Frank Sargeson

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ascent03opt.Pdf

1.1.. :1... l...\0..!ll1¢. TJJILI. VOL 1 NO 3 THE CAXTON PRESS APRIL 1909 ONE DOLLAR FIFTY CENTS Ascent A JOURNAL OF THE ARTS IN NEW ZEALAND The Caxton Press CHRISTCHURCH NEW ZEALAND EDITED BY LEO BENSEM.AN.N AND BARBARA BROOKE 3 w-r‘ 1 Published and printed by the Caxton Press 113 Victoria Street Christchurch New Zealand : April 1969 Ascent. G O N T E N TS PAUL BEADLE: SCULPTOR Gil Docking LOVE PLUS ZEROINO LIMIT Mark Young 15 AFTER THE GALLERY Mark Young 21- THE GROUP SHOW, 1968 THE PERFORMING ARTS IN NEW ZEALAND: AN EXPLOSIVE KIND OF FASHION Mervyn Cull GOVERNMENT AND THE ARTS: THE NEXT TEN YEARS AND BEYOND Fred Turnovsky 34 MUSIC AND THE FUTURE P. Plat: 42 OLIVIA SPENCER BOWER 47 JOHN PANTING 56 MULTIPLE PRINTS RITA ANGUS 61 REVIEWS THE AUCKLAND SCENE Gordon H. Brown THE WELLINGTON SCENE Robyn Ormerod THE CHRISTCHURCH SCENE Peter Young G. T. Mofi'itt THE DUNEDIN SCENE M. G. Hire-hinge NEW ZEALAND ART Charles Breech AUGUSTUS EARLE IN NEW ZEALAND Don and Judith Binney REESE-“£32 REPRODUCTIONS Paul Beadle, 5-14: Ralph Hotere, 15-21: Ian Hutson, 22, 29: W. A. Sutton, 23: G. T. Mofiifi. 23, 29: John Coley, 24: Patrick Hanly, 25, 60: R. Gopas, 26: Richard Killeen, 26: Tom Taylor, 27: Ria Bancroft, 27: Quentin MacFarlane, 28: Olivia Spencer Bower, 29, 46-55: John Panting, 56: Robert Ellis, 57: Don Binney, 58: Gordon Walters, 59: Rita Angus, 61-63: Leo Narby, 65: Graham Brett, 66: John Ritchie, 68: David Armitage. 69: Michael Smither, 70: Robert Ellis, 71: Colin MoCahon, 72: Bronwyn Taylor, 77.: Derek Mitchell, 78: Rodney Newton-Broad, ‘78: Colin Loose, ‘79: Juliet Peter, 81: Ann Verdoourt, 81: James Greig, 82: Martin Beck, 82. -

Studio New Zealand Edition April 1948

i STUDIO-. , AND QUEENS- Founded in 1893 Vol 135 No &,I FROM HENRY VIII TO April 1948 -'- - RECENT IMPORTANT ' ARTICLES .. PAUL NASH 1889-1946 . Foreword by the Rt. Hon. ~gterFraser, C.H., P.C., M.P., (March) # ' - Prime Minister of New Zealand page IOI THE HERITAGE OF ART W INDl+, Contemporary Art in New Zealand by Roland Hipkins page Ioa by John Irwin I. 11 AND m New Zealand War Artists page 121 .. (~ecember,]anuary and February) - - Maori Art by W. J. Phillipps page 123 ' '-- I, JAMBS BAT- AU Architecture in New Zealand by Cedric Firth page 126 Book Production in New zealand page 130 - I, CITY OF BIRMINGW~~ ART GALLB&Y nb I by Trenchard Cox ..-- COLOUR PLA,"S . [Dctober) -7- SWSCVLPTwRB IN TEE HOME - WAXMANGUby Alice F. Whyte page 102 -- 1, -L by Kmeth Romney Towndrow -7 - STILL LIFE by T. A. McCormack page 103 (&ptember) ODE TO AUTUMN by A. Lois White page 106 NORWCH CASTLE MUSgUM -. AND ART GALLERY - PORTRAIT OF ARTIST'S WEB by M. T. Woollaston page 107 V. - by G. Barnard , ABSTRACT-SOFT'STONE WkTH WORN SHELL AND WOOD - L (August) - - by Eric Lee Johnson page I 17 1 -*, 8 I20 ~wyrightin works rernohcd in - HGURB COMPOSITION by Johtl Weeks page TH~snn,ro is stridty rewed ' 'L PATROL, VBUA LAVBLLA, I OCTOBER, 1943, by J. Bowkett Coe page 121 . m EDITOR is always glad to consfder proposals for SVBSCBIPTION Bdm (post free) 30s. Bound volume d be s&t to ,SmIO in edftorial contrlbutlons, but a letter out&& the (six issues) 17s 61 Caaads. -

