Achieving Cultural Competence in Vietnamese EFL Classes

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

American Celebration of Music in Vietnam Hanoi – Halong – Saigon – Cu Chi – Tay Ninh

American Celebration of Music in Vietnam Hanoi – Halong – Saigon – Cu Chi – Tay Ninh Standard Tour #3 (8 nights / 10 days) Day 1 Depart via scheduled airline service to Hanoi, Vietnam Day 2 Hanoi (D) Arrive at Hanoi. Meet your MCI Vietnamese Tour Manager, who will assist the group to awaiting chartered motor coach for a transfer to the hotel. Along the way to the hotel, we will enjoy a brief orientation tour of Hoan Kiem Lake, the French Quarter and Old Quarter of Hanoi, time permitting This evening we will attend a Water Puppets performance at the Municipal Water Puppets Theater and a Welcome Dinner at a local restaurant The Vietnamese nation was born among the lagoons and marshes of the Red River Delta around 4000 years ago and for most of its independent existence has been ruled from Hanoi, Vietnam's small, elegant capital lying in the heart of the northern delta. Given the political and historical importance of Hanoi and its burgeoning population of three million, it's still a surprisingly low-key city, with the character of a provincial town Day 3 Hanoi (B,L,D) Following breakfast at the hotel, we will enjoy a city tour with visits to the Temple of Literature, Ho Chi Minh Mausoleum and Presidential Palace, Ho Chi Minh Stilt House, One Pillar Pagoda and the famous “Hanoi Hilton” prison We will have lunch at a local restaurant in Hanoi The afternoon will be spent at our leisure and prepare for this evening performance Evening Concert at Hanoi Opera House as part of the American Celebration of Music in Vietnam Day 4 Hanoi / Halong Bay -

To Review Evidence of a Likely Secret Underground Prison Facility

From: [email protected] Date: June 2, 2009 2:53:54 PM EDT To: [email protected] Cc: [email protected], [email protected], [email protected], [email protected] Subject: Our Memorial Day LSI Request of 5/25/2009 3:44:40 P.M. EDT Sirs, We await word on when we can come to Hanoi and accompany you to inspect the prison discussed in our Memorial Day LSI Request of 5/25/2009 3:44:40 P.M. EDT and in the following attached file. As you see below, this file is appropriately entitled, "A Sacred Place for Both Nations." Sincerely, Former U.S. Rep. Bill Hendon (R-NC) [email protected] Former U.S. Rep. John LeBoutillier (R-NY) [email protected] p.s. You would be ill-advised to attempt another faked, immoral and illegal LSI of this prison like the ones you conducted at Bang Liet in spring 1992; Thac Ba in summer 1993 and Hung Hoa in summer 1995, among others. B. H. J. L. A TIME-SENSITIVE MESSAGE FOR MEMBERS OF THE SENATE SELECT COMMITTEE ON POW/MIA AFFAIRS 1991-1993: SENATOR JOHN F. KERRY, (D-MA), CHAIRMAN SENATOR HARRY REID, (D-NV) SENATOR HERB KOHL (D-WI) SENATOR CHUCK GRASSLEY (R-IA) SENATOR JOHN S. McCAIN, III (R-AZ) AND ALL U.S. SENATORS CONCERNED ABOUT THE SAFETY OF AMERICAN SERVICE PERSONNEL IN INDOCHINA AND THROUGHOUT THE WORLD: http://www.enormouscrime.com "SSC Burn Bag" TWO FORMER GOP CONGRESSMEN REVEAL DAMNING PHOTOS PULLED FROM U.S. SENATE BURN BAG IN 1992; CALL ON SEN. -

