Korea: the Mongol Invasions

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Executive Intelligence Review, Volume 22, Number 13, March 24

Join the Schiller Institute! Every renaissance in history has been associated "Whoever would overthrow the liberty of a nation with the written word, from the Greeks, to the must begin by subduing the freeness of speech." Arabs, to the great Italian 'Golden Renaissance.' NeW Federalist is devoted to keeping that "freeness." The Schiller Institute, devoted to creating a new Golden Renaissance from the depths of the current Join the Schiller Institute and receive NEW Dark Age, offers a year's subscription to two prime FEDERALIST and FIDELIO as part of the publications-Fidelio and New Federalist, to new membership: members: • $1,000 Lifetime Membership Fidelio is a quarterly journal of poetry, science and • $500 Sustaining Membership statecraft, which takes its name from Beethoven's • $100 Regular Annual Membership great operatic tribute to freedom and republican All these memberships include: virtue. New Federalist is the national newspaper of the .4 issues FIDELIO ($20 value) American System. As Benjamin Franklin said, .100 issues NEW FEDERALIST ($35 value) ------------------------- clip and send ------------------------- this coupon with your check or money order to: Schiller Institute, Inc. P.o. Box 66082, Washington, D.C. 20035-6082 Sign me up as a member of the Schiller Institute. ___ Name _________________________________ ____ D $1,000 Lifetime Membership o $ 500 Sustaining Membership Address _______________________________________ o $ 100 Regular Annual Membership ___ City _____________________________________ o $ 35 Introductory -

The Writings of Henry Cu

P~per No. 13 The Writings of Henry Cu Kim The Center for Korean Studies was established in 1972 to coordinate and develop the resources for the study of Korea at the University of Hawaii. Its goals are to enhance the quality and performance of Uni versity faculty with interests in Korean studies; develop compre hensive and balanced academic programs relating to Korea; stimulate research and pub lications on Korea; and coordinate the resources of the University with those of the Hawaii community and other institutions, organizations, and individual scholars engaged in the study of Korea. Reflecting the diversity of academic disciplines represented by its affiliated faculty and staff, the Center especially seeks to further interdisciplinary and intercultural studies. The Writings of Henry Cu Killl: Autobiography with Commentaries on Syngman Rhee, Pak Yong-man, and Chong Sun-man Edited and Translated, with an Introduction, by Dae-Sook Suh Paper No. 13 University of Hawaii Press Center for Korean Studies University of Hawaii ©Copyright 1987 by the University of Hawaii Press All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America Honolulu, Hawaii 96822 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Kim, Henry Cu, 1889-1967. The Writings of Henry Cu Kim. (Paper; no. 13) Translated from holographs written in Korean. Includes index. 1. Kim, Henry Cu, 1889-1967. 2. Kim, Henry Cu, 1889-1967-Friends and associates. 3. Rhee, Syngman, 1875-1965. 4. Pak, Yong-man, 1881-1928. 5. Chong, Sun-man. 6. Koreans-Hawaii-Biography. 7. Nationalists -Korea-Biography. I. Suh, Dae-Sook, 1931- . II. Title. III. Series: Paper (University of Hawaii at Manoa. -

The Venetian Conspiracy

The Venetian Conspiracy « Against Oligarchy – Table of Contents Address delivered to the ICLC Conference near Wiesbaden, Germany, Easter Sunday, 1981; (appeared in Campaigner, September, 1981) Periods of history marked, like the one we are living through, by the convulsive instability of human institutions pose a special challenge for those who seek to base their actions on adequate and authentic knowledge of historical process. Such knowledge can come only through viewing history as the lawful interplay of contending conspiracies pitting Platonists against their epistemological and political adversaries. There is no better way to gain insight into such matters than through the study of the history of the Venetian oligarchy, the classic example of oligarchical despotism and evil outside of the Far East. Venice called itself the Serenissima Republica (Serene Republic), but it was no republic in any sense comprehensible to an American, as James Fenimore Cooper points out in the preface to his novel The Bravo. But its sinister institutions do provide an unmatched continuity of the most hideous oligarchical rule for fifteen centuries and more, from the years of the moribund Roman Empire in the West to the Napoleonic Wars, only yesterday in historical terms. Venice can best be thought of as a kind of conveyor belt, transporting the Babylonian contagions of decadent antiquity smack dab into the world of modern states. The more than one and one-half millennia of Venetian continuity is first of all that of the oligarchical families and the government that was their stooge, but it is even more the relentless application of a characteristic method of statecraft and political intelligence. -

