The Mining Parishes of East Buckland and Charles

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Weekend Away Walks

Where we stayed Under canvas at Longlands, a small site in a sheep-grazed valley just outside the coastal village of Combe Martin. Run by Tammy and Jeremy Smith, it has five large safari-style canvas lodges for up to six people, each jutting from the steep hillside. All have sumptuous beds, ensuite loos, wood-fired showers, well- equipped kitchens, a barbecue spot and generous deck. There’s an honesty shop stocked with local goodies, and you can pre-order treats such as breakfast ingredients or fresh sourdough. This is a retreat from heaving high-season beaches, yet a short drive to all the main attractions and close to wild Exmoor Weekend away walks. Looking up to an International Dark Sky Reserve, makes it a great GLAMPING IN RURAL NORTH DEVON HITS THAT place for a bit of stargazing. After a nightcap by the log burner, sinking SWEET SPOT BETWEEN BUZZY HOLIDAY into the king-size bed felt blissful. FAVOURITE AND RELAXING GREEN HAVEN Words: LINDSEY HARRAD any of us inland dwellers have spent the last year fantasising about escaping to the coast for a breath of sea air, a spot of beachcombing and a proper fish-and-chip supper. With so many sharing the same dream of a seaside getaway, the trick is finding somewhere special to stay that’s close to fun things to do, while providing an escape from the hustle and bustle of popular resorts. Balance is achieved, with AND STARS CANOPY Msome ease it seems, between activity and mindfulness on a boutique glamping break in north Devon, where a tranquil hideaway with star-studded skies and spectacular sunsets soothes the spirits after a busy day adventuring. -

Here It Became Obvious That Hollacombe Crediton and Not Hollacombe Winkleigh Was Implied and Quite a Different Proposition

INTRODUCTION In 1876 Charles Worthy wrote “The History of the Manor and Church of Winkleigh”, the first and only book on Winkleigh to be published. Although this valuable little handbook contains many items of interest, not all of which fall within the range of its title, it is not a complete history and consequently fails to meet the requirements of the Devonshire Association. More than a dozen years ago a friend remarked to me that the monks of Crediton at one time used to walk to Hollacombe in order to preach at the ancient chapel of Hollacombe Barton. I was so surprised by this seemingly long trek that I made enquiries of the Devonshire Association. I was referred to the Tower Library of Crediton Church where it became obvious that Hollacombe Crediton and not Hollacombe Winkleigh was implied and quite a different proposition. Meantime the Honorary General Editor of the Parochial Section (Hugh R. Watkins Esq.) suggested that I should write a history of Winkleigh. The undertaking was accepted although it was clear that my only qualification for the task was a deep regard for the associations of the parish combined with a particularly intense love for the hamlet of Hollacombe. The result of this labour of love, produced in scanty spare time, and spread over the intervening years should be considered with these points in view. The proof of this present pudding will be measured by the ease with which the less immediately interesting parts can be assimilated by the general reader. Due care has been taken to verify all the subject matter. -

Georgeham Trail

Georgeham Trail This walk of approximately 7.5 miles (12km) starts from Caen Street Car Park in the centre of Braunton and proceeds around West Hill to Nethercott and North Buckland before turning west to Georgeham; returning in a circular route through Lobb. Passing through open countryside, farmland and villages, some parts of the walk involve country lanes, so beware of traffic. It is a beautiful walk at any time of the year, but is muddy in places year-round, so wear suitable walking boots or wellies. Georgeham Trail Route Map This walk starts and finishes at Caen Street Car Park in the centre of Braunton village. It is located just off the B3231, which leads towards Saunton. Within the car park, Braunton Museum, Braunton Countryside Centre and The Museum of British Surfing can all be found – each are worth a visit before or after your walk. Page 2 Georgeham Trail houses in the vicinity, of similar stature, were at Georgeham Trail Beer Charter, Incledon, Saunton, Lobb, Fairlinch, Ash and Luscott. Most of these houses retain Starting at Caen Street Car Park, leave the car considerable evidence of their ancient status. park by the main exit beside the Museum and cross the main road (Caen Street) to pick up the At the far end of the farm complex, take the left- footpath ahead, which follows the route of the hand (straight on) option, when you reach the 3- old railway line. This in itself is a pleasant walk, way sign. This takes you into Challowell Lane. alongside the River Caen. -

