Writing Songs and Writing a Record: Inside the Composition of an Acoustic Pop Album

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bobby Alu Short Biography Amidst Smooth Harmonies, Rhythms

Bobby Alu Short Biography Amidst smooth harmonies, rhythms inspired by a strong family lineage of Polynesian performance, and unassuming grooves that work a gradual, smile-inducing high through even a casual listener, Bobby Alu tunes have a way of sneaking into the subconscious and taking up residence. Every now and then, one will pop up as a toe-tapping reminder to take it slow, enjoy the ride. It’s the curator of calm’s way – deliver island-time vibes with gentle optimism rather than forceful instruction, and encourage the type of reflection best achieved in a hammock. Though it’s not all palm trees and daydreams – there’s a robust energy in Alu’s mastery of traditional Samoan log drums, and a vitality to his songwriting that nods to world, roots and pop intelligence. Full biography Move. And be moved. Find your flow and go about each day to the rhythm of your own making. That’s the theme of Byron Bay singer, ukulele strummer and drummer Bobby Alu. Amidst smooth harmonies, rhythms inspired by a strong family lineage of Polynesian performance, and unassuming grooves that work a gradual, smile-inducing high through even a casual listener, Bobby Alu tunes have a way of sneaking into the subconscious and taking up residence. Every now and then, one will pop up as a toe-tapping reminder to take it slow, enjoy the ride. It’s the curator of calm’s way – deliver island-time vibes with gentle optimism rather than forceful instruction, and encourage the type of reflection best achieved in a hammock. -

Paul Clarke Song List

Paul Clarke Song List Busby Marou – Biding my time Foster the People – Pumped up Kicks Boy & Bear – Blood to gold Kings of Leon – Sex on Fire, Radioactive, The Bucket The Wombats – Tokyo (vampires & werewolves) Foo Fighters – Times like these, All my life, Big Me, Learn to fly, See you Pete Murray – Class A, Better Days, So beautiful, Opportunity La Roux – Bulletproof John Butler Trio – Betterman, Better than Mark Ronson – Somebody to Love Me Empire of the Sun – We are the People Powderfinger – Sunsets, Burn your name, My Happiness Mumford and Sons – Little Lion man Hungry Kids of Hungary Scattered Diamonds SIA – Clap your hands Art Vs Science – Friend in the field Jack Johnson – Flake, Taylor, Wasting time Peter, Bjorn and John – Young Folks Faker – This Heart attack Bernard Fanning – Wish you well, Song Bird Jimmy Eat World – The Middle Outkast – Hey ya Neon Trees – Animal Snow Patrol – Chasing cars Coldplay – Yellow, The Scientist, Green Eyes, Warning Sign, The hardest part Amy Winehouse – Rehab John Mayer – Your body is a wonderland, Wheel Red Hot Chilli Peppers – Zephyr, Dani California, Universally Speaking, Soul to squeeze, Desecration song, Breaking the Girl, Under the bridge Ben Harper – Steal my kisses, Burn to shine, Another lonely Day, Burn one down The Killers – Smile like you mean it, Read my mind Dane Rumble – Always be there Eskimo Joe – Don’t let me down, From the Sea, New York, Sarah Aloe Blacc – Need a dollar Angus & Julia Stone – Mango Tree, Big Jet Plane Bob Evans – Don’t you think -