Canterbury 1944

CANTERBURY SOCIETY OF ARTS CATALOGUE OF THE SIXTY-FOURTH ANNUAL EXHIBITION 1944 Held at DUNSTABLE HOUSE By courtesy of J. BALLANTYNE & CO. LTD. Cashel & Colombo Streets. Christchurch. N.Z. CANTERBURY SOCIETY OF ARTS SIXTY- FOURTH -Qnnu.a.1 tlx-kilyitlon Opened by the President, Mr. Archibald F. Nicoll ON TUESDAY, MARCH 14th, 1944 Patron: HIS EXCELLENCY THE GOVERNOR-GENERAL, SIR CYRIL NEWALL, G.C.B., O.M., G.C.M.G., C.B.E:, A.M. President: ARCHIBALD F. NICOLL Vice-Presidents: H. G. HELMORE Dr. G. M. L. LESTER C. F. KELLY SYDNEY L. THOMPSON, O.B.E. W. T. TRETHEWEY Council: OLIVIA SPENCER BOWER C. S. LOVELL-SMITH A. E. FLOWER GEOFFREY WOOD A. ELIZABETH KELLY, C.B.E. A. C. BRASSINGTON W. S. NEWBURGH Hon. Treasurer: . R. WALL WORK, A.R.C.A. (London) Secretary: W. S. BAVERSTOCK Hon. Auditor: H. BICKNELL, F.P.A.N.Z., F.I.A.N.Z., F.C.I.S. Exhibition will open daily from 9 a.m. to 5.30 p.m. and on Friday Nights. Page Three LIFE MEMBERS Heywood, Miss Rhodes, Sir R. Hea-ton Thomas, Mrs. R. D. Irving, Dr. W. Spencer, Mrs. A. C. D. Wright, F. E. Peacock, W. M. H. McRae ORDINARY MEMBERS Acland, Sir Hugh Caddick, A. E. Gibbs, Miss M. Men- Alcock, Mrs. J. A. M. Callender, Geo. zies Adams, Mrs. E. A. Carey, W. R. Gibbs, T. N. Aitken, Dr. W. Catherwood, Mrs. James Gibbs, Miss C. M. Aitken, Mrs. G. G. Clark, Chas. R. Godby, Mrs. M. H. Godfrey, S. -

Community Services Committee Agenda 6 November 2000

ROBERT MCDOUGALL ART GALLERY AND ART ANNEX REPORT ON ACTIVITIES FOR THE FINANCIAL YEAR 1 JULY 1999 - 30 JUNE 2000 PREPARED BY: ART GALLERY DIRECTOR AND ART GALLERY STAFF TABLE OF CONTENTS PAGE NO. BUSINESS UNIT SUMMARY REPORT ART COLLECTION REPORT EXHIBITIONS REPORT INFORMATION & ADVICE REPORT ACQUISITION APPENDIX PAGE NO. 3 6 8 15 18 BUSINESS UNIT ART GALLERY FINANCIAL RESULTS FOR TWELVE MONTHS TO 30 JUNE 2000 Financial Performance Last Year Current Year Corporate Plan Reference Page 8.3.1 Actual Budget Actual Expenditure Art Collection $778,121 $755,678 $718,190 Exhibitions $1,218,120 $1,274,813 $1,131,178 Information & Advice $559,780 $659,545 $717,276 $2,556,021 $2,690,036 $2,566,644 Revenue Art Collection -$81,383 -$58,725 -$52,127 Exhibitions -$325,346 -$317,000 -$185,530 Information & Advice -$38,781 -$202,000 -$143,773 -$445,510 -$577,725 -$381,430 Net Cost of Art Gallery Operations $2,110,511 $2,112,311 $2,185,214 Capital Outputs Renewals & Replacements $28,764 $31,800 $35,753 Asset Improvements $0 $0 $0 New Assets $365,764 $179,887 $170,082 Sale of Assets -$22 $0 $0 Net Cost of Art Gallery Capital Programme $394,506 $211,687 $205,835 Objective To enhance the cultural well-being of the community through the cost effective provision and development of a public art museum, to maximise enjoyment of visual art exhibitions, and to promote public appreciation of Canterbury art, and more widely, the national cultural heritage by collecting, conserving, researching and disseminating knowledge about art. -

