Kingston, Ontario

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Aird Gallery Robert Houle

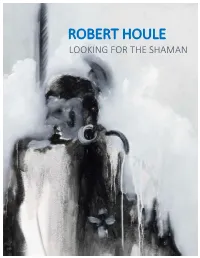

ROBERT HOULE LOOKING FOR THE SHAMAN CONTENTS INTRODUCTION by Carla Garnet ARTIST STATEMENT by Robert Houle ROBERT HOULE SELECTED WORKS A MOVEMENT TOWARDS SHAMAN by Elwood Jimmy INSTALL IMAGES PARTICIPANT BIOS LIST OF WORKS ABOUT THE JOHN B. AIRD GALLERY ROBERT HOULE CURRICULUM VITAE (LONG) PAMPHLET DESIGN BY ERIN STORUS INTRODUCTION BY CARLA GARNET The John B. Aird Gallery will present a reflects the artist's search for the shaman solo survey show of Robert Houle's within. The works included are united by artwork, titled Looking for the Shaman, their eXploration of the power of from June 12 to July 6, 2018. dreaming, a process by which the dreamer becomes familiar with their own Now in his seventh decade, Robert Houle symbolic unconscious terrain. Through is a seminal Canadian artist whose work these works, Houle explores the role that engages deeply with contemporary the shaman plays as healer and discourse, using strategies of interpreter of the spirit world. deconstruction and involving with the politics of recognition and disappearance The narrative of the Looking for the as a form of reframing. As a member of Shaman installation hinges not only upon Saulteaux First Nation, Houle has been an a lifetime of traversing a physical important champion for retaining and geography of streams, rivers, and lakes defining First Nations identity in Canada, that circumnavigate Canada’s northern with work exploring the role his language, coniferous and birch forests, marked by culture, and history play in defining his long, harsh winters and short, mosquito- response to cultural and institutional infested summers, but also upon histories. -

Land Marks Land Marks

Land Marks Land Marks Mary Anne Barkhouse Wendy Coburn Brendan Fernandes Susan Gold Jérôme Havre Thames Art Gallery Art Gallery of Windsor Art Gallery of Peterborough Library and Archives Canada Cataloguing in Publication Land marks : Mary Anne Barkhouse, Wendy Coburn, Brendan Fernandes, Susan Gold and Jérôme Harve. Catalogue for a traveling exhibition held at Thames Art Gallery, June 28 – August 11, 2013; Art Gallery of Windsor, April 20 – June 15, 2014; Art Gallery of Peterborough, January 16 – March 15, 2015. Curator: Andrea Fatona ; co-curator: Katherine Dennis ; essays: Katherine Dennis, Andrea Fatona, Caoimhe Morgan-Feir. Includes bibliographical references. ISBN 978-1-894651-89-9 (pbk.) Contents 1. Identity (Psychology) in art — Exhibitions. 2. Human beings in art — Exhibitions. 3 3. Human ecology in art — Exhibitions. 4. Nature — Effect of human beings on — Exhibitions. Introduction 5. Landscapes in art — Exhibitions. 6. Art, Modern — 21st century — Exhibitions. I. Fatona, Andrea, 1963–, writer of added text II. Morgan-Feir, Caoimhe, writer of added text 7 III. Dennis, Katherine, 1986–, writer of added text IV. Art Gallery of Peterborough, host institution Essay by Andrea Fatona V. Art Gallery of Windsor. host institution VI. Thames Art Gallery, host institution, issuing body 19 N8217.I27L36 2013 704.9’49126 C2013-906537-7 Land Marks Essay by Katherine Dennis 41 Redrawing the Map Essay by Caoimhe Morgan-Feir 50 Artist Biographies 52 List of Works (previous; endsheet) Brendan Fernandes; Love Kill, 2009 (video still) Introduction We are pleased to present Land Marks, an exhibition that features five artists whose works draw our attention to the ways in which humans mark themselves, others, and their environments in order to establish identities, territory, and relationships to the world. -

