Radomír D. Kokeš Masaryk University

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mattel Films and Blumhouse Productions Partner to Bring ‘Magic 8 Ball®’ to the Big Screen

Mattel Films and Blumhouse Productions Partner to Bring ‘Magic 8 Ball®’ to the Big Screen June 3, 2019 First collaboration between Mattel Films and Blumhouse Productions, the producer of Get Out, Ma, Halloween Film director Jeff Wadlow, whose work includes Kick-Ass 2, Truth or Dare and the upcomingFantasy Island, has signed on to direct the production Sixth live-action film project Mattel Films has in development since its creation nine months ago, including Barbie®, Hot Wheels®, Masters of the Universe®, American Girl® and View Master® EL SEGUNDO, Calif.--(BUSINESS WIRE)--Jun. 3, 2019-- Mattel, Inc. (NASDAQ: MAT) today announced a partnership with Academy Award®- nominated production company Blumhouse Productions to create a live-action feature film based on the iconic, fortune-telling Magic 8 Ball®, selected by Time magazineas one of the100 greatest toys of all time. The film will be directed by critically-acclaimed director Jeff Wadlow, whose previous work includes notable films such as Kick-Ass 2 and Truth or Dare. Wadlow is writing the script with his collaborators, Jillian Jacobs and Chris Roach. This marks Mattel Film’s first partnership with independent powerhouse Blumhouse Productions, whose films have grossed more than $3 billion at the worldwide box office. The suspense-filled Magic 8 Ball movie will be adapted for audiences worldwide. It also marks the sixth project Mattel Films has in development, including plans to create feature films based on Mattel’s Barbie®, Hot Wheels®, Masters of the Universe®, American Girl® and View Master® brands. “Since the 1950s, Magic 8 Ball has inspired imagination, suspense and intrigue across generations. -

Bike Sharing Pedals Into Jacksonville

Jacksonville, AL JSU’s Student-Published Newspaper Since 1934 January 24, 2019 in ARTS & ENTERTAINMENT 2019 Oscar Nominations released Page 5 in NEWS Daniel Mayes/The Chanticleer VeoRide Fleet Coordinator Trent Dickeson, a graduate of JSU, shows off the new bikes that Jacksonville residents and JSU students will be able to use. COMMUNITY Shutdown enters fifth week Bike sharing pedals Page 2 into Jacksonville VeoRide, which is the first company of its Daniel Mayes in SPORTS Editor-in-Chief kind to come to Alabama, allows users to use a bike by downloading an app, scanning Have you ever faced the dreaded walk to a QR code on the bike, and then taking off. or from Stone Center and wished there was a Users are charged 50 cents per 15 minutes on way to move more quickly? Wanted to finally the bike, and monthly and yearly packages get out and explore more of the Ladiga Trail? are also available for repeat users. Wanted to bring your bike to campus, but The company launched their program, don’t want to deal with storage, upkeep, or which will start in Anniston, Oxford and the risk of getting it stolen? Jacksonville, with an event at the Jacksonville A new bike-sharing company coming to Train Depot on Friday, where the public and Gamecocks duo receives town might just be for you. OVC, national honors see BIKE page 2 Page 8 COMMUNITY on CAMPUS Local man campaigns to bring TV series to Jacksonville International JP Wood House Staff Reporter Presentation: It could be out with the Benin construction equipment and Thursday, in with the camera equipment January 24, soon in Jacksonville. -

