A Manifesto for Transdisciplinary Designers

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

An Environmental Ethic: Has It Taken Hold?

An Environmental Ethic: Has it Taken Hold? arth Da y n11d the creation Eof l·Y /\ i 11 1 ~l70 svrnbolized !he increasing ccrncl~rn of the nation about environmental vulues. i'\o\\'. 18 vears latur. has an cm:ironnrnntal ethic taken hold in our sot:iety'1 This issue of J\ P/\ Jounwl a<lclresscs that questi on and includes a special sc-~ct i un 0 11 n facet of the e11vironme11tal quality effort. l:nvi ron men ta I edur:alion. Thr~ issue begins with an urticln bv Pulitzer Prize-wi~rning journ;ilist and environmentalist J<obert C:;1hn proposing a definition of an e11viro11m<:nlal <~thic: in 1\merica. 1\ Joumol forum follows. with fin: prominnnt e11viro1rnw11tal olJsefl'ers C1n swt:ring tlw question: lws the nthi c: tukn11 hold? l·: P1\ l\dministrnlur I.cc :VI. Tlwm;1s discusses wht:lhcr On Staten Island, Fresh Kills Landfill-the world's largest garbage dump-receives waste from all h;ivc /\1ll(:ric:an incl ivi duals five of New York City's boro ughs. Here a crane unloads waste from barges and loads it onto goll!:11 sc:rious about trucks for distribution elsewhere around the dump site. W illiam C. Franz photo, Staten Island Register. environnwntal prott:c.tion 11s a prn c. ti c:al m.ittc:r in thuir own li v1:s, and a subsnqucmt llroaclening the isst1e's this country up to the River in the nu tion's capital. article ;111alyws the find ings pt:rspective, Cro Hnrlem present: u box provides u On another environnwntal of rl!u:nt public opinion Brundtland. -

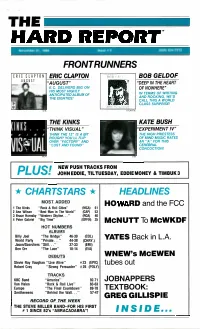

HARD REPORT' November 21, 1986 Issue # 6 (609) 654-7272 FRONTRUNNERS ERIC CLAPTON BOB GELDOF "AUGUST" "DEEP in the HEART E.C

THE HARD REPORT' November 21, 1986 Issue # 6 (609) 654-7272 FRONTRUNNERS ERIC CLAPTON BOB GELDOF "AUGUST" "DEEP IN THE HEART E.C. DELIVERS BIG ON OF NOWHERE" HIS MOST HIGHLY ANTICIPATED ALBUM OF IN TERMS OF WRITING AND ROCKING, WE'D THE EIGHTIES! CALL THIS A WORLD CLASS SURPRISE! ATLANTIC THE KINKS KATE BUSH NINNS . "THINK VISUAL" "EXPERIMENT IV" THINK THE 12" IS A BIT THE HIGH PRIESTESS ROUGH? YOU'LL FLIP OF MIND MUSIC RATES OVER "FACTORY" AND AN "A" FOR THIS "LOST AND FOUND" CEREBRAL CONCOCTION! MCA EMI JN OE HWN PE UD SD Fs RD OA My PLUS! ETTRACKS EDDIE MONEY & TIMBUK3 CHARTSTARS * HEADLINES MOST ADDED HOWARD and the FCC 1 The Kinks "Rock & Roll Cities" (MCA) 61 2 Ann Wilson "Best Man in The World" (CAP) 53 3 Bruce Hornsby "Western Skyline..." (RCA) 40 4 Peter Gabriel "Big Time" (GEFFEN) 35 McNUTT To McWKDF HOT NUMBERS ALBUMS Billy Joel "The Bridge" 46-39 (COL) YATES Back in L.A. World Party "Private. 44-38 (CHRY.) Jason/Scorchers"Still..." 37-33 (EMI) Ben Orr "The Lace" 18-14 (E/A) DEBUTS WNEW's McEWEN Stevie Ray Vaughan "Live Alive" #23(EPIC) tubes out Robert Cray "Strong Persuader" #26 (POLY) TRACKS KBC Band "America" 92-71 JOBNAPPERS Van Halen "Rock & Roll Live" 83-63 Europe "The Final Countdown" 89-78 TEXTBOOK: Smithereens "Behind the Wall..." 57-47 GREG GILLISPIE RECORD OF THE WEEK THE STEVE MILLER BAND --FOR HIS FIRST # 1 SINCE 82's "ABRACADABRA"! INSIDE... %tea' &Mai& &Mal& EtiZiraZ CiairlZif:.-.ZaW. CfMCOLZ &L -Z Cad CcIZ Cad' Ca& &Yet Cif& Ca& Ca& Cge. -