NDAS Newsletter 2

Dates for Your Diary (cont) Saturday 1st July, 1.30pm - 5.00pm: Mining Sunday 17th September, 11.00am - 5.00pm: the Forest: a visit with an Exmoor ranger to Ancient Man on the Moor: a walk with a National remote mineshafts. Meet Ashcombe carpark Park volunteer guide tracing man around Tarr Steps, SS774394. Rough walking; walking boots and the Punchbowl and Caratacus Stone. Meet weatherproof clothing essential. Mounsey Hill Gate SS894319. A 10 mile walk. Booking essential: phone 01398 323841. Walking Sunday 16th July, 12.00pm - 4.00pm: A Walk boots and weatherproof clothing essential. Bring a in the Past: Join a National Park Archaeologist and picnic. a National Trust Warden to look at Iron Age hillforts, a battle site, Victorian mines and an early Other hydro-electric poser plant. Boo king essential, phone 01598 763306. Meet Watersmeet Tea Friday 15th - Sunday 17th September: Society Garden SS744487. Walking boots and for Church Archaeology & Association of Diocesan weatherproof clothing essential. & Cathedral Archaeologists Joint Conference: The Archaeology of Ecclesiastical Landscapes. Exeter Friday 28th July, 10.30am - 5.30pm: (Booking details available on request from Terry Challacombe Cross-Country: A challenging (12 Green: phone 01271 866662) mile) walk on open moorland visiting, among others, Shoulsbury Iron Age fort and Radworthy Saturday 23rd September, 10.00am - medieval settlement. Meet in lay-by opposite 5.15pm: Lundy Studies: a symposium organised by Challacombe Post Office, SS694411. Walking the Lundy Field Society at the Peter Chalk Centre, boots and weatherproof clothing essential. Bring University of Exeter. For information contact David a picnic. and Judy Parker on 01271 865311 or write to Alan Rowland, Mole Cottage, Morwenstow, Cornwall Saturday 5th August, 11.00am: Around the EX32 9JR. -

(Electoral Changes) Order 1999

STATUTORY INSTRUMENTS 1999 No. 2469 LOCAL GOVERNMENT, ENGLAND The District of North Devon (Electoral Changes) Order 1999 Made ---- 6th September 1999 Coming into force in accordance with article 1(2) Whereas the Local Government Commission for England, acting pursuant to section 15(4) of the Local Government Act 1992(a), has submitted to the Secretary of State a report dated January 1999 on its review of the district of North Devon together with its recommendations: And whereas the Secretary of State has decided to give effect, with one modification, to those recommendations: Now, therefore, the Secretary of State, in exercise of the powers conferred on him by sections 17(b) and 26 of the Local Government Act 1992, and of all other powers enabling him in that behalf, hereby makes the following Order: Citation, commencement and interpretation 1.—(1) This Order may be cited as the District of North Devon (Electoral Changes) Order 1999. (2) This Order shall come into force– (a) for the purpose of all proceedings preliminary or relating to any election to be held on 1st May 2003, on 10th October 2002; (b) for all other purposes, on 1st May 2003. (3) In this Order– “the district” means the district of North Devon; “existing”, in relation to a ward, means the ward as it exists on the date this Order is made; any reference to the map is a reference to the map prepared by the Department of the Environment, Transport and the Regions marked “Map of the District of North Devon (Electoral Changes) Order 1999”, and deposited in accordance with regulation 27 of the Local Government Changes for England Regulations 1994(c); and any reference to a number sheet is a reference to the sheet of the map which bears that number. -

Braunton and Wrafton Area Study

Braunton and Wrafton Area Study Core Strategy Evidence October 2011 North Devon and Torridge Core Strategy – Braunton and Wrafton Village Study Contents Page 1. Introduction 4 2. Overview 4 2.4 Population 5 2.5 Income 6 2.6 Benefits 7 2.7 Employment 7 2.8 Unemployment 8 2.9 House Prices 9 2.10 Housing Supply 10 2.11 Deprivation 11 2.12 Health 12 2.13 Primary and Secondary Schools 12 2.14 Environment 13 2.15 Open Space 14 2.16 Heritage 14 2.17 Landscape 14 2.18 Community Facilities 16 2.19 Transport 16 2.20 Tourism 17 2.21 Summary of Issues 18 3. Major Planning Applications 18 4. Size, Land Use and Character 19 5. Constraints 19 5.1 Flooding 19 5.2 Topography 19 5.3 Landscape 19 5.4 Biodiversity 20 6. Relationship to Other Centres 20 7. Community 21 7.1 Braunton Parish Plan 2006 21 7.3 North Devon & Torridge Local Strategic Partnership 23 (January 2010) 8. Vision 23 9. Key Land Uses 23 -1- North Devon and Torridge Core Strategy – Braunton and Wrafton Village Study 9.1 Housing 23 9.2 Employment 24 9.3 Retail 25 9.4 Community Facilities 26 9.5 Physical Infrastructure 27 9.6 Transport 27 10. Potential for Growth 28 10.4 South of A361, Wrafton – Option 1 29 10.5 North of A361, Wrafton – Option 2 29 10.6 East of South Park, Braunton – Option 3 29 10.7 Land at Braunton Down, Braunton – Option 4 30 10.8 Land within the Village – Option 5 30 11. -