Spring 2021 Spring 2021

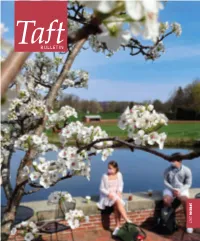

SPRING 2021 SPRING 2021 INSIDE 42 Unscripted: How filmmakers Peter Berg ’80 and Jason Blum ’87 evolved during a year of COVID-19 By Neil Vigdor ’95 c 56 Confronting the Pandemic Dr. Paul Ehrlich ’62 and his work as a New York City allergist-immunologist By Bonnie Blackburn-Penhollow ’84 b OTHER DEPARTMENTS 3 On Main Hall 5 Social Scene 6 Belonging 24/7 Elena Echavarria ’21 8 Alumni Spotlight works on a project in 20 In Print Advanced Ceramics 26 Around the Pond class, where students 62 do hands-on learning Class Notes in the ceramics studio 103 Milestones with teacher Claudia 108 Looking Back Black. ROBERT FALCETTI 8 On MAIN HALL A WORD FROM HEAD Managing Stress in Trying Times OF SCHOOL WILLY MACMULLEN ’78 This is a column about a talk I gave and a talk I heard—and about how SPRING 2021 ON THE COVER schools need to help students in managing stress. Needless to say, this Volume 91, Number 2 Students enjoyed the warm spring year has provided ample reason for this to be a singularly important weather and the beautiful flowering EDITOR trees on the Jig Patio following focus for schools. Linda Hedman Beyus Community Time. ROBERT FALCETTI In September 2018, during my opening remarks to the faculty, I spoke about student stress, and how I thought we needed to think about DIRECTOR OF MARKETING AND COMMUNICATIONS Kaitlin Thomas Orfitelli it in new ways. I gave that talk because it was clear to me that adolescents today were ASSISTANT DIRECTOR OF MARKETING AND COMMUNICATIONS experiencing stress and managing stress in different ways than when I Debra Meyers began teaching and even when I began as head of school just 20 years PHOTOGRAPHY ago. -

Volunteers Sought for New Youth Running Series

TONIGHT Clear. Low of 13. Search for The Westfield News The WestfieldNews Search for The Westfield News “I DO NOT Westfield350.com The WestfieldNews Serving Westfield, Southwick, and surrounding Hilltowns “TIME ISUNDERSTAND THE ONLY WEATHER CRITIC THEWITHOUT WORLD , TONIGHT AMBITIONBUT I WATCH.” Partly Cloudy. ITSJOHN PROGRESS STEINBECK .” Low of 55. www.thewestfieldnews.com Search for The Westfield News Westfield350.comWestfield350.org The WestfieldNews — KaTHERINE ANNE PORTER “TIME IS THE ONLY VOL. 86 NO. 151 Serving Westfield,TUESDAY, Southwick, JUNE 27, and2017 surrounding Hilltowns 75 cents VOL.88WEATHER NO. 53 MONDAY, MARCH 4, 2019 CRITIC75 CentsWITHOUT TONIGHT AMBITION.” Partly Cloudy. JOHN STEINBECK Low of 55. www.thewestfieldnews.com Attention Westfield: Open Space VOL. 86 NO. 151 75 cents Let’s ‘Retire the Fire!’ CommitteeTUESDAY, JUNE 27, 2017 By TINA GORMAN discussing Executive Director Westfield Council On Aging With support from the changes at Westfield Fire Department, the Westfield Public Safety Communication Center, the next meeting Westfield News, the Westfield By GREG FITZPATRICK Rotary Club, and Mayor Brian Correspondent Sullivan, the Westfield Council SOUTHWICK – The Open On Aging is once again launch- Space Committee is holding ing its annual Retire the Fire! another meeting on Wednesday at fire prevention and safety cam- 7 p.m. at the Southwick Town paign for the City’s older Hall. TINA GORMAN According to Open Space adults. During the week of Executive Director March 4 to 8, residents of Committee Chairman Dennis Westfield Council Clark, the meeting will consist of Westfield will see Retire the On Aging Fire! flyers hung throughout reviewing at the changes that have the City and buttons with the been made to the plan, including Sunny Sunday Skier at Stanley Park slogan worn by Council On Aging staff, seniors, and the new mapping that will be Kim Saffer of Westfield gets in some cross-country ski practice on a sunny community leaders. -

