Digital Disruption and Its Implications in Generating 'Impact' Through Film

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

In the Same Breath

IN THE SAME BREATH A film by Nanfu Wang #InTheSameBreathHBO DEBUTS 2021 ON HBO SUNDANCE FILM FESTIVAL SCREENING SCHEDULE Thursday, January 28 at 5:00 PM PT / 6:00 PM MT – Online (WORLD PREMIERE) For press materials, please visit: ftp://ftp.homeboxoffice.com username: documr password: qq3DjpQ4 Running Time: 95 min Press Contact Press Contact HBO Documentary Films Cinetic Marketing Asheba Edghill / Hayley Hanson Rachel Allen / Ryan Werner Asheba cell: 347-721-1539 Rachel cell: 937-241-9737 Hayley cell: 201-207-7853 Ryan cell: 917-254-7653 [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] LOGLINE Nanfu Wang's deeply personal IN THE SAME BREATH recounts the origin and spread of the novel coronavirus from the earliest days of the outbreak in Wuhan to its rampage across the United States. SHORT SYNOPSIS IN THE SAME BREATH, directed by Nanfu Wang (“One Child Nation”), recounts the origin and spread of the novel coronavirus from the earliest days of the outbreak in Wuhan to its rampage across the United States. In a deeply personal approach, Wang, who was born in China and now lives in the United States, explores the parallel campaigns of misinformation waged by leadership and the devastating impact on citizens of both countries. Emotional first-hand accounts and startling, on-the-ground footage weave a revelatory picture of cover-ups and misinformation while also highlighting the strength and resilience of the healthcare workers, activists and family members who risked everything to communicate the truth. DIRECTOR’S STATEMENT I spent a lot of my childhood in hospitals taking care of my father, who had rheumatic heart disease. -

Pr-Dvd-Holdings-As-Of-September-18

CALL # LOCATION TITLE AUTHOR BINGE BOX COMEDIES prmnd Comedies binge box (includes Airplane! --Ferris Bueller's Day Off --The First Wives Club --Happy Gilmore)[videorecording] / Princeton Public Library. BINGE BOX CONCERTS AND MUSICIANSprmnd Concerts and musicians binge box (Includes Brad Paisley: Life Amplified Live Tour, Live from WV --Close to You: Remembering the Carpenters --John Sebastian Presents Folk Rewind: My Music --Roy Orbison and Friends: Black and White Night)[videorecording] / Princeton Public Library. BINGE BOX MUSICALS prmnd Musicals binge box (includes Mamma Mia! --Moulin Rouge --Rodgers and Hammerstein's Cinderella [DVD] --West Side Story) [videorecording] / Princeton Public Library. BINGE BOX ROMANTIC COMEDIESprmnd Romantic comedies binge box (includes Hitch --P.S. I Love You --The Wedding Date --While You Were Sleeping)[videorecording] / Princeton Public Library. DVD 001.942 ALI DISC 1-3 prmdv Aliens, abductions & extraordinary sightings [videorecording]. DVD 001.942 BES prmdv Best of ancient aliens [videorecording] / A&E Television Networks History executive producer, Kevin Burns. DVD 004.09 CRE prmdv The creation of the computer [videorecording] / executive producer, Bob Jaffe written and produced by Donald Sellers created by Bruce Nash History channel executive producers, Charlie Maday, Gerald W. Abrams Jaffe Productions Hearst Entertainment Television in association with the History Channel. DVD 133.3 UNE DISC 1-2 prmdv The unexplained [videorecording] / produced by Towers Productions, Inc. for A&E Network executive producer, Michael Cascio. DVD 158.2 WEL prmdv We'll meet again [videorecording] / producers, Simon Harries [and three others] director, Ashok Prasad [and five others]. DVD 158.2 WEL prmdv We'll meet again. Season 2 [videorecording] / director, Luc Tremoulet producer, Page Shepherd. -

Co-Optation of the American Dream: a History of the Failed Independent Experiment