Exmoor Farmers Livestock Auctions Ltd

EXMOOR FARMERS LIVESTOCK AUCTIONS LTD. CUTCOMBE MARKET Wheddon Cross, Minehead. TA24 7DT WEDNESDAY 2nd JUNE 2021 120 CATTLE SALE AT 11 am 12 HEIFERS & CALVES/COWS 25 BULLING HEIFERS 1 ABERDEEN ANGUS BULL 65 STEERS AND HEIFERS STRICT SOCIAL DISTANCING. FACE MASKS TO BE WORN ONLY ONE PERSON PER BUSINESS EXMOOR FARMERS LIVESTOCK AUCTIONS LTD. Chartered Surveyors, Valuers, Land and Estate Agents Cutcombe Market, Wheddon Cross, Minehead, Somerset Tel: 01643 841841. Tel: Sale Day Only – 01643 841231 www.exmoorfarmers.co.uk e-mail: [email protected] CONDITIONS OF SALE As exhibited in the Auctioneers Offices. Updated by Livestock Auctioneers' Association November 2017 PLEASE NOTE: TB TEST RULE CHANGES DO NOT AFFECT THE 60 DAYS WITHIN WHICH ANIMALS CAN BE MOVED MULTIPLE TIMES. PARKING Please follow signs as appropriate and park in the field adjacent to the sheep pens, this being for cars and livestock vehicles that are empty. Empty livestock vehicles must arrive clean. SIGNS Please obey all signs as to where you can or cannot go. CLOTHES To enter the penning area, sale ring etc. you must be wearing clean clothes/waterproofs and boots. TERMS Terms of Payment are strictly payment on the day of sale. ARRIVAL OF CATTLE VENDORS PLEASE BRING YOUR CATTLE AS EARLY AS POSSIBLE CLEANSING AND DISINFECTION Vendors please note that it would be of great assistance on a busy day if you would sign a declaration that you will C&D your vehicle when you return home or you may cleanse your vehicle at market if you wish. Purchasers please note: you must have a clean vehicle to take stock away. -

Forenames Surname Relationship Status Marriedfor Gender Age YOB

Forenames Surname Relationship Status MarriedFor Gender Age YOB POB Occupation County Address Parish RegDist Hd No Absalom James YEO Head Married M 35 1876 Okehampton Devon Mason Devonshire White Horse Court Okehampton Devon Esb Missing Okehampton 3 1 Absalom John YEO Son M 5 1906 Okehampton Devon School Devonshire White Horse Court Okehampton Devon Esb Missing Okehampton 3 6 Ada YEO Sister Single F 45 1866 Devon Northam Housekeeper Devonshire Mt Dinham St Davids Exeter Exeter 8 2 Ada YEO Wife Married 17 years F 40 1871 Glamorgan Cardiff Glamorganshire 32 Fairfield Avenue Cardiff Cardiff 14 2 Ada RYDER Servant Widow F 38 1873 Malborough Devon Housemaid Devonshire Welby Tavistock Road Devonport Devonport Devonport 95 5 Ada YEO Wife Married 18 years F 35 1876 London Devonshire 12 Beach Road Hele Ilfracombe Ilfracombe Barnstaple 9 2 Ada YEO Wife Married 6 years F 33 1878 Clovelly Devon Glamorganshire 10 Bishop ST Cardiff Cardiff 15 2 Ada YEO Daughter Married 4 years F 27 1884 Kingston on Thames Surrey 76 Canbury Avenue Kingston‐On Thames Kingston on Thames Kingston 5 4 Ada YEO Daughter Single F 25 1886 London Poplar Clerk Merchant Essex 79 Kingston Road Ilford Ilford Romford 7 4 Ada YEO Daughter Single F 22 1889 London Southwark Sewing Machinist Blouses London 40 Rowfant Road Wandsworth Borough Wandsworth 4 7 Ada DUMMETT Servant Single F 18 1893 Devon Berrynarbor General Servant Domestic Devonshire Wescott Barton Marwood Barnstaple Marwood Barnstaple 740 5 Ada DAVIS Servant Single F 17 1894 Alfreton Derbyshire General Servant Domestic Derbyshire -