TOBY OLIVER, ACS Director of Photography Tobyoliver.Com

TOBY OLIVER, ACS Director of Photography tobyoliver.com PROJECTS Partial List DIRECTORS STUDIOS/PRODUCERS DAY SHIFT J.J. Perry 87ELEVEN / NETFLIX Feature Film Shaun Redick, Yvette Yates Redick Jamie Foxx, Chad Stahelski SERIOUSLY RED Gracie Otto DOLLHOUSE PICTURES Feature Film ROADSHOW FILMS Lois Randall, Jessica Carrera Robyn Kershaw DEAD TO ME Silver Tree CBS TV / NETFLIX Season 2 Jennifer Getzinger Joe Hardesty, Liz Feldman Elizabeth Allen Rosenbaum BARB & STAR GO TO VISTA DEL MAR Josh Greenbaum GLORIA SANCHEZ PROD / LIONSGATE Feature Film Jonathan McCoy, Jessica Elbaum Margot Hand, Andrea Gamboa Adam McKay, Annie Mumolo FANTASY ISLAND Jeff Wadlow BLUMHOUSE / SONY PICTURES Feature Film Robin Fisichella, Jason Blum Marc Toberoff THE DIRT Jeff Tremaine NETFLIX Feature Film Allen Kovac, Erik Olsen, Julie Yorn GET OUT Jordan Peele BLUMHOUSE / UNIVERSAL PICTURES Feature Film Marcei Brown, Jordan Peele Winner - Oscar Best Original Screenplay Jason Blum, Shaun Redick 4 Academy Award Nominations Edward H. Hamm Jr., Gerard DiNardi HAPPY DEATH DAY 2 U Christopher Landon BLUMHOUSE / UNIVERSAL PICTURES Feature Film Samson Mucke, Jason Blum Scott Lobdell WILDLING Fritz Bohm MAVEN PICTURES / IM GLOBAL Feature Film Marco Henry, Celine Rattray, Trudie Official Selection – SXSW Styler, Liv Tyler, Charlotte Ubben BREAKING IN James McTiegue UNIVERSAL PICTURES Feature Film Valerie Sharp, Will Packer HAPPY DEATH DAY Christopher Landon BLUMHOUSE / UNIVERSAL PICTURES Feature Film Seth William Meier, John Baldecchi Jason Blum, Angela Mancuso INSIDIOUS: THE LAST KEY Adam Robitel BLUMHOUSE / COLUMBIA PICTURES Feature Film Rick Osako, Jason Blum, Oren Peli James Wan, Leigh Whannell INNOVATIVE-PRODUCTION.COM | 310.656.5151 . -

Ironwood Football Stadium Renamed After Late Football Coach, Mr. Esquivel

The Ironwood High School Glendale, Arizona Eagle’s Eye Volume 32 Issue 2 October 13, 2017 What’s inside? News Read about how minimum wage is affecting teens getting jobs on... Page 2 Feature Did you tune into Ironwood’s Homecoming? Sarah Saunders Furthermore, Ironwood’s clubs ber said, “It’s a lot of fun, but sought after Homecoming crowns Staff Reporter were tasked with representing kind of stressful putting it all to- were awarded to the deserving Crowns. Carnivals. Football. themselves in a creative way to gether.” Their work did not go un- Homecoming king and queen. It That is right, once again Home- show on display for appreciated. Each club and sport was now that the long awaited for Know what the recent fall play is coming has occurred and the an- As stated by Ironwood.com, was represented given credit. Homecoming dance would com- about on... nual event did not disappoint the Wednesday brought each club The festivities and must-do ac- mence the next night. Page 4 community and high-school stu- together for the Homecoming pa- tivities did not end in the morn- It was Saturday morning that dents of Ironwood. rade from 2:00 PM to 2:20 PM. ing. Once the sun went down, the Eagles Eye fulfilled their an- Entertainment From October The floats were a success, and Ironwood came to life on nual task of decorating second to Octo- thankfully not many incidents the football field. Students, for the Homecom- ber seventh, ensued. staff, and parents all came ing dance. the week However, Thursday was to the Varsity football game Their efforts was filled jampacked with prepara- to cheer on the Eagles. -

