After the Ball Is Over: Bringing Cinderella Home

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Study Guide for Teachers and Students

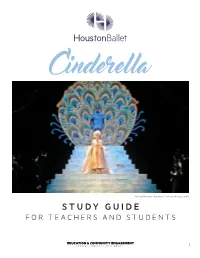

Melody Mennite in Cinderella. Photo by Amitava Sarkar STUDY GUIDE FOR TEACHERS AND STUDENTS 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS PRE AND POST-PERFORMANCE ACTIVITIES AND INFORMATION Learning Outcomes & TEKS 3 Attending a ballet performance 5 The story of Cinderella 7 The Artists who Created Cinderella: Choreographer 11 The Artists who Created Cinderella: Composer 12 The Artists who Created Cinderella Designer 13 Behind the Scenes: “The Step Family” 14 TEKS ADDRESSED Cinderella: Around the World 15 Compare & Contrast 18 Houston Ballet: Where in the World? 19 Look Ma, No Words! Storytelling in Dance 20 Storytelling Without Words Activity 21 Why Do They Wear That?: Dancers’ Clothing 22 Ballet Basics: Positions of the Feet 23 Ballet Basics: Arm Positions 24 Houston Ballet: 1955 to Today 25 Appendix A: Mood Cards 26 Appendix B: Create Your Own Story 27 Appendix C: Set Design 29 Appendix D: Costume Design 30 Appendix E: Glossary 31 2 LEARNING OUTCOMES Students who attend the performance and utilize the study guide will be able to: • Students can describe how ballets tell stories without words; • Compare & contrast the differences between various Cinderella stories; • Describe at least one dance from Cinderella in words or pictures; • Demonstrate appropriate audience behavior. TEKS ADDRESSED §117.106. MUSIC, ELEMENTARY (5) Historical and cultural relevance. The student examines music in relation to history and cultures. §114.22. LANGUAGES OTHER THAN ENGLISH LEVELS I AND II (4) Comparisons. The student develops insight into the nature of language and culture by comparing the student’s own language §110.25. ENGLISH LANGUAGE ARTS AND READING, READING (9) The student reads to increase knowledge of own culture, the culture of others, and the common elements of cultures and culture to another. -

CINDERELLA Curriculum Connections California Content Standards Kindergarten Through Grade 12

San Francisco Operaʼs Rossiniʼs CINDERELLA Curriculum Connections California Content Standards Kindergarten through Grade 12 LANGUAGE ARTS WORD ANALYSIS, FLUENCY, AND VOCABULARY DEVELOPMENT Phonics and Phonemic Awareness: Letter Recognition: Name the letters in a word. Ex. Cinderella = C-i-n-d-e-r-e-l-l-a. Letter/Sound Association: Name the letters and the beginning and ending sound in a word. C-lorind-a Match and list words with the same beginning or ending sounds. Ex. Don Ramiro and Dandini have the same beginning letter “D” and sound /d/; but end with different letters and ending sounds. Additional examples: Don Ramiro, Don Magnifico, Alidoro; Cinderella, Clorinda. Syllables: Count the syllables in a word. Ex.: Cin-der-el-la Match and list words with the same number of syllables. Clap out syllables as beats. Ex.: 1 syllable 2 syllables 3 syllables bass = bass tenor = ten-or soprano = so-pra-no Phoneme Substitution: Play with the beginning sounds to make silly words. What would a “boprano” sound like? (Also substitute middle and ending sounds.) Ex. soprano, boprano, toprano, koprano. Phoneme Counting: How many sounds in a word? Ex. sing = 4 Phoneme Segmentation: Which sounds do you hear in a word? Ex. sing = s/i/n/g. Reading Skills: Build skills using the subtitles on the video and related educator documents. Concepts of Print: Sentence structure, punctuation, directionality. Parts of speech: Noun, verb, adjective, adverb, prepositions. Vocabulary Lists: Ex. Cinderella, Opera glossary, Music and Composition terms Examine contrasting vocabulary. Find words in Cinderella that are unfamiliar and find definitions and roots. Find the definitions of Italian words such as zito, piano, basta, soto voce, etcetera, presto. -

