An-Education-In-Sport.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Event Winners

Meet History -- NCAA Division I Outdoor Championships Event Winners as of 6/17/2017 4:40:39 PM Men's 100m/100yd Dash 100 Meters 100 Meters 1992 Olapade ADENIKEN SR 22y 292d 10.09 (2.0) +0.09 2017 Christian COLEMAN JR 21y 95.7653 10.04 (-2.1) +0.08 UTEP {3} Austin, Texas Tennessee {6} Eugene, Ore. 1991 Frank FREDERICKS SR 23y 243d 10.03w (5.3) +0.00 2016 Jarrion LAWSON SR 22y 36.7652 10.22 (-2.3) +0.01 BYU Eugene, Ore. Arkansas Eugene, Ore. 1990 Leroy BURRELL SR 23y 102d 9.94w (2.2) +0.25 2015 Andre DE GRASSE JR 20y 215d 9.75w (2.7) +0.13 Houston {4} Durham, N.C. Southern California {8} Eugene, Ore. 1989 Raymond STEWART** SR 24y 78d 9.97w (2.4) +0.12 2014 Trayvon BROMELL FR 18y 339d 9.97 (1.8) +0.05 TCU {2} Provo, Utah Baylor WJR, AJR Eugene, Ore. 1988 Joe DELOACH JR 20y 366d 10.03 (0.4) +0.07 2013 Charles SILMON SR 21y 339d 9.89w (3.2) +0.02 Houston {3} Eugene, Ore. TCU {3} Eugene, Ore. 1987 Raymond STEWART SO 22y 80d 10.14 (0.8) +0.07 2012 Andrew RILEY SR 23y 276d 10.28 (-2.3) +0.00 TCU Baton Rouge, La. Illinois {5} Des Moines, Iowa 1986 Lee MCRAE SO 20y 136d 10.11 (1.4) +0.03 2011 Ngoni MAKUSHA SR 24y 92d 9.89 (1.3) +0.08 Pittsburgh Indianapolis, Ind. Florida State {3} Des Moines, Iowa 1985 Terry SCOTT JR 20y 344d 10.02w (2.9) +0.02 2010 Jeff DEMPS SO 20y 155d 9.96w (2.5) +0.13 Tennessee {3} Austin, Texas Florida {2} Eugene, Ore. -

16Crewealexandraweb26121920

3 Like the way 13 2019 in review promotion feels? A brief round-up of a monumental year in Salford City’s history... HONOURS Eccles & District League Division 2 1955-56, 1959-60 Eccles & District League Division 3 1958-59 Manchester League Division 1 1968-69 Manchester League Premier Division 1974-75, 1975-76, 1976-77, 1978-79 Northern Premier League Division 1 North 2014-15 Northern Premier League Play-Off Winners 2015-16 National League North 2017-18 National League Play-Off Winners 2018-19 Lancashire FA Amateur Cup 1971, 1973, 1975 Manchester FA Challenge Trophy 1975, 1976 Manchester FA Intermediate Cup 1977, 1979 NWCFL Challenge Cup Take your business to the next level with our 2006 award-winning employee wellbeing services CLUB ROLL President Dave Russell Chairman Karen Baird 16. Salford City vs Crewe Alexandra Secretary Andy Giblin Committee Jim Birtwistle, Pete Byram, Ged Carter, Barbara Gaskill, Terry Gaskill, Ian Malone, Frank McCauley, Paul Raven, 07 32 Counselling Advice Online support George Russell, Bill Taylor, Alan Tomlinson, Dave Wilson Groundsmen George Russell, Steve Thomson On The Road The Gaffer Shop Manager Tony Sheldon CSR Co-ordinator Andrew Gordon In this special, Frank McCauley casts Graham Alexander leaves us with his Media Zarah Connolly, Ryan Deane, his mind back over how away trips final notes of the year. Will Moorcroft Photography Charlotte Tattersall, have changed since 2010. Howard Harrison 42 First Team Manager Graham Alexander 25 Assistant Manager Chris Lucketti Visitors Speak to one of our experts today GK Coach Carlo Nash Kit Manager Paul Rushton On This Day Head of Performance Dave Rhodes Find out more about this afternoon’s Physiotherapist Steve Jordan Boxing Day is a constant fixture in the opponents Crewe Alexandra! Club Doctor Dr. -

Etn1964 Vol11 02

:~/~r-' .;__-,'/>~~"":-\-·.__ : f-:"'-, • •... •·. < ;r . •·.. ·• ?~ 'TRACK ' . if SupplementingTRACK & FIELDNEWS twice monthly. rt_v_o_l_. -1-l,-.-N-o-·.-2---------------------A-u_gu_st-27-· ,-1-96_4_________ .......,_____________ --=, __ I Final Olympic Trials Predictions Foreign News by Dick Drake t' The following dope sheet represents the author's predicted ( With assistance from Sven Ivan Johansson) ~;,<:order of finish for all the competitors in the Final Olympic Trials. ESSEN, WEST GERMANY, 100, Obersiebrasse 10.3; 2. Kmck r:·cThe second column indicates best mark this season and the third is enberg 10.3. HT, Beyer (19 years old) 221'½". ( ~he athlete'; place and mark in the Olympic Semi Trials. In some LANDAU, WEST GERMANY, JT, Stumpp 259'3½". Wilke 10.2w. (:;~cases, the athletes were advanced by the Olympic committee, in LEIPZIG, EAST GERMANY, 800, Ulrich 1:48.5. TJ, Thierfel z;;.·.which i.nstances the word "passed" is used. Comments on each ath der 52'7½". ~ ';Jete follow aa well as general comments for each event. , SIENNE, ITALY, 100, Figuerola (Cuba) 10.2. HH, Ottoz 14.1; 2. Mazza 12.1. HJ, Bogliatto 6'91". ¼~~:t~-1· 00 M.ET· ER· DASH SOFIA, BULGARIA, PV, Khlebarov 15'10½"; 2. Butcher (Pol) ("': :Bob Hayes 10. 2 passed He doesn't lose even injured 15'5". DT, Artarski 185'4". Hf, Rut (Pol) 218'1". 400R, Bulgaria r .'.Charles Greene 10 .3 3-10 .2w If healthy, could be there 40.1. ~,t~·.T:rentonJackson 10 11 1-10.lw Powerfulrunner;goodstarter PRAGUE, 1600R, Czechoslovakia 3:07 .2. ;\;Darel Newman 10.2 6t-10.3w Tailed off in national meets DUSSELOORF, 400, Kindger 46.6. -