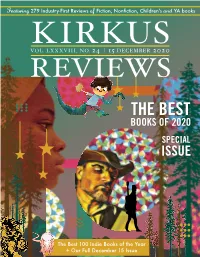

The Best Books of 2020 Special Issue

Featuring 279 Industry-First Reviews of Fiction, Nonfiction, Children'sand YA books VOL.KIRKUS LXXXVIII, NO. 24 | 15 DECEMBER 2020 REVIEWS THE BEST BOOKS OF 2020 SPECIAL ISSUE The Best 100 Indie Books of the Year + Our Full December 15 Issue from the editor’s desk: The Things That Carried Us Through 2020 Chairman HERBERT SIMON President & Publisher BY TOM BEER MARC WINKELMAN # Chief Executive Officer MEG LABORDE KUEHN [email protected] John Paraskevas Are you ready to say goodbye to 2020? I certainly am. Editor-in-Chief TOM BEER While this “annus horribilis”—to borrow a phrase from Queen Elizabeth—has [email protected] Vice President of Marketing been marked by a devastating pandemic, an economic crisis, and a divisive election, SARAH KALINA there have been bright spots. When we could manage to stop doomscrolling and [email protected] Managing/Nonfiction Editor actually focus on reading, the books we spent time with offered respite from the real ERIC LIEBETRAU world—or helped make better sense of it. I was struck, while watching the National [email protected] Fiction Editor Book Awards ceremony last month, when young people’s literature judge Joan Trygg LAURIE MUCHNICK remarked on the “possibly sanity-saving privilege of having a large stack of books to [email protected] Young Readers’ Editor read” and the lively literary discussions that she shared with fellow judges. “When VICKY SMITH I look back on the year 2020, a year I’m sure we’d all like to edit, I’m grateful I will [email protected] Tom Beer Young Readers’ Editor have these memories to keep,” Trygg said. -

Special Issue on Literature No. 4

AWEJ Arab World English Journal INTERNATIONAL PEER REVIEWED JOURNAL ISSN: 2229-9327 جمةل اللغة الانلكزيية يف العامل العريب Special Issue on Literature No. 4 AWEJ October - 2016 www.awej.org Arab World English Journal AWEJ INTERNATIONAL PEER REVIEWED JOURNAL ISSN: 2229-9327 مجلة اللغة اﻻنكليزية في العالم العربي Arab World English Journal (AWEJ) Special Issue on Literature No 4. October, 2016 Team of this issue Guest Editor Dr. John Wallen Department of English Language and Literature University of Sharjah, United Arab Emirates ACKNOWLEDGEMENT I would like to thank all those who contributed to this volume as reviewers of papers. Without their help and dedication, this volume would have not come to the surface. Among those who contributed were the following: Professor Dr. Taher Badinjki Department of English, Faculty of Arts, Al-Zaytoonah University, Amman, Jordan Dr. Hadeer Abo El Nagah Department of English & Translation, College of Humanities Prince Sultan University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia Dr. Gregory Stephens Department of English, University of Puerto Rico-Mayagüez Dr. Dallel SARNOU Department of English studies, Faculty of foreign languages University of Abdelhamid Ibn Badis, Mostaganem, Algeria Prof. Dr. Misbah M.D. Alsulaimaan College of Education and Languages, Lebanese French University, Erbil , Iraq Arab World English Journal www.awej.org ISSN: 2229-9327 Arab World English Journal AWEJ INTERNATIONAL PEER REVIEWED JOURNAL ISSN: 2229-9327 جمةل اللغة الانلكزيية يف العامل العريب Arab World English Journal (AWEJ) Special Issue on Literature -