Annual Exhibition of New Zealand Art

CATALOGUE CANTERBURY SOCIETY OF ARTS INCORPORATED SEVENTY-FIFTH Annual Exhibition of New Zealand Art 1955 ART GALLERY DURHAM STREET CHRISTCHURCH v CANTERBURY SOCIETY OF ARTS (Incorporated) SEVENTY-FIFTH Annual Exhibition Opened by the President C. S. LOVELL-SMITH, Esq. on THURSDAY, MARCH 31st, 1955 PATRON HIS EXCELLENCY THE GOVERNOR-GENERAL, LIEUT.-GENERAL SIR WILLOUGHBY CHARLES NORRIE, G.C.V.O., G.C.M.G., C.B., D.S.O., M.C. PRESIDENT C. S. LOVELL-SMITH, F.R.S.A., D.F.A. (N.Z.) VICE-PRESIDENTS H. G. HELMORE, M.B.E. SYDNEY L. THOMPSON, O.B.E. GEOFFREY WOOD W. T. TRETHEWEY RUSSELL CLARK COUNCIL RONA FLEMING G. C. C. SANDSTON, M.B.E., LL.M. IVY G. FIFE, D.F.A. (N.Z.) ERIC J. DOUDNEY, F.R.B.S. A. A. G. REED, LL.B. STEWART W. MINSON, A.R.I.B.A. W. A. SUTTON, D.F.A. (N.Z.) DOROTHY MANNING HON. TREASURER R. WALLWORK, A.R.C.A. (LONDON) SECRETARY-TREASURER W. S. BAVERSTOCK, F.R.S.A. HON. AUDITOR H. BICKNELL, F.P.A.N.Z., F.I.A.N.Z., F.C.I.S. (ENG.) HON. SOLICITORS Messrs. WILDING, PERRY & ACLAND EXHIBITION HOURS Mondays to Saturdays.—10 a.m. to 5 p.m. Sundays.—2 to 4.30 p.m. Evening Hours.—Mondays, Wednesdays and Fridays, 7.30 to 9.30 p.m. Tickets for PUBLIC ART UNION (drawn during Exhibition) obtainable at Desk. NOTE The Secretary will be available during the whole period of the Exhibition. He will enrol new members for our increased activities, receive subscriptions and answer enquiries regarding the purchase of pictures. -

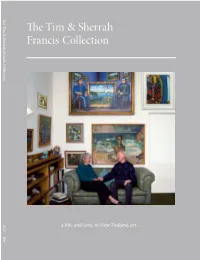

The Tim & Sherrah Francis Collection

The Tim & Sherrah FrancisTimSherrah & Collection The The Tim & Sherrah Francis Collection A+O 106 a life, and love, in New Zealand art… The Tim & Sherrah Francis Collection Art + Object 7–8 September 2016 Tim and Sherrah Francis, Washington D.C., 1990. Contents 4 Our Friends, Tim and Sherrah Jim Barr & Mary Barr 10 The Tim and Sherrah Francis Collection: A Love Story… Ben Plumbly 14 Public Programme 15 Auction Venue, Viewing and Sale details Evening One 34 Yvonne Todd: Ben Plumbly 38 Michael Illingworth: Ben Plumbly 44 Shane Cotton: Kriselle Baker 47 Tim Francis on Shane Cotton 53 Gordon Walters: Michael Dunn 64 Tim Francis on Rita Angus 67 Rita Angus: Vicki Robson 72 Colin McCahon: Michael Dunn 75 Colin McCahon: Laurence Simmons 79 Tim Francis on The Canoe Tainui 80 Colin McCahon, The Canoe Tainui: Peter Simpson 98 Bill Hammond: Peter James Smith 105 Toss Woollaston: Peter Simpson 108 Richard Killeen: Laurence Simmons 113 Milan Mrkusich: Laurence Simmons 121 Sherrah Francis on The Naïve Collection 124 Charles Tole: Gregory O’Brien 135 Tim Francis on Toss Woollaston Evening Two 140 Art 162 Sherrah Francis on The Ceramics Collection 163 New Zealand Pottery 168 International Ceramics 170 Asian Ceramics 174 Books 188 Conditions of Sale 189 Absentee Bid Form 190 Artist Index All quotes, essays and photographs are from the Francis family archive. This includes interviews and notes generously prepared by Jim Barr and Mary Barr. Our Friends, Jim Barr and Mary Barr Tim and Sherrah Tim and Sherrah in their Wellington home with Kate Newby’s Loads of Difficult. -

