The Relationship Between Loneliness, Self-Efficacy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

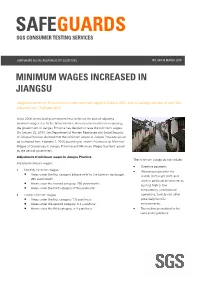

SGS-Safeguards 04910- Minimum Wages Increased in Jiangsu -EN-10

SAFEGUARDS SGS CONSUMER TESTING SERVICES CORPORATE SOCIAL RESPONSIILITY SOLUTIONS NO. 049/10 MARCH 2010 MINIMUM WAGES INCREASED IN JIANGSU Jiangsu becomes the first province to raise minimum wages in China in 2010, with an average increase of over 12% effective from 1 February 2010. Since 2008, many local governments have deferred the plan of adjusting minimum wages due to the financial crisis. As economic results are improving, the government of Jiangsu Province has decided to raise the minimum wages. On January 23, 2010, the Department of Human Resources and Social Security of Jiangsu Province declared that the minimum wages in Jiangsu Province would be increased from February 1, 2010 according to Interim Provisions on Minimum Wages of Enterprises in Jiangsu Province and Minimum Wages Standard issued by the central government. Adjustment of minimum wages in Jiangsu Province The minimum wages do not include: Adjusted minimum wages: • Overtime payment; • Monthly minimum wages: • Allowances given for the Areas under the first category (please refer to the table on next page): middle shift, night shift, and 960 yuan/month; work in particular environments Areas under the second category: 790 yuan/month; such as high or low Areas under the third category: 670 yuan/month temperature, underground • Hourly minimum wages: operations, toxicity and other Areas under the first category: 7.8 yuan/hour; potentially harmful Areas under the second category: 6.4 yuan/hour; environments; Areas under the third category: 5.4 yuan/hour. • The welfare prescribed in the laws and regulations. CORPORATE SOCIAL RESPONSIILITY SOLUTIONS NO. 049/10 MARCH 2010 P.2 Hourly minimum wages are calculated on the basis of the announced monthly minimum wages, taking into account: • The basic pension insurance premiums and the basic medical insurance premiums that shall be paid by the employers. -

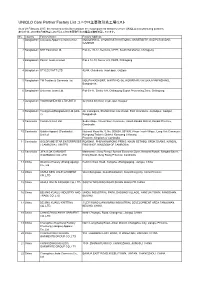

UNIQLO Core Partner Factory List ユニクロ主要取引先工場リスト

UNIQLO Core Partner Factory List ユニクロ主要取引先工場リスト As of 28 February 2017, the factories in this list constitute the major garment factories of core UNIQLO manufacturing partners. 本リストは、2017年2月末時点におけるユニクロ主要取引先の縫製工場を掲載しています。 No. Country Factory Name Factory Address 1 Bangladesh Colossus Apparel Limited unit 2 MOGORKHAL, CHOWRASTA NATIONAL UNIVERSITY, GAZIPUR SADAR, GAZIPUR 2 Bangladesh NHT Fashions Ltd. Plot no. 20-22, Sector-5, CEPZ, South Halishahar, Chittagong 3 Bangladesh Pacific Jeans Limited Plot # 14-19, Sector # 5, CEPZ, Chittagong 4 Bangladesh STYLECRAFT LTD 42/44, Chandona, Joydebpur, Gazipur 5 Bangladesh TM Textiles & Garments Ltd. MOUZA-KASHORE, WARD NO.-06, HOBIRBARI,VALUKA,MYMENSHING, Bangladesh. 6 Bangladesh Universal Jeans Ltd. Plot 09-11, Sector 6/A, Chittagong Export Processing Zone, Chittagong 7 Bangladesh YOUNGONES BD LTD UNIT-II 42 (3rd & 4th floor) Joydevpur, Gazipur 8 Bangladesh Youngones(Bangladesh) Ltd.(Unit- 24, Laxmipura, Shohid chan mia sharak, East Chandona, Joydebpur, Gazipur, 2) Bangladesh 9 Cambodia Cambo Unisoll Ltd. Seda village, Vihear Sour Commune, Ksach Kandal District, Kandal Province, Cambodia 10 Cambodia Golden Apparel (Cambodia) National Road No. 5, No. 005634, 001895, Phsar Trach Village, Long Vek Commune, Limited Kompong Tralarch District, Kompong Chhnang Province, Kingdom of Cambodia. 11 Cambodia GOLDFAME STAR ENTERPRISES ROAD#21, PHUM KAMPONG PRING, KHUM SETHBO, SROK SAANG, KANDAL ( CAMBODIA ) LIMITED PROVINCE, KINGDOM OF CAMBODIA 12 Cambodia JIFA S.OK GARMENT Manhattan ( Svay Rieng ) Special Economic Zone, National Road#, Sangkat Bavet, (CAMBODIA) CO.,LTD Krong Bavet, Svay Rieng Province, Cambodia 13 China Okamoto Hosiery (Zhangjiagang) Renmin West Road, Yangshe, Zhangjiagang, Jiangsu, China Co., Ltd 14 China ANHUI NEW JIALE GARMENT WenChangtown, XuanZhouDistrict, XuanCheng City, Anhui Province CO.,LTD 15 China ANHUI XINLIN FASHION CO.,LTD. -