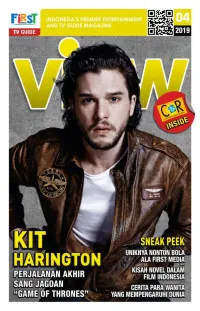

View 201904.Pdf

MY TOP 10 THE WILD CANADIAN YEAR ANIMAL PLANET Film dokumenter tentang satwa liar yang berada di Kanada yang hidup dalam cuaca ekstrim. Dalam MY kondisi tersebut, seorang fotografer mengambil momen penting tentang kehidupan satwa dan cara mereka berinteraksi dengan satwa TOP lainnya, serta bertahan hidup dari kondisi ekstrim. Hal itu menjadikan setiap shoot dari bidikan kamera fotografer begitu berharga. SINGLE PARENTS FOXLIFE Menceritakan beberapa orang tua tunggal yang saling membantu satu sama lain dalam membesarkan anak- anak mereka yang 10FAVORITE berusia 7 tahun. Namun terjadi hubungan pribadi PROGRAMS antara orang tua mereka. LADY CHADalrae’s LOVER ANT-MAN AND THE WASP ONE FOX MOVIES Menceritakan Saat Ant Man tentang tiga wanita berusaha berjuang paruh baya, Cha Jin untuk kembali dengan Ok (Ha Hee Ra), Oh kehidupannya, Dal Sook (Ahn Sun dengan tanggung Young) dan Nam jawabnya sebagai Mi Rae (Go Eun orang tua, dia Mi). Mereka adalah berhadapan kembali teman sekolah dengan Hope menengah yang van Dyne dan Dr. percaya bahwa Hank Pym yang mereka menjalani mendesaknya dengan misi baru. Scott kembali hidup bahagia, tetapi mereka menghadapi bertarung di samping The Wasp. Mereka pun akan krisis dalam hidup mereka. bekerja sama dalam misi baru tersebut. 4 MY TOP 10 HOTEL SOUL GOOD BLOWING UP HISTORY CELESTIAL MOVIES DISCOVERY CHANNEL Katie (Chrissie Mengungkap Chau) adalah rahasia bangunan eksekutif senior bersejarah ataupun di hotel bintang yang menjadi lima. Tetapi suatu landmark di daerah hari, sahabatnya tersebut. Mulai dari mengkhianatinya ukuran, skala, umur, dan mencuri dan lokasi serta pekerjaan serta keajaiban kuno pacarnya. Lebih seperti Piramida buruk lagi, Katie di Mesir hingga terkena pecahan keajaiban modern di Manhattan seperti Empire hujan meteor dan setelah sadar kembali, ia State Building. -

Kirkus-Reviews-Best-Books-Of-2020

Featuring 279 Industry-First Reviews of Fiction, Nonfction, Children's and YA books KIRKUS VOL. LXXXVIII, NO. 24 | 15 DECEMBER 2020 REVIEWS THE BEST BOOKS OF 2020 SPECIAL ISSUE The Best 100 Indie Books of the Year + Our Full December 15 Issue from the editor’s desk: The Things That Carried Us Through 2020 Chairman HERBERT SIMON President & Publisher BY TOM BEER MARC WINKELMAN # Chief Executive Ofcer MEG LABORDE KUEHN [email protected] John Paraskevas Are you ready to say goodbye to 2020? I certainly am. Editor-in-Chief TOM BEER While this “annus horribilis”—to borrow a phrase from Queen Elizabeth—has [email protected] Vice President of Marketing been marked by a devastating pandemic, an economic crisis, and a divisive election, SARAH KALINA there have been bright spots. When we could manage to stop doomscrolling and [email protected] Managing/Nonfction Editor actually focus on reading, the books we spent time with offered respite from the real ERIC LIEBETRAU world—or helped make better sense of it. I was struck, while watching the National [email protected] Fiction Editor Book Awards ceremony last month, when young people’s literature judge Joan Trygg LAURIE MUCHNICK remarked on the “possibly sanity-saving privilege of having a large stack of books to [email protected] Young Readers’ Editor read” and the lively literary discussions that she shared with fellow judges. “When VICKY SMITH I look back on the year 2020, a year I’m sure we’d all like to edit, I’m grateful I will [email protected] To m B e e r Young Readers’ Editor have these memories to keep,” Trygg said. -

