Promotion of Qiu He Raises Questions About Direction of Reform

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

How China's Leaders Think: the Inside Story of China's Past, Current

bindex.indd 540 3/14/11 3:26:49 PM China’s development, at least in part, is driven by patriotism and pride. The Chinese people have made great contributions to world civilization. Our commitment and determination is rooted in our historic and national pride. It’s fair to say that we have achieved some successes, [nevertheless] we should have a cautious appraisal of our accomplishments. We should never overestimate our accomplish- ments or indulge ourselves in our achievements. We need to assess ourselves objectively. [and aspire to] our next higher goal. [which is] a persistent and unremitting process. Xi Jinping Politburo Standing Committee member In the face of complex and ever-changing international and domes- tic environments, the Chinese Government promptly and decisively adjusted our macroeconomic policies and launched a comprehensive stimulus package to ensure stable and rapid economic growth. We increased government spending and public investments and imple- mented structural tax reductions. Balancing short-term and long- term strategic perspectives, we are promoting industrial restructuring and technological innovation, and using principles of reform to solve problems of development. Li Keqiang Politburo Standing Committee member I am now serving my second term in the Politburo. President Hu Jintao’s character is modest and low profile. we all have the high- est respect and admiration for him—for his leadership, perspicacity and moral convictions. Under his leadership, complex problems can all get resolved. It takes vision to avoid major conflicts in soci- ety. Income disparities, unemployment, bureaucracy and corruption could cause instability. This is the Party’s most severe test. -

April 12, 1967 Discussion Between Zhou Enlai, Chen Yi, Pham Van Dong and Vo Nguyen Giap

Digital Archive digitalarchive.wilsoncenter.org International History Declassified April 12, 1967 Discussion between Zhou Enlai, Chen Yi, Pham Van Dong and Vo Nguyen Giap Citation: “Discussion between Zhou Enlai, Chen Yi, Pham Van Dong and Vo Nguyen Giap,” April 12, 1967, History and Public Policy Program Digital Archive, CWIHP Working Paper 22, "77 Conversations." http://digitalarchive.wilsoncenter.org/document/112156 Summary: Zhou Enlai discusses the class struggle present in China. Original Language: Chinese Contents: English Translation ZHOU ENLAI, CHEN YI AND PHAM VAN DONG, VO NGUYEN GIAP Beijing, 12 April 1967 Zhou Enlai: …In the past ten years, we were conducting another war, a bloodless one: a class struggle. But, it is a matter of fact that among our generals, there are some, [although] not all, who knew very well how to conduct a bloody war, [but] now don’t know how to conduct a bloodless one. They even look down on the masses. The other day while we were on board the plane, I told you that our cultural revolution this time was aimed at overthrowing a group of ruling people in the party who wanted to follow the capitalist path. It was also aimed at destroying the old forces, the old culture, the old ideology, the old customs that were not suitable to the socialist revolution. In one of his speeches last year, Comrade Lin Biao said: In the process of socialist revolution, we have to destroy the “private ownership” of the bourgeoisie, and to construct the “public ownership” of the proletariat. So, for the introduction of the “public ownership” system, who do you rely on? Based on the experience in the 17 years after liberation, Comrade Mao Zedong holds that after seizing power, the proletariat should eliminate the “private ownership” of the bourgeoisie. -

