The Presocratic Philosophers

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Special Issue on the Concepts of Contradiction and Unity of Opposites

World Journal of Education and Humanities ISSN 2687-6760 (Print) ISSN 2687-6779 (Online) Vol. 2 No. 2, 2020 www.scholink.org/ojs/index.php/wjeh Special Issue On the Concepts of Contradiction and Unity of Opposites Prof. Zhiyong Dong1* 1 Northwest University, P. R. China * Prof. Zhiyong Dong, Northwest University, P. R. China Received: October 10 18, 2019 Accepted: October 22, 2019 Online Published: October 30, 2019 doi:10.22158/wjeh.v2n2p182 URL: http://dx.doi.org/10.22158/wjeh.v2n2p182 1. Contradiction In Chinese language, the concept of contradiction first refers to the phenomena that people make the two things, which could not be the true things at the same time, as the true things at the same time, that is, to make two opposite and conflict opinions as the correct opinions at the same time. For example, there is a story in ancient China. It is said that a person is selling weapons on the street. He says that his spears could thorn through any thing at one time. Then he says that his shields can keep out any thing at another time. An onlooker asks him what would happen if he use your spear to thrown your shield. Then the person could not answer. (Note 1) This kind of phenomena are called contradiction in formal logic in Chinese language. From this example we can see that it is quite easy to make the phenomena of contradiction in the sense of formal logic, when people make the results of different processes of thinkings as the phenomena and matters to begin a new process of thinking. -

HAVE YOU EVER WONDERED Why Life Comes in Opposites?

2 H AVE YOU EVER WONDERED why life comesin opposites?Why everything you value is one of a pair of opposites? Why all deci- sions are between opposites? Why all desires are based on opposites? Notice that all spatial and directional dimensions are opposites: up vs. down, inside vs. outside, high vs. low, long vs. short, North vs. South, big vs. small, here vs. there, top vs. bottom, left vs. right. And notice that all things we consider serious and important are one pole of a pair of opposites: good vs. evil, life vs. death, pleasure vs. pain, God vs. Satan, freedom vs. bondage. So also, our social and esthetic values are always put in terms of op- posites: successvs. failure, beautiful vs. ugly, strong vs. weak, intelligent vs. stupid. Even our highest abstractions rest on opposites. Logic, for instance, is concerned with the true vs. the false; epistemology, with appearance vs. reality; ontology, with being vs. non-being. Our world seemsto be a massive collection of opposites. This fact is so commonplace as to hardly need mentioning, but the more one ponders it the more it is strikingly peculiar. For nature, it seems, knows nothing of this world of opposites in which people live. Nature doesn't grow true frogs and false frogs, nor moral trees and immoral trees, nor right oceans and wrong oceans. There is no trace in nature of ethical mountains and unethical mountains. Nor are there even such things as beautiful speciesand ugly species-at least not to Nature, for it is pleased to produce all kinds. -

The Wisdom of the Unsayable in the Chinese Tradition Karl-Heinz Pohl

3 The Wisdom of the Unsayable in the Chinese Tradition Karl-Heinz Pohl Concerning Eastern teachings such as Daoism, Buddhism, and Confucianism, there is often widespread confusion about how these are to be classified—as religion or as philosophy. This problem, however, is culturally homemade: the distinction between religion and philosophy based on European cultural tradi- tions often does not apply when we leave our culture behind. Thus, the Eastern teachings, which are often referred to as “wisdom religions” (e.g. by Hans Küng), are either religion and philosophy or neither religion nor philosophy; whichever way you prefer ideologically. As is well known, there is a certain “family resemblance” (as Wittgenstein would put it) between Daoism and Buddhism. There is, however, very little that connects these Asian philosophies and religions with the European tradition emanating from Greco-Roman and Christian thought. This does not mean that their philosophemes would be fundamentally alien to the Europeans: at most they do not belong to the European mainstream. So the family resemblance could certainly be extended to certain European philoso- phers and schools: There is in Europe a tradition—from the pre-Socratics through the apophatic theology and mysticism of the Middle Ages to existen- tialism and philosophy of language of modernity—that has very much in common with Daoism and Buddhism. Hence, a blend of selected passages from Heraclitus (cf. Wohlfart 1998: 24–39), Neo-Pythagoreanism, Sextus Empiricus, Gnosticism, Pseudo-Dionysius the Areopagite, Nicholas of Cusa, Meister Eckhart, Jacob Boehme, Montaigne, Hegel (cf. Wohlfart 1998: 24–39), Heidegger, Wittgenstein, Derrida, et al. -