Songs by Artist

DJ Song list Songs by Artist DJ Song list Title Versions Title Versions Title Versions Title Versions -- 360 Ft Pez 50 Cent Adam & The Ants Al Green -- 360 Ft Pez - Live It Up DJ 21 Questions DJ Ant Music DJ Let's Stay Together We -- Chris Brown Ft Lil Wayne Candy Shop DJ Goody Two Shoes DJ Al Stuart -- Chris Brown Ft Lil Wayne - DJ Hustler's Ambition DJ Stand And Deliver DJ Year Of The Cat DJ Loyal If I Can't DJ Adam Clayton & Larry Mullen Alan Jackson -- Illy In Da Club DJ Theme From Mission DJ Hi Chattahoochee DJ -- Illy - Tightrope (Clean) DJ Just A Li'l Bit DJ Impossible Don't Rock The Jukebox DJ -- Jason Derulo Ft Snoop Dog 50 Cent Feat Justin Timberlake Adam Faith Gone Country DJ -- Jason Derulo Ft Snoop Dog DJ Ayo Technology DJ Poor Me DJ Livin' On Love DJ - Wiggle 50 Cent Feat Mobb Deep Adam Lambert Alan Parsons Project -- Th Amity Afflication Outta Control DJ Adam Lambert - Better Than I DJ Eye In The Sky 2010 Remix DJ -- Th Amity Afflication - Dont DJ Know Myself 50 Cent Ft Eminem & Adam Levin Alanis Morissette Lean On Me(Warning) If I Had You DJ 50 Cent Ft Eminem & Adam DJ Hand In My Pocket DJ - The Potbelleez Whataya Want From Me Ch Levine - My Life (Edited) Ironic DJ Shake It - The Potbelleez DJ Adam Sandler 50Cent Feat Ne-Yo You Oughta Know DJ (Beyonce V Eurythmics Remix (The Wedding Singer) I DJ Baby By Me DJ Alannah Myles Sweet Dreams DJ Wanna Grow Old With You 60 Ft Gossling Black Velvet DJ 01 - Count On Me - Bruno Marrs Adele 360 Ft Gossling - Price Of DJ Albert Lennard Count On Me - Bruno Marrs DJ Fame Adele - Skyfall DJ Springtime In L.A. -

Elton John Tumbleweed Connection Mp3, Flac, Wma

Elton John Tumbleweed Connection mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Rock / Pop Album: Tumbleweed Connection Country: Japan Released: 2001 Style: Ballad, Classic Rock MP3 version RAR size: 1542 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1114 mb WMA version RAR size: 1806 mb Rating: 4.2 Votes: 445 Other Formats: WMA MIDI AUD MP4 APE XM ASF Tracklist Hide Credits Ballad Of A Well Known Gun Acoustic Guitar, Lead Guitar – Caleb QuayeBacking Vocals – Dusty Springfield, Kay A1 4:59 Garner, Lesley Duncan, Madeline Bell, Tony Burrows, Tony HazzardBass Guitar – Dave Glover*Drums, Percussion – Roger PopePiano – Elton John Come Down In Time A2 Acoustic Bass – Chris LaurenceAcoustic Guitar – Les ThatcherBass Guitar – Herbie 3:25 FlowersDrums – Barry MorganHarp – Skaila KangaOboe – Karl Jenkins Country Comfort Acoustic Guitar – Caleb QuayeAcoustic Guitar [12-String] – Les ThatcherBacking Vocals – A3 5:08 Dee Murray, Nigel OlssonBass Guitar – Herbie FlowersDrums – Barry MorganHarmonica – Ian DuckPiano – Elton JohnSteel Guitar – Gordon HuntleyViolin – Johnny Van Derek Son Of Your Father Backing Vocals – Kay Garner, Lesley Duncan, Madeline Bell, Sue And Sunny*, Tammi A4 3:46 HuntBass Guitar – Dave Glover*Drums – Roger PopeHarmonica – Ian DuckLead Guitar – Caleb QuayePiano – Elton John My Father's Gun Backing Vocals – Dusty Springfield, Kay Garner, Lesley Duncan, Madeline Bell, Tony A5 6:19 Burrows, Tony HazzardBass Guitar – Dave Glover*Drums – Roger PopeElectric Guitar, Acoustic Guitar – Caleb QuayePiano – Elton John Where To Now St. Peter B1 Backing Vocals -