Battered Beauties a Research on French

Simone Bijlard Battered Beauties Battered Beauties A research on French colonial markets in Cambodia by Simone Bijlard Colophon Research thesis Battered Beauties By Simone Bijlard Committee members: dr. G. Bracken (research) ir. R.J. Notrott (architecture) ir. E.J. van der Zaag (building technology) Delft University of Technology Department of Architecture MSc 3, 4 Explore Lab March 2011 Preface Large ceiling fans turn lazily overhead, even though home when they drank their own Chardonnay. barbecues sizzle with savoury sausages. the blazing heat has disappeared with the setting of But it is a rêverie, only existing in these few While eating my dessert - a baked banana - I wander the sun. The rhythmic sound of the fans, combined restaurants in the colonial quarter of Phnom Penh. around the stalls of the market. Although the market with my first glass of wine in a while makes me For life in Cambodia has moved on. The French is about to close, there is still much to see. Some comfortably drowsy. I lean backwards in my large left and brought upon the region, one could say, a vendors are desperately trying to sell their last fresh cane armchair and watch the waitresses in their blood-stricken conflict. It resulted in a genocidal produce. I see whole pig’s heads, live tortoises, meticulously tailored dresses pass by. A musician communist regime. colourful heaps of fruit, the latest fashion. plays on a bamboo xylophone, making me even So how much is there to say about the French? Towering above my head is a grand structure, more at ease. -

Must See Places in Hanoi, Vietnam Ho Chi Minh Mausoleum (Open

Must See Places In Hanoi, Vietnam by dailynews Ho Chi Minh Mausoleum (Open mornings only, 8-11am; closed afternoons, Mondays, and Fridays. Admission free.) The city down south may have his name, but only Hanoi has the man himself, entombed in distinctly Lenin-esque fashion - against his wishes, but that's how it goes. No talking, short pants, or other signs of disrespect allowed while viewing; photos are allowed only from outside, in the grand Ba Dinh Square. Purses are allowed into the tomb, but expect them to be searched by several bored soldiers along the way. Left luggage is handled in a complicated scheme: there is an office near the street for large bags, with separate windows for Vietnamese and foreigners, and a further office for cameras, which will be transported to a third office right outside the exit of the mausoleum. Items checked in at the first office, however, will stay there. Note that the mausoleum is closed for a couple months around the end of the year, when the body is taken overseas for maintenance. Ho Chi Minh Museum (19 Ngoc Ha St., Ba Dinh, Hanoi; tel. +84-4 846-3572, fax +84-4 843-9837; Open 8-11:30am, 2-4pm, closed Monday and Friday afternoons. Admission 15,000 dong.) Right around the corner, this gleaming white museum and its gloriously ham-handed iconography are the perfect chaser to the solemnity of the mausoleum. The building, completed in 1990, is intended to evoke a white lotus. Some photos and old letters are on display on the second floor, but the main exhibition space is on the third floor. -

In the Eyes of Foreign Travelers, Hanoi Has Specialty That They Never Find in Any Cities in Asia

In the eyes of foreign travelers, Hanoi has specialty that they never find in any cities in Asia. If you have already booked a ticket and fly to Hanoi with your Vietnam visa. Let’s find out 10 enjoyable places to visit in Hanoi. One Pillar Pagoda Located in the heart of Hanoi, One Pillar Pagoda is an overall extremely unique architecture of Vietnam, also known as the Secret Temple, Lien Hoa Dai or Dien Huu Tu. This temple was built in 1049 to reconstruct a strange dream of the King Ly Thai Tong. It was built between the lake and it has the shape like a lotus flower rising from the lake. The pagoda was damaged greatly during the war. In 1955, the temple was reconstructed based on old architecture and remains until this day. Westlake Located not far from the city center, West Lake is the largest lake in Hanoi and the favorite leisure destination not only for locals but also many tourists. The most appropriate time to visit Westlake is at sunset, when you can participate in exciting activities such as rowing, biking… Particularly, going to West Lake, you have the chance to visit Tran Quoc Pagoda – one of the four most sacred ancient temple of Hanoi. Besides, you can enjoy a lot of special food like Banh tom Ho Tay (Crisp shrimp pastry), pho cuon Ngu Xa (rolled pho), West Lake ice cream, etc... Thang Long Puppet Theatre When travelling to Hanoi, Thang Long Puppet Theater, right near Hoan Kiem Lake is favoured among top places to visit in Hanoi by foreign tourists. -