Choson Kralliği'ndan Dehan

Hacettepe Üniversitesi Sosyal Bilimler Enstitüsü Tarih Anabilim Dalı CHOSON KRALLIĞI’NDAN DEHAN İMPARATORLUĞU’NA: KORE’NİN DIŞ POLİTİKALARI (1876-1910) Müge Kübra OĞUZ Doktora Tezi Ankara, 2019 CHOSON KRALLIĞI’NDAN DEHAN İMPARATORLUĞU’NA: KORE’NİN DIŞ POLİTİKALARI (1876-1910) Müge Kübra OĞUZ Hacettepe Üniversitesi Sosyal Bilimler Enstitüsü Tarih Anabilim Dalı Doktora Tezi Ankara, 2019 v TEŞEKKÜR Doktora tezi uzun ve yorucu bir süreçte maddi ve manevi olarak yanınıza olan insanlarla ilerleyen kolektif bir çalışmanın ürünüdür. Bu sebeple şükranlarımı borçlu olduğum isim ve kurumları anmadan bu tezi tamamlamam mümkün değildir. Bu uzun süreçte jüri üyeleri Kore araştırmaları konusunda Türkiye’nin önde gelen isimlerinden biri olan Sayın Prof. Dr. M. Ertan GÖKMEN, bilimsel araştırma yöntemlerine ağırlık veren sorularıyla tezi olgunlaştıran Sayın Prof. Dr. Mehmet ÖZDEN’e, değerli vakitlerini ayırarak tezimi okudukları ve yorumlarıyla katkıda bulundukları için Sayın Prof. Dr. Konuralp ERCİLASUN’a, Sayın Doç. Dr. Gürhan KİRİLEN ve her zaman desteğini hissettiğim ve tezimin ortaya çıkmasında büyük emeği olan danışmanım Sayın Doç.Dr. Erkin EKREM’e müteşekkirim. Bu çalışmanın ortaya çıkmasında maddi olarak destek aldığım Türk Tarih Kurumu’na ve Kore’ye gidip araştırmalarımı gerçekleştirmemde ve sahip olduğu zengin kütüphanesiyle araştırmalarımda gerekli kaynaklara ulaşmamda destek olan Güney Kore Büyükelçiliği’ne bağlı Ankara Kore Kültür Merkezi’nin müdürü Güney Kore Ankara Büyükelçiliği Kültür Müsteşarı Sayın Dong Woo CHO ve çalışanlarına teşekkür ederim. Ankara’da Milli Kütüphane’deki Kore Kitaplığı’ndan faydalanabilmem için yardımcı olan çalışanlara ilgilerinden dolayı teşekkür borçluyum. Hacettepe Üniversitesi Kütüphanesi çalışanlarına, ihtiyaç duyduğum kaynakları bildirdiğimde, bu kitapları en kısa süre içerisinde kütüphaneye kazandırdıkları için minnettarım. Korece ile ilgili destek duyduğum her anda yanımda olan Ankara Kral Sejong Enstitüsü’nden değerli hocam Eunmi YU’ya teşekkür ederim. -