Grants Listing 2011-2012

2011–2012 GRANTS LISTING LISTE DES SUBVENTIONS OAC CAO 2011–2012 Grants Listing / Liste des subventions 2011-2012 Cover Couverture Dancers from Chi Ping Dance Group perform The Shimmering Water Falls (Sleeves Des danseuses de la troupe Chi Ping, dans The Shimmering Water Falls (Sleeves Dance) at the Asian Heritage Month Gala Performance of Asian Canadian Artists, at Dance), numéro présenté lors de la soirée de gala du Mois du patrimoine asiatique, Hart House in Toronto, May 2012. (Photo: Tam Kam Chiu) à Hart House, à Toronto, en mai 2012. (Photo : Tam Kam Chiu) Contents Sommaire 1 OAC Grants Listing 1 Liste des subventions du CAO 2 Aboriginal Arts 2 Arts autochtones 6 Access and Career Development 6 Accès et évolution professionnelle 8 Anchor Organizations 8 Organismes phares 11 Arts Education 11 Éducation artistique 16 Arts Service Organizations 16 Organismes de service aux arts 19 Community and 19 Arts communautaires Multidisciplinary Arts et multidisciplinaires 24 Compass 24 Compas 27 Dance 27 Danse 31 Franco-Ontarian Arts 31 Arts franco-ontariens 36 Literature 36 Littérature 44 Media Arts 44 Arts médiatiques 48 Music 48 Musique 56 Northern Arts 56 Arts du Nord 59 Ontario-Quebec Artist Residencies 59 Résidences d’artistes Ontario-Québec 61 Theatre 61 Théâtre 67 Touring 67 Tournées 73 Visual Arts and Crafts 73 Arts visuels et métiers d’art 84 Arts Investment Fund 84 Fonds d’investissement dans les arts 93 Awards and Chalmers Program 93 Prix et programme Chalmers 97 Ontario Arts Foundation 97 Fondation des arts de l’Ontario 108 Credits -

Eskimo Sculpture & Prints

1. Possibly 1956 Tarascan Art of Ancient Mexico - Norman Mackenzie Art Gallery Publication: Tarascan Art of Ancient Mexico Clare Herzog The Gallery of Contemporary Art, 1956, 8pp. 2. 15 – 30 October 1961 Eskimo Sculpture & Prints - Norman Mackenzie Art Gallery Note:[Glenbow Foundation/WCAC] 3. 22 June – 27 July 1973 Eskimo Prints and Sculpture - Norman Mackenzie Art Gallery Note:A Community Programme Exhibition Circulation: Publication:Eskimo Prints and Sculpture Paul H. Fudge Norman Mackenzie Art Gallery, 1973, 12 p. 4. 2 – 30 July 1974 The Eskimo Art Collection of the TD Bank - Norman Mackenzie Art Gallery Note:[Toronto Dominion Bank] Circulation: Publication:The Eskimo Art Collection of the Toronto-Dominion Bank Paul Duval Toronto Dominion Bank, 1974, 48 pp. 5. 19 September – 13 October 1975 Saskatchewan Native Painters of the Past - Organized by the Norman Mackenzie Art Gallery Note:A SASKARTIST Series Exhibition/ A Prairie Artist Series Exhibition Developed by Jack Severson, Curatorial Assistant Publication:Saskatchewan Native Artists of the Past no author Norman Mackenzie Art Gallery, 1975, 4 p. ISBN: n\a 6. 17 May – 29 June 1975 The Legacy: Contemporary British Columbia Indian Art - Organized by the British Columbia Provincial Museums Note: [B.C. Provincial Museum] 7. 12 December – 18 January 1975 100 Years of Saskatchewan Indian Art 1830 – 1930 - Organized by the Norman Mackenzie Art Gallery Note:Community Programme Exhibition Circulation: Publication:100 Years of Saskatchewan Indian Art 1830 – 1930 Bob Boyer Norman Mackenzie Art Gallery, 1975, two books 12 p. and one book 16 p. ISBN: 8. 1 June – 9 August 1976 Eskimo Prints and Sculptures - Organized by the Community Programme of the Norman Mackenzie Art Gallery 9. -