China / Vietnam 2009

SCHEDULE ON PAGE 4 CHINA & VIETNAM WITH THE CEO CLUBS NEW CHAPTER IN FUZHOU COME DO BUSINESS & HAVE FUN IN . SUN, JUN 21ST TO SAT, JUL 4TH, 2009 It willr bedozen a unique previous experi- trips The CEO CLUBS have developed a series of two day visits to six different cities to make this profitable and fun. ence, unlike any of ou CEO CLUBS, INC Traveling with the CEO CLUBS is like playing 15 BROADSUITE STREET1120 golf; while you may experience guilt pangs, you will actually close more business than during OPPOSITE NEW YORK any other equal time expenditure, STOCKincluding EXCHANGE golf. NEW YORK,T: 212.925.7911 NY 10005-1972 1 F: 212.925.7463 [email protected] LAUNCHING 2 NEW CHAP TERS 14 DAYS & 13 NIGHTS IN CHINA & VIETNAM ($7,000 FOR 2 PEOPLE) Having Fun While Making Money in China & Vietnam As a CEO CLUB member, we want to facili- tate your opportunities to do business (It’s our primary purpose) with our Chinese and Vietnamese members. Many of our previous adventurers are now doing business with new found partners. We will be launching two new chapters in Vietnam. Our delegation will be guests of both of the governments and accorded many extra courtesies. The Chinese govern- ment knows us well and subsidizes a signifi- The CEO Clubs will open new chapters cant portion of our expenses. Hence, these in Fuzhou, China and Hanoi and Saigon prices are subsidized. We will travel as the (Ho Chi Minh City) (HCMC) in Vietnam. five hundred (500) previous CEO CLUB mem- ber have experienced on a dozen earlier vis- We will meet new business partners its; “one step above luxury”. -

Viet Nam “50Th Anniversary Commemoration” Peace Tour March 4 - March 21, 2018

VFP CHAPTER 160 – Hoà Bình (Peace) ANNOUNCING OUR 2018 TOUR VIET NAM “50TH ANNIVERSARY COMMEMORATION” PEACE TOUR MARCH 4 - MARCH 21, 2018 Join us for a 50-year look back at 1968 – the Tet Offensive, Khe Sanh, My Lai – as we travel through Viet Nam, north to south. For the seventh year, Viet Nam's Hoa Binh (Peace) Chapter 160 of Veterans For Peace (VFP) will host a two-week insider tour of a former war-torn country that is now a nation of peace and beauty – Viet Nam. The land is beautiful, the beaches, white sand, and palm trees are inviting, the mountains rugged and resilient – as are the people. The Vietnamese will welcome us with warm embraces and generous spirits. Join VFP for a truly memorable tour, the second experience of a lifetime for Vietnam veterans – and a much better one this time! INTRODUCTION: VFP Chapter 160 is the only American veterans organization with members living and working in Viet Nam, and vets and associate members in the U.S. Our mission is to address the legacies of America’s war. We contribute to the recovery still underway from the war’s consequences: veterans and their families struggling to be safe from unexploded ordnance (UXO), the tragedy of Agent Orange/Dioxin, poverty that is still a burden. PURPOSE: Each tour participant is asked to bring at least $1,000 as a donation which will be pooled at the end of the trip. Participants will vote on how the money is to be disbursed – for bomb clearance and risk education, to help victims of chemical warfare, to support hospitals, orphanages, schools, or other family and community needs. -

Located in the Northern Part of Vietnam, Hanoi Boasts of a Population of 6,238,000 People