Bear Mccreary

BEAR MCCREARY COMPOSER AWARDS INTERNATIONAL FILM MUSIC CRITICS ASSOCIATON AWARD 2019 Film Composer of the Year ASCAP COMPOSER’S CHOICE AWARD 2016 TV Composer of the Year PRIMETIME EMMY AWARD NOMINATION OUTLANDER (2015) Outstanding Music Composition for a Series ASCAP COMPOSER’S CHOICE AWARD 2014 TV Composer of the Year PRIMETIME EMMY AWARD NOMINATION BLACK SAILS (2014) Outstanding Original Main Title Theme Music PRIMETIME EMMY AWARD WINNER DA VINCI’S DEMONS (2013) Outstanding Original Main Title Theme Music PRIMETIME EMMY AWARD NOMINATION HUMAN TARGET (2010) Outstanding Original Main Title Theme Music MOTION PICTURES FREAKY Christopher Landon, dir. Blumhouse Productions AVA Tate Taylor, dir. Vertical Entertainment THE BABYSITTER: KILLER QUEEN McG, dir. Netflix FANTASY ISLAND Jeff Wadlow, dir. Sony 3349 Cahuenga Boulevard West, Los Angeles, California 90068 Tel. 818-380-1918 Fax 818-380-2609 McCreary Page 1 of 5 BEAR MCCREARY COMPOSER MOTION PICTURES (cont’d) CRIP CAMP James Lebrecht, Nicole Newnham, dirs. Higher Ground Productions THE SHED (score produced by) Frank Sabatella, dir. A Bigger Boat ELI Ciaran Foy, dir. Netflix CHILD’S PLAY Lars Klevberg, dir. United Artists GODZILLA: KING OF THE MONSTERS Michael Dougherty, dir. Warner Bros. RIM OF THE WORLD McG, dir. Netflix THE PROFESSOR AND THE MADMAN Farhad Safinia, dir. Icon Entertainment International HAPPY DEATH DAY 2U Christopher Landon, dir. Universal Pictures WELCOME HOME George Ratliff, dir. AMBI Group I STILL SEE YOU Scott Speer, dir. Golden Circle Films HELL FEST Gregory Plotkin, dir. CBS Films TAU Federico D’Alessandro, dir. Bloom THE CLOVERFIELD PARADOX Julius Onah, dir. Netflix ANIMAL CRACKERS Tony Bancroft, Scott Christian Sava, dir. -

Nancy Nayor Casting Resume May 2014 1

Nancy Nayor Casting Resume May 2014 1 NANCY NAYOR CASTING Office: 323-857-0151 / Cell: 213-309-8497 E-mail: [email protected] / Website: www.nancynayorcasting.com SENIOR VP OF FEATURE FILM CASTING, UNIVERSAL STUDIOS 1983-1997 HOME Director: Dennis Iliadis Producers: Universal, Appian Way, Blumhouse, GK Films Cast: Topher Grace, Patricia Clarkson, Callan Mulvey, Genesis Rodriguez THE MESSENGERS (CBS / CW PILOT) Director: Stephen Williams Producers: Thunder Road Pictures, Eoghan O’Donnell, Ava Jamshidi Cast: Diogo Morgado, Shantel VanSanten, Jon Fletcher, Sofia Black-D’Elia, Joel Courtney, JD Pardo OUIJA Director: Stiles White Producers: Universal, Platinum Dunes, Jason Blum, Hasbro Cast: Olivia Cooke, Douglas Smith, Daren Kagasoff, Bianca Santos, Shelley Hennig BOY NEXT DOOR Director: Rob Cohen Producers: Universal, Jason Blum, Elaine Goldsmith-Thomas, Benny Medina, John Jacobs Cast: Jennifer Lopez, Kristin Chenoweth, John Corbett, Hill Harper VISIONS Director: Kevin Greutert Producers: Universal, Blumhouse Cast: Isla Fisher, Anson Mount, Gillian Jacobs, Jim Parsons, Eva Longoria THE TOWN THAT DREADED SUNDOWN Director: Alfonso Gomez-Rejon Producers: MGM, Ryan Murphy, Jason Blum Cast: Addison Timlin, Gary Cole, Veronica Cartwright, Denis O’Hare, Anthony Anderson 21 AND OVER Directors: Scott Moore, Jon Lucas Producers: Relativity Media, Mandeville Films Cast: Miles Teller, Skylar Astin, Justin Chon, Sarah Wright BREAKPOINT Director: Jay Karas Producers: Gabriel Hammond, Lauren McCarthy Cast: Jeremy Sisto, Amy Smart, JK Simmons, -