Hong Kong SAR

China Data Supplement November 2006 J People’s Republic of China J Hong Kong SAR J Macau SAR J Taiwan ISSN 0943-7533 China aktuell Data Supplement – PRC, Hong Kong SAR, Macau SAR, Taiwan 1 Contents The Main National Leadership of the PRC 2 LIU Jen-Kai The Main Provincial Leadership of the PRC 30 LIU Jen-Kai Data on Changes in PRC Main Leadership 37 LIU Jen-Kai PRC Agreements with Foreign Countries 47 LIU Jen-Kai PRC Laws and Regulations 50 LIU Jen-Kai Hong Kong SAR 54 Political, Social and Economic Data LIU Jen-Kai Macau SAR 61 Political, Social and Economic Data LIU Jen-Kai Taiwan 65 Political, Social and Economic Data LIU Jen-Kai ISSN 0943-7533 All information given here is derived from generally accessible sources. Publisher/Distributor: GIGA Institute of Asian Affairs Rothenbaumchaussee 32 20148 Hamburg Germany Phone: +49 (0 40) 42 88 74-0 Fax: +49 (040) 4107945 2 November 2006 The Main National Leadership of the PRC LIU Jen-Kai Abbreviations and Explanatory Notes CCP CC Chinese Communist Party Central Committee CCa Central Committee, alternate member CCm Central Committee, member CCSm Central Committee Secretariat, member PBa Politburo, alternate member PBm Politburo, member Cdr. Commander Chp. Chairperson CPPCC Chinese People’s Political Consultative Conference CYL Communist Youth League Dep. P.C. Deputy Political Commissar Dir. Director exec. executive f female Gen.Man. General Manager Gen.Sec. General Secretary Hon.Chp. Honorary Chairperson H.V.-Chp. Honorary Vice-Chairperson MPC Municipal People’s Congress NPC National People’s Congress PCC Political Consultative Conference PLA People’s Liberation Army Pol.Com. -

SGS-Safeguards 04910- Minimum Wages Increased in Jiangsu -EN-10

SAFEGUARDS SGS CONSUMER TESTING SERVICES CORPORATE SOCIAL RESPONSIILITY SOLUTIONS NO. 049/10 MARCH 2010 MINIMUM WAGES INCREASED IN JIANGSU Jiangsu becomes the first province to raise minimum wages in China in 2010, with an average increase of over 12% effective from 1 February 2010. Since 2008, many local governments have deferred the plan of adjusting minimum wages due to the financial crisis. As economic results are improving, the government of Jiangsu Province has decided to raise the minimum wages. On January 23, 2010, the Department of Human Resources and Social Security of Jiangsu Province declared that the minimum wages in Jiangsu Province would be increased from February 1, 2010 according to Interim Provisions on Minimum Wages of Enterprises in Jiangsu Province and Minimum Wages Standard issued by the central government. Adjustment of minimum wages in Jiangsu Province The minimum wages do not include: Adjusted minimum wages: • Overtime payment; • Monthly minimum wages: • Allowances given for the Areas under the first category (please refer to the table on next page): middle shift, night shift, and 960 yuan/month; work in particular environments Areas under the second category: 790 yuan/month; such as high or low Areas under the third category: 670 yuan/month temperature, underground • Hourly minimum wages: operations, toxicity and other Areas under the first category: 7.8 yuan/hour; potentially harmful Areas under the second category: 6.4 yuan/hour; environments; Areas under the third category: 5.4 yuan/hour. • The welfare prescribed in the laws and regulations. CORPORATE SOCIAL RESPONSIILITY SOLUTIONS NO. 049/10 MARCH 2010 P.2 Hourly minimum wages are calculated on the basis of the announced monthly minimum wages, taking into account: • The basic pension insurance premiums and the basic medical insurance premiums that shall be paid by the employers. -