Song Pack Listing

TRACK LISTING BY TITLE Packs 1-86 Kwizoke Karaoke listings available - tel: 01204 387410 - Title Artist Number "F" You` Lily Allen 66260 'S Wonderful Diana Krall 65083 0 Interest` Jason Mraz 13920 1 2 Step Ciara Ft Missy Elliot. 63899 1000 Miles From Nowhere` Dwight Yoakam 65663 1234 Plain White T's 66239 15 Step Radiohead 65473 18 Til I Die` Bryan Adams 64013 19 Something` Mark Willis 14327 1973` James Blunt 65436 1985` Bowling For Soup 14226 20 Flight Rock Various Artists 66108 21 Guns Green Day 66148 2468 Motorway Tom Robinson 65710 25 Minutes` Michael Learns To Rock 66643 4 In The Morning` Gwen Stefani 65429 455 Rocket Kathy Mattea 66292 4Ever` The Veronicas 64132 5 Colours In Her Hair` Mcfly 13868 505 Arctic Monkeys 65336 7 Things` Miley Cirus [Hannah Montana] 65965 96 Quite Bitter Beings` Cky [Camp Kill Yourself] 13724 A Beautiful Lie` 30 Seconds To Mars 65535 A Bell Will Ring Oasis 64043 A Better Place To Be` Harry Chapin 12417 A Big Hunk O' Love Elvis Presley 2551 A Boy From Nowhere` Tom Jones 12737 A Boy Named Sue Johnny Cash 4633 A Certain Smile Johnny Mathis 6401 A Daisy A Day Judd Strunk 65794 A Day In The Life Beatles 1882 A Design For Life` Manic Street Preachers 4493 A Different Beat` Boyzone 4867 A Different Corner George Michael 2326 A Drop In The Ocean Ron Pope 65655 A Fairytale Of New York` Pogues & Kirsty Mccoll 5860 A Favor House Coheed And Cambria 64258 A Foggy Day In London Town Michael Buble 63921 A Fool Such As I Elvis Presley 1053 A Gentleman's Excuse Me Fish 2838 A Girl Like You Edwyn Collins 2349 A Girl Like -

![COMPLETE MUSIC LIST by ARTIST ] [ No of Tunes = 6773 ]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/5125/complete-music-list-by-artist-no-of-tunes-6773-465125.webp)

COMPLETE MUSIC LIST by ARTIST ] [ No of Tunes = 6773 ]

[ COMPLETE MUSIC LIST by ARTIST ] [ No of Tunes = 6773 ] 001 PRODUCTIONS >> BIG BROTHER THEME 10CC >> ART FOR ART SAKE 10CC >> DREADLOCK HOLIDAY 10CC >> GOOD MORNING JUDGE 10CC >> I'M NOT IN LOVE {K} 10CC >> LIFE IS A MINESTRONE 10CC >> RUBBER BULLETS {K} 10CC >> THE DEAN AND I 10CC >> THE THINGS WE DO FOR LOVE 112 >> DANCE WITH ME 1200 TECHNIQUES >> KARMA 1910 FRUITGUM CO >> SIMPLE SIMON SAYS {K} 1927 >> IF I COULD {K} 1927 >> TELL ME A STORY 1927 >> THAT'S WHEN I THINK OF YOU 24KGOLDN >> CITY OF ANGELS 28 DAYS >> SONG FOR JASMINE 28 DAYS >> SUCKER 2PAC >> THUGS MANSION 3 DOORS DOWN >> BE LIKE THAT 3 DOORS DOWN >> HERE WITHOUT YOU {K} 3 DOORS DOWN >> KRYPTONITE {K} 3 DOORS DOWN >> LOSER 3 L W >> NO MORE ( BABY I'M A DO RIGHT ) 30 SECONDS TO MARS >> CLOSER TO THE EDGE 360 >> LIVE IT UP 360 >> PRICE OF FAME 360 >> RUN ALONE 360 FEAT GOSSLING >> BOYS LIKE YOU 3OH!3 >> DON'T TRUST ME 3OH!3 FEAT KATY PERRY >> STARSTRUKK 3OH!3 FEAT KESHA >> MY FIRST KISS 4 THE CAUSE >> AIN'T NO SUNSHINE 4 THE CAUSE >> STAND BY ME {K} 4PM >> SUKIYAKI 5 SECONDS OF SUMMER >> DON'T STOP 5 SECONDS OF SUMMER >> GIRLS TALK BOYS {K} 5 SECONDS OF SUMMER >> LIE TO ME {K} 5 SECONDS OF SUMMER >> SHE LOOKS SO PERFECT 5 SECONDS OF SUMMER >> SHE'S KINDA HOT {K} 5 SECONDS OF SUMMER >> TEETH 5 SECONDS OF SUMMER >> WANT YOU BACK 5 SECONDS OF SUMMER >> YOUNGBLOOD {K} 50 CENT >> 21 QUESTIONS 50 CENT >> AYO TECHNOLOGY 50 CENT >> CANDY SHOP 50 CENT >> IF I CAN'T 50 CENT >> IN DA CLUB 50 CENT >> P I M P 50 CENT >> PLACES TO GO 50 CENT >> WANKSTA 5000 VOLTS >> I'M ON FIRE 5TH DIMENSION -