Sweetbox Download

Sweetbox download click here to download Best Sweet box free stock photos download for commercial use in HD high resolution jpg images format. sweet box, free stock photos, sweet box, sweet . sweet box. Download thousands of free photos on Freepik, the finder with more than a million free graphic resources. Best Sweet Box Free Vector Art Downloads from the Vecteezy community. Sweet Box Free Vector Art licensed under creative commons, open source, and. Sweetbox | Sweetbox to stream in hi-fi, or to download in True CD Quality on www.doorway.ru box 10x10cm - Sweet box - Download Free 3D model by Javier Martín Hidalgo ( @www.doorway.ru). Sweetbox Everything's Gonna Be Alright. Closed captioning no. Identifier Sweetbox_Everythings_Gonna_Be_Alright. Scanner Internet Archive. Watch the video, get the download or listen to Sweetbox – Somewhere for free. Somewhere appears on the album Adagio. Discover more music, gig and. Sweet Box Android latest APK Download and Install. Cases Photographers and VideMakers. Each Sweet box icon is a flat icon. All of them are vector icons. They're available for a free download in PNG of up to x px. For vectors, such as SVG, EPS, . Of the million Sweetbox downloads, , were of “Life Is Cool,'” , of “Don't Push Me,” and , of “Cinderella. You can download or listen to the songs of Sweetbox: Miss You, Everything's Gonna Be Alright, Don't Push Me, Everything's Gonna Be Alright (Classic Version ). Download the song of Sweetbox — I Know You're Not Alone, listen to the track, watch clip and find lyrics. A very fresh and modern effect where you make a color change of a COMPLETE BOX of candies. -

Princess Stories Easy Please Note: Many Princess Titles Are Available Under the Call Number Juvenile Easy Disney

Princess Stories Easy Please note: Many princess titles are available under the call number Juvenile Easy Disney. Alsenas, Linas. Princess of 8th St. (Easy Alsenas) A shy little princess, on an outing with her mother, gets a royal treat when she makes a new friend. Andrews, Julie. The Very Fairy Princess Takes the Stage. (Easy Andrews) Even though Gerry is cast as the court jester instead of the crystal princess in her ballet class’s spring performance, she eventually regains her sparkle and once again feels like a fairy princess. Barbie. Barbie: Fairytale Favorites. (Easy Barbie) Barbie: Princess charm school -- Barbie: a fairy secret -- Barbie: a fashion fairytale -- Barbie in a mermaid tale -- Barbie and the three musketeers. Child, Lauren. The Princess and the Pea in Miniature : After the Fairy Tale by Hans Christian Andersen. (Easy Child) Presents a re-telling of the well-known fairy tale of a young girl who feels a pea through twenty mattresses and twenty featherbeds and proves she is a real princess. Coyle, Carmela LaVigna . Do Princesses Really Kiss Frogs? (Easy Coyle) A young girl takes a hike with her father, asking many questions along the way about what princesses do. Cuyler, Margery. Princess Bess Gets Dressed. (Easy Cuyler) A fashionably dressed princess reveals her favorite clothes at the end of a busy day. Disney. 5-Minute Princess Stories. (Easy Disney) Magical tales about princesses from different Walt Disney movies. Disney. Princess Adventure Stories. (Easy Disney) A collection of stories from favorite Disney princesses. Edmonds, Lyra. An African Princess. (Easy Edmonds) Lyra and her parents go to the Caribbean to visit Taunte May, who reminds her that her family tree is full of princesses from Africa and around the world. -

To Whom the Shoe Fits: Cinderella As a Cultural Phenomenon in the Czech and Norwegian Context