Located in the northern part of Vietnam, Hanoi boasts of a population of 6,238,000 people. Hanoi was the center of politics of Vietnam from 1010 to 1802. It was the capital of French Indo-China from 1887 to 1945. It was the capital of North Vietnam from 1945 to 1976. Located on the banks of the Red River, Hanoi boasts of a rich culture and history. History shows that Hanoi was known by different names. After its emancipation from the Japanese clutches in 1945, it became a major seat of governance of the country. The city became the capital of North Vietnam amidst a longstanding tussle between the French and the Vietminh forces. Its communication was severely disrupted during the Vietnam War. Hanoi became the capital of united Vietnam on 2 July, 1976. Hanoi has been on the road to development in recent times. Hanoi is regarded as the cultural capital of Vietnam, absorbing traits of the various dynasties that ruled this land. The cultural and historic remains are huge attractions for tourists and locales alike. Sightseeing in Hanoi is a major attraction for tourists thronging the city in droves. Foreign tourists can get Vietnam visa on arrival at Noi Bai international airport through any travel agency. You can catch amazing sights of the ancient buildings rich in history and culture on sightseeing tours in Hanoi. The serene Hoan Kiem Lake is a major attraction of Hanoi. Ngoc Son on the banks of the lake is another major attraction of Hanoi. The Old Quarter with its 36 winding streets is a lively center located at the north of the lake. -

Real Time Monitoring of Urban Transport – Solutions for Traffic Management and Urban Development in Hanoi

Real Time Monitoring of Urban Transport – Solutions for Traffic Management and Urban Development in Hanoi Real Time Monitoring of Urban Transport - Solutions for Traffic Management and Urban Development in Hanoi Schlussbericht Autoren des Berichts RUIZ LORBACHER, Matias / LE, Quang Son / LÜKE, Marc / THAMM, Hans-Peter / VALEK, Veronika / DINTER, Michael / CHRIST, Ingrid / KRÄMER, Alexander / SOHR, Alexander / SAUERLÄNDER-BIEBL, Anke / BROCKFELD, Elmar / PLEINES, Carolin Vorhabenbezeichnung: CLIENT Vietnam - Verbundprojekt: Real Time Monitoring of Urban Transport - Solutions for Transport Management and Urban Development in Hanoi (REMON) Förderkennzeichen (FKZ): 033RD1103A-H Deutsche Verbundpartner: AS&P – Albert Speer & Partner GmbH, DELPHI IMM GmbH, Deutsches Zentrum für Luft- und Raumfahrt (DLR) e.V., Freie Universität Berlin, Internationale Akademie Berlin für Innovative Pädagogik, Psychologie und Ökonomie gGmbH (INA), Technische Universität Darmstadt, WWL Umweltplanung und Geoinformatik GbR Laufzeit des Vorhabens: 01.08.2012 bis 31.10.2015 Die Verantwortung für den Inhalt dieser Veröffentlichung liegt bei den Autoren. Februar 2016 Schlussbericht Schlussbericht Seite: 1 Inhalt Abkürzungsverzeichnis........................................................................................................... 3 Executive Summary ............................................................................................................... 4 Vorwort ................................................................................................................................ -

RESERVATION FORM – Complete and Mail To: Ms

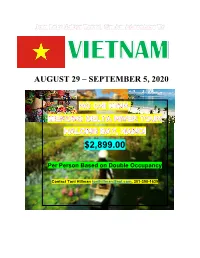

AUGUST 29 – SEPTEMBER 5, 2020 $2,899.00 Per Person Based on Double Occupancy Contact Toni Hillman [email protected], 301-390-1639 ITINERARY Saturday, August 29: Depart for Vietnam Depart Washington, DC Dulles International Airport. Sunday, August 30: Arrive in Ho Chi Minh, Vietnam Arrive in Ho Chi Minh (formerly Saigon), the largest city in Vietnam. Transfer to your hotel and enjoy the balance of the day at leisure. Overnight: Ho Chi Minh Monday, August 31: Ho Chi Minh City Tour Spend morning at leisure. In the afternoon, enjoy half day tour of Ho Chi Minh City, which includes the neo- Romanesque Notre Dame Cathedral, the Central Post Office with its French style architecture, City Hall, and the magnificent Saigon Opera House. From here, visit lively Ben Thanh Market, where an unbelievable assortment of wares and crafts are sold under one roof. Continue to Dong Khoi Street, a major shopping thoroughfare in the center of the city. Early in the evening, enjoy a Welcome Drink and orientation meeting with your Tour Manager. Remainder of the evening is at leisure. Be sure to check out the diversified dining scene in this culinary rich city. Overnight: Ho Chi Minh Meal: Breakfast Tuesday, September 1: Mekong Delta River Tour Today’s journey into the Mekong Delta region will take you along the newly built highway, picturesque countryside and seemingly endless paddy fields. Upon arrival at My Tho, you will board a private motor boat for a fascinating cruise along the river, observing the daily life of local people on the waterways. The tour includes a visit to a coconut factory, handicraft workshop and honey bee farm. -