Table of Codes for Each Court of Each Level

Table of Codes for Each Court of Each Level Corresponding Type Chinese Court Region Court Name Administrative Name Code Code Area Supreme People’s Court 最高人民法院 最高法 Higher People's Court of 北京市高级人民 Beijing 京 110000 1 Beijing Municipality 法院 Municipality No. 1 Intermediate People's 北京市第一中级 京 01 2 Court of Beijing Municipality 人民法院 Shijingshan Shijingshan District People’s 北京市石景山区 京 0107 110107 District of Beijing 1 Court of Beijing Municipality 人民法院 Municipality Haidian District of Haidian District People’s 北京市海淀区人 京 0108 110108 Beijing 1 Court of Beijing Municipality 民法院 Municipality Mentougou Mentougou District People’s 北京市门头沟区 京 0109 110109 District of Beijing 1 Court of Beijing Municipality 人民法院 Municipality Changping Changping District People’s 北京市昌平区人 京 0114 110114 District of Beijing 1 Court of Beijing Municipality 民法院 Municipality Yanqing County People’s 延庆县人民法院 京 0229 110229 Yanqing County 1 Court No. 2 Intermediate People's 北京市第二中级 京 02 2 Court of Beijing Municipality 人民法院 Dongcheng Dongcheng District People’s 北京市东城区人 京 0101 110101 District of Beijing 1 Court of Beijing Municipality 民法院 Municipality Xicheng District Xicheng District People’s 北京市西城区人 京 0102 110102 of Beijing 1 Court of Beijing Municipality 民法院 Municipality Fengtai District of Fengtai District People’s 北京市丰台区人 京 0106 110106 Beijing 1 Court of Beijing Municipality 民法院 Municipality 1 Fangshan District Fangshan District People’s 北京市房山区人 京 0111 110111 of Beijing 1 Court of Beijing Municipality 民法院 Municipality Daxing District of Daxing District People’s 北京市大兴区人 京 0115 -