Cinesthesia Volume 10 Issue 1 Dynamics of Power: Corruption, Co- Article 3 optation, and the Collective December 2019 Co-optation of the American Dream: A History of the Failed Independent Experiment Kyle Macciomei Grand Valley State University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.gvsu.edu/cine Recommended Citation Macciomei, Kyle (2019) "Co-optation of the American Dream: A History of the Failed Independent Experiment," Cinesthesia: Vol. 10 : Iss. 1 , Article 3. Available at: https://scholarworks.gvsu.edu/cine/vol10/iss1/3 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by ScholarWorks@GVSU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Cinesthesia by an authorized editor of ScholarWorks@GVSU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Macciomei: Co-optation of the American Dream Independent cinema has been an aspect of the American film industry since the inception of the art form itself. The aspects and perceptions of independent film have altered drastically over the years, but in general it can be used to describe American films produced and distributed outside of the Hollywood major studio system. But as American film history has revealed time and time again, independent studios always struggle to maintain their freedom from the Hollywood industrial complex. American independent cinema has been heavily integrated with major Hollywood studios who have attempted to tap into the niche markets present in filmgoers searching for theatrical experiences outside of the mainstream. From this, we can say that the American independent film industry has a long history of co-optation, acquisition, and the stifling of competition from the major film studios present in Hollywood, all of whom pose a threat to the autonomy that is sought after in these markets by filmmakers and film audiences. -

Good Food ... Good Feelings • Shirley (Neon) — Elisabeth Moss, Logan Lerman, Michael Stuhlbarg

Jay’s Pix Presents at the International improvisational style with a cast of non-actors. Museum — Film historian Jay Duncan and the Fountain Theatre — 2469 Calle de Sunset Film Society host presentations at 2 Guadalupe, 1/2 block south of the plaza in p.m. Saturdays at International Museum of Art, Mesilla. Theatre closed at least through April 3; 1211 Montana (door on Brown opens at 1:30 check website for updates and reopening p.m.). Admission is free. Snacks available for schedule. purchase; guests encouraged to come early for directed and co-written by Billy Wilder. Two Miami — which also happens to be the destina- The historic theater, operated by the Mesilla special attractions. Information: 543-6747 musicians in 1929 Chicago (Jack Lemmon and tion for the mobsters attending a convention. Valley Film Society, features films at 7:30 p.m. (museum), internationalmuseumofart.net and Tony Curtis) accidentally witness the St. • April 18: “Chicago.” The 2002 musical crime nightly, plus 1:30 p.m. Saturday and 2:30 p.m. sunsetfilmsociety.org. Valentine’s Day massacre and go on the lam, comedy-drama film, based on the stage musi- Sunday. Some 7:30 p.m. Sunday night screen- This month’s films Celebrate the Roarin’ 20s. hiding from the mobsters who saw them. Since cal, explores the themes of celebrity, scandal ings have an open caption option. Admission: • April 11 : “Some Like It Hot.” Voted the jobs are scarce during the Great Depression, and corruption in Chicago during the Jazz Age. $8 ($7 matinees, seniors, military and students No. -

2013 Movie Catalog © Warner Bros

1-800-876-5577 www.swank.com Swank Motion Pictures,Inc. Swank Motion 2013 Movie Catalog 2013 Movie © Warner Bros. © 2013 Disney © TriStar Pictures © Warner Bros. © NBC Universal © Columbia Pictures Industries, ©Inc. Summit Entertainment 2013 Movie Catalog Movie 2013 Inc. Pictures, Motion Swank 1-800-876-5577 www.swank.com MOVIES Swank Motion Pictures,Inc. Swank Motion 2013 Movie Catalog 2013 Movie © New Line Cinema © 2013 Disney © Columbia Pictures Industries, Inc. © Warner Bros. © 2013 Disney/Pixar © Summit Entertainment Promote Your movie event! Ask about FREE promotional materials to help make your next movie event a success! 2013 Movie Catalog 2013 Movie Catalog TABLE OF CONTENTS New Releases ......................................................... 1-34 Swank has rights to the largest collection of movies from the top Coming Soon .............................................................35 Hollywood & independent studios. Whether it’s blockbuster movies, All Time Favorites .............................................36-39 action and suspense, comedies or classic films,Swank has them all! Event Calendar .........................................................40 Sat., June 16th - 8:00pm Classics ...................................................................41-42 Disney 2012 © Date Night ........................................................... 43-44 TABLE TENT Sat., June 16th - 8:00pm TM & © Marvel & Subs 1-800-876-5577 | www.swank.com Environmental Films .............................................. 45 FLYER Faith-Based -

