Boomtown Attitudes and Perceptions Non-Renewable Energy Extraction Regions

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Made on Merseyside

Made on Merseyside Feature Films: 2010’s: Across the Universe (2006) Little Joe (2019) Beyond Friendship Ip Man 4 (2018) Yesterday (2018) (2005) Tolkien (2017) X (2005) Triple Word Score (2017) Dead Man’s Cards Pulang (2016) (2005) Fated (2004) Film Stars Don’t Die in Liverpool (2016) Alfie (2003) Fantastic Beasts and Where to Find Them Digital (2003) (2015) Millions (2003) Florence Foster Jenkins (2015) The Virgin of Liverpool Genius (2014) (2002) The Boy with a Thorn in His Side (2014) Shooters (2001) Big Society the Musical (2014) Boomtown (2001) 71 (2013) Revenger’s Tragedy Christina Noble (2013) (2001) Fast and Furious 6 John Lennon-In His Life (2012) (2000) Jack Ryan: Shadow Recruit Parole Officer (2000) (2012) The 51st State (2000) Blood (2012) My Kingdom Kelly and Victor (2011) (2000) Captain America: The First Avenger Al’s Lads (2010) (2000) Liam (2000) 2000’s: Route Irish (2009) Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows (2009) Nowhere Fast (2009) Powder (2009) Nowhere Boy (2009) Sherlock Holmes (2008) Salvage (2008) Kicks (2008) Of Time in the City (2008) Act of Grace (2008) Charlie Noads RIP (2007) The Pool (2007) Three and Out (2007) Awaydays (2007) Mr. Bhatti on Holiday (2007) Outlaws (2007) Grow Your Own (2006) Under the Mud (2006) Sparkle (2006) Appuntamento a Liverpool (1987) No Surrender (1986) Letter to Brezhnev (1985) Dreamchild (1985) Yentl (1983) Champion (1983) Chariots of Fire (1981) 1990’s: 1970’s: Goin’ Off Big Time (1999) Yank (1979) Dockers (1999) Gumshoe (1971) Heart (1998) Life for a Life (1998) 1960’s: Everyone -

Section 18.0 – Socio-Economic Impact Assessment Table of Contents

Suncor Energy Inc. Lewis In Situ Project Volume 2 – Environmental Impact Assessment February 2018 SECTION 18.0 – SOCIO-ECONOMIC IMPACT ASSESSMENT TABLE OF CONTENTS PAGE 18.0 SOCIO-ECONOMIC IMPACT ASSESSMENT ...........................................................18 -1 18.1 Introduction .....................................................................................................18 -1 18.2 Study Area ......................................................................................................18 -1 18.2.1 Temporal Boundary ..........................................................................18 -1 18.2.2 Spatial Boundary ..............................................................................18 -1 18.3 Assessment Approach ....................................................................................18 -3 18.3.1 Regulatory Framework .....................................................................18 -3 18.3.2 Socio-economic Issues Identification ................................................18 -3 18.3.3 Valued Socio-Economic Components and Key Indicators ................ 18-3 18.3.4 Assessment Cases ...........................................................................18 -4 18.3.5 Assessment Criteria .........................................................................18 -5 18.3.6 Constraints Planning ........................................................................18 -6 18.4 Methods ..........................................................................................................18 -

Tombstone, Arizona Shippensburg University

Trent Otis © 2011 Applied GIS with Dr. Drzyzga Tombstone, Arizona Shippensburg University Photo © dailyventure.com. Photographer unknown. Tombstone and the Old West The People Wyatt Earp Virgil and Morgan Earp Tombstone established itself as a boomtown after The tragedy that occurred at Tombstone, Arizona involved Wyatt has been most often Virgil and Morgan Earp are the silver was discovered in a local mine in 1877. It quickly characters who were as interesting as the time period. From characterized as a strict, no nonsense brothers of Wyatt. Virgil held various became a prospering community which attracted all lawmen turned silver prospectors, dentists turned gam- person who prefered to settle disputes law enforcement positions throughout walks of life. blers, outlaws and worse, these men all had their stakes in with words rather than confrontation. his life and was appointed as a Deputy the events at Tombstone. Following are short descriptions U.S Marshal before moving to of these men. Wyatt is arguably one of the most Tombstone. Later on, he was The American Old West has captured the minds and inuential individuals in the Old West. appointed as acting marshal for the imaginations of the American people since the West He encoutered some initial hardship in town after the current marshal was became more civilized in the late 1800s to early 1900s. his life when his rst wife died. accidentally slain by one of the Earp In the early 1880s, a specic event occurred that would Eventually, his sutuation improved and antagonists. capture the essence of the old west in one story. -