Electric-Rentbook-5.Pdf

England 2 Colombia 0 Electric Rentbook Issue 5 - September 2000 Winners 2 Discs I (each) 8 Ashville Terrace, Cross Hills, Keigh/ey, West Yorkshire, 8020 7LQ. Email: e/ectric.rentbook@talk2l .com Electric Rentman: Graham Scaife Contributors: Thomas Ovens Richard Ellis Ross McMichael Printers: Dixon Target, 21-25 Main Street, Cross Hills, Keighley, West Yorkshire BD20 STX. ongratulations to Steve Jones of Camborne in CCornwall and Jonathan Oak/ey from St. Acknowledgements: Neots in Cambridgeshire. Thank you to the following good They were the lucky winners of our competition to win a signed promo copy of England 2 Colombia O. people: Highly collectable, due to the fact that it isn't going Kirsty MacColI without whom to be released commercially. this fanzine would definitely not Thank you to all the people who entered the be possible. competition, once again a terrific response, and Lisa-Jane Musselbrook at Major don't despair if you weren't a winner this time Minor Management, for her because coming up in future issues of Electric Rentbook we'll have more chances to win Kirsty continued support and help above goodies. and beyond the call of duty. Pete Glenister for taking time out The answers to the questions are as follows:- to answer my questions . I. Kirsty's first single, which was successfully covered by Tracey Ullman was They Don't Know. Teletext on Channel 4 for the 2. A New England was a cover of Billy Bragg's reviews of all issues of ER thus far. song. David Hyde for continued use of 3. -

The History of Rock Music - the Eighties

The History of Rock Music - The Eighties The History of Rock Music: 1976-1989 New Wave, Punk-rock, Hardcore History of Rock Music | 1955-66 | 1967-69 | 1970-75 | 1976-89 | The early 1990s | The late 1990s | The 2000s | Alpha index Musicians of 1955-66 | 1967-69 | 1970-76 | 1977-89 | 1990s in the US | 1990s outside the US | 2000s Back to the main Music page (Copyright © 2009 Piero Scaruffi) Singer-songwriters of the 1980s (These are excerpts from my book "A History of Rock and Dance Music") Female folksingers 1985-88 TM, ®, Copyright © 2005 Piero Scaruffi All rights reserved. Once the effects of the new wave were fully absorbed, it became apparent that the world of singer-songwriters would never be the same again. A conceptual mood had taken over the scene, and that mood's predecessors were precisely the Bob Dylans, the Neil Youngs, the Leonard Cohens, the Tim Buckleys, the Joni Mitchells, who had not been the most popular stars of the 1970s. Instead, they became the reference point for a new generation of "auteurs". Women, in particular, regained the status of philosophical beings (and not only disco-divas or cute front singers) that they had enjoyed with the works of Carole King and Joni Mitchell. Suzy Gottlieb, better known as Phranc (1), was the (Los Angeles-based) songwriter who started the whole acoustic folk revival with her aptly-titled Folksinger (? 1984/? 1985 - nov 1985), whose protest themes and openly homosexual confessions earned her the nickname of "all-american jewish-lesbian folksinger". She embodied the historic meaning of that movement because she was a punkette (notably in Nervous Gender) before she became a folksinger, and because she continued to identify, more than anyone else, with her post- feminist and AIDS-stricken generation in elegies such as Take Off Your Swastika (1989) and Outta Here (1991). -

For Socialist Revolution in the Bastion of World Imperialism!