Current Film Slate

CURRENT PROJECTS Updated 06 August 2021 For more information on any of the projects listed below, please contact the Premier film team as follows: • Email: [email protected] • Visit our website: https://www.premiercomms.com/specialisms/film/public-relations UK DISTRIBUTION NIGHT OF THE KINGS UK release date: 23 July 2021 (in cinemas) Directed by: Philippe Lacôte Starring: Koné Bakary, Barbe Noire, Steve Tientcheu, Rasmané Ouédraogo, Issaka Sawadogo, Digbeu Jean Cyrille Lass, Abdoul Karim Konaté, Anzian Marcel Laetitia Ky, Denis Lavant Running time: 93 mins Certificate: 12A UK release: 23 July 2021 Premier contacts: Annabel Hutton, Simon Bell, Josh Glenn When a young man (first-timer Koné Bakary) is sent to an infamous prison, located in the middle of the Ivorian forest and ruled by its inmates, he is chosen by the boss 'Blackbeard' (Steve Tientcheu, BAFTA and Academy-Award nominated LES MISÉRABLES) to take part in a storytelling ritual just as a violent battle for control bubbles to the surface. After discovering the grim fate that awaits him at the end of the night, Roman begins to narrate the mystical life of a legendary outlaw to make his story last until dawn and give himself any chance of survival. JOLT UK release date: 23 July 2021 (Amazon Prime Video) Directed by: Tanya Wexler Starring: Kate Beckinsale, Bobby Cannavale, Jai Courtney, Laverne Cox, David Bradley, Ori Pfeffer, Susan Sarandon, Stanley Tucci Running time: 91 mins Certificate: TBC UK release: Amazon Studios Premier contacts: Matty O’Riordan, Monique Reid, Brodie Walker, Priyanka Gundecha Lindy is a beautiful, sardonically-funny woman with a painful secret: Due to a lifelong, rare neurological disorder, she experiences sporadic rage-filled, murderous impulses that can only be stopped when she shocks herself with a special electrode device. -

Glenn-Garland-Editor-Credits.Pdf

GLENN GARLAND, ACE Editor Television PROJECT DIRECTOR STUDIO / PRODUCTION CO. WELCOME TO THE BLUMHOUSE: BLACK BOX Emmanuel Osei-Kuffour Amazon / Blumhouse Productions EP: Jay Ellis, Jason Blum, Aaron Bergman PARADISE CITY*** (series) Ash Avildsen Sumerian Films EP: Lorenzo Antonucci PREACHER (season 3) Various AMC / Sony Pictures Television EP: Sam Catlin, Seth Rogen, Evan Goldberg ALTERED CARBON** (series) Various Netflix / Skydance EP: Laeta Kalogridis, James Middleton, Steve Blackman STAN AGAINST EVIL (series) Various IFC / Radical Media EP: Dana Gould, Frank Scherma, Tom Lassally BANSHEE (series) Ole Christian Madsen HBO / Cinemax Magnus Martens EP: Alan Ball THE VAMPIRE DIARIES (series) Various CW / Warner Bros. Television EP: Julie Plec, Kevin Williamson Feature Films PROJECT DIRECTOR STUDIO / PRODUCTION CO. BROKE Carlyle Eubank Wild West Entertainment Prod: Wyatt Russell, Alex Hertzberg, Peter Billingsley THE TURNING Floria Sigismondi Amblin Partners 3 FROM HELL Rob Zombie Lionsgate FAMILY Laura Steinel Sony Pictures / Annapurna Pictures Official Selection: SXSW Film Festival Prod: Kit Giordano, Sue Naegle, Jeremy Garelick SILENCIO Lorena Villarreal 5100 Films / Prod: Beau Genot 31 Rob Zombie Lionsgate / Saban Films Official Selection: Sundance Film Festival Prod: Mike Elliot, Andy Gould THE QUIET ONES John Pogue Lionsgate / Exclusive Media LORDS OF SALEM Rob Zombie Blumhouse / Anchor Bay Entertainment LOVE & HONOR Danny Mooney IFC Films / Red 56 HALLOWEEN 2 Rob Zombie Dimension Films BUNRAKU* Guy Moshe Snoot Entertainment Official -

Valerio Bonelli Editor

VALERIO BONELLI EDITOR FILM & TELEVISION CYRANO Director: Joe Wright Production Company: Working Title Films SANPA: SINS OF THE SAVIOR Director: Cosima Spender Production Company: Netflix THE WOMAN IN THE WINDOW Director: Joe Wright Production Company: Netflix THE BOY WHO HARNESSED THE WIND Director: Chiwetel Ejiofor Production Company: Potboiler Productions & Netflix Nominated, Best Debut Director and Best Supporting Actor, BIFA Awards (2019) Official Selection, Sundance Film Festival (2019) Official Selection, Berlin Film Festival (2019) DARKEST HOUR Director: Joe Wright Production Company: Working Title Films Nominated, Best Picture & Best Actor, Academy Awards (2018) Winner, Best Leading Actor, BAFTA Awards (2018) Official Selection, Toronto Film Festival (2017) BLACK MIRROR: NOSE DIVE Director: Joe Wright Production Company: Netflix Official Selection, Toronto Film Festival (2016) Official Selection, London Film Festival (2016) LUX ARTISTS | 1 FLORENCE FOSTER JENKINS Director: Stephen Frears Production Company: Pathe THE MARTIAN (Co-editor) Director: Ridley Scott Production Company: 20th Century Fox Official Selection, Toronto Film Festival (2015) THE PROGRAM Director: Stephen Frears Production Company: Working Title Films Official Selection, Toronto Film Festival (2015) Official Selection, London Film Festival (2015) PALIO Director: Cosima Spender Production Company: Playmaker Films Winner, Best Documentary Editing, Tribeca Film Festival (2015) Nominated, Best Documentary, BIFA Awards (2015) Nominated, Best Documentary, Tribeca Film -