New Zealand Potter Volume 12 Number 1 Autumn 1970

NEW ZEALAND I I NEW ZEALAN contents VOLUME 12/1 AUTUMN 1970 13th exhibition 2 The :: _ potter 7 About the guest artists 1 Potters symposium 1 1 3 :.__.-_.:.4. Entrainment 16 Domestic ware: scope for discipline and imagination 20 Ceramic murals ,_._—. 23 Hall of Asian art 28 A or P? A question of status 34 Newcomers _ . 39 editorial . After the 13th 46 News of people, pots and events 53 12 Year Itch! English studio pottery today it will be obvious from articles in this issue of the Potter that some conflicting opinions are held as to how the potter's association should NEW ZEALAND POTTER is a non-profit-making be shaped to meet the needs of all New Zealand potters. twice annually in Autumn and magazine published There will be some changes. This year no annual exhibition will be Spring. held. The New Zealand Society of Potters will be considering other rates: Subscription ways of admitting new members and other ways of showing Zealand: $2 per annum, post free. Within New their work. Australia: $2.20 Canada, U.S.A.: $U82.4O United Kingdom: 22/- A. strong plea is heard for a change of emphasis within the Other countries: $US 2.40 Socrety to lay greater stress on the work of 'professional potters'. Some potters even want a separate association to promote their interests: In this issue some of these people express their views. Harris Editor Margaret By examining their requirements of a potter’s association it will be Lay-out and Juliet Peter clear what they object to in the present Society. -

B.150 Bulletin of Christchurch Art Gallery Te Puna O Waiwhetu

BULLETIN OF CHRISTCHURCH ART GALLERY TE PUNA O WAIWHETU spring september – november 2007 Exhibitions Programme b.150 September, October, November Bulletin Editor: Sarah Pepperle 2 Foreword Gallery Contributors A few words from the Director Director: Jenny Harper JULIAN DASHPER: TO THE UNKNOWN NEW ZEALANDER Curator: Peter Vangioni An exhibition by one of New Zealand’s leading Burdon Family Gallery, Balcony Assistant Curator: Ken Hall 3 My Favourite contemporary artists. & Collection Galleries Public Programmes Officer: Ann Betts Christopher Moore makes his choice • until 14 October Gallery Photographer: Brendan Lee • publication available PHIL DADSON: AERIAL FARM Friends of Christchurch Art Gallery: Cheryl Comfort, Paul Deans 4 Noteworthy Video and audio material recorded in the Dry Valleys of Tait Electronics Other Contributors News bites from around the Gallery Antarctica explore an environment through sound and image. Antarctica Gallery Andrew Clifford, Julian Dashper, Christopher Moore, Bruce Russell • until 14 October BILL HAMMOND: JINGLE JANGLE MORNING Tel (+64-3) 941 7300 Fax (+64-3) 941 7301 8 The Year in Review The long-awaited spectacular survey exhibition of more than Email [email protected] [email protected] Touring Exhibition Galleries Please see the back cover for more details. A summary of business, 1 July 2006 – 30 June 2007 two decades of work by one of New Zealand’s most sought-after & Borg Henry Gallery contemporary painters. • until 22 October We welcome your feedback and suggestions for future articles. Principal Exhibition Sponsor: Ernst & Young. The exhibition and accompanying • publication available 10 To the Unknown New Zealander publication are supported by the Friends of Christchurch Art Gallery, Creative New Peter Vangioni interviews Julian Dashper Zealand and Spectrum Print. -