~ For a Workers Party That Fights for a Workers Government! For Socialist Revolution in the Bastion of World Imperialism! SEE PAGE 2 Organizational Rules. and Gui'delines of theSpartacist League/U.S. ! SEE PAGE 30 Opponents of' the Revolutionary Internationalist Workers Movement SEE PAGE 37 ®~759-C -,t.;'ra viort(ers~arlY·Th8i Fight§lOr'l a Workers Government! For Socialist Revolution in the Bastion of World Imperialism! Programmatic Statement of the Spartacist League/U.S. I. The Spartacist League/U.S., Section of the VI. Full Citizenship Rights for All Immigrants! International Communist League (Fourth Defend the Rights of Racial/Ethnic Minorities! .... 24 Internationalist) .................................... 2 VII. For Women's Liberation Through II. We Are the Party of the Russian Revolution ........ 3 Socialist Revolution! .............................. 25 III. The American Imperialist State and the Tasks VIII. Open the Road to the Youth! ..................... 26 of the Revolutionary Party .......................... 9 IX. For ClaSS-Struggle Defense Against Bourgeois IV. American Capitalism, the Working Class and Repression! ...................................... 27 the Black Question ................................ 13 X. In Defense of Science and the Enlightenment .... 28 V. For a Workers Party That Fights for XI. For a Proletarian Vanguard Party! Reforge the a Workers Government! '" ........................ 19 Fourth International! .............................. 29 I. The Spartacist League/U.S., political/military global hegemony, an ambition which both conditions and is reinforced by the relative political back Section of the International wardness of the American working class. Communist League The U.S. is the only advanced capitalist country lacking a mass workers party representing even a deformed expres (Fourth Internationalist) sion of the political independence of the proletariat. -

Monterey Jazz Festival

DECEMBER 2018 VOLUME 85 / NUMBER 12 President Kevin Maher Publisher Frank Alkyer Editor Bobby Reed Reviews Editor Dave Cantor Contributing Editor Ed Enright Creative Director ŽanetaÎuntová Assistant to the Publisher Sue Mahal Bookkeeper Evelyn Oakes ADVERTISING SALES Record Companies & Schools Jennifer Ruban-Gentile Vice President of Sales 630-359-9345 [email protected] Musical Instruments & East Coast Schools Ritche Deraney Vice President of Sales 201-445-6260 [email protected] Advertising Sales Associate Grace Blackford 630-359-9358 [email protected] OFFICES 102 N. Haven Road, Elmhurst, IL 60126–2970 630-941-2030 / Fax: 630-941-3210 http://downbeat.com [email protected] CUSTOMER SERVICE 877-904-5299 / [email protected] CONTRIBUTORS Senior Contributors: Michael Bourne, Aaron Cohen, Howard Mandel, John McDonough Atlanta: Jon Ross; Austin: Kevin Whitehead; Boston: Fred Bouchard, Frank- John Hadley; Chicago: John Corbett, Alain Drouot, Michael Jackson, Peter Margasak, Bill Meyer, Mitch Myers, Paul Natkin, Howard Reich; Denver: Norman Provizer; Indiana: Mark Sheldon; Iowa: Will Smith; Los Angeles: Earl Gibson, Todd Jenkins, Kirk Silsbee, Chris Walker, Joe Woodard; Michigan: John Ephland; Minneapolis: Robin James; Nashville: Bob Doerschuk; New Orleans: Erika Goldring, David Kunian, Jennifer Odell; New York: Alan Bergman, Herb Boyd, Bill Douthart, Ira Gitler, Eugene Gologursky, Norm Harris, D.D. Jackson, Jimmy Katz, Jim Macnie, Ken Micallef, Dan Ouellette, Ted Panken, Richard Seidel, Tom Staudter, Jack Vartoogian, Michael Weintrob; -

Record of the Week

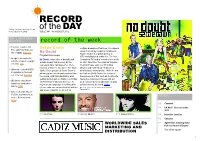

Smiling Dancing Everything Is Free All You Need Is Positivity ISSUE 491 / 16 AUGUST 2012 TOP 5 MUST-READ ARTICLES record of the week TuneCore founders Jeff } Settle Down multiple broadsheet features. The superb Price and Peter Wells exit video directed by longterm collaborator the company. (Billboard) No Doubt Sophie Muller is a global priority at Polydor/Interscope MTV and playlisted at 4Music, The Box, } Google to de-emphasize No Doubt return after a decade with Chartshow TV, and a ‘record of the week’ websites of repeat copyright a radio smash that is every bit the on VH1. Over their five albums together offenders. (FT) comeback fans had hoped for. We’re No Doubt have sold over 45 million hooked, and we’re not alone. The Mark albums and notched up 10 Grammy Universal could sell all EMI } ‘Spike’ Stent produced Settle Down is nominations, winning twice. With the bar if regulators rip ‘the heart picking up an exceptional reaction from set high on Settle Down, the return of out of the deal’ (HypeBot) the media, with Kiss playlisting, and the purveyors of hits such as It’s My Life, getting its first spin on Radio1 on Friday Hella Good and Don’t Speak, will act UK albums chart shows } as Annie Mac’s ‘Special Delivery’. A as a massive dose of adrenalin for pop lowest one week sales in major press campaign is confirmed for junkies around the world. Video. history. (NME) release with covers on a host of fashion Released: September 16 (album; Push and Shove and music magazines, as well as September 24) } 64% of US under 18s use YouTube as primary music CONTENTS source, Nielsen reports. -