The New Normal: the Direct and Indirect Impacts of Oil Drilling and Production on the Emergency Management Function in North Dakota

THE NEW NORMAL: THE DIRECT AND INDIRECT IMPACTS OF OIL DRILLING AND PRODUCTION ON THE EMERGENCY MANAGEMENT FUNCTION IN NORTH DAKOTA Image: nd.gov Carol L. Cwiak Noah Avon Colton Kellen Paul C. Mott Olivia M. Niday Katherine M. Schulz James G. Sink Thomas B. Webb, Jr. January 2015 The NDSU team would like to thank and acknowledge the emergency managers and key partners in North Dakota who added to the richness of this report by participating in this study. Although many of the impacts on emergency management can be drawn from a variety of statistics and conclusions that have been covered in other articles and reports addressing general oil impacts, the voices of the those impacted breathed life and humanity into this examination of North Dakota’s new normal. Oil Impacts on the Emergency Management Function in North Dakota 1 January 2015 Table of Contents Acknowledgements .......................................................................................... 1 Executive Summary ........................................................................................ 3 Introduction ...................................................................................................... 5 Methodology ...................................................................................................... 7 Structural Framing of the Report .............................................................. 11 Emergency Management Function ............................................................ 13 Oil Drilling and Production ....................................................................... -

Housing Needs Assessment | Regional Municipality of Wood Buffalo

WOOD BUFFALO HOUSING NEEDS ASSESSMENT Wood Buffalo Regional Report Prepared by: Urban Matters CCC 2nd Floor, 9902 Franklin Avenue Fort McMurray, AB T9H 2K5 P: (780) 430-4041 May 2019 TABLE OF CONTENTS FIGURES ..................................................................................................3 TABLES ....................................................................................................3 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY.............................................................................1 KEY FINDINGS ..........................................................................................6 COMMUNITY HOUSING PROFILE .............................................................8 Demographics .........................................................................................8 Current Population .........................................................................9 Age and Gender Profile ..................................................................9 Ethnic and Cultural Identity ..........................................................10 Households ...........................................................................................11 Household Type ...........................................................................11 Household Tenure ........................................................................12 Economy ...............................................................................................12 Income .........................................................................................12 -

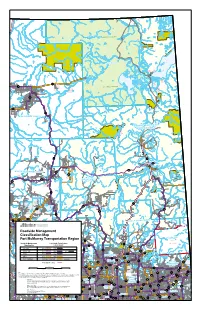

Roadside Management Classification

I.R. I.R. 196A I.R. 196G 196D I.R. 225 I.R. I.R. I.R. 196B 196 196C I.R. 196F I.R. 196E I.R. 223 WOOD BUFFALO NATIONAL PARK I.R. Colin-Cornwall Lakes I.R. 224 Wildland 196H Provincial Park I.R. 196I La Butte Creek Wildland P. Park Ca ribou Mountains Wildland Provincial Park Fidler-Greywillow Wildland P. Park I.R. 222 I.R. 221 I.R. I.R. 219 Fidler-Greywillow 220 Wildland P. Park Fort Chipewyan I.R. 218 58 I.R. 5 I.R. I.R. 207 8 163B 201A I.R . I.R. I.R. 201B 164A I.R. 215 163A I.R. WOOD BU I.R. 164 FFALO NATIONAL PARK 201 I.R Fo . I.R. 162 rt Vermilion 163 I.R. 173B I.R. 201C I.R. I.R. 201D 217 I.R. 201E 697 La Crete Maybelle Wildland P. Park Richardson River 697 Dunes Wildland I.R. P. Park 173A I.R. 201F 88 I.R. 173 87 I.R. 201G I.R. 173C Marguerite River Wildland Provincial Park Birch Mountains Wildland Provincial Park I.R. 174A I.R. I.R. 174B 174C Marguerite River Wildland I.R. Provincial Park 174D Fort MacKay I.R. 174 88 63 I.R. 237 686 Whitemud Falls Wildland FORT Provincial Park McMURRAY 686 Saprae Creek I.R. 226 686 I.R. I.R 686 I.R. 227 I.R. 228 235 Red Earth 175 Cre Grand Rapids ek Wildland Provincial Park Gipsy Lake I.R. Wildland 986 238 986 Cadotte Grand Rapids Provincial Park Lake Wildland Gregoire Lake Little Buffalo Provincial Park P. -