Houle November 2013 CV

Robert Houle 1 Education 1975 McGill University, Montreal, Quebec, Bachelor of Education (Art Education) 1972 Salzburg International Summer Academy, Drawing and Painting 1972 University of Manitoba, Winnipeg, Manitoba, Bachelor of Arts (Art History) Selected Solo Exhibitions 2013 Galerie Nicolas Robert, Montreal, Quebec. 2013 1 Bedford Condo Project, Toronto, Ontario 2012 Art Gallery of Windsor, Windsor, Ontario 2012 University of Manitoba School of Art Gallery, Winnipeg, Manitoba 2011 Galerie Nicolas Robert, Montreal, Quebec. 2011 Art Gallery of Peterborough, Peterborough, Ontario 2010 Canadian Cultural Centre, Paris, France 2010 Orenda Art International, Paris, France 2008 Smart Art Project #3, Toronto, Ontario 2007 McMaster Museum of Art, Hamilton, Ontario 2007 McLaughlin Art Gallery, Oshawa, Ontario 2006 Urban Shaman, Winnipeg, Manitoba 2001 MacKenzie Art Gallery, Regina, Saskatchewan 2001 Agnes Etherington Art Centre, Kingston, Ontario 2000 Carleton University Art Gallery, Ottawa, Ontario 2000 Mendel Art Gallery, Saskatoon, Saskatchewan 2000 Museum of Contemporary Canadian Art, Toronto, Ontario 1999 Winnipeg Art Gallery, Winnipeg Manitoba 1996 Garnet Press Gallery, Toronto, Ontario 1994 Garnet Press Gallery, Toronto, Ontario 1993 Carleton University Art Gallery, Carleton University, Ottawa, Ontario 1993 Art Gallery of Ontario, Toronto, Ontario 1992 YYZ, Toronto, Ontario 1992 Articule, Montreal, Quebec 1991 Mackenzie Art Gallery, Regina, Saskatchewan 1991 Hood College, Frederick, Maryland 1991 Glenbow - Alberta Institute, Calgary, -

Inclusivity Or Sovereignty? Native American Arts in the Gallery and the Museum Since 1992

Art Journal The mission of Art Journal, formded in 1941, is to provide a forum for Vol. 76, no. 2 scholarship and visual exploration in the visual arts; to be a unique voice in the Summer 2017 field as a peer-reviewed, professionally mediated forum for the arts; to operate in the spaces between commercial publishing, academic presses, and artist EdItor-in-Chlef Rebecca M. Brown presses; to be pedagogically useful by making links between theoretical issues Reviews Editor Kirsten Swenson and their use in teaching at the college and university levels; to explore rela Web Editor Rebecca K. Uchill tionships among diverse forms of art practice and production, as well as among Editorial Director Joe Hannan art making, art history, visual studies, theory, and criticism; to give voice and Editorial Assistant Gavin VN^ens publication opportunity to artists, art historians, and other writers in the arts; Designer Katy Homans to be responsive to issues of the moment in the arts, both nationally and glob Production Manager Nerissa Dominguez Vales ally; to focus on topics related to twentieth- and twenty-first-century concerns: Director of Publications Betty Leigh Hutcheson to promote dialogue and debate. Editorial Board JuanVicenteAliaga, Tatiana E. Flores, Talinn Grigor, Amelia G. Captions in Art Journal and The Art Bulletin use standardized language Jones, Janet Kraynak.Tirza Latimer (Chair), Derek Conrad Murray to describe image copyright and credit information, in order to clarify the copyright status of all images reproduced as far as possible, for the benefit Art (issn 0004-3249) is published quarterly by Taylor & Francis Group. -

NORVAL MORRISSEAU Life & Work by Carmen Robertson

NORVAL MORRISSEAU Life & Work by Carmen Robertson 1 NORVAL MORRISSEAU Life & Work by Carmen Robertson Contents 03 Biography 17 Key Works 38 Significance & Critical Issues 46 Style & Technique 55 Where to See 61 Notes 68 Glossary 76 Sources & Resources 83 About the Author 84 Copyright & Credits 2 NORVAL MORRISSEAU Life & Work by Carmen Robertson Norval Morrisseau (1931–2007) is considered by many to be the Mishomis, or grandfather, of contemporary Indigenous art in Canada. His life has been sensationalized in newspapers and documentaries while his unique artistic style has pushed the boundaries of visual storytelling. The creator of the Woodland School of art and a prominent member of the Indian Group of Seven, Morrisseau is best known for using bright colours and portraying traditional stories, spiritual themes, and political messages in his work. 3 NORVAL MORRISSEAU Life & Work by Carmen Robertson EARLY YEARS Anishinaabe artist Norval Morrisseau was born in 1931 at a time when Indigenous1 peoples in Canada were confined to reserves, forced to attend residential schools, and banned from practising traditional ceremonial activities.2 He was the oldest of five children born to Grace Theresa Nanakonagos and Abel Morrisseau, and, in keeping with Anishinaabe tradition, he was sent to live with his maternal grandparents at Sand Point reserve on the shores of Lake Nipigon, Ontario. There, Morrisseau learned the stories and cultural traditions of his peoples from his grandfather Moses Potan Nanakonagos, a shaman trained within the Midewiwin spiritual tradition. From his grandmother Veronique Nanakonagos, he learned about Catholicism. A present-day map of Northern Ontario showing the communities where Norval Morrisseau lived. -