Results Announcement for the Year Ended December 31, 2020

(GDR under the symbol "HTSC") RESULTS ANNOUNCEMENT FOR THE YEAR ENDED DECEMBER 31, 2020 The Board of Huatai Securities Co., Ltd. (the "Company") hereby announces the audited results of the Company and its subsidiaries for the year ended December 31, 2020. This announcement contains the full text of the annual results announcement of the Company for 2020. PUBLICATION OF THE ANNUAL RESULTS ANNOUNCEMENT AND THE ANNUAL REPORT This results announcement of the Company will be available on the website of London Stock Exchange (www.londonstockexchange.com), the website of National Storage Mechanism (data.fca.org.uk/#/nsm/nationalstoragemechanism), and the website of the Company (www.htsc.com.cn), respectively. The annual report of the Company for 2020 will be available on the website of London Stock Exchange (www.londonstockexchange.com), the website of the National Storage Mechanism (data.fca.org.uk/#/nsm/nationalstoragemechanism) and the website of the Company in due course on or before April 30, 2021. DEFINITIONS Unless the context otherwise requires, capitalized terms used in this announcement shall have the same meanings as those defined in the section headed “Definitions” in the annual report of the Company for 2020 as set out in this announcement. By order of the Board Zhang Hui Joint Company Secretary Jiangsu, the PRC, March 23, 2021 CONTENTS Important Notice ........................................................... 3 Definitions ............................................................... 6 CEO’s Letter .............................................................. 11 Company Profile ........................................................... 15 Summary of the Company’s Business ........................................... 27 Management Discussion and Analysis and Report of the Board ....................... 40 Major Events.............................................................. 112 Changes in Ordinary Shares and Shareholders .................................... 149 Directors, Supervisors, Senior Management and Staff.............................. -

Transmissibility of Hand, Foot, and Mouth Disease in 97 Counties of Jiangsu Province, China, 2015- 2020

Transmissibility of Hand, Foot, and Mouth Disease in 97 Counties of Jiangsu Province, China, 2015- 2020 Wei Zhang Xiamen University Jia Rui Xiamen University Xiaoqing Cheng Jiangsu Provincial Center for Disease Control and Prevention Bin Deng Xiamen University Hesong Zhang Xiamen University Lijing Huang Xiamen University Lexin Zhang Xiamen University Simiao Zuo Xiamen University Junru Li Xiamen University XingCheng Huang Xiamen University Yanhua Su Xiamen University Benhua Zhao Xiamen University Yan Niu Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention, Beijing City, People’s Republic of China Hongwei Li Xiamen University Jian-li Hu Jiangsu Provincial Center for Disease Control and Prevention Tianmu Chen ( [email protected] ) Page 1/30 Xiamen University Research Article Keywords: Hand foot mouth disease, Jiangsu Province, model, transmissibility, effective reproduction number Posted Date: July 30th, 2021 DOI: https://doi.org/10.21203/rs.3.rs-752604/v1 License: This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Read Full License Page 2/30 Abstract Background: Hand, foot, and mouth disease (HFMD) has been a serious disease burden in the Asia Pacic region represented by China, and the transmission characteristics of HFMD in regions haven’t been clear. This study calculated the transmissibility of HFMD at county levels in Jiangsu Province, China, analyzed the differences of transmissibility and explored the reasons. Methods: We built susceptible-exposed-infectious-asymptomatic-removed (SEIAR) model for seasonal characteristics of HFMD, estimated effective reproduction number (Reff) by tting the incidence of HFMD in 97 counties of Jiangsu Province from 2015 to 2020, compared incidence rate and transmissibility in different counties by non -parametric test, rapid cluster analysis and rank-sum ratio. -