UNIVERSAL PICTURES Presents a BLUMHOUSE/GOALPOST

UNIVERSAL PICTURES Presents A BLUMHOUSE/GOALPOST Production In Association with NERVOUS TICK PRODUCTIONS ELISABETH MOSS ALDIS HODGE STORM REID HARRIET DYER MICHAEL DORMAN and OLIVER JACKSON-COHEN Executive Producers LEIGH WHANNEL COUPER SAMUELSON BEATRIZ SEQUEIRA JEANETTE VOLTURNO ROSEMARY BLIGHT BEN GRANT Produced by JASON BLUM, p.g.a. KYLIE DU FRESNE, p.g.a. Screenplay and Screen Story by LEIGH WHANNELL Directed by LEIGH WHANNELL The Invisible Man_Production Information 2 PRODUCTION INFORMATION What you can’t see can hurt you. Emmy Award winner ELISABETH MOSS (Us, Hulu’s The Handmaid’s Tale) stars in a terrifying modern tale of obsession inspired by Universal’s classic Monster character. Trapped in a violent, controlling relationship with a wealthy and brilliant scientist, Cecilia Kass (Moss) escapes in the dead of night and disappears into hiding, aided by her sister Emily (HARRIET DYER, NBC’s The InBetween), their childhood friend James (ALDIS HODGE, Straight Outta Compton) and his teenage daughter Sydney (STORM REID, HBO’s Euphoria). But when Cecilia’s abusive ex, Adrian (OLIVER JACKSON-COHEN, Netflix’s The Haunting of Hill House), commits suicide and leaves her a generous portion of his vast fortune, Cecilia suspects his death was a hoax. As a series of eerie coincidences turn lethal, threatening the lives of those she loves, Cecilia’s sanity begins to unravel as she desperately tries to prove that she is being hunted by someone nobody can see. JASON BLUM produces The Invisible Man for Blumhouse Productions. The Invisible Man is written, directed and executive produced by LEIGH WHANNELL, one of the original conceivers of the Saw franchise who most recently directed Upgrade and Insidious: Chapter 3. -

JOEL GRIFFEN EDITOR Hijoel.Com

JOEL GRIFFEN EDITOR hiJoel.com FEATURES: UNFOLLOWED Bazelevs Productions Prod: Timur Bekmambetov, Dir: Bryce McGuire Co-Director / Co-Editor Ana Liza Muravina, Adam Sidman THE LEGO MOVIE 2: Warner Bros. Prod: Phil Lord, Christopher Miller Dir: Mike Mitchell THE SECOND PART Additional Editor NEXT LEVEL The Loft Ent. Prod: Lisa McGuire Dir: Ilyssa Goodman FAMILY BLOOD Divide/Conquer Prod: John Lang Dir: Sonny Mallhi CURVATURE 1inMM Productions Prod: Julio Hallivis Dir: Diego Hallivis *Official Selection, SITGES 2017 CULTURE OF FEAR Dark Society Prod: Nick Liam Heaney Dir: Kayla Tabish STEPHANIE Blumhouse Prod: Jason Blum, Bryan Bertino Dir: Akiva Goldsman Storyboard Animatic THE KEEPING HOURS Blumhouse Prod: Jason Blum, John Miranda Dir: Karen Moncrieff Storyboard Animatic SLEIGHT Diablo Ent./Blumhouse Prod: Alex Theurer, Eric B. Fleischman, Dir: JD Dillard *Official Selection, Sundance 2016, NEXT Category Sean Tabibian MAXIMUM RIDE Studio 71 Prod: Gary Binkow, Amee Dolleman Dir: Jay Martin THE BROTHERS GRIMSBY Sony Pictures Prod: Sacha Baron Cohen, Todd Schulman Dir: Louis Leterrier Storyboard Animatic DEAD MAN DOWN IM Global Prod: Neal H. Moritz, J.H. Wyman Dir: Niels Arden Oplev Assistant Editor PARANORMAL ACTIVITY 3 Paramount Prod: Jason Blum, Steven Schneider Dir: Henry Joost, Assistant Editor Oren Peli Ariel Schulman LUCKY Ten/Four Pictures Prod: Caitlin Murney, Gil Cates Jr. Dir: Gil Cates Jr. Assistant Editor RANGO Paramount Prod: John B. Carls, Graham King Dir: Gore Verbinski Assistant Editor SUPER 8 Bad Robot Prod: Bryan Burk, Steven Spielberg Dir: J.J. Abrams Assistant Editor PARANORMAL ACTIVITY 2 Paramount Prod: Jason Blum, Oren Peli Dir: Tod Williams Assistant Editor TELEVISION: KRYPTON (Season 1-2) Warner Horizon/SyFy Prod: Cameron Welsh, David S. -