Masaryk University Faculty of Arts Department of Germanic, Nordic and Dutch Studies To Whom the Shoe Fits: Cinderella as a Cultural Phenomenon in the Czech and Norwegian Context 2020 Mgr. Adéla Ficová Masaryk University Faculty of Arts Department of Germanic, Nordic and Dutch Studies Norwegian Language and Literature Mgr. Adéla Ficová To Whom the Shoe Fits: Cinderella as a Cultural Phenomenon in the Czech and Norwegian Context M.A. Thesis Supervisor: Mgr. Karolína Stehlíková, Ph.D. 2020 2 Statutory Declaration I hereby declare that I have written the submitted Master Thesis To Whom the Shoe Fits: Cinderella as a Cultural Phenomenon in the Czech and Norwegian Context independently. All the sources used for the purpose of finishing this thesis have been adequately referenced and are listed in the Bibliography. In Brno, 12 May 2020 ....................................... Mgr. Adéla Ficová 3 Acknowledgements I would like to express my sincere gratitude to my supervisor Mgr. Karolína Stehlíková, Ph.D., for her helpful guidance and valuable advices and shared enthusiasm for the topic. I also thank my parents and my friends for their encouragement and support. 4 Table of contents 1 Introduction ..................................................................................................................................... 6 1.1 Literature review ..................................................................................................................... 8 2 Historical genesis of the Cinderella fairy tale ................................................................................ -

Cinderella Wore Combat Boots Audition Monologues

Cinderella Wore Combat Boots Audition Monologues Don’t forget to fill out your audition form and turn it in at auditions! Keep in mind this will be performed in front of a young audience, so we’re looking for interesting characterization and risk taking! Memorization isn’t mandatory but is appreciated. One chair will be provided. You may use your own props. Storyteller and Fairy Godperson are combined roles, but may be split up to allow a larger cast. Those auditioning or being considered for ensemble/understudies will be featured in the ballroom scene, as well as providing animal noises for the Fairy Godperson scene. Storyteller (male or female): Hey! Hello! Today we have the story of Cinderella! Since before people can remember, the Cinderella story has been told in many different languages to each generation. The story begins a long time ago in a far away place a place called a kingdom. In some ways, like the other kingdoms you’ve heard about knights and dragons, peasants and a king to rule over everything but in other ways it was very different. Here we are in the palace and now we are going meet the king himself. Take it way, king! Fairy Godperson (male or female): Cinderella, why are you crying? I’m your Fairy Godperson. I’ll always come to help you if you really need me. You are a very bright, hard working person. You’re a little smudged from work, but you are every bit as attractive as your sisters. Now you are ready to go to the ball. -

Songs by Title

Karaoke Song Book Songs by Title Title Artist Title Artist #1 Nelly 18 And Life Skid Row #1 Crush Garbage 18 'til I Die Adams, Bryan #Dream Lennon, John 18 Yellow Roses Darin, Bobby (doo Wop) That Thing Parody 19 2000 Gorillaz (I Hate) Everything About You Three Days Grace 19 2000 Gorrilaz (I Would Do) Anything For Love Meatloaf 19 Somethin' Mark Wills (If You're Not In It For Love) I'm Outta Here Twain, Shania 19 Somethin' Wills, Mark (I'm Not Your) Steppin' Stone Monkees, The 19 SOMETHING WILLS,MARK (Now & Then) There's A Fool Such As I Presley, Elvis 192000 Gorillaz (Our Love) Don't Throw It All Away Andy Gibb 1969 Stegall, Keith (Sitting On The) Dock Of The Bay Redding, Otis 1979 Smashing Pumpkins (Theme From) The Monkees Monkees, The 1982 Randy Travis (you Drive Me) Crazy Britney Spears 1982 Travis, Randy (Your Love Has Lifted Me) Higher And Higher Coolidge, Rita 1985 BOWLING FOR SOUP 03 Bonnie & Clyde Jay Z & Beyonce 1985 Bowling For Soup 03 Bonnie & Clyde Jay Z & Beyonce Knowles 1985 BOWLING FOR SOUP '03 Bonnie & Clyde Jay Z & Beyonce Knowles 1985 Bowling For Soup 03 Bonnie And Clyde Jay Z & Beyonce 1999 Prince 1 2 3 Estefan, Gloria 1999 Prince & Revolution 1 Thing Amerie 1999 Wilkinsons, The 1, 2, 3, 4, Sumpin' New Coolio 19Th Nervous Breakdown Rolling Stones, The 1,2 STEP CIARA & M. ELLIOTT 2 Become 1 Jewel 10 Days Late Third Eye Blind 2 Become 1 Spice Girls 10 Min Sorry We've Stopped Taking Requests 2 Become 1 Spice Girls, The 10 Min The Karaoke Show Is Over 2 Become One SPICE GIRLS 10 Min Welcome To Karaoke Show 2 Faced Louise 10 Out Of 10 Louchie Lou 2 Find U Jewel 10 Rounds With Jose Cuervo Byrd, Tracy 2 For The Show Trooper 10 Seconds Down Sugar Ray 2 Legit 2 Quit Hammer, M.C. -