Daphne Odjig: Indigenous Art and Contemporary Curatorial Practices

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works School of Arts & Sciences Theses Hunter College Summer 8-5-2020 Daphne Odjig: Indigenous Art and Contemporary Curatorial Practices Lucy Kay Riley CUNY Hunter College How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/hc_sas_etds/643 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] Daphne Odjig: Indigenous Art and Contemporary Cultural Practices by Lucy Kay Riley Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Art History, Hunter College The City University of New York 2020 Thesis Sponsor: July 19, 2020 Dr. Harper Montgomery Date Signature July 21, 2020 Dr. Nebahat Avcıoğlu Date Signature of Second Reader TABLE OF CONTENTS Acknowledgements………………………………………………………………….....……….ii-v List of Illustrations……………………………………………………………….……...…....vi-vii Introduction…………………………………………………………………….……..…….…1-22 Chapter One: Odjig’s Artistic and Activist Development: 1942-1976……………..….….…23-46 Chapter Two: Odjig’s Retrospectives 1985-6 and 2007-10……………………………….…47-66 Chapter Three: The Indian in Transition………………………………..………….…….…..67-85 Conclusion……………………………………………………………………...……….……86-94 Bibliography…………………………………………………………...……….…….………95-98 Appendix………………………………………………………………...………….………99-105 Illustrations…………………………………………………………………….………..…106-126 i ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I would like to first and foremost thank Professors Harper Montgomery and Nebahat Avcıoğlu for their guidance and support for this thesis. Their careful edits and suggestions greatly strengthened my thesis. I have learned so much from them throughout my time at Hunter. There are a number of people in Daphne Odjig’s life who expressed their interest. -

Looking for Stories and Unbroken Threads: Museum Artifacts As Women’S History and Cultural Legacy by Sherry Farrell Racette

Restoring the Balance First Nations Women, Community, and Culture Image Not Available Maria Hupfield,An Indian Act (Moccasins), 1997 Restoring the Balance First Nations Women, Community, and Culture Gail Guthrie Valaskakis, Madeleine Dion Stout, and Eric Guimond, editors University of Manitoba Press University of Manitoba Press Winnipeg, Manitoba Canada R3T 2M5 uofmpress.ca © University of Manitoba Press 2009 Cover and interior design: Relish Design Studio Cover image: Robert Houle, MorningStar. Collection of Indian and Northern Affairs Canada. Photo by Lawrence Cook. Reproduced by permission of Robert Houle. Library and Archives Canada Cataloguing in Publication Restoring the balance : First Nations women, community, and culture / edited by Gail Guthrie Valaskakis, Madeleine Dion Stout, Eric Guimond. Includes bibliographical references. Issued in print and electronic formats. ISBN 978-0-88755-186-4 (bound). ISBN 978-0-88755-709-5 (pbk.) ISBN 978-0-88755-361-5 (PDF) ISBN 978-0-88755-412-4 (epub) 1. Indian women—Canada—Social conditions. 2. Indian women—Canada—History. 3. Women in community development—Canada. I. Valaskakis, Gail Guthrie II. Stout, Madeleine Dion III. Guimond, EricE98. W8R48 2009 305.48’897071 C2008-907736-9 All author royalties are being donated to the National Aboriginal Achievement Awards of Canada. The University of Manitoba Press gratefully acknowledges the financial support for its publication program provided by the Government of Canada through the Canada Book Fund, the Canada Council for the Arts, the Manitoba Department of Culture, Heritage, Tourism, the Manitoba Arts Council, and the Manitoba Book Publishing Tax Credit. Contents ix • Dedication xi • Acknowledgements xiii • Notes on Co-editors xv • Notes on Contributors 1 • Introduction by Gail Guthrie Valaskakis, Madeleine Dion Stout, and, Eric Guimond 11 • Theme 1: Historic Trauma 13 • Trauma to Resilience: Notes on Decolonization by Cynthia C.