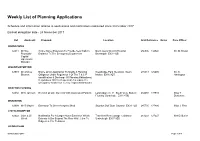

Weekly List of Planning Applications

Weekly List of Planning Applications Schedule and information relating to applications and notifications registered since 30 October 2017 Earliest delegation date - 24 November 2017 Ref Applicant: Proposal: Location Grid Reference Notes Case Officer BARNSTAPLE 64011 Mr Rae Single Storey Extension To Provide New Walk In North Devon District Hospital 256506 134540 Mr. M. Brown Reynolds - Entrance To The Emergency Department Barnstaple EX31 4JB Capital Operations Manager BISHOPS NYMPTON 63973 Mr Andrew Notice Of An Application To Modify A Planning Westbridge Park Newtown South 275843 125605 Mr. S. Blowers Obligation Under Regulation 3 Of The T & C P Molton EX36 3QT Harrington (modification & Discharge Of Planning Obligations) Regulations 1992 In Respect Of Amending The Occupancy Restriction To Key / Agricultural Worker BRATTON FLEMING 64032 Mr K Jackson Erection Of One Dwelling With Associated Parking Land Adjacent 11 South View Bratton 264658 137910 Miss T Fleming Barnstaple EX31 4TQ Blackmore BRAUNTON 63994 Mr R Mayne Extension To Green-keepers Shed Saunton Golf Club Saunton EX33 1LG 245735 137486 Miss J. Pine CHITTLEHAMPTON 64022 John & Jill Notification For A Larger Home Extension Which Travellers Rest Cottage Cobbaton 261233 127227 Mrs D. Butler O'neil Extends 4.00m Beyond The Rear Wall, 3.6m To Umberleigh EX37 9SD Ridge & 2.31m To Eaves GEORGEHAM 06 November 2017 Page 1 of 4 64025 Mr M Notification Of Works To Trees In A Conservation St Georges House Georgeham 246504 139931 42 Days Mr. A. Jones Larrington Area In Respect Of Re-pollarding Of Sycamore Braunton EX33 1JN Notice LB (group A) And Lime (group B), Crown Reduction Of CA Cherry (b), Selective Branch Removal From Sycamore (e) & Recoppicing Of Sycamore (d&e) 64008 Mr & Mrs Erection Of Replacement Dwelling Together With 1 Stoney Cottage Croyde Braunton 243851 139458 Miss S. -

Tabor Hill Heasley Mill, Devon EX36

Tabor Hill Heasley Mill, Devon EX36 A spectacular Exmoor farm in a glorious private setting with an attached annexe and an independent studio, extensive outbuildings including an indoor riding school and 203 acres. Situation & Amenities Tabor Hill is situated within the Exmoor National Park and a short drive from the popular village of North Molton (3 miles), which has excellent amenities including a shop with banking facilities, two pubs, primary school (OFSTED rated 2 Good), parish church and a garage (see www.northmoltonvillage.co.uk). 5 5 4 The neighbouring towns of South Molton and Barnstaple (9.1 miles) both have a selection of shops and other amenities including medical, dental and veterinary surgeries. c. 203 For more extensive shopping, Taunton (36.1 miles) and Acres Exeter (49 miles) are both with a reasonable driving distance. Barnstaple also has a regular rail service to Exeter (1 hour 15 minutes). Tiverton Parkway (31 miles) has a rail service to London Paddington which arrives in just over 2 hours. Exeter Airport (45.9 miles) has connections to several UK and House The Hovel international destinations, including a regular, 1-hour service to London City Airport. There is a wide choice of schools both from the State and independent sectors. These include two village primary schools within a 3-mile radius and a choice of independent schools such as West Buckland (XX miles) and Blundell’s School in Tiverton (25 miles). North Molton 3 miles, A361 5.4 miles, South Molton 6.6 miles, Barnstaple town centre 16.4 miles (Exeter 1 hour 15 minutes), Woolacombe Beach 30 miles, J27 M5 29.2 miles, Exeter Airport 45.9 miles (London City Airport 1 hour) (Distances and times approximate) Tabor Hill Believed to have been built between 250 and 300 years ago, Tabor Hill is a traditional Exmoor farmhouse of rendered local stone with a slate roof. -