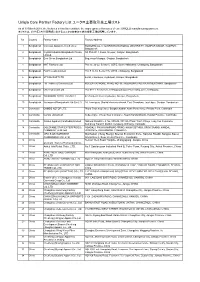

Uniqlo Core Partner Factory List ユニクロ主要取引先工場リスト

Uniqlo Core Partner Factory List ユニクロ主要取引先工場リスト As of 30 March 2018, the factories in this list constitute the major garment factories of core UNIQLO manufacturing partners. 本リストは、2018年3月30日時点におけるユニクロ主要取引先の縫製工場を掲載しています。 No. Country Factory Name Factory Address 1 Bangladesh Colossus Apparel Limited unit 2 MOGORKHAL, CHOWRASTA NATIONAL UNIVERSITY, GAZIPUR SADAR, GAZIPUR, Bangladesh 2 Bangladesh Crystal Industrial Bangladesh Private SA Plot-2013, Kewa, Sreepur, Gazipur, Bangladesh Limited. 3 Bangladesh Ever Smart Bangladesh Ltd. Begumour Mirzapur, Gazipur, Bangladesh 4 Bangladesh NHT Fashions Ltd. Plot no. 20-22, Sector-5, CEPZ, South Halishahar, Chittagong, Bangladesh 5 Bangladesh Pacific Jeans Limited Plot # 14-19, Sector # 5, CEPZ, Chittagong, Bangladesh 6 Bangladesh STYLECRAFT LTD 42/44, Chandona, Joydebpur, Gazipur, Bangladesh 7 Bangladesh TM Textiles & Garments Ltd. MOUZA-KASHORE, WARD NO.-06, HOBIRBARI,VALUKA,MYMENSHING, Bangladesh 8 Bangladesh Universal Jeans Ltd. Plot 09-11, Sector 6/A, Chittagong Export Processing Zone, Chittagong 9 Bangladesh YOUNGONES BD LTD UNIT-II 42 (3rd & 4th floor) Joydevpur, Gazipur, Bangladesh 10 Bangladesh Youngones(Bangladesh) Ltd.(Unit-2) 24, Laxmipura, Shohid chan mia sharak, East Chandona, Joydebpur, Gazipur, Bangladesh 11 Cambodia CAMBO KOTOP LTD. Phum Trapeang Chrey, Sangkat Kakab, Khan Porsenchey, Phnom Penh, Cambodia. 12 Cambodia Cambo Unisoll Ltd. Seda village, Vihear Sour Commune, Ksach Kandal District, Kandal Province, Cambodia 13 Cambodia Golden Apparel (Cambodia) Limited National Road No. -

List of Main Production Facilities of ALDI Nord's Suppliers for Apparel

List of Main Production Facilities of ALDI Nord‘s Suppliers for Apparel, Home Textiles and Shoes Version: April 2021 Produktionsstättenliste | März 2018 | Seite 0/17 Name Address Number of Employees Commodity Group Bangladesh AB Apparels Ltd. 225, Singair Road, Tetuljhora, Hemayetpur 2001 - 5000 Garment textiles Ador Composite Ltd. 1, C & B Bazar, Gilarchala, Sreepur 1001 - 2000 Garment textiles AKH Eco Apparels Ltd. 495, Balitha, Shahbelishwar, Dhamrai 5001 - 10000 Garment textiles Angshuk Ltd. 133-134, Hamayetpur, Savar 501 - 1000 Garment textiles Apparels Village Ltd. Khagan, Birulia, Savar 2001 - 5000 Garment textiles Aspire Garments Ltd. 491, Dhalla, Singair 2001 - 5000 Garment textiles B.H.I.S. Apparels Ltd. 671, Datta Para, Hossain Market, Tongi 2001 - 5000 Garment textiles Blue Planet Knitwear Ltd. Mulaid, P.O.: Tengra, Sreepur 1001 - 2000 Garment textiles Chaity Composite Ltd. Chotto Silmondi, Tripurdi, Sonargaon 5001 - 10000 Garment textiles Chantik Garments Ltd. Kumkumari, Gouripur, Ashulia, Savar 2001 - 5000 Garment textiles Chorka Textile Ltd. Kajirchor, Danga Bazar, Polash 2001 - 5000 Garment textiles Citadel Apparels Ltd. Joy Bangla Road, Kunia, K.B. Bazar, Gazipur Sadar 501 - 1000 Garment textiles Cotton Dyeing & Finishing Mills Ltd. Vill: Amtoli, Union: 10 No. Habirbari, P.O-Seedstore Bazar, P.S.-Valuka 1001 - 2000 Garment textiles Crossline Factory (Pvt) Ltd. 25, Vadam, Uttarpara, Nishatnagar, Tongi 1001 - 2000 Garment textiles Plot No. 45, 48, 49, 51 & 52; Holding No.: 3/C, Vadam, P.O.: Crossline Knit Fabrics Ltd. 1001 - 2000 Garment textiles Nishatnagar, Tongi, Gazipur-1711, Gazipur Crown Exclusive Wears Ltd. Mawna, Sreepur 2001 - 5000 Garment textiles Crown Fashion & Sweater Industries Ltd. Plot No. 781-782, Vogra, Joydebpur, Gazipur-1704 2001 - 5000 Garment textiles Denim Fashions Ltd. -