Nile Rodgers' Meltdown

Date: Tuesday 13 August 2019 Contact: Phoebe Gardiner, [email protected] / 020 7921 0967 Images: available here Video: available here Nile Rodgers’ Meltdown ‘a radical world party’ - PLUS Meltdown returns: 12-21 June 2020 Nile Rodgers & CHIC, Royal Festival Hall 3 August 2019 © Victor Frankowski for Southbank Centre ★★★★★ “A radical world party… [Rodgers’] nine-day festival wraps its arms around as many ages, genders, sexualities and continents as it can.” - The Guardian Southbank Centre’s 26th Meltdown came to a close Sunday night after its most critically-acclaimed installment yet: nine days of world class music, dance, disco and DJ sets, global exclusives, five-star performances, new talent and free parties attended by thousands, all the design of this year’s curator, the legendary Nile Rodgers. Rodgers says of the experience: “In a life filled with so many unexpected rewards, Meltdown 2019 rises to the level of one of the greatest. I will never forget this experience. And as time goes on the pride for what we've accomplished as a team will only strengthen. I'm overcome with gratitude.” More than 70 acts took over the UK’s largest arts centre from 3-11 August, filling Southbank Centre’s main venues - Royal Festival Hall, Queen Elizabeth Hall and Purcell Room - and every corner of the 17-acre site with music. More than 40 hours of free programming entertained over 8,000 people, including the C’est CHIC Vogue Ball, a Meltdown Mardi Gras and Friday’s And The Beat Goes On, a showcase of talent from the famous BRIT School The curator himself was a ubiquitous presence. -

The Ithacan, 1990-09-06

Ithaca College Digital Commons @ IC The thI acan, 1990-91 The thI acan: 1990/91 to 1999/2000 9-6-1990 The thI acan, 1990-09-06 Ithaca College Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.ithaca.edu/ithacan_1990-91 Recommended Citation Ithaca College, "The thI acan, 1990-09-06" (1990). The Ithacan, 1990-91. 2. http://digitalcommons.ithaca.edu/ithacan_1990-91/2 This Newspaper is brought to you for free and open access by the The thI acan: 1990/91 to 1999/2000 at Digital Commons @ IC. It has been accepted for inclusion in The thI acan, 1990-91 by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ IC. Student Government outlines 'Cornell Collects' adds ambiance !Football opens season aitt Student Congress elections tto American art Albany S1tate ... page 3 ... page 7 ... page 16 The ITHACAN The Newspaper For The Ithaca College Community Vol. 58, No. 2 September 6, 1990 16 pages Free College plans to renovate, expand science space By Kristen Schworm is completed in fall 1992, the four ber. with time, many of these facilities Many factors will be taken into Plans arc underway for Lhc reno science dcpartmcnls: Biology, The new science hall will be have become outdated and a need to consideration concerning the con vaLion of Williams Hall and the Physics, Chemistry, and Psychol equipped with updated technologi update them has become apparent. struction and renovation of these building ofa new science hall. These ogy, will be housed there. cal equipment. The building will In addition, the building also has buildings. The science faculty has plans were devised when the ad The renovation of Williams Hall also contain 22 or 24 new class heating and ventilating difficulties. -