DEVONSHIRE. BOO 8C3 Luke Thos.Benj.Io George St.Plymouth Newton William, Newton Poppleford, Perriam Geo

TR.!DES DIRECTORY.] DEVONSHIRE. BOO 8C3 Luke Thos.Benj.Io George st.Plymouth Newton William, Newton Poppleford, Perriam Geo. Hy. 7 Catherinest. Exeter Luke Thos.Hy.42Catherine st.Devonprt Ottery St. Mary PerringA.PlymptonSt.Maurice,Plymptn Luscombe Richard,26 Looest.Piymouth Nex Henry, Welland, Cullompton PerrottChas.106Queenst.NewtonAbbot Luscombe Wm.13 Chapel st.Ea.StonehoiNex William, Uffculme, Cullompton Perry John, 27 Gasking st. Plymouth Lyddon Mrs. Elizh. 125Exeterst.Plymth Nicholls George Hy.East st. Okehampton Perry Jn. P. 41 Summerland st. Exeter Lyddon Geo. Chagford, Newton Abbot Nicholls William, Queen st. Barnstaple PesterJ.Nadder water, Whitestone,Exetr LyddonGeo.jun.Cbagford,NewtonAbbot ~icholsFredk.3Pym st.Morice tn.Dvnprt PP.ters James, Church Stanton, Honiton Lyle Samuel, Lana, Tetcott,Holswortby NormanMrs.C.M.Forest.Heavitree,Extr Phillips Thomas, Aveton Gifford S.O Lyne James, 23 Laira street, Plymouth Norman David, Oakford,BamptonR.S.O Phillips Tbos. 68 & 69 Fleet st. Torquay Lyne Tbos. Petrockstowe,Beaford R.S.O Norman William, Martinhoe,Barnstaple Phillips William, Forest. Kingsbridge McDonald Jas. 15 Neswick st.Plymouth Norrish Robert, Broadhempston, Totnes Phippen Thomas, Castle hill, Axminster McLeod William, Russell st. Sidmouth NorthJas.Bishop'sTeignton, Teignmouth Pickard John, High street, Bideford Mc:MullenDanl. 19St.Maryst.Stonehouse Northam Charles, Cotleigh, Honiton Pike James, Bridestowe R.S.O .Maddock Wm.49Richmond st. Plymouth Northam Charles, Off well Pile E. Otterton, Budleigh Salterton S. 0. :Madge M. 19 Upt.on Church rd. Torquay N orthcote Henry, Lapford, M orchard Pile J. Otter ton, Budleigh Salterton S. 0 1t1adge W. 79 Regent st. Plymouth . Bishop R,S.O Pile WiUiam, Aylesbe!l.re, Exeter J\Jansell Jas. -

Knowstone, South Molton, Devon EX36 4RS

Land near Wadham Cross LOT 1 , Knowstone, South Molton, Devon EX36 4RS A mixed block of grass land and moor with views towards Exmoor Knowstone 1.3 miles - South Molton 7.5 miles A361 2.6 miles • BEST AND FINAL OFFERS TO BE RECEIVED BY 12:00 MIDDAY ON WEDNESDAY 14th JULY. • 32.27 acres (13.06 hectares) • Direct Road Access • Views Towards Exmoor • Natural Water • Additional Land Lot Available Guide Price £125,000 01769 572263 | [email protected] Land near Wadham Cross LOT 1 , Knowstone, South Molton, Devon EX36 4RS SITUATION ADDITIONAL LAND LOT AVAILABLE The land lies in an accessible part of north Devon, near to LOT 2 totals 41.29 acres (16.71 hectares) and includes three Wadham Cross on the B3227 and approximately 1.3 miles grass fields and a small area of moor / rough grazing land north-west of Knowstone towards the south-eastern boundary. The market town of South Molton lies 7.5 miles to the west Two of the grass fields are gently sloping with a north and with the small town of Bampton 9 miles to the east. The A361 west facing aspect and the third field is steeper with a south- (North Devon Link Road) can be accessed within 2.6 miles. facing aspect. The field boundaries are traditional hedge banks, some with mature boundary trees. DESCRIPTION LOT 1 extends to approximately 32.27 acres (13.06 hectares) The rough grazing / moor land totals approximately 4.40 and comprises a productive grass field and an area of moor acres and runs down to a stream on the southern boundary.