Rendering Culturally-Derived Humour in the New Normal

New Voices in Translation Studies 11 (2014) The New Norm(al) in TV comedy: Rendering Culturally-Derived Humour in The New Normal Katerina Perdikaki University of Surrey, UNITED KINGDOM ABSTRACT This paper examines the translation of culturally-derived humour – i.e. humour that is created by means of extralinguistic culture-bound references (ECRs) – in the US- American TV series The New Normal (Adler and Murphy 2013). The data were culled from two episodes that were subtitled into Greek for the purposes of the present study. Both episodes feature a number of instances where assumptions associated with ECRs enhance the intended comic effect. Emphasis is placed on the most indicative examples, where the decision-making process was mainly directed towards facilitating the target audience’s understanding of the humour. The article investigates the identification, description and scholarly analysis of certain subtitling strategies that could contribute to a new model of humour translation in audiovisual texts. The employed strategies interact with factors pertinent to: a) the target audience’s sociocultural familiarity with ECRs and b) elements of characterization within the bounds of the TV programme. KEYWORDS: audiovisual translation, extralinguistic culture-bound references (ECRs), humour, The New Normal, translation strategies. 1. Introduction The aim of this paper is to examine humour translation in the Greek subtitled version of the US-American TV series The New Normal (Adler and Murphy 2013). Contrary to previous research which has mainly focused on verbal aspects of humour in audiovisual translation (Chiaro 1992; Zabalbeascoa 2005), this project aspires to shed light on what can be called culturally-derived humour, i.e. -

Cinderella: Readings

Brian T. Murphy ENG 220-CAH: Mythology and Folklore (Honors) Fall 2019 Cinderella: Readings Eight Variants of “Cinderella”: Charles Perrault, “Cinderella; or, The Little Glass Slipper” ..................................................................1 Catherine-Maire d'Aulnoy, “Finette Cendron” ..................................................................................... 4 Jakob and Wilhelm Grimm, “Ashputtle” .............................................................................................10 Tuan Ch'êng-shih, “Yeh-Hsien (A Chinese 'Cinderella')” ...................................................................12 “The Maiden, the Frog, and the Chief's Son (An African 'Cinderella')” .............................................13 “Oochigeaskw—The Rough-Faced Girl (A Native American 'Cinderella')” ......................................14 Grant, Campbell, adapter. “Walt Disney's 'Cinderella'” ......................................................................15 Sexton, Anne. “Cinderella”..................................................................................................................16 Bettleheim, Bruno. “'Cinderella': A Story of Sibling Rivalry and Oedipal Conflicts” ..............................17 Yolen, Jane. “America's 'Cinderella.'” ......................................................................................................21 Rafferty, Terrence. “The Better to Entertain You With, My Dear.” .........................................................24 www.Brian-T-Murphy.com/Eng220.htm -

Nationalism, the History of Animation Movies, and World War II Propaganda in the United States of America