Popular Music and Society Artists As Entrepreneurs, Fans As Workers

This article was downloaded by: [James Madison University] On: 03 November 2014, At: 16:54 Publisher: Routledge Informa Ltd Registered in England and Wales Registered Number: 1072954 Registered office: Mortimer House, 37-41 Mortimer Street, London W1T 3JH, UK Popular Music and Society Publication details, including instructions for authors and subscription information: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/rpms20 Artists as Entrepreneurs, Fans as Workers Jeremy Wade Morris Published online: 15 May 2013. To cite this article: Jeremy Wade Morris (2014) Artists as Entrepreneurs, Fans as Workers, Popular Music and Society, 37:3, 273-290, DOI: 10.1080/03007766.2013.778534 To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/03007766.2013.778534 PLEASE SCROLL DOWN FOR ARTICLE Taylor & Francis makes every effort to ensure the accuracy of all the information (the “Content”) contained in the publications on our platform. However, Taylor & Francis, our agents, and our licensors make no representations or warranties whatsoever as to the accuracy, completeness, or suitability for any purpose of the Content. Any opinions and views expressed in this publication are the opinions and views of the authors, and are not the views of or endorsed by Taylor & Francis. The accuracy of the Content should not be relied upon and should be independently verified with primary sources of information. Taylor and Francis shall not be liable for any losses, actions, claims, proceedings, demands, costs, expenses, damages, and other liabilities whatsoever or howsoever caused arising directly or indirectly in connection with, in relation to or arising out of the use of the Content. This article may be used for research, teaching, and private study purposes. -

[email protected] Website: Nightshift.Oxfordmusic.Net Free Every Month

email: [email protected] website: nightshift.oxfordmusic.net Free every month. NIGHTSHIFT Issue 122 September Oxford’s Music Magazine 2005 SupergrassSupergrassSupergrass on a road less travelled plus 4-Page Truck Festival Review - inside NIGHTSHIFT: PO Box 312, Kidlington, OX5 1ZU. Phone: 01865 372255 NEWNEWSS Nightshift: PO Box 312, Kidlington, OX5 1ZU Phone: 01865 372255 email: [email protected] THE YOUNG KNIVES won You Now’, ‘Water and Wine’ and themselves a coveted slot at V ‘Gravity Flow’. In addition, the CD Festival last month after being comes with a bonus DVD which picked by Channel 4 and Virgin features a documentary following Mobile from over 1,000 new bands Mark over the past two years as he to open the festival on the Channel recorded the album, plus alternative 4 stage, alongside The Chemical versions of some tracks. Brothers, Doves, Kaiser Chiefs and The Magic Numbers. Their set was THE DOWNLOAD appears to have then broadcast by Channel 4. been given an indefinite extended Meanwhile, the band are currently in run by the BBC. The local music the studio with producer Andy Gill, show, which is broadcast on BBC recording their new single, ‘The Radio Oxford 95.2fm every Saturday THE MAGIC NUMBERS return to Oxford in November, leading an Decision’, due for release on from 6-7pm, has had a rolling impressive list of big name acts coming to town in the next few months. Transgressive in November. The monthly extension running through After their triumphant Truck Festival headline set last month, The Magic th Knives have also signed a publishing the summer, and with the positive Numbers (pictured) play at Brookes University on Tuesday 11 October. -