Our Festival Partners

Our Festival Partners... A Night of Horror, Accolade Competition, AFI Dallas, AFI FEST, AFM, Almost Famous, Angelus Awards, Ann Arbor Film Festival, Appalachian Film Festival, Ashland Independent, Austin Film Festival, Babelgum, Beloit International, Bend Film Festival Big Bear Lake International Film Festival, Big Apple Film Festival, Big Island Film Festival, Big Sky Documentary Film Festival, Black Maria Film Festival, California Independent, California Film & Video Festival, Cine Gear Expo, Cine Las Americas, Cinequest, Coney Island Film Festival, Cucalorus, Crossroads Film Festival, DC Shorts Film Festival, DV Expo, Duke City Shootout, East Lansing Children’s Film Festival, Elevate Film Festival, Estes Park Film Festival, Fantastic Fest, Filmstock, FirstGlance, Flatland Film Festival, Flint Film Festival, Florida ART, Ft. Lauderdale International Film Festival, 48 Hour Film Project, FTX West Expo, Fusion Film Festival, Fylmz, George Lindsey UNA Festival, Hamptons International Film Festival, Haydenfilms, Hardacre Film Fest, HD Expo, HD Fest, Heart of Gold, Heartland, Indie Memphis, IP Schmoozefest, Jackson Hole Film Festival, Jackson Hole Wildlife, Long Island Film Festival, Los Angeles Film Festival, HP Lovecraft Film Festival, Indie Memphis, Indie Short Films, International Family Film Festival, International Horror & Sci-Fi Film Festival, MacWorld, Magnolia Independent, The Method Fest, Miami International Film Festival, Miami Underground Film Festival, Milwaukee International Film Festival, Moondance, NAB, NAB Post+ Production -

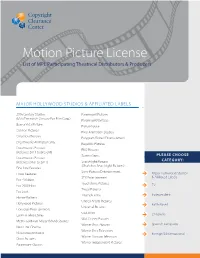

Motion Picture License List of MPL Participating Theatrical Distributors & Producers

Motion Picture License List of MPL Participating Theatrical Distributors & Producers MAJOR HOLLYWOOD STUDIOS & AFFILIATED LABELS 20th Century Studios Paramount Pictures (f/k/a Twentieth Century Fox Film Corp.) Paramount Vantage Buena Vista Pictures Picturehouse Cannon Pictures Pixar Animation Studios Columbia Pictures Polygram Filmed Entertainment Dreamworks Animation SKG Republic Pictures Dreamworks Pictures RKO Pictures (Releases 2011 to present) Screen Gems PLEASE CHOOSE Dreamworks Pictures CATEGORY: (Releases prior to 2011) Searchlight Pictures (f/ka/a Fox Searchlight Pictures) Fine Line Features Sony Pictures Entertainment Focus Features Major Hollywood Studios STX Entertainment & Affiliated Labels Fox - Walden Touchstone Pictures Fox 2000 Films TV Tristar Pictures Fox Look Triumph Films Independent Hanna-Barbera United Artists Pictures Hollywood Pictures Faith-Based Universal Pictures Lionsgate Entertainment USA Films Lorimar Telepictures Children’s Walt Disney Pictures Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer (MGM) Studios Warner Bros. Pictures Spanish Language New Line Cinema Warner Bros. Television Nickelodeon Movies Foreign & International Warner Horizon Television Orion Pictures Warner Independent Pictures Paramount Classics TV 41 Entertaiment LLC Ditial Lifestyle Studios A&E Networks Productions DIY Netowrk Productions Abso Lutely Productions East West Documentaries Ltd Agatha Christie Productions Elle Driver Al Dakheel Inc Emporium Productions Alcon Television Endor Productions All-In-Production Gmbh Fabrik Entertainment Ambi Exclusive Acquisitions -