A.R.D. Fairburn Juliet Peter Robert Ellis Roy Eeks Don Driver Roy Cowan

JOSE BRIBIESCA DON RAMAGE A.R.D. FAIRBURN JULIET PETER ROBERT ELLIS ROY GOOD EILEEN MAYO JOHN WEEKS DON DRIVER ROY COWAN GARTH CHESTER BOB ROUKEMA JOHN CRICHTON LEN CASTLE MODERNISM IN RUSSELL CLARK MERVYN WILLIAMS COLIN McCAHON TED DUTCH NEW ZEALAND ANDRE BROOKE FRANK HOFMANN FREDA SIMMONDS GREER TWISS THEO SCHOON ROSS RITCHIE GEOFFREY FAIRBURN FRANK CARPAY RUTH CASTLE JOVA RANCICH JOHN MID- DLEDITCH ELIZABETH MATHESON MIREK SMISEK RICHARD PARKER JEFF SCHOLES ANNEKE BORREN ROBYN STEWART PETER STICHBURY MILAN MRKUSICH BARRY BRICKELL JEAN NGAN VIVIENNE MOUNTFORT GEORGIA SUITER THEO JANSEN DA- VID TRUBRIDGE CES RENWICK EDGAR MANSFIELD PETER SAUERBIER STEVE RUM- SEY DOROTHY THORPE LEVI BORGSTROM SIMON ENGELHARD TONY FOMISON PAUL MASEYK RICK RUDD DOREEN BLUMHARDT A RT+O BJ EC T LEO KING PATRI- CIA PERRIN DAVID BROKENSHIRE MANOS NATHAN 21 MAY 2014 WI TAEPA MURIEL MOODY WARREN TIPPETT ELIZABETH LISSAMAN BUCK NIN E.MERVYN TAYLOR AO722FA Cat78 cover.indd 1 5/05/14 1:34 PM AO722FA Cat78 cover.indd 2 5/05/14 1:34 PM Modernism in New Zealand Wednesday, 21 May 2014 6.30pm AO722FA Cat78 text p-1-24.indd 1 6/05/14 1:02 PM Inside front cover: Inside back cover: Frank Hofmann, A.R.D. Fairburn, Composition with Study of Maori Rock Cactus, 1952 (detail), Drawings (detail), Be uick. vintage gelatin silver vintage screenprinted print. Lot 274. fabric mounted to “Strictly speaking New Zealand doesn’t board. Lot 251. Looking for a Q? At these extraordinary prices you’ll have to hurry. exist yet, though some possible New Zealands glimmer in some poems and in some canvases. -

COLIN Mccahon, HIGH ART, and the COMMON CULTURE 1947-2000

1 ‘THE AWFUL STUFF’: COLIN McCAHON, HIGH ART, AND THE COMMON CULTURE 1947-2000 Lara Strongman A thesis submitted to the Victoria University of Wellington In fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Victoria University of Wellington 2013 2 Why this sudden uneasiness and confusion? (How serious the faces have become.) Why are the streets and squares emptying so quickly, As everyone turns homeward, deep in thought? Because it is night, and the barbarians have not arrived. And some people have come from the borders saying that there are no longer any barbarians. And now what will become of us, without any barbarians? After all, those people were a solution. — Constantin Cavafy, from ‘Waiting for the Barbarians’, 1904 3 CONTENTS ABSTRACT ............................................................................................................................... 5 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ....................................................................................................... 7 LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS ................................................................................................... 11 INTRODUCTION: HIGH ART AND THE COMMON CULTURE ..................................... 14 A note on terms .................................................................................................................... 27 PART ONE: COLIN MCCAHON 1947-1950: ‘SEEKING CULTURE IN THE WRONG PLACES’ ................................................................................................................................ -

ANNUAL EXHIBITION of NEW ZEALAND ART

CANTERBURY SOCIETY OF ARTS (INCORPORATED) CATALOGUE of the SEVENTY-FOURTH ANNUAL EXHIBITION of NEW ZEALAND ART 1954 ART GALLERY DURHAM STREET :: CHRISTCHURCH CANTERBURY SOCIETY OF ARTS (Incorporated) •* SEVENTY-FOURTH ANNUAL EXHIBITION Opened by the President, C. S. LOVELL-SMITH, Esq., on WEDNESDAY, APRIL 21st, 1954 % Patron: HIS EXCELLENCY THE GOVERNOR-GENERAL, LIEUT.-GENERAL SIR WILLOUGHBY CHARLES NORRIE, G.C.V.O., G.C.M.G., C.B., D.S.O., M.C. President: C. S. LOVELL-SMITH, F.R.S.A., D.F.A. (N.Z.) Vice-Presidents: H. G. HELMORE, M.B.E. SYDNEY L. THOMPSON, O.B.E. GEOFFREY WOOD W. T. TRETHEWEY RUSSELL CLARK Council: RONA FLEMING G. C. C. SANDSTON, M.B.E., LL.M. IVY G. FIFE, D.F.A. (N.Z.) ERIC J. DOUDNEY, F.R.B.S., F.R.S.A. A A. G. REED, LL.B. STEWART W. MINSON, A.R.I.B.A. W. A. SUTTON, D.F.A. (N.Z.) DOROTHY MANNING Hon. Treasurer: R. WALLWORK, A.R.C.A. (London) Secretary-Treasurer: W. S. BAVERSTOCK, F.R.S.A. Hon. Auditor: H. BICKNELL, F.P.A.N.Z., F.I.A.N.Z., F.C.I.S. (Eng.) Hon. Solicitors: Messrs WILDING, PERRY k ACLAND EXHIBITION HOURS: Mondays to Saturdays.—10 a.m. to 5 p.m. Sundays.—2 to 4.30 p.m. Evening Hours.—Mondays, Wednesdays and Fridays, 7.30 to 9.30 p.m. Tickets for PUBLIC ART UNION {drawn during Exhibition) obtainable at Desk. NOTE The Secretary will be available during the whole period of the Exhibition. -