Robert Hunter (Huntersbx) on Twitter

Robert Hunter (HunterSBX) on Twitter http://twitter.com/ Twitter Search Home Profile Messages Who To Follow AliaK Settings Help Switch to Old Twitter Sign out New Tweet Robert Hunter @HunterSBX Perth Western Australia Rapper, a parent to a Son named Marley. A cancer patient. That's what I am. Message Following Unfollow Timeline Favorites Following Followers Lists » HunterSBX Robert Hunter @ @I_Am_Simplex Kirks massive BBQ bonananza! Was just Trials, Daz, Kirk, me, a digital 1 of 134 20/04/11 1:50 PM Robert Hunter (HunterSBX) on Twitter http://twitter.com/ camera, 3 cartons of Pale. 21 minutes ago Favorite Retweet Reply » HunterSBX Robert Hunter @ @funkoars the confusion of being in a photo within a photo of your own penis is something that will always confuse me. #scaredofthedick 26 minutes ago Favorite Retweet Reply » HunterSBX Robert Hunter I didn't make, fund, or have anything to do with said Doco, I just consented to them following me around. I am honored that they did but. 31 minutes ago Favorite Retweet Reply » HunterSBX Robert Hunter @ @funkoars yeh no shit hey! That's an integral part of the whole picture! Hahah! I'm just glad they don't have too much footage of my penis 33 minutes ago Favorite Retweet Reply » HunterSBX Robert Hunter Check this video out -- Hunter: The Documentary (short teaser) youtube.com/watch?v=LVNc8b… via @youtube <~~ pretty strange feeling. 1 hour ago Unfavorite Undo Retweet Reply » HunterSBX Robert Hunter Exclusive: Drapht''s "Sing It (The Life of Riley)" music video - NovaFM Videos novafm.com.au/video_exclusiv… <-- good shit! 1 hour ago Favorite Retweet Reply » HunterSBX Robert Hunter Turned on the computer and lost all inspiration to write... -

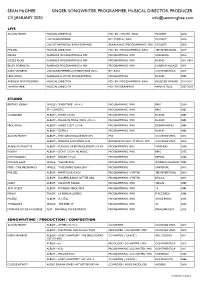

CV JANUARY 2020 [email protected]

SEAN McGHEE SINGER, SONGWRITER, PROGRAMMER, MUSICAL DIRECTOR, PRODUCER. CV JANUARY 2020 [email protected] LIVE ALISON MOYET MUSICAL DIRECTOR MD / BV / SYNTHS / BASS MODEST! 2018- LIVE BAND MEMBER BV / SYNTHS / BASS MODEST! 2013- LIVE SET ARRANGER & PROGRAMMER ARRANGING / PROGRAMMING / MIX MODEST! 2013- PHILDEL MUSICAL DIRECTOR MD / BV / PROGRAMMING / BASS YEE INVENTIONS 2019 KIESZA PLAYBACK PROGRAMMING & MIX PROGRAMMING / MIX UNIVERSAL 2014 RIZZLE KICKS PLAYBACK PROGRAMMING & MIX PROGRAMMING / MIX ISLAND 2011-2014 BLUEY ROBINSON PLAYBACK PROGRAMMING & MIX PROGRAMMING / MIX LONDON VILLAGE 2013 KATE HAVNEVIK LIVE BAND MEMBER (CHINESE TOUR 2015) BV / BASS CONTINENTICA 2015 FROU FROU PLAYBACK & SYNTH PROGRAMMING PROGRAMMING ISLAND 2003 ANDREW MONTGOMERY MUSICAL DIRECTOR MD / BV / PROGRAMMING / BASS RULED BY DREAMS 2014-2015 TEMPOSHARK MUSICAL DIRECTOR MD / PROGRAMMING PAPER & GLUE 2007-2010 STUDIO BRITNEY SPEARS SINGLE – “EVERYTIME” (UK #1) PROGRAMMING / MIX BMG 2004 EP – CHAOTIC PROGRAMMING / MIX BMG 2005 SUGABABES ALBUM – THREE (UK #3) PROGRAMMING / MIX ISLAND 2003 ALBUM – TALLER IN MORE WAYS (UK #1) PROGRAMMING / MIX ISLAND 2005 FROU FROU ALBUM – SHREK 2 OST (US #8) PROGRAMMING / MIX DREAMWORKS 2004 ALBUM – DETAILS PROGRAMMING / MIX ISLAND 2002 ALISON MOYET ALBUM – THE TURN: DELUXE EDITION MIX COOKING VINYL 2015 ALBUM – MINUTES & SECONDS LIVE BACKING VOCALS / SYNTHS / MIX COOKING VINYL 2014 ALANIS MORISSETTE ALBUM – FLAVORS OF ENTANGLEMENT (US #8) PROGRAMMING / BVs WARNERS 2008 ROBYN ALBUM – DON’T STOP THE MUSIC PROGRAMMING / MIX BMG -