Journal of Current Chinese Affairs

3/2006 Data Supplement PR China Hong Kong SAR Macau SAR Taiwan CHINA aktuell Journal of Current Chinese Affairs Data Supplement People’s Republic of China, Hong Kong SAR, Macau SAR, Taiwan ISSN 0943-7533 All information given here is derived from generally accessible sources. Publisher/Distributor: Institute of Asian Affairs Rothenbaumchaussee 32 20148 Hamburg Germany Phone: (0 40) 42 88 74-0 Fax:(040)4107945 Contributors: Uwe Kotzel Dr. Liu Jen-Kai Christine Reinking Dr. Günter Schucher Dr. Margot Schüller Contents The Main National Leadership of the PRC LIU JEN-KAI 3 The Main Provincial Leadership of the PRC LIU JEN-KAI 22 Data on Changes in PRC Main Leadership LIU JEN-KAI 27 PRC Agreements with Foreign Countries LIU JEN-KAI 30 PRC Laws and Regulations LIU JEN-KAI 34 Hong Kong SAR Political Data LIU JEN-KAI 36 Macau SAR Political Data LIU JEN-KAI 39 Taiwan Political Data LIU JEN-KAI 41 Bibliography of Articles on the PRC, Hong Kong SAR, Macau SAR, and on Taiwan UWE KOTZEL / LIU JEN-KAI / CHRISTINE REINKING / GÜNTER SCHUCHER 43 CHINA aktuell Data Supplement - 3 - 3/2006 Dep.Dir.: CHINESE COMMUNIST Li Jianhua 03/07 PARTY Li Zhiyong 05/07 The Main National Ouyang Song 05/08 Shen Yueyue (f) CCa 03/01 Leadership of the Sun Xiaoqun 00/08 Wang Dongming 02/10 CCP CC General Secretary Zhang Bolin (exec.) 98/03 PRC Hu Jintao 02/11 Zhao Hongzhu (exec.) 00/10 Zhao Zongnai 00/10 Liu Jen-Kai POLITBURO Sec.-Gen.: Li Zhiyong 01/03 Standing Committee Members Propaganda (Publicity) Department Hu Jintao 92/10 Dir.: Liu Yunshan PBm CCSm 02/10 Huang Ju 02/11 -

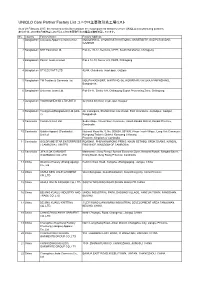

UNIQLO Core Partner Factory List ユニクロ主要取引先工場リスト

UNIQLO Core Partner Factory List ユニクロ主要取引先工場リスト As of 28 February 2017, the factories in this list constitute the major garment factories of core UNIQLO manufacturing partners. 本リストは、2017年2月末時点におけるユニクロ主要取引先の縫製工場を掲載しています。 No. Country Factory Name Factory Address 1 Bangladesh Colossus Apparel Limited unit 2 MOGORKHAL, CHOWRASTA NATIONAL UNIVERSITY, GAZIPUR SADAR, GAZIPUR 2 Bangladesh NHT Fashions Ltd. Plot no. 20-22, Sector-5, CEPZ, South Halishahar, Chittagong 3 Bangladesh Pacific Jeans Limited Plot # 14-19, Sector # 5, CEPZ, Chittagong 4 Bangladesh STYLECRAFT LTD 42/44, Chandona, Joydebpur, Gazipur 5 Bangladesh TM Textiles & Garments Ltd. MOUZA-KASHORE, WARD NO.-06, HOBIRBARI,VALUKA,MYMENSHING, Bangladesh. 6 Bangladesh Universal Jeans Ltd. Plot 09-11, Sector 6/A, Chittagong Export Processing Zone, Chittagong 7 Bangladesh YOUNGONES BD LTD UNIT-II 42 (3rd & 4th floor) Joydevpur, Gazipur 8 Bangladesh Youngones(Bangladesh) Ltd.(Unit- 24, Laxmipura, Shohid chan mia sharak, East Chandona, Joydebpur, Gazipur, 2) Bangladesh 9 Cambodia Cambo Unisoll Ltd. Seda village, Vihear Sour Commune, Ksach Kandal District, Kandal Province, Cambodia 10 Cambodia Golden Apparel (Cambodia) National Road No. 5, No. 005634, 001895, Phsar Trach Village, Long Vek Commune, Limited Kompong Tralarch District, Kompong Chhnang Province, Kingdom of Cambodia. 11 Cambodia GOLDFAME STAR ENTERPRISES ROAD#21, PHUM KAMPONG PRING, KHUM SETHBO, SROK SAANG, KANDAL ( CAMBODIA ) LIMITED PROVINCE, KINGDOM OF CAMBODIA 12 Cambodia JIFA S.OK GARMENT Manhattan ( Svay Rieng ) Special Economic Zone, National Road#, Sangkat Bavet, (CAMBODIA) CO.,LTD Krong Bavet, Svay Rieng Province, Cambodia 13 China Okamoto Hosiery (Zhangjiagang) Renmin West Road, Yangshe, Zhangjiagang, Jiangsu, China Co., Ltd 14 China ANHUI NEW JIALE GARMENT WenChangtown, XuanZhouDistrict, XuanCheng City, Anhui Province CO.,LTD 15 China ANHUI XINLIN FASHION CO.,LTD. -