$B 7Bt 3B7 \I-J^

UC-NRLF $B 7bT 3b7 h^ \i-j^ :w* .Mr Jj:- .L r ,:/l/. L.yM/r^ia^' c^^^5fe/^v?«?^/^ ^'5^-j:. Vy 4J / ^^1^ ^xV C^-K--^ C-v -^ efritspir6mniturpom$ umnDiiigr Homuuo$rubpnjnftann ^tfimimrm T loniun: 1)1(6 (|i«^«*"^ Diunpiopofimmiwm ife: \ " ^^lafl fflnmowfupoi */ iuouimfrwiimaam >moram(vn(|xttudm RrfiPiiCoimm. 15 anoplDtta iikmilommfxanff y lutmmtisftmtmtmo aus.wrqmmislrnm ctiulhiiUttiJunogRB ^ ImiuwroSPir _ fagroJW ^ bitg fttfontummt o lftnmn (wnwjtfuimriuwaipte np!mn Aimn»wmcm oomminctrimumtpai litstRmmiUumtirmm .•^ *?S CHOICE EXAMPLES OF BOOK ILLUMINATION. Fac-similes from Illuminated Manuscripts and Illustrated Books of Early Date. A PAGE FROM A TOULOUSE BREVIARY. This is a fine example from a breviary with a miniature of St. George, written in Southern France about 1400. It is written on vellum, and is generally considered to represent the perfection of French art. In delicacy and oeauty it is not surpassed by any other illustration in Biblical and liturgical manuscripts. THE v:^^^^.^^^.^.:^..^..^ Copyright, 1901, By the colonial press. SPECIAL INTRODUCTION the most charming poem of Malayan Literature EASILYis the Epic of Bidasari. It has all the absorbing fascination of a fairy tale. We are led into the dreamy atmosphere of haunted palace and beauteous plaisance: we glide in the picturesque imaginings of the oriental poet from the charm of all that is languorously seductive in nature into the shadowy realms of the supernatural. At one moment the sturdy bowman or lithe and agile lancer is before us in hurry- ing column, and at another we are told of mystic sentinels from another world, of Djinns and demons and spirit-princes. All seems shadowy, vague, mysterious, entrancing. -

MNC Play Kembali Siarkan Premier League Pertandingan Klub Favorit Kini Dalam Genggaman

For internal distribution only Let’s Play • 2 memo Chief Executive Ade Tjendra Vera Tanamihardja Editor in Chief Aditya Haikal Managing Editor MAGAZINE Nilasari Yani Dirgahayu Indonesia yang Editor Dina Adriandini ke-72! Octaviniant Aspary Bulan ini, Let’s Play hadir Contributor dengan ulasan spesial Michael Kristanto akan Hari Kemerdekaan Diana Rafikasar Tiara Putri Indonesia yang jatuh pada Devi Setya Lestari tanggal 17 Agustus. Andik Sismanto Untuk menyemarakkan Layout and Design peringatan istimewa Muhammad Ali Mu’awiyah Nasution Yustiawan ini, Let’s Play akan Androgama Jaya Pranata menunjukkan berbagai alasan mengapa Indonesia tidak kalah keren dari negara lainnya dan patut untuk kita puja! Photographer Victor Sasongko Agar semakin mengenal dan mencintai tanah air kita ini, Bayu Aji Saputra Fadil Kalimuda Siregar Let’s Play juga menyajikan ulasan mengenai berbagai program acara kuliner dan traveling khas Indonesia secara eksklusif dari saluran Food & Travel. Tak ketinggalan, wawancara yang inspiratif bersama Runner Up Miss World 2016 asal Indonesia Natasha Publisher Mannuela yang banyak memiliki segudang prestasi untuk mengharumkan nama Indonesia namun tidak berhenti berkarya untuk Indonesia. Ada pula kejutan dari beragam saluran berkualitas MNC Play seperti HBO, CinemaWorld, Zee, TVN, hingga BabyTV Office yang hadir dengan program-program khusus untuk MNC Tower, Lantai 10, 11, 12A, 25, bulan ini. Jl. Kebon Sirih No. 17-19, Gondangdia, Jakarta Pusat Selamat menikmati, Players! Phone : (+62-21) 392 6933 Ext. 1035, Merdeka! Fax : (+62-21) -