Zen in the Art of Writing – Ray Bradbury

A NOTE ABOUT THE AUTHOR Ray Bradbury has published some twenty-seven books—novels, stories, plays, essays, and poems—since his first story appeared when he was twenty years old. He began writing for the movies in 1952—with the script for his own Beast from 20,000 Fathoms. The next year he wrote the screenplays for It Came from Outer Space and Moby Dick. And in 1961 he wrote Orson Welles's narration for King of Kings. Films have been made of his "The Picasso Summer," The Illustrated Man, Fahrenheit 451, The Mar- tian Chronicles, and Something Wicked This Way Comes, and the short animated film Icarus Montgolfier Wright, based on his story of the history of flight, was nominated for an Academy Award. Since 1985 he has adapted his stories for "The Ray Bradbury Theater" on USA Cable television. ZEN IN THE ART OF WRITING RAY BRADBURY JOSHUA ODELL EDITIONS SANTA BARBARA 1996 Copyright © 1994 Ray Bradbury Enterprises. All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. Owing to limitations of space, acknowledgments to reprint may be found on page 165. Published by Joshua Odell Editions Post Office Box 2158, Santa Barbara, CA 93120 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Bradbury, Ray, 1920— Zen in the art of writing. 1. Bradbury, Ray, 1920- —Authorship. 2. Creative ability.3. Authorship. 4. Zen Buddhism. I. Title. PS3503. 167478 1989 808'.os 89-25381 ISBN 1-877741-09-4 Printed in the United States of America. Designed by The Sarabande Press TO MY FINEST TEACHER, JENNET JOHNSON, WITH LOVE CONTENTS PREFACE xi THE JOY OF WRITING 3 RUN FAST, STAND STILL, OR, THE THING AT THE TOP OF THE STAIRS, OR, NEW GHOSTS FROM OLD MINDS 13 HOW TO KEEP AND FEED A MUSE 31 DRUNK, AND IN CHARGE OF A BICYCLE 49 INVESTING DIMES: FAHRENHEIT 451 69 JUST THIS SIDE OF BYZANTIUM: DANDELION WINE 79 THE LONG ROAD TO MARS 91 ON THE SHOULDERS OF GIANTS 99 THE SECRET MIND 111 SHOOTING HAIKU IN A BARREL 125 ZEN IN THE ART OF WRITING 139 . -

Roxy Music to Play a Day on the Green with Original Line up Including the Legendary Bryan Ferry

Media Release: Thursday 18 th November ROXY MUSIC TO PLAY A DAY ON THE GREEN WITH ORIGINAL LINE UP INCLUDING THE LEGENDARY BRYAN FERRY With support from Nathan Haines Roundhouse Entertainment and Andrew McManus Presents is proud to announce that Roxy Music, consisting of vocalist Bryan Ferry, guitarist Phil Manzanera, saxophonist Andy Mackay and the great Paul Thompson on drums, are coming to New Zealand for one A Day On The Green show only at Villa Maria Estate Winery on Sunday 6 th March. Roxy Music will perform material from their entire catalogue including such hits as, Dance Away , Avalon , Let's Stick Together, Take A Chance With Me , Do the Strand , Angel Eyes , Oh Yeah , In the Midnight Hour , Jealous Guy, Love Is The Drug , More Than This and many more. Distinguished by their visual and musical sophistication and their preoccupation with style and glamour Roxy Music were highly influential, as leading proponents of the more experimental element of glam rock as well as a significant influence on early English punk music. They also provided a model for many new wave acts and the experimental electronic groups of the early 1980s. In 2004, Rolling Stone Magazine ranked Roxy Music on its list of the 100 Greatest Artists of All Time and the band are regarded as one of the most influential art-rock bands in music history. Roxy Music exploded onto the scene in 1972 with their progressive self-titled debut album. The sound challenged the constraints of pop music and was lauded by critics and popular among fans, peaking at #4 on the UK album charts.