The Relativity of the Unity of Opposites

RELATIVITY OF THE UNITY OF OPPOSITES 185 essence of the doctrine and would open the door to mech anism, relativism, teleology, and modern neo-Hegelianism. Indeed the mechanists also, as we know, are ready to admit that" all flows, all changes." But" flows and changes" in CHAPTER V their understanding is only a quantitative process, the actual elements remaining unchanged. And the relativist not only admits that " all changes, all flows," but makes THE RELATIVITY OF THE such change absolute, including within it our own know UNITY OF OPPOSITES AND THE ledge. Thus every kind of stability in objective phenomena ABSOLUTENESS OF THEIR is swept away, becoming but a subjective appearance. Our knowledge is held to be limited and distorted in its very CONFLICT nature so that it does not even reflect truly the creative flow ofreality. The teleologically inclined bourgeois thinker also admits IN THE FOR E W 0 R D to the first volume of Capital Marx that" all flows, all changes." But he goes on to affirm wrote: that this flow, this change, is nothing else than the path to " In its rational form dialectic is a scandal and an the realization of ever more perfect forms, the tendency abomination to the bourgeoisie and its doctrinaire spokes towards which is deeply seated in life itself, that movement men because while supplying a positive understanding is determined by those ideal forms in which the imminent of th~ existin~state ofthings, it at the same time furni<;hes purposes of life reside. an understanding of the negation of that state of things, There are other eclectic points of view, as, for instance, and enables us to recognize that that state of things will the theory that history shows an alternation of stable and inevitably break up; it is an abomination to them be revolutionary epochs, the first characterized by definiteness, cause it regards every historically ?evdoped soci~ form stability and self-identity of the processes found in it, the as in fluid movement, as traDSlent; because It lets. -

The Concept of Non-Duality in Śaṅkara and Cusanus

Comparative Philosophy Volume 12, No. 1 (2021): 98-110 Open Access / ISSN 2151-6014 / www.comparativephilosophy.org https://doi.org/10.31979/2151-6014(2021).120109 THE CONCEPT OF NON-DUALITY IN ŚAṄKARA AND CUSANUS JEROME KLOTZ ABSTRACT: When comparing diverse philosophical traditions, it becomes necessary to establish a common point of departure. This paper offers a comparative analysis of Advaita Vedānta Hinduism and esoteric Christianity, as represented by the two highly celebrated figures of Śaṅkara and Nicholas Cusanus, respectively. The common point of departure on which I base this comparison is the concept of “non-duality”—a concept that is fitting for at least two reasons. First, it is general enough to encompass both traditions, pervading the work of each figure, and thus allowing for a kind of “shared language.” Second, it is specific enough to identify a set of core and well-defined principles amenable to systematic study, chief among which are the notions of (1) the “Absolute” as an infinite unity that transcends all determinations (“no-thing”) and exceeds all oppositions (“not-other”), and (2) the world as an ontologically ambiguous “reflection” that simultaneously hides and manifests its meta- ontological Principle. In drawing these connections, I hope to show how the concept of non- duality provides the possibility for a mutual understanding among diverse traditions at the philosophical level. Keywords: Advaita Vedānta, metaphysics, mysticism, Nicholas Cusanus, non-duality, Śaṅkara 1. INTRODUCTION The concept of “non-duality” is not the exclusive possession of any one philosophical system. On the contrary, it can be found—mutatis mutandis—within religio- philosophical traditions the world over: from Philosophical Daoism, Mahāyāna Buddhism, and Advaita Vedānta Hinduism in the East, to Kabbalistic Judaism, esoteric Christianity, and mystical Islam in the West. -