University of Akureyri Faculty of Humanities and Social Science Modern Studies 2011 Intersections of Modernity: Nationalism, The History of Animation Movies, and World War II propaganda in the United States of America Kristján Birnir Ívansson Final BA Thesis in the Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences University of Akureyri Faculty of Humanities and Social Science Modern studies 2011 Intersections of Modernity: Nationalism, The History of Animation Movies, and World War II propaganda in the United States of America Kristján Birnir Ívansson A final BA Thesis for 180 ECTS unit in the Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences Instructor: Dr. Giorgio Baruchello Statements I hereby declare that I am the only author of this project and that is the result of own research Ég lýsi hér með yfir að ég einn er höfundur þessa verkefnis og að það er ágóði eigin rannsókna ______________________________ Kristján Birnir Ívansson It is hereby confirmed that this thesis fulfil, according to my judgement, requirements for a BA -degree in the Faculty of Hummanities and Social Science Það staðfestist hér með að lokaverkefni þetta fullnægir að mínum dómi kröfum til BA prófs í Hug- og félagsvísindadeild. __________________________ Giorgio Baruchello Abstract Today, animations are generally considered to be a rather innocuous form of entertainment for children. However, this has not always been the case. For example, during World War II, animations were also produced as instruments for political propaganda as well as educational material for adult audiences. In this thesis, the history of the production of animations in the United States of America will be reviewed, especially as the years of World War II are concerned. -

Karaoke Song Book Karaoke Nights Frankfurt’S #1 Karaoke

KARAOKE SONG BOOK KARAOKE NIGHTS FRANKFURT’S #1 KARAOKE SONGS BY TITLE THERE’S NO PARTY LIKE AN WAXY’S PARTY! Want to sing? Simply find a song and give it to our DJ or host! If the song isn’t in the book, just ask we may have it! We do get busy, so we may only be able to take 1 song! Sing, dance and be merry, but please take care of your belongings! Are you celebrating something? Let us know! Enjoying the party? Fancy trying out hosting or KJ (karaoke jockey)? Then speak to a member of our karaoke team. Most importantly grab a drink, be yourself and have fun! Contact [email protected] for any other information... YYOUOU AARERE THETHE GINGIN TOTO MY MY TONICTONIC A I L C S E P - S F - I S S H B I & R C - H S I P D S A - L B IRISH PUB A U - S R G E R S o'reilly's Englische Titel / English Songs 10CC 30H!3 & Ke$ha A Perfect Circle Donna Blah Blah Blah A Stranger Dreadlock Holiday My First Kiss Pet I'm Mandy 311 The Noose I'm Not In Love Beyond The Gray Sky A Tribe Called Quest Rubber Bullets 3Oh!3 & Katy Perry Can I Kick It Things We Do For Love Starstrukk A1 Wall Street Shuffle 3OH!3 & Ke$ha Caught In Middle 1910 Fruitgum Factory My First Kiss Caught In The Middle Simon Says 3T Everytime 1975 Anything Like A Rose Girls 4 Non Blondes Make It Good Robbers What's Up No More Sex.... -

WORDPRESS TRAINING OCTOBER 3, 2018 Tech Transfer Summary WORDPRESS TRAINING | OCTOBER 3, 2018 | Tech Transfer Summary

InTrans WORDPRESS TRAINING OCTOBER 3, 2018 Tech Transfer Summary WORDPRESS TRAINING | OCTOBER 3, 2018 | Tech Transfer Summary Once upon a time, there lived an unhappy young girl. Unhappy fairy, “we’ll need to get you a coach. A real lady would never go she was, for her mother was dead, her father had married an- to a ball on foot!” other woman, a widow with two daughters, and her stepmother “Quick! Get me a pumpkin!” she ordered. didn’t like her one little bit. All the nice things, kind thoughts and loving touches were for her own daughters. And not just “Oh of course,” said Cinderella, rushing away. Then the fairy the kind thoughts and love, but also dresses, shoes, shawls, turned to the cat. delicious food, comfy beds, as well as every home comfort. All this was laid on for her daughters. But, for the poor unhappy “You, bring me seven mice!” girl, there was nothing at all. No dresses, only her stepsisters’ “Seven mice!” said the cat. “I didn’t know fairies ate mice too!” hand-me-downs. No lovely dishes, nothing but scraps. No nice rests and comfort. For she had to work hard all day, and only “They’re not for eating, silly! Do as you are told, and remember when evening came was she allowed to sit for a while by the they must be alive!” fire, near the cinders. That is how she got her nickname, for Cinderella soon returned with a fine pumpkin and the cat with everybody called her Cinderella. Cinderella used to spend long seven mice he had caught in the cellar.