Table of Codes for Each Court of Each Level

Table of Codes for Each Court of Each Level Corresponding Type Chinese Court Region Court Name Administrative Name Code Code Area Supreme People’s Court 最高人民法院 最高法 Higher People's Court of 北京市高级人民 Beijing 京 110000 1 Beijing Municipality 法院 Municipality No. 1 Intermediate People's 北京市第一中级 京 01 2 Court of Beijing Municipality 人民法院 Shijingshan Shijingshan District People’s 北京市石景山区 京 0107 110107 District of Beijing 1 Court of Beijing Municipality 人民法院 Municipality Haidian District of Haidian District People’s 北京市海淀区人 京 0108 110108 Beijing 1 Court of Beijing Municipality 民法院 Municipality Mentougou Mentougou District People’s 北京市门头沟区 京 0109 110109 District of Beijing 1 Court of Beijing Municipality 人民法院 Municipality Changping Changping District People’s 北京市昌平区人 京 0114 110114 District of Beijing 1 Court of Beijing Municipality 民法院 Municipality Yanqing County People’s 延庆县人民法院 京 0229 110229 Yanqing County 1 Court No. 2 Intermediate People's 北京市第二中级 京 02 2 Court of Beijing Municipality 人民法院 Dongcheng Dongcheng District People’s 北京市东城区人 京 0101 110101 District of Beijing 1 Court of Beijing Municipality 民法院 Municipality Xicheng District Xicheng District People’s 北京市西城区人 京 0102 110102 of Beijing 1 Court of Beijing Municipality 民法院 Municipality Fengtai District of Fengtai District People’s 北京市丰台区人 京 0106 110106 Beijing 1 Court of Beijing Municipality 民法院 Municipality 1 Fangshan District Fangshan District People’s 北京市房山区人 京 0111 110111 of Beijing 1 Court of Beijing Municipality 民法院 Municipality Daxing District of Daxing District People’s 北京市大兴区人 京 0115 -

Journal of Current Chinese Affairs

China Data Supplement October 2006 J People’s Republic of China J Hong Kong SAR J Macau SAR J Taiwan ISSN 0943-7533 China aktuell Data Supplement – PRC, Hong Kong SAR, Macau SAR, Taiwan 1 Contents The Main National Leadership of the PRC 2 LIU Jen-Kai The Main Provincial Leadership of the PRC 30 LIU Jen-Kai Data on Changes in PRC Main Leadership 37 LIU Jen-Kai PRC Agreements with Foreign Countries 44 LIU Jen-Kai PRC Laws and Regulations 48 LIU Jen-Kai Hong Kong SAR 49 Political, Social and Economic Data LIU Jen-Kai Macau SAR 56 Political, Social and Economic Data LIU Jen-Kai Taiwan 60 Political, Social and Economic Data LIU Jen-Kai ISSN 0943-7533 All information given here is derived from generally accessible sources. Publisher/Distributor: GIGA Institute of Asian Affairs Rothenbaumchaussee 32 20148 Hamburg Germany Phone: +49 (0 40) 42 88 74-0 Fax: +49 (040) 4107945 2 October 2006 The Main National Leadership of the PRC LIU Jen-Kai Abbreviations and Explanatory Notes CCP CC Chinese Communist Party Central Committee CCa Central Committee, alternate member CCm Central Committee, member CCSm Central Committee Secretariat, member PBa Politburo, alternate member PBm Politburo, member Cdr. Commander Chp. Chairperson CPPCC Chinese People’s Political Consultative Conference CYL Communist Youth League Dep. P.C. Deputy Political Commissar Dir. Director exec. executive f female Gen.Man. General Manager Gen.Sec. General Secretary Hon.Chp. Honorary Chairperson H.V.-Chp. Honorary Vice-Chairperson MPC Municipal People’s Congress NPC National People’s Congress PCC Political Consultative Conference PLA People’s Liberation Army Pol.Com. -