Dewey and the Empirical Unity of Opposites Author(S): James W

Dewey and the Empirical Unity of Opposites Author(s): James W. Garrison Source: Transactions of the Charles S. Peirce Society, Vol. 21, No. 4 (Fall, 1985), pp. 549-561 Published by: Indiana University Press Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/40320113 . Accessed: 28/04/2014 18:57 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at . http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp . JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Indiana University Press is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Transactions of the Charles S. Peirce Society. http://www.jstor.org This content downloaded from 128.95.104.66 on Mon, 28 Apr 2014 18:57:39 PM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions JamesW. Garrison Deweyand the. EmpiricalUnity of Opposites i This paper concentrates on a single paragraph in John Dewey's Experience and Nature, one that introduces an importantand vital principle for the developmentof his thought. Although this principle is well known to Dewey scholars, its full significancehas not always been adequately appreciated. In writingthis paper I hope to establish this theme as crucial to a proper understandingof Dewey's empirically groundednaturalistic metaphysics. II The paragraph in question occurs in the context of Dewey's re- buttal of those philosophies intent on "denying to the universethe characterof contingency. -

紀要19号A(P99-107).Pdf

愛知工業大学研究報告 99 第四号A 昭和59 年 ORIENTAL NOTHINGNESS Kohei Kohei KOKETSU 東洋的無 瀕旗康兵 ln ln this short paper ,1 would like to explain briefty about th 巴 philosophy of Nishida ,Tanabe , Nishitani Nishitani and Hisamatsu. World ," "Goethe's Metaphysical Background" and 1. 1. NISHIDA'S PHILOSOPHY OF ABSOLUTE "The Unity of Opposites." The first of these analyzes the the Mind which contains all reality according to NOTHINGNESS Mahayana though t. The title , "The lntelligible World ,'" refers to the images and concepts present Although Kitaro Nishida (1870 時 1945) is one of ]apan's ]apan's greatest Zen Buddhist philosophers , his idiom within the Mind. According to Nishida , the Mind is and style of thought-organization are difficult for composed of four separate levels ,each supported by West 巴rn readers to follow. the next , in the same way , to use his words , as a fine kimono is lined with silk. From the outermost level to Typical Typical of Mahayana Buddhism is his empha- the innermost ,we have: the Universal of ]udgment , sis sis on the contradictory aspect of phenomeno th 巴 Universal of Self-consciousness , the Universal of logical logical reality ,which is finally "nothingness" or the lntelligible W orld , and then a level called "voidness. "voidness. "ー. Everyone who is familiar with Nothingn 巴ss. One fundamental aspect of Nishida's lndian lndian and Buddhist philosophy knows the philosophy is that being supported by or having a difficulty difficulty of rendering into Western terms and "place" in the Universal of the mind is a necessary concepts concepts those Oriental views which are ascetical prerequisite for the state of "being. -

Henderson Thesis

Apophatic Elements in the Theory and Practice of Psychoanalysis: Pseudo-Dionysius and C.G. Jung by David Henderson Goldsmiths, University of London Submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy 1 I declare that the work in this thesis is my own. David Henderson Date: 2 Acknowledgements I am grateful for the help I have received from my supervisors over the time I have been working on this project: Robert Burns believed in the value of the original proposal and accompanied me in my exploration of the work of Dionysius and neoplatonism. Brendan Callaghan supported me when I was in the doldrums and was wondering whether I would reach port. Roderick Main gave me encouragement to finish. He read my work intelligently and sympathetically. I regret that I did not have the opportunity to discuss my research with him at an earlier stage. This work is dedicated to Susan. 3 Abstract This thesis identifies apophatic elements in the theory and practice of psychoanalysis through an examination of Pseudo-Dionysius and C.G. Jung. Pseudo-Dionysius brought together Greek and Biblical currents of negative theology and the via negativa. The apophatic concepts and metaphors which appear in the work of Pseudo-Dionysius are identified. The psychology of Jung can be read as a continuation and extension of the apophatic tradition. The presence of neoplatonic themes in Jung’s work is discussed, as well as his references to Pseudo-Dionysius. There is a thorough examination of Jung’s discussion of opposites, including his reception of Nicholas of Cusa’s concept of the coincidence of opposites. -