World Party's Debut Is Full of Self- Mockery and Dylan Mimicry Fllflld

THE RETRIEVER FEBRUARY 1Q. 1986 PAGE 3 ENTERTAINMENT Ex-Waterboy's Revolution World Party's debut is full of self- mockery and Dylan mimicry by Jeff Trudell Unfortunately, on Private Revolu- enough style to have a personality of tion, World Party's debut album, its own. In this way it is the only song Don't let the name World Party Wallinger's attempt at eclecticism re- which is reminiscent of Wallinger's fool you — first of all it's not a reggae sults more in disunity than in pleasant days with the Waterboys. And with all band, and second, it's not really a variation. Wallinger's variations seem the vocal styles Wallinger utilizes (half band at all but Karl Wallinger, former a little too diverse to have been com- a dozen?) I would hope that "All bass and keyboard player for The piled into one album. Waterboys. The real question is Come True" represents the definitive Karl Wallinger, and is a vocal style he whether he chose a pseudonym out of Most of the songs on Private Revo- modesty or shame. lution, despite their energy, could be will nurture and perfect in the future when and if he decides to evolve a Wallinger, Welsh by birth, has described as generic pop; which is not personal style (or even a personali- played for The Waterboys on two to say that these songs are wholly albums, A Pagan Place, released in unappealing — "M aking Love (To the ty). 1984, and This is the Sea, released in World)" and "This is the Sea" can be "It Can Be Beautiful" and "Dance 1985, both on Island records. -

PARTY RULES? Dilemmas of Political Party Regulation in Australia

PARTY RULES? Dilemmas of political party regulation in Australia PARTY RULES? Dilemmas of political party regulation in Australia Edited by Anika Gauja and Marian Sawer Published by ANU Press The Australian National University Acton ACT 2601, Australia Email: [email protected] This title is also available online at press.anu.edu.au National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry Title: Party rules? : dilemmas of political party regulation in Australia / editors: Anika Gauja, Marian Sawer. ISBN: 9781760460761 (paperback) 9781760460778 (ebook) Subjects: Political parties--Australia. Political parties--Law and legislation--Australia. Political participation--Australia. Australia--Politics and government. Other Creators/Contributors: Gauja, Anika, editor. Sawer, Marian, 1946- editor. Dewey Number: 324.2994 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher. Cover design and layout by ANU Press. This edition © 2016 ANU Press Contents Figures . vii Tables . ix Abbreviations . xi Acknowledgements . xiii Contributors . xv 1 . Party rules: Promises and pitfalls . 1 Marian Sawer and Anika Gauja 2 . Resisting legal recognition and regulation: Australian parties as rational actors? . 37 Sarah John 3 . Party registration and political participation: Regulating small and ‘micro’ parties . .73 Norm Kelly 4 . Who gets what, when and how: The politics of resource allocation to parliamentary parties . 101 Yvonne Murphy 5 . Putting the cartel before the house? Public funding of parties in Queensland . 123 Graeme Orr 6 . More regulated, more level? Assessing the impact of spending and donation caps on Australian State elections . -

Political Parties in the Digital Age: a Comparative Review of Digital Technology in Campaigns Around the World

Political Parties in the Digital Age: A Comparative Review of Digital Technology in Campaigns Around the World Edited by Jan Surotchak and Geoffrey Macdonald Source: IRI Political Parties in the Digital Age: A Comparative Review of Digital Technology in Campaigns Around the World Copyright © 2020 Consortium for Elections and Political Process Strengthening (CEPPS) and International Republican Institute (IRI). All rights reserved. Portions of this work may be reproduced and/or translated for non-commercial purposes provided CEPPS is acknowledged as the source of the material and is sent copies of any translation. Send copies to: : Attention: CEPPS Administrative Director Consortium for Elections and Political Process Strengthening 1225 Eye Street NW, Suite 800 Washington, DC 20005 [email protected] Disclaimer: This publication was made possible through the generous support of the American people through the United States Agency for International Development (USAID). The opinions expressed herein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of USAID. ABOUT CEPPS Established in 1995, the Consortium for Elections and Political Process Strengthening (CEPPS) pools the expertise of three international organizations dedicated to democratic development: the International Foundation for Electoral Systems (IFES), the International Republican Institute (IRI), and the National Democratic Institute (NDI). CEPPS has a 20-year track record of collaboration and leadership in democracy, human rights and governance support, learning from experience, and adopting new approaches and tools based on the ever-evolving technological landscape. As mission-driven, non-profit democracy organizations, IFES, IRI and NDI differ from many development actors by maintaining long-term relationships with political parties, election- management bodies, parliaments, civil-society organizations and democracy activists.