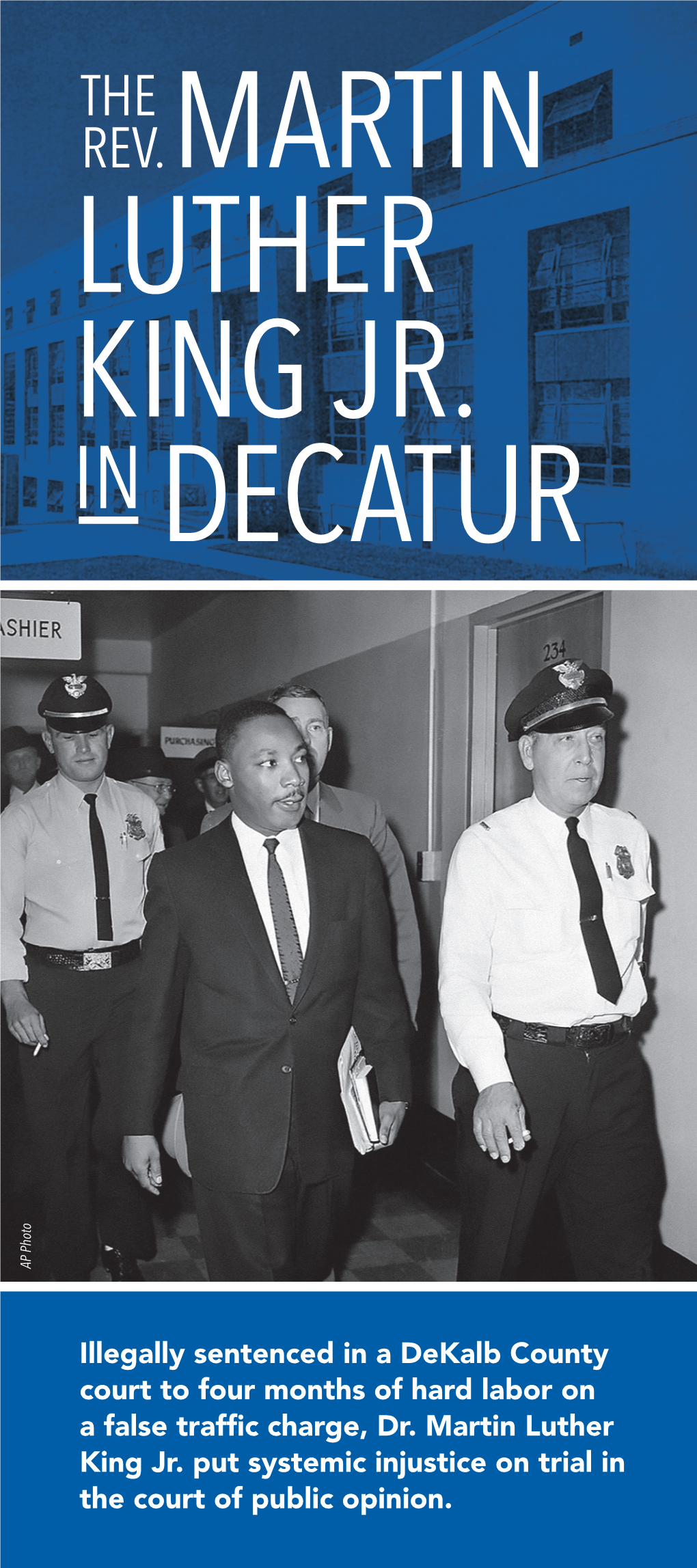

Oct. 2, 2020 The Georgia Historical Society, in approving the marker, raised some important questions about the context, impact and legacy of Martin Luther King Jr.’s treatment in Decatur in 1960. Here is a brief attempt to address them: ● How was King’s experience in Decatur an example of systemic racism in civic institutions (King’s harsh sentence for a minor infraction). Martin Luther King Jr.’s experience in Decatur -- being sent to a chain gang for using his Alabama driving license in Georgia -- exposed systemic American racial injustice. His stature brought national attention to the acts of civil disobedience already committed by hundreds of students in dozens of Southern cities in 1960. Georgia’s segregationist leaders were hoping to smother this movement by showing Black people that the criminal justice system would humiliate even their most prominent representatives. Movement leaders, meanwhile, were determined to put the entire system on trial in the court of public opinion, making King a martyr to mobilize mass resistance and hopefully force the federal government to end legalized racial discrimination once and for all. When Georgia Gov. Ernest Vandiver’s top aide, Peter Zach Geer, declared at King’s sentencing that the chain gang “might make a law-abiding citizen out of him and teach him to respect the law of Georgia,”1 he was referring to a system of legal oppression maintained to ensure white supremacy and effectively re-enslave African-Americans across the South after the Civil War, so that white people could justify benefiting from the labor of Black people at little or no cost. -