Pre-Socratic Philosophy: Beginning Phase PHIL301 Prof. Oakes Winthrop University Updated: 8/29/12 3:13 PM

Pre-Socratic Philosophy: Beginning Phase PHIL301 Prof. Oakes Winthrop University updated: 8/29/12 3:13 PM From their precursors - As we have seen, the Pre-Socratics appeared against a backdrop of anthropomorphic supernaturalism. o Hesiod’s Theogony provides an expression of this kind of view. - This is not to say that such a worldview is either nonsensical or useless; nor is it without similarity in its general form to the thought of the Pre-Socratics. o There are conceptual affinities giving Hesiod’s account some logical sense. o Even if technically ineffectual, a pervasive anthropomorphism results in a familiarized and therefore less frightening world experience. o And although anthropomorphic and therefore almost certainly false, some explanation is offered for the origin, nature, and behavior of the world. Recall, for example, the early appearance of Eros as a proto- philosophical principle of change. A new genius - It is striking that little precedes the Pre-Socratics that anticipates their revolution. o Although the early Greek world was far from isolated geographically, there is little evidence to suggest that nearby cultures could have provided the primary impetus away from Hesiod’s worldview. o The Babylonians brought astronomy to the Greeks. o The Egyptians had developed mathematics and commerce. o But nowhere else do we see the thorough-going naturalism and rationalism that evolves in Greece. - Several sources of the development of philosophy may be identified. o First, there is the competitive nature of the Greeks, evident in their many agonies, competitions in art, song, dance, theater, and physical prowess. The dialectical method may be construed as a competition in which truth is the prize. -

"THIS SELF IS BRAHMAN": WHITMAN in the LIGHT of TKE UPANISHADS Nand I Ta Nau Ti Yal Mcgill University, Montreal Septem

"THIS SELF IS BRAHMAN": WHITMAN IN THE LIGHT OF TKE UPANISHADS Nand i ta Nau ti yal McGill University, Montreal September . 1996 A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of Graduate Studies and Research in partial fulfilment of the requirements of the degree of Master of Arts Nandita Nautiyal 1996 National Library Bibliothèque nationale du Canada Acquisitions and Acquisitions et Bibliographie Services services bibliographiques 395 Wellington Street 395. nie Wellington OnawaON K1A ON4 ON KIA ON4 canada Canada The author has granted a non- L'auteur a accordé une licence non exclusive licence allowing the exclusive permettant à la National Library of Canada to Bibliothèque nationale du Canada de reproduce, loan, distribute or sell reproduire, prêter, distribuer ou copies of this thesis in microform, vendre des copies de cette thèse sous paper or electronic formats. la forme de microfiche/fjlm, de reproduction sur papier ou sur format électronique. The author retains ownership of the L'auteur conserve la propriété du copyright in ths thesis. Neither the droit d'auteur qui protège cette thèse. thesis nor substantid extracts fkom it Ni la thèse ni des extraits substantiels may be p~tedor otherwise de celle-ci ne doivent être imprimés reproduced without the author's ou autrement reproduits sans son permission. autorisation. TABLE OF CONTENTS TabIe of Contents Abstract Résumé Acknowledgements Chapter One Introduction Chapter Two East or West? Chapter Three Four Stances of the "Self" in Whitman's Poetry and States of Consciousness in the Upanishads Chapter Four Sorne Features of Upanishadic "SelF and ParalleIs with Whitman Chapter Five Contradiction in Whitman and the Upanishads Chapter Six Conclusions No tes Bibliography ABSTRACT This thesis examines the reasons why Walt Whitman has been a "puzzle" to literary critics for well over a century. -