Community Services Committee Agenda 9 October 2000

52%(57Ã0&'28*$//Ã$57Ã*$//(5< $1'Ã$57Ã$11(; 5(3257Ã21Ã$&7,9,7,(6Ã )25Ã7+(Ã),1$1&,$/Ã<($5 Ã-8/<ÃÃÃÃ-81(Ã 35(3$5('Ã%< $57Ã*$//(5<Ã',5(&725 $1'Ã$57Ã*$//(5<Ã67$)) 7$%/(Ã2)Ã&217(176 3 %86,1(66Ã81,7Ã6800$5<Ã5(3257 $57Ã&2//(&7,21Ã5(3257 (;+,%,7,216Ã5(3257 ,1)250$7,21ÃÉÃ$'9,&(Ã5(3257 $&48,6,7,21Ã$33(1',; 3$*(Ã12 %86,1(6681,7 $57*$//(5< ),1$1&,$/5(68/76 )257:(/9(0217+672-81( )LQDQFLDO3HUIRUPDQFH /DVW<HDU &XUUHQW<HDU &RUSRUDWH3ODQ5HIHUHQFH3DJH $FWXDO %XGJHW $FWXDO ([SHQGLWXUH $UW &ROOHFWLRQ ([KLELWLRQV ,QIRUPDWLRQ $ $GYLFH 5HYHQXH $UW &ROOHFWLRQ ([KLELWLRQV ,QIRUPDWLRQ $ $GYLFH 1HW &RVW RI $UW *DOOHU\ 2SHUDWLRQV &DSLWDO 2XWSXWV 5HQHZDOV $ 5HSODFHPHQWV $VVHW ,PSURYHPHQWV 1HZ $VVHWV 6DOH RI $VVHWV 1HW &RVW RI $UW *DOOHU\ &DSLWDO 3URJUDPPH 2EMHFWLYH 7R HQKDQFH WKH FXOWXUDO ZHOOEHLQJ RI WKH FRPPXQLW\ WKURXJK WKH FRVW HIIHFWLYH SURYLVLRQ DQG GHYHORSPHQW RI D SXEOLF DUW PXVHXP WR PD[LPLVH HQMR\PHQW RI YLVXDO DUW H[KLELWLRQV DQG WR SURPRWH SXEOLF DSSUHFLDWLRQ RI &DQWHUEXU\ DUW DQG PRUH ZLGHO\ WKH QDWLRQDO FXOWXUDO KHULWDJH E\ FROOHFWLQJ FRQVHUYLQJ UHVHDUFKLQJ DQG GLVVHPLQDWLQJ NQRZOHGJH DERXW DUW 2SHUDWLRQDO&RPSRQHQWV ,QWURGXFWLRQRI6$35HSRUWLQJV\VWHP 'XULQJ WKH ILQDQFLDO \HDU WKH 6$3 UHSRUWLQJ V\VWHP ZDV LQWURGXFHG 7KLV XVHV GLIIHUHQW PHWKRGRORJ\ LQ DOORFDWLQJ FRVWV SDUWLFXODUO\ LQ WKH RYHUKHDG DOORFDWLRQ DUHD 7KLV KDV WHQGHG WR GLVWRUW WKH LQGLYLGXDO RXWSXW ILQDQFLDO UHVXOWV E\ UHGLVWULEXWLQJ FRVWV SUHYLRXVO\ EXGJHWHG XQGHU RWKHU RXWSXWV )RU WKH SXUSRVH RI UHWDLQLQJ VRPH FODULW\ LQ ILQDQFLDO DQDO\VLV D VXPPDU\