Results Announcement for the Year Ended December 31, 2020

(GDR under the symbol "HTSC") RESULTS ANNOUNCEMENT FOR THE YEAR ENDED DECEMBER 31, 2020 The Board of Huatai Securities Co., Ltd. (the "Company") hereby announces the audited results of the Company and its subsidiaries for the year ended December 31, 2020. This announcement contains the full text of the annual results announcement of the Company for 2020. PUBLICATION OF THE ANNUAL RESULTS ANNOUNCEMENT AND THE ANNUAL REPORT This results announcement of the Company will be available on the website of London Stock Exchange (www.londonstockexchange.com), the website of National Storage Mechanism (data.fca.org.uk/#/nsm/nationalstoragemechanism), and the website of the Company (www.htsc.com.cn), respectively. The annual report of the Company for 2020 will be available on the website of London Stock Exchange (www.londonstockexchange.com), the website of the National Storage Mechanism (data.fca.org.uk/#/nsm/nationalstoragemechanism) and the website of the Company in due course on or before April 30, 2021. DEFINITIONS Unless the context otherwise requires, capitalized terms used in this announcement shall have the same meanings as those defined in the section headed “Definitions” in the annual report of the Company for 2020 as set out in this announcement. By order of the Board Zhang Hui Joint Company Secretary Jiangsu, the PRC, March 23, 2021 CONTENTS Important Notice ........................................................... 3 Definitions ............................................................... 6 CEO’s Letter .............................................................. 11 Company Profile ........................................................... 15 Summary of the Company’s Business ........................................... 27 Management Discussion and Analysis and Report of the Board ....................... 40 Major Events.............................................................. 112 Changes in Ordinary Shares and Shareholders .................................... 149 Directors, Supervisors, Senior Management and Staff.............................. -

Chinese Politics in the Xi Jingping Era: Reassessing Collective Leadership

CHAPTER 1 Governance Collective Leadership Revisited Th ings don’t have to be or look identical in order to be balanced or equal. ڄ Maya Lin — his book examines how the structure and dynamics of the leadership of Tthe Chinese Communist Party (CCP) have evolved in response to the chal- lenges the party has confronted since the late 1990s. Th is study pays special attention to the issue of leadership se lection and composition, which is a per- petual concern in Chinese politics. Using both quantitative and qualitative analyses, this volume assesses the changing nature of elite recruitment, the generational attributes of the leadership, the checks and balances between competing po liti cal co ali tions or factions, the behavioral patterns and insti- tutional constraints of heavyweight politicians in the collective leadership, and the interplay between elite politics and broad changes in Chinese society. Th is study also links new trends in elite politics to emerging currents within the Chinese intellectual discourse on the tension between strongman politics and collective leadership and its implications for po liti cal reforms. A systematic analy sis of these developments— and some seeming contradictions— will help shed valuable light on how the world’s most populous country will be governed in the remaining years of the Xi Jinping era and beyond. Th is study argues that the survival of the CCP regime in the wake of major po liti cal crises such as the Bo Xilai episode and rampant offi cial cor- ruption is not due to “authoritarian resilience”— the capacity of the Chinese communist system to resist po liti cal and institutional changes—as some foreign China analysts have theorized. -

Transmissibility of Hand, Foot, and Mouth Disease in 97 Counties of Jiangsu Province, China, 2015- 2020