Hoosiers and the American Story Chapter 5

Reuben Wells Locomotive The Reuben Wells Locomotive is a fifty-six ton engine named after the Jeffersonville, Indiana, mechanic who designed it in 1868. This was no ordinary locomotive. It was designed to carry train cars up the steepest rail incline in the country at that time—in Madison, Indi- ana. Before the invention of the Reuben Wells, trains had to rely on horses or a cog system to pull them uphill. The cog system fitted a wheel to the center of the train for traction on steep inclines. You can now see the Reuben Wells at the Children’s Museum of Indianapolis. You can also take rides on historic trains that depart from French Lick and Connersville, Indiana. 114 | Hoosiers and the American Story 2033-12 Hoosiers American Story.indd 114 8/29/14 10:59 AM 5 The Age of Industry Comes to Indiana [The] new kind of young men in business downtown . had one supreme theory: that the perfect beauty and happiness of cities and of human life was to be brought about by more factories. — Booth Tarkington, The Magnificent Ambersons (1918) Life changed rapidly for Hoosiers in the decades New kinds of manufacturing also powered growth. after the Civil War. Old ways withered in the new age Before the Civil War most families made their own of industry. As factories sprang up, hopes rose that food, clothing, soap, and shoes. Blacksmith shops and economic growth would make a better life than that small factories produced a few special items, such as known by the pioneer generations. -

Learning from the Fort Mcmurray Wildland/Urban Interface Fire Disaster

Institute for Catastrophic Institut de prévention Loss Reduction des sinistres catastrophiques Building resilient communities Bâtir des communautés résilientes Why some homes survived: Learning from the Fort McMurray wildland/urban interface fire disaster By Alan Westhaver, M.Sc. March 2017 Why some homes survived: Learning from the Fort McMurray wildland/urban interface fire disaster By Alan Westhaver, M.Sc. March 2017 ICLR research paper series – number 56 Published by Institute for Catastrophic Loss Reduction 20 Richmond Street East, Suite 210 Toronto, Ontario, Canada M5C 2R9 This material may be copied for purposes related to the document as long as the author and copyright holder are recognized. The opinions expressed in this paper are those of the author and not necessarily those of the Institute for Catastrophic Loss Reduction. Nothing in this report is intended to place blame or impart fault for home losses, nor should it be interpreted as doing so. The content of this report is solely to encourage improved preparedness for wildfires in the future by reducing the vulnerability of homes and other structures in the wildland/urban interface to igniting during a wildland fire event. Cover photos: Alan Westhaver ISBN: 978-1-927929-06-3 Copyright©2017 Institute for Catastrophic Loss Reduction ICLR’s mission is to reduce the loss of life and property caused by severe weather and earthquakes through the identification and support of sustained actions that improve society’s capacity to adapt to, anticipate, mitigate, withstand and recover from natural disasters. ICLR is achieving its mission through the development and implementation of its programs Open for business, to increase the disaster resilience of small businesses, Designed for safer living, which increases the disaster resilience of homes, and RSVP cities, to increase the disaster resilience of communities. -

Enbridge 2012 Corporate Social Responsibility Report Social

ENBRIDGE 2012 CORPORATE SOCIAL RESPONSIBILITY REPORT SOCIAL PERFORMANCE ENBRIDGE 2012 CORPORATE SOCIAL RESPONSIBILITY REPORT TABLE OF CONTENTS ABOUT ENBRIDGE .............................................................. 1 LA6 Percentage of total workforce represented in formal joint management-worker health and safety committees that help ABOUT THE ENBRIDGE 2012 CORPORATE SOCIAL monitor and advise on occupational health and safety RESPONSIBILITY REPORT ................................................. 2 programs. ............................................................................... 43 FORWARD-LOOKING INFORMATION ................................ 3 LA7 Rates of injury, occupational diseases, lost days and absenteeism, and number of work-related fatalities by region AWARDS AND RECOGNITION ............................................ 4 and by gender. ....................................................................... 44 STRATEGY AND PROFILE ................................................. 5 LA8 Education, training, counseling, prevention and risk- control programs in place to assist workforce members, their ORGANIZATIONAL PROFILE ............................................ 5 families or community members regarding serious diseases. REPORT PARAMETERS .................................................. 6 ................................................................................................ 44 GOVERNANCE, COMMITMENTS AND ENGAGEMENT ... 12 LA9 Health and safety topics covered in formal agreements with trade unions. .................................................................. -

Impacts of the Proposed Site C Dam on the Hydrologic Recharge of the Peace-Athabasca Delta