Korean Histories

Korean Histories 1.1 2009 INTRODUCTION 2 ChEJU 1901: RECORDS, MEMORIES AND CUrrENT CONCERNS – 3 Boudewijn Walraven KOREA’S FORGOTTEN WAR: APPROPRIATING AND SUBVERTING THE 36 VIETNAM WAR IN KOREAN POPULAR IMAGININGS – Remco E. Breuker ThE FAILINGS OF SUCCESS: THE PROBLEM OF RELIGIOUS MEANING 60 IN MODERN KOREAN HISTORIOGRAPHY – Kenneth Wells HISTORY AS COLONIAL STORYTELLING: YI KWANGSU’S HISTORICAL 81 NOVELS ON FIFTEENTH-CENTURY CHOSON˘ HISTORY – Jung-Shim Lee LiST OF CONTRIBUTORS 106 ISSUING THE FIRST VOLUME OF KOREAN HISTORIES The reasoning behind the creation of this new, biannual peer-reviewed journal, Korean Histories, has proceeded from a simple idea: that the creation of history in the sense of rep- resentations of the past is a social activity that involves many more individuals and groups than the community (or rather communities) of professional historians and, of course, long predates the nineteenth-century appearance of historiography as an academic specialism in the context of the rise of modern nation-states. The involvement of other actors becomes even more obvious if one considers the many ways history actually functions in human societies. Because representations of the past in some form or another are judged to be socially relevant, historical representations are not the exclusive preserve of professional historians; in fact, historical representations are also produced by novelists, film makers, painters, sculptors, journalists, politicians and members of the general public, and are part and parcel of the discourse of many social and political debates. It is probably as difficult to imagine a society that does not in some way represent its past(s) as it is to imagine a society without any form of religion, even if one may doubt the reality of what is represented or of the objects of worship. -

TRACES of a LOST LANDSCAPE TRADITION and CROSS-CULTURAL RELATIONSHIPS BETWEEN KOREA, CHINA and JAPAN in the EARLY JOSEON PERIOD (1392-1550)” By

“TRACES OF A LOST LANDSCAPE TRADITION AND CROSS-CULTURAL RELATIONSHIPS BETWEEN KOREA, CHINA AND JAPAN IN THE EARLY JOSEON PERIOD (1392-1550)” By Copyright 2014 SANGNAM LEE Submitted to the graduate degree program in History of Art and the Graduate Faculty of the University of Kansas in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. ________________________________ Chairperson Marsha Haufler ________________________________ Amy McNair ________________________________ Keith McMahon ________________________________ Maki Kaneko ________________________________ Maya Stiller Date Defended: May 8, 2014 The Dissertation Committee for SANGNAM LEE certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: “TRACES OF A LOST LANDSCAPE TRADITION AND CROSS-CULTURAL RELATIONSHIPS BETWEEN KOREA, CHINA AND JAPAN IN THE EARLY JOSEON PERIOD (1392-1550)” ________________________________ Chairperson Marsha Haufler Date approved: May 8, 2014 ii Abstract This dissertation traces a lost landscape tradition and investigates cross-cultural relationships between Korea, China and Japan during the fifteenth and mid sixteenth centuries. To this end, the main research is given to Landscapes, a set of three hanging scrolls in the Mōri Museum of Art in Yamaguchi prefecture, Japan. Although Landscapes is traditionally attributed to the Chinese master Mi Youren (1075-1151) based on title inscriptions on their painting boxes, the style of the scrolls indicates that the painter was a follow of another Northern Song master, Guo Xi (ca. 1020-ca. 1090). By investigating various aspects of the Mōri scrolls such as the subject matter, style, its possible painter and provenance as well as other cultural aspects that surround the scrolls, this dissertation traces a distinctive but previously unrecognized landscape tradition that existed in early Joseon times.