Transmissibility of Hand, Foot, and Mouth Disease in 97 Counties of Jiangsu Province, China, 2015- 2020 Wei Zhang Xiamen University Jia Rui Xiamen University Xiaoqing Cheng Jiangsu Provincial Center for Disease Control and Prevention Bin Deng Xiamen University Hesong Zhang Xiamen University Lijing Huang Xiamen University Lexin Zhang Xiamen University Simiao Zuo Xiamen University Junru Li Xiamen University XingCheng Huang Xiamen University Yanhua Su Xiamen University Benhua Zhao Xiamen University Yan Niu Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention, Beijing City, People’s Republic of China Hongwei Li Xiamen University Jian-li Hu Jiangsu Provincial Center for Disease Control and Prevention Tianmu Chen ( [email protected] ) Page 1/30 Xiamen University Research Article Keywords: Hand foot mouth disease, Jiangsu Province, model, transmissibility, effective reproduction number Posted Date: July 30th, 2021 DOI: https://doi.org/10.21203/rs.3.rs-752604/v1 License: This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Read Full License Page 2/30 Abstract Background: Hand, foot, and mouth disease (HFMD) has been a serious disease burden in the Asia Pacic region represented by China, and the transmission characteristics of HFMD in regions haven’t been clear. This study calculated the transmissibility of HFMD at county levels in Jiangsu Province, China, analyzed the differences of transmissibility and explored the reasons. Methods: We built susceptible-exposed-infectious-asymptomatic-removed (SEIAR) model for seasonal characteristics of HFMD, estimated effective reproduction number (Reff) by tting the incidence of HFMD in 97 counties of Jiangsu Province from 2015 to 2020, compared incidence rate and transmissibility in different counties by non -parametric test, rapid cluster analysis and rank-sum ratio. -

Download the Publication

WOODROW WILSON INTERNATIONAL CENTER FOR SCHOLARS Lee H. Hamilton, 77 CONVERSATIONS Christian Ostermann, Director Director Between Chinese and Foreign Leaders on the Wars in Indochina, 1964-1977 BOARD OF TRUSTEES: ADVISORY Edited by COMMITTEE: Joseph A. Cari, Jr., Chairman Odd Arne Westad, Chen Jian, Stein Tønnesson, William Taubman Steven Alan Bennett, (Amherst College) Nguyen Vu Tungand and James G. Hershberg Vice Chairman Chairman PUBLIC MEMBERS Working Paper No. 22 Michael Beschloss The Secretary of State (Historian, Author) Colin Powell; The Librarian of Congress James H. Billington James H. Billington; (Librarian of Congress) The Archivist of the United States John W. Carlin; Warren I. Cohen (University of Maryland- The Chairman of the National Endowment Baltimore) for the Humanities Bruce Cole; The Secretary of the John Lewis Gaddis Smithsonian Institution (Yale University) Lawrence M. Small; The Secretary of Education James Hershberg Roderick R. Paige; (The George Washington The Secretary of Health University) & Human Services Tommy G. Thompson; Washington, D.C. Samuel F. Wells, Jr. PRIVATE MEMBERS (Woodrow Wilson Center) Carol Cartwright, May 1998 John H. Foster, Jean L. Hennessey, Sharon Wolchik Daniel L. Lamaute, (The George Washington Doris O. Mausui, University) Thomas R. Reedy, Nancy M. Zirkin COLD WAR INTERNATIONAL HISTORY PROJECT THE COLD WAR INTERNATIONAL HISTORY PROJECT WORKING PAPER SERIES CHRISTIAN F. OSTERMANN, Series Editor This paper is one of a series of Working Papers published by the Cold War International History Project of the Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars in Washington, D.C. Established in 1991 by a grant from the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation, the Cold War International History Project (CWIHP) disseminates new information and perspectives on the history of the Cold War as it emerges from previously inaccessible sources on “the other side” of the post-World War II superpower rivalry.