Vietnam Briefing Packet

VIETNAM PROVIDING COMMUNITY HEALTH TO POPULATIONS MOST IN NEED se P RE-FIELD BRIEFING PACKET VIETNAM 1151 Eagle Drive, Loveland, CO, 80537 | (970) 635-0110 | [email protected] | www.imrus.org VIETNAM Country Briefing Packet Contents ABOUT THIS PACKET 3 BACKGROUND 4 EXTENDING YOUR STAY? 5 HEALTH OVERVIEW 6 COUNTRY OVERVIEW 10 History 10 Geography 12 Climate and Weather 12 Demographics 13 Economy 15 Education 16 Culture 17 Religion 18 Poverty 18 SURVIVAL GUIDE 19 Etiquette 19 Language 21 Safety 24 Currency 26 CURRENT CONVERSATION RATE OF 11 April, 2016 27 IMR RECOMMENDATIONS ON PERSONAL FUNDS 27 Time in Vietnam 28 EMBASSY INFORMATION 28 WEBSITES 30 !2 1151 Eagle Drive, Loveland, CO, 80537 | (970) 635-0110 | [email protected] | www.imrus.org VIETNAM Country Briefing Packet ABOUT THIS PACKET This packet has been created to serve as a resource for the VIETNAM Medical and Dental Team. This packet is information about the country and can be read at your leisure or on the airplane. The first section of this booklet is specific to the areas we will be working near (however, not the actual clinic locations) and contains information you may want to know before the trip. The contents herein are not for distributional purposes and are intended for the use of the team and their families. Sources of the information all come from public record and documentation. You may access any of the information and more updates directly from the World Wide Web and other public sources. !3 1151 Eagle Drive, Loveland, CO, 80537 | (970) 635-0110 | [email protected] | www.imrus.org VIETNAM Country Briefing Packet BACKGROUND The conquest of Vietnam by France began in 1858 and was completed by 1884. -

Hanoi, Vietnam Destination Guide

Hanoi, Vietnam Destination Guide Overview of Hanoi Vietnam's small and vibrant capital lies at the heart of the northern Red River Delta, and is a city of lakes, leafy boulevards and open parks with a French colonial feel. Hanoi was founded in 1010, and became the centre of government for the Indochina Union under French rule in 1888. In 1954 it became the official capital of independent Vietnam. Today ancient crumbling buildings dating from the 11th century lie scattered among grand French colonial residences, while shrines and monuments to Vietnam's first president, Ho Chi Minh, sit in the shadow of modern high-rise buildings. The streets of the Old Quarter preserve age-old customs, where trade takes visitors back half a century, and temples, pagodas and monuments reflect the historic character of Vietnam. Although a city of historical importance, as well as the social and cultural centre of Vietnam, it is a surprisingly modest and charming place, far slower and less developed than Ho Chi Minh City in the south. Hanoi has retained its appealing sense of the old world, despite the onset of a brisk tourism trade in 1993, absorbing the boom of hotels, travellers' hangouts, and the gradual infiltration of western-style food and fashions into the once inaccessible city. As the early morning mist rises from the serene Hoan Kiem Lake, tracksuit-clad elders perform the slow movements of tai chi, like park statues coming to life. Streets fill with activity, mopeds and bicycles weave among pedestrians, while cyclo drivers (three-wheeled bicycle taxis) clamour for attention, and postcard vendors cluster around tourists like bees sensing an open honey pot.