Spatial and Temporal Evaluation of Ecological Footprint Intensity of Jiangsu Province at the County-Level Scale

International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health Article Spatial and Temporal Evaluation of Ecological Footprint Intensity of Jiangsu Province at the County-Level Scale Decun Wu 1 and Jinping Liu 2,* 1 School of Public Administration and Sociology, Jiangsu Normal University, Xuzhou 221116, China; [email protected] 2 School of Economics and Management, China University of Mining and Technology, Xuzhou 221116, China * Correspondence: [email protected] Received: 10 September 2020; Accepted: 23 October 2020; Published: 26 October 2020 Abstract: Due to the high ecological pressure that exists in the process of rapid economic development in Jiangsu Province, it is necessary to evaluate its ecological footprint intensity (EFI). This article focuses on ecological footprint intensity analysis at the county scale. We used county-level data to evaluate the spatial distributions and temporal trends of the ecological footprint intensity in Jiangsu’s counties from 1995 to 2015. The temporal trends of counties are divided into five types: linear declining type, N-shape type, inverted-N type, U-shape type and inverted-U shape type. It was discovered that the proportions of the carbon footprint intensity were maintained or increased in most counties. Exploratory spatial data analysis shows that there was a certain regularity of the EFI spatial distributions, i.e., a gradient decrease from north to south, and there was a decline in the spatial heterogeneity of EFI in Jiangsu’s counties over time. The global Moran’s index (Moran’s I) and local spatial association index (LISA) are used to analyze both the global and local spatial correlation of EFIs among counties of Jiangsu Province. -

Promotion of Qiu He Raises Questions About Direction of Reform

Fewsmith, China Leadership Monitor, No. 17 Promotion of Qiu He Raises Questions about Direction of Reform Joseph Fewsmith For the last two years, the Chinese media have widely discussed the ‘Qiu He Phenomenon,’ attempting to understand the significance of a local county party secretary’s using autocratic methods to jump-start the economy of Jiangsu’s poorest county. Qiu He has been both praised and criticized; now he has been promoted to vice governor of Jiangsu, and at 50 years of age he could rise farther in China’s political system. So, whereas promotions to vice governships rarely raise eyebrows, Qiu He’s promotion has been widely discussed. Known as an “official with personality” (gexing guanyuan), Qiu He stands out among the ranks of China’s generally staid bureaucracy and makes us think about what types of officials might be promoted under Hu Jintao and what this means for the building of institutions in China. On January 20, the Xinhua News Agency reported that Zhang Jiuhan and Qiu He had been elected vice governors of Jiangsu Province. Zhang’s election raised no eyebrows. His career reflects a steady climb through the ranks, though his long experience in the provincial Communist Youth League (CYL) suggests the ever-increasing importance of that group as a route to career advancement. Born in 1950 in Jiangdu City, on the north bank of the Yangzi River just east of Yangzhou (the city where Jiang Zemin was raised), Zhang began work in 1970 on a branch farm of the Laoshan tree farm (linchang), and he has spent most of the rest of his career in agriculture. -

Policy Note on Integrated Flood Risk Management Key Lesson Learned and Recommendations for China

Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Strategy Resources Partnership China CountryWater WATER PARTNERSHIP PROGRAM PARTNERSHIP WATER THE WORLDBANK (2013-2020) China Country Water Resources Partnership Strategy © 2013 The World Bank 1818 H Street NW Washington DC 20433 Telephone: 202-473-1000 Internet: www.worldbank.org This work is a product of the staff of The World Bank with external contributions. The findings, interpretations, and conclusions expressed in this work do not necessarily reflect the views of The World Bank, its Board of Executive Directors or the governments they represent. The World Bank does not guarantee the accuracy of the data included in this work. The boundaries, colors, denominations, and other information shown on any map in this work do not imply any judgment on the part of The World Bank concerning the legal status of any territory or the endorsement or acceptance of such boundaries. Rights and Permissions The material in this work is subject to copyright. Because The World Bank encourages dissemination of its knowledge, this work may be reproduced, in whole or in part, for noncommercial purposes as long as full attribution to this work is given. Any queries on rights and licenses, including subsidiary rights, should be addressed to the Office of the Publisher, The World Bank, 1818 H Street NW, Washington, DC 20433, USA; fax: 202-522-2422; e-mail: [email protected]. Table of Contents ACKNOWLEDGMENTS ..................................................................................................................VII -