Impacts of the Proposed Site C Dam on the Hydrologic Recharge of the Peace-Athabasca Delta Submission to the Site C Joint Review Panel Prepared for: Athabasca Chipewyan First Nation Industry Relations Corporation Fort McMurray, Alberta Mikisew Cree First Nation Government and Industry Relations Fort McMurray, Alberta Prepared by: Martin Carver, PhD, PEng/PGeo, PAg November 25, 2013 Project #501-06 Aqua Environmental Associates Table of Contents Disclaimer ........................................................................................................................................................................... 5 Executive Summary .................................................................................... 6 1.0 Introduction ...................................................................................... 9 1.1 Objectives ....................................................................................................................................................... 9 1.2 Approach and Limitations .............................................................................................................................. 9 2.0 Hydrologic Recharge of a Complex Deltaic System .......................... 11 2.1 Controls on Hydrologic Recharge of the PAD............................................................................................... 11 2.1.1 Recharge Mechanisms and Flood Zones .............................................................................................................. 13 2.1.2 -

2017 Municipal Codes

2017 Municipal Codes Updated December 22, 2017 Municipal Services Branch 17th Floor Commerce Place 10155 - 102 Street Edmonton, Alberta T5J 4L4 Phone: 780-427-2225 Fax: 780-420-1016 E-mail: [email protected] 2017 MUNICIPAL CHANGES STATUS CHANGES: 0315 - The Village of Thorsby became the Town of Thorsby (effective January 1, 2017). NAME CHANGES: 0315- The Town of Thorsby (effective January 1, 2017) from Village of Thorsby. AMALGAMATED: FORMATIONS: DISSOLVED: 0038 –The Village of Botha dissolved and became part of the County of Stettler (effective September 1, 2017). 0352 –The Village of Willingdon dissolved and became part of the County of Two Hills (effective September 1, 2017). CODE NUMBERS RESERVED: 4737 Capital Region Board 0522 Metis Settlements General Council 0524 R.M. of Brittania (Sask.) 0462 Townsite of Redwood Meadows 5284 Calgary Regional Partnership STATUS CODES: 01 Cities (18)* 15 Hamlet & Urban Services Areas (396) 09 Specialized Municipalities (5) 20 Services Commissions (71) 06 Municipal Districts (64) 25 First Nations (52) 02 Towns (108) 26 Indian Reserves (138) 03 Villages (87) 50 Local Government Associations (22) 04 Summer Villages (51) 60 Emergency Districts (12) 07 Improvement Districts (8) 98 Reserved Codes (5) 08 Special Areas (3) 11 Metis Settlements (8) * (Includes Lloydminster) December 22, 2017 Page 1 of 13 CITIES CODE CITIES CODE NO. NO. Airdrie 0003 Brooks 0043 Calgary 0046 Camrose 0048 Chestermere 0356 Cold Lake 0525 Edmonton 0098 Fort Saskatchewan 0117 Grande Prairie 0132 Lacombe 0194 Leduc 0200 Lethbridge 0203 Lloydminster* 0206 Medicine Hat 0217 Red Deer 0262 Spruce Grove 0291 St. Albert 0292 Wetaskiwin 0347 *Alberta only SPECIALIZED MUNICIPALITY CODE SPECIALIZED MUNICIPALITY CODE NO. -

Wyatt Earp and the Gunfight at the OK Corral 1881

Other Forms of Conflict in the West – Wyatt Earp and the Gunfight at the OK Corral 1881 Lesson Objectives: Starter Questions: • To understand how the expansion of 1) Give definitions for the following the West caused other forms of terms/key people to show their tension between settlers, not just conflict between white Americans and relevance to this part of the course Plains Indians. • Pat Garrett: • To explain the significance of the • Vigilante Gunfight at the OK Corral in • Homesteader understanding other types of conflict. • Rancher • To assess the significance of Wyatt • Prospecting Earp and what his story tells us about • Rustling law and order. • Lincoln County As homesteaders, hunters, miners and cattle ranchers flooded onto the Plains, they not only came into conflict with the Plains Indians who already lived there, but also with each other. This was a time of robberies, range wars and Indian wars in the wide open spaces of the West. Gradually, the forces of law and order caught up with the lawbreakers, while the US army defeated the Plains Indians. Other Forms of Conflict in the West – Wyatt Earp and the Gunfight at the OK Corral 1881 Who was Wyatt Earp? What does Wikipedia say?! Wyatt Berry Stapp Earp (March 19, 1848 – January 13, 1929) was an American frontiersman who appears frequently in a variety of well known stories of the American West, especially in notorious "Wild West" towns such as Dodge City, Kansas and Tombstone, Arizona. A hunter, businessman, gambler, and lawman, he worked in a wide variety of trades throughout his life.