More at Sutv.Nova.Edu! Follow Us @Sutvch96

Watch all these movies and more at sutv.nova.edu! Movie Show Times: February 1-28, 2018 (954) 262-2602 [email protected] www.nova.edu/sutv Date 12:30a 2:30a 4:30a 6:30a 8:30a 11:00a 1:00p 3:30p 5:30p 8:00p 10:00p The Killing of a Happy Death Thank You for I, Daniel Blake So B It Brad’s Status American Made Breathe The Bachelors Loving Vincent The Foreigner 1-Feb Sacred Deer Day Your Service My Little Pony: The Killing of a Love Beats Blade Runner Brad’s Status Marshall Geostorm Polina It Overdrive The Snowman 2-Feb The Movie Sacred Deer Rhymes 2049 Love Beats My Little Pony: Thank You for Breathe The Bachelors The Foreigner Loving Vincent So B It The Snowman I, Daniel Blake American Made 3-Feb Rhymes The Movie Your Service The Killing of a Happy Death Blade Runner The Bachelors Marshall Breathe Polina Geostorm Overdrive It Brad’s Status 4-Feb Sacred Deer Day 2049 Blade Runner My Little Pony: Love Beats Thank You for Polina Loving Vincent Marshall So B It The Snowman I, Daniel Blake Geostorm 5-Feb 2049 The Movie Rhymes Your Service The Killing of a Thank You for So B It Overdrive Loving Vincent Brad’s Status The Foreigner Breathe American Made The Bachelors It 6-Feb Sacred Deer Your Service The Killing of a My Little Pony: Blade Runner Love Beats Happy Death I, Daniel Blake Overdrive Geostorm Marshall It Polina 7-Feb Sacred Deer The Movie 2049 Rhymes Day My Little Pony: Happy Death Thank You for Brad’s Status I, Daniel Blake Breathe American Made The Bachelors Loving Vincent So B It The Foreigner 8-Feb The Movie Day Your Service Love Beats -

Screendollars Newsletter 2020-11-02.Pdf

For Exhibitors November 2, 2020 Screendollars About Films, the Film Industry No. 141 Newsletter and Cinema Advertising Just past 8pm on October, 30, 1938 Orson Welles delivered his famous deep-fake of the American public when CBS broadcast his radio adaptation of War of the Worlds. Based on the 1898 sci-fi novel by H.G. Welles, the main broadcast presented itself as a live report from New Jersey, where Martians had touched down to invade Earth. Some listeners mistook the broadcast as actual reporting on real events, prompting widespread panic. The next day, the 23-year old Welles spoke to reporters at a hastily arranged press-conference to explain that this outcome was entirely surprising and unintended. However, the attention also made Welles famous, establishing his reputation (Click to Play) as a gifted storyteller with the skill to convince audiences to suspend their disbelief in the incredible, one of the fundamental propositions of Hollywood filmmaking. “When they talked about that [Welles] was embarrassed by it, I don’t think so. If you look at that press conference, he’s so contrite, and he’s just acting his brains out, and he’s so clearly delighted.” - Director John Landis commenting on Welles speaking at the press conference after the 1938 broadcast. Weekend Box Office Results (10/30-11/1) With Commentary by Paul Dergarabedian, Comscore Per Theatre Rank Title Week Theatres Wknd $ Total $ Average $ 1 Come Play (Focus Features) 1 2,183 3,150,000 1,443 3,150,000 2 Honest Thief (Open Road) 4 2,360 1,350,000 572 9,535,262 3 The War with Grandpa (101 Studios) 4 2,365 1,081,416 457 11,289,621 4 Tenet (Warner Bros.) 9 - 885,000 - 53,800,000 5 The Empty Man (20th Century) 2 2,051 561,000 274 2,268,677 6 Hocus Pocus 2020 Re-release (Disney) 5 1130 456,000 404 4,828,000 7 The Nightmare Before Christmas 2020 Re-release (Disney) 3 1222 386,000 316 2,286,000 8 Monsters, Inc.