The Unity of Opposites: a Dialectical Principle Author(S): V

S&S Quarterly, Inc. Guilford Press The Unity of Opposites: A Dialectical Principle Author(s): V. J. McGill and W. T. Parry Source: Science & Society, Vol. 12, No. 4 (Fall, 1948), pp. 418-444 Published by: Guilford Press Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/40399913 . Accessed: 28/04/2014 18:44 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at . http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp . JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. S&S Quarterly, Inc. and Guilford Press are collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Science &Society. http://www.jstor.org This content downloaded from 128.95.104.66 on Mon, 28 Apr 2014 18:44:38 PM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions THE UNITY OF OPPOSITES: A DIALECTICAL PRINCIPLE v. j. MCGiLLand w. t. parry INTRODUCTION the unityof opposites and otherdialectical prin- ciples have sufferedvarious "refutations," and certaininter- ALTHOUGHL prêtât ions and misapplicationshave quite properlybeen laid to rest,dialectic is verymuch alive today. The Platonic-Aris- toteliantradition continues, and both the Hegelian and the Marxian dialectichave manyfollowers. The unityof opposites,which Lenin describedas the mostimportant of the dialecticalprinciples,1 states thata thingis determinedby its internaloppositions. The principlewas firstput forwardby the Milesian philosophers of the sixthcentury B.C., and by theircotemporary, Heraclitus of Ephesus.It held its own throughcenturies of philosophicalthought, though it took differentforms which were seldom clearly distin- guished. -

Ce9b670111dea10c25d6d18d5c

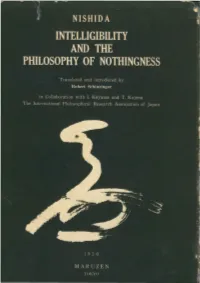

The English speaking phi losophers will welcome the trans lation of the" Intelligible World", by Kitaro Nishida, who is un animously considered as the most distinguished and representative thinker in modern Japan. I have personally been able to ascertain his powerful influence on the philosophical life III various Japanese Universities. Whoever is interested III the general interplay of ideas throughout the world will be anxious to find out how an origi nal philosopher in the Far East reacts to western dialectical thinking and contrives to adapt it to asiatic mentality. Gabriel MARCEL de l'Institut The character if the jacket, pronounce Mu, means Nothingness, and was written by Nishida himself. KITARO NISHIDA Intelligibility and the Philosophy of Nothingness Three Philosophical Essays Translated and introduced by Robert Schinzinger in Collaboration with I. Koyama and T . Kojima The International Philosophical Research AS'sociation of Japan 1958 MARUZEN CO. LTD. TOKYO © 1958 COPYRIGHT BY MARUZEN CO. LTD. PRINTED IN JAPAN CONTENTS INTRODUCTION 1 The Difficulties of Understanding 1 2 The Historical Background of Modern Japanese Philosophy 7 3 Nishida as The Representative Philosopher of Modern Japan 21 4 Being and Nothingness 29 Introduction to "The Intelligible World" 5 Art and Metaphysics 40 Introduction to "Goethe's Metaphysical Background" 6 Philosophy of History 49 Introduction to "The Unity of Opposites" I THE INTELLIGIBLE WORLD 69 II GOETHE'S METAPHYSICAL BACKGROUND 145 III THE UNITY OF OPPOSITES 163 GLOSSARY 243 1. THE ·INTELLIGIBLE WORLD content of that which sees itself, becomes normative and becomes an act of realisation of value. That which confronts and opposes our conscious Self as "objective world", transcends our conscious Self, and is nothing else but the content of Something, deep in our conscious Self; this "something" is the "intelligible Self".