Global Factory List As of August 3Rd, 2020

Global Factory List as of August 3rd, 2020 Target is committed to providing increased supply chain transparency. To meet this objective, Target publishes a list of all tier one factories that produce our owned-brand products, national brand products where Target is the importer of record, as well as tier two apparel textile mills and wet processing facilities. Target partners with its vendors and suppliers to maintain an accurate factory list. The list below represents factories as of August 3rd, 2020. This list is subject to change and updates will be provided on a quarterly basis. Factory Name State/Province City Address AMERICAN SAMOA American Samoa Plant Pago Pago 368 Route 1,Tutuila Island ARGENTINA Angel Estrada Cla. S.A, Buenos Aires Ciudad de Buenos Aires Ruta Nacional N 38 Km. 1,155,Provincia de La Rioja AUSTRIA Tiroler Glashuette GmbH Werk: Schneegattern Oberosterreich Lengau Kobernauserwaldstrase 25, BAHRAIN WestPoint Home Bahrain W.L.L. Al Manamah (Al Asimah) Riffa Building #1912, Road # 5146, Block 951,South Alba Industrial Area, Askar BANGLADESH Campex (BD) Limited Chittagong zila Chattogram Building-FS SFB#06, Sector#01, Road#02, Chittagong Export Processing Zone,, Canvas Garments (Pvt.) Ltd Chittagong zila Chattogram 301, North Baizid Bostami Road,,Nasirabad I/A, Canvas Building Chittagong Asian Apparels Chittagong zila Chattogram 132 Nasirabad Indstrial Area,Chattogram Clifton Cotton Mills Ltd Chittagong zila Chattogram CDA plot no-D28,28-d/2 Char Ragmatia Kalurghat, Clifton Textile Chittagong zila Chattogram 180 Nasirabad Industrial Area,Baizid Bostami Road Fashion Watch Limited Chittagong zila Chattogram 1363/A 1364 Askarabad, D.T. Road,Doublemoring, Chattogram, Bangladesh Fortune Apparels Ltd Chittagong zila Chattogram 135/142 Nasirabad Industrial Area,Chattogram KDS Garment Industries Ltd. -

Subsidy Programs

SUBSIDIES REQUEST FROM THE UNITED STATES TO CHINA PURSUANT TO ARTICLE 25.10 OF THE AGREEMENT The following communication, dated 15 April 2016, is being circulated at the request of the Delegation of the United States. _______________ In the report that it prepared for China's most recent Trade Policy Review, held in July 2014, the Secretariat included information that it had uncovered on 30 support programs for China's fisheries sector.1 The Secretariat's Report noted that China had not notified any of these support programs to the Committee on Subsidies and Countervailing Measures (Committee) and that China could not verify any of the information provided to it by the Secretariat. During the ensuing Trade Policy Review meetings, China responded to Members' questions about these support programs by stating that it needed more time to identify and verify information regarding these support programs. In April of last year, the United States submitted questions to China with respect to these programs and other fishery support measures the United States had uncovered through its own efforts.2 Once again, despite its obligation under Article 25.9 of the Agreement to provide answers "as quickly as possible and in a comprehensive manner", China to date has not meaningfully responded to the United States' request and has refused repeated requests to meet bilaterally to discuss the issue, and the issue of subsidy notifications more generally. In November of last year, China submitted its latest subsidy notification covering the period 2009 through 2014.3 In this notification, China did not include: (1) any of the fishery subsidy programs identified in China's 2014 TPR report, (2) any of the additional measures identified by the United States in its Article 25.8 submission or (3) any of the fisheries subsidies measures identified in the 2014 Article 25.10 submission of the United States4.