216050251.Pdf

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by ETD - Electronic Theses & Dissertations RAISING A NONVIOLENT ARMY: FOUR NASHVILLE BLACK COLLEGES AND THE CENTURY-LONG STRUGGLE FOR CIVIL RIGHTS, 1830s-1930s By Crystal A. deGregory Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Vanderbilt University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in History May 2011 Approved: Professor Richard J. M. Blackett Professor Lewis V. Balwin Professor Gary Gerstle Professor Daniel H. Usner, Jr. Copyright © 2011 by Crystal A. deGregory All Rights Reserved To Dr. L.M. Collins, the embodiment of the HBCU teacher tradition; and Mr. August Johnson, for his ever-present example and encouragement. iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This work would not have been possible without the Vanderbilt University History Department, whose generous support allowed me to write and research this dissertation. I am grateful to the College of Arts and Sciences in particular, for awarding this project Social Science Dissertation Fellowship for the 2007/8 academic year. Similarly, I am also deeply indebted to The Commonwealth of the Bahamas‘ Ministry of Education for awarding me Bahamas Government Graduate Student Scholarships 2008/9 and 2009/10, and grateful to its helpful staff, especially Ann Russell of the Freeport Department. Finally, I would like to thank the Lyford Cay Foundation of Nassau, Bahamas for its financial support via the Lyford Cay Foundation Graduate Student Scholarship during the 2009/10 academic year and Lyford Cay Educational Programmes and Alumni Affiars Director Monique A. Hinsey in particular who was a godsend. -

Atlanta Important Historic Sites Not Open for Visitation

ATLANTA APEX Museum Milton’s Drugstore The Jimmy Carter Presidential Library and Museum Located in the historic Atlanta School Book Depository At the former site of Yates & Milton Drug Store (presently The Jimmy Carter Presidential Library and Museum, Martin Luther King, Jr. National Historical Park building in the heart of Atlanta’s Sweet Auburn Historic the Student Center on the campus of Clark Atlanta administered by the National Archives and Record The experience at the Martin Luther King, Jr. National District, the APEX Museum is dedicated to telling the University), a Georgia Historical Society marker tells Administration, is the repository of information and Historical Park begins when you approach the Visitor story of the people of the African Diaspora and their the story of the Atlanta Student Movement that began historical materials from the Carter presidency. Browse Center, passing by the Civil Rights Walk of Fame with shoe contributions to America and the world. Visit the museum in 1960. The movement began when three Morehouse the museum’s photographs, videos and rotating material imprints of pioneers in the American civil rights movement to see art and photographic exhibits that celebrate the College students — Lonnie King, Joseph Pierce and Julian from the collection, and walk through a life-size replica noted in the pavement. Along the walk is a statue of complete history of African Americans. Bond — formed the Committee on the Appeal for Human of the Oval Office. Researchers can access the library Mahatma Gandhi with inscribed quotes from the India Rights and involved all the historically black institutions archives that include more than 27 million pages of leader who greatly influenced King’s nonviolent movement Hours: Tuesday - of the Atlanta University Center (AUC). -

Decatur Focus Newsletter, June 2021

City of Decatur Clear zone JUNE 2021 Volume 31 • Number 10 OFFICIAL PUBLICATION OFs THE CITY OF DECATUR, GEORGIA FCivil Rightsocu Trail Marker Unveiled MLK Marker Unveiling (L-R): Mike Warren, Muwali Davis, Dax Pettus, Fonta High, Katrina Walker, Genesis Reddicks, Mayor Emerita Elizabeth Wilson, Activist Charles Black, Mayor Pro Tem Tony Powers, and Dr. W. Todd Groce, President and CEO of Georgia Historical Society he Georgia Historical Society, in conjunction with students of Decatur High School, Beacon Hill Black Alliance for Human Rights, and the City of TDecatur, has announced the dedication of a new Civil Rights Trail historical marker in Decatur. The marker commemorates the sentencing of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. in Decatur to four months of hard labor following his arrest during the Atlanta Student Movement protest at Rich’s department store in October 1960. continued on page 6 CITY News City of Decatur The Decaturocu Focus is a joint publication of the sCity of Decatur,F the Decatur Downtown Development Author- STAY IN TOUCH ity and the Decatur Business Association. It is a newslet- ter intended to provide announcements and information related to events, activities, and businesses in the city of Decatur City Communications Decatur. The purpose of the newsletter is to promote the city and encourage the exchange of information among residents, business owners and the school system. Letters The City of Decatur uses various outlets to communicate with the community. to the editor, editorials or other opinion pieces are not Here are the primary ways in which the city communicates. published. All press releases, announcements and other information received for publication are subject to edit- ing.