Movie Inventory - Dvd 8/26/2020 Movie Title Rating

MOVIE INVENTORY - DVD 8/26/2020 MOVIE TITLE RATING 12 STRONG R THE 15:17 PARIS PG-13 1917 R 21 BRIDGES R 47 METERS DOWN PG-13 47 METERS DOWN UNCAGED PG-13 6 DAYS R 7 DAYS IN ENTEBBE PG-13 ABOMINABLE PG ACTS OF VIOLENCE R AD ASTRA PG-13 ADDAMS FAMILY PG ADRIFT PG-13 AFTER PG-13 AFTERMATH R AIR STRIKE R ALADDIN PG ALEX & ME G ALICE THROUGH THE LOOKING GLASS PG ALITA: BATTLE ANGEL PG-13 ALL THE MONEY IN THE WORLD R ALMOST CHRISTMAS PG13 ALPHA PG-13 AMERICAN ANIMALS R AMERICAN ASSASSIN R AMERICAN MADE R AMITYVILLE: THE AWAKENING PG-13 ANGEL HAS FALLEN R THE ANGRY BIRDS MOVIE PG-13 THE ANGRY BIRDS MOVIE 2 PG ANNA R ANNABELLE: COMES HOME R ANNABELLE: CREATION R ANNIHILATION R ANT-MAN PG-13 ANT-MAN: THE WASP PG-13 PAGE 1 of 17 MOVIE INVENTORY - DVD 8/26/2020 MOVIE TITLE RATING AQUAMAN PG-13 ARCTIC PG-13 ARSENAL R THE ART OF RACING IN THE RAIN PG ASSASIN'S CREED PG-13 ASSASSINATION NATION R ATOMIC BLONDE R AVENGERS: AGE OF ULTRON PG-13 AVENGERS: ENDGAME PG-13 AVENGERS: INFINITY WAR PG-13 BAD BOYS FOR LIFE R BAD MOMS R A BAD MOMS CHRISTMAS R BAD SANTA 2 R BAD TIMES AT THE EL ROYALE R BAMBIE G BARBIE & MARIPOSA THE FAIRY PRINCESS UNRATED BARBIE & THE DIAMOND CASTLE UNRATED BARBIE & THE 3 MUSKETEERS UNRATED BARBIE IN A MERMAID TALE 2 UNRATED BARBIE IN PRINCESS POWER UNRATED THE BEACH BUM R BEATRIZ AT DINNER R A BEAUTIFUL DAY IN THE NEIGHBORHOOD PG BEAUTY & THE BEAST PG BEFORE I FALL PG-13 THE BEGUILED R BEIRUT DVD BLU RAY R BEN IS BACK R THE BEST OF ENEMIES PG-13 BLACK AND BLUE R BLACK CHRISTMAS PG-13 BLACK PANTHER PG-13 BLACKkKLANSON R BLADE RUNNER -

I Am Not Your Negro

Magnolia Pictures and Amazon Studios Velvet Film, Inc., Velvet Film, Artémis Productions, Close Up Films In coproduction with ARTE France, Independent Television Service (ITVS) with funding provided by Corporation for Public Broadcasting (CPB), RTS Radio Télévision Suisse, RTBF (Télévision belge), Shelter Prod With the support of Centre National du Cinéma et de l’Image Animée, MEDIA Programme of the European Union, Sundance Institute Documentary Film Program, National Black Programming Consortium (NBPC), Cinereach, PROCIREP – Société des Producteurs, ANGOA, Taxshelter.be, ING, Tax Shelter Incentive of the Federal Government of Belgium, Cinéforom, Loterie Romande Presents I AM NOT YOUR NEGRO A film by Raoul Peck From the writings of James Baldwin Cast: Samuel L. Jackson 93 minutes Winner Best Documentary – Los Angeles Film Critics Association Winner Best Writing - IDA Creative Recognition Award Four Festival Audience Awards – Toronto, Hamptons, Philadelphia, Chicago Two IDA Documentary Awards Nominations – Including Best Feature Five Cinema Eye Honors Award Nominations – Including Outstanding Achievement in Nonfiction Feature Filmmaking and Direction Best Documentary Nomination – Film Independent Spirit Awards Best Documentary Nomination – Gotham Awards Distributor Contact: Press Contact NY/Nat’l: Press Contact LA/Nat’l: Arianne Ayers Ryan Werner Rene Ridinger George Nicholis Emilie Spiegel Shelby Kimlick Magnolia Pictures Cinetic Media MPRM Communications (212) 924-6701 phone [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] 49 west 27th street 7th floor new york, ny 10001 tel 212 924 6701 fax 212 924 6742 www.magpictures.com SYNOPSIS In 1979, James Baldwin wrote a letter to his literary agent describing his next project, Remember This House.