SATURDAY 31St OCTOBER Buildbase FA Trophy Rushall Olympic (A)

Good evening and a very warm welcome to the players, officials and supporters of Rushall Olympic, we do hope you enjoy your short stay with us before having a safe journey home. Rushall have made a solid start to this season’s campaign suffering only one defeat in their first 7 league games. A competitive club that are always in and around the playoffs, they will be looking to continue that form. Managed by former Barwell players, Liam Macdonald and Nick Green, they will have done their homework on us, so as ever we will be expecting a tough encounter. A well run club from top to bottom and in their second year with an artificial pitch the club is a good role model for non-league football. Both clubs know that this encounter between us will take place again at Rushall on Saturday in the Buildbase FA Trophy, it’s ironic how these consecutive fixtures seem to happen. We finally got our first win against Nuneaton Borough, which has brought a lot of relief to all connected with the club. I’m sure that will bring a lot of confidence, let’s hope we can kick on from here and get back into the mix on the league front. Finally for tonight, I’m pleased to announce that Jason Ashby owner of UK Flooring Direct has agreed to extend his sponsorship for a further 3 years with the club. He has also made a five figure donation to our fundraising effort for our 3G pitch project. If you read this Jason, all of us at Barwell thank you for your commitment once again and wish you, your family and your business all the best for the future. -

RULES and REGULATIONS

THE EVO-STIK LEAGUE SOUTH Season 2018-2019 RULES and REGULATIONS ONE HUNDRED and TWENTY FIFTH SEASON The Southern Football League Limited FOUNDED 1894-5 Incorporated as a company 24th March 1999 Company Registration No. 3740547 Rules & Regulations Handbook 2018 - 2019 One Hundred & Twenty Fifth Season League Office Suite 3B, Eastgate House, 121-131 Eastgate Street Gloucester, GL1 1PX Office Telephone: 01452 525868 Office Facsimile: 01452 358001 Opening hours: 0900 to 1700 (Monday to Friday, except Bank Holidays) Secretary: Jason Mills (2007) Mobile: 07768 750590 (outside office hours) Email: [email protected] Assistant Secretary: Jack Moore (2016) Email: [email protected] Administration Assistant: Jan Simpson (2014) Email: [email protected] Player Registrations Post: Office address Facsimile: 01452 358001 Email: [email protected] Reporting Match Results Text: 07480 533673 Email: [email protected] 3 League Officers PRESIDENT MR K J ALLEN (1979) (1991) (2010) 33 Megson Drive, Lee-on-the-Solent, Hampshire, PO13 8BA Telephone: 02393 116 134 Mobile: 07899 907960 Email: [email protected] CHAIRMAN MR T T BARRATT (2004) (2016) 16 Deacons Way, Hitchin, Hertfordshire, SG5 2UF Telephone: 01462 431124 Mobile: 07836 558727 Email: [email protected] VICE CHAIRMAN MR A J HUGHES (2015) (2017) 4 Brynmorlais Street, Penydarren, Merthyr Tydfil, CF47 9YE Telephone: 01685 359921 Mobile: 07737 022293 Email: [email protected] -

Kingston Small Boats Head

KINGSTON SMALL BOATS HEAD Saturday 22nd November 2008 Division 1 Pos No Club Status Time 1 5 Thames Tradesmens' RC (Thompson) S1.4X 16 10.6 2 3 Quintin BC (Almand) S1.4- 16 12.3 3 22 University of the West of England (Smith) S2.4+ 16 40.9 4 21 Kingston RC (Thompson) S2.4+ 16 44.4 5 16 Hampton School BC (Kafka) S3.4- 16 45.4 6 4 Walbrook RC (Johncox) S1.4- 16 53.4 7 9 St Paul's School BC (Hilton) J.4+ 16 56.0 8 12 Kingston Grammar School Boat Club (Alcock) J16.4- 17 1.7 9 2 University of the West of England (Smith-Willis S1.4X 17 13.4 PENALTY 10 15 DANSKE STUDENTERS ROKLUB (ZDS-NORD E.2X 17 18.7 11 34 Kingston RC (Ellam/Mackinney) S2.2X 17 21.9 12 53 Charterhouse BC (Charterhouse 1) S4.4+ 17 25.2 13 1 Tiffin School RC (Bott) S3.4X 17 25.3 14 33 Imperial College BC (Tietz/Todd) S1.2- 17 26.8 15 17 Kingston RC (Wheeler) S3.4- 17 28.1 16 31 Tyrian Club (Brett/Stallard) S1.2- 17 36.0 17 13 St George's College BC (Capel) J16.4- 17 40.2 18 20 Auriol Kensington RC (Mead Morning) S2.4+ 17 41.4 19 98 Mortlake Anglian & Alpha BC (Garrod) WS3.4X 17 45.9 20 10 Hampton School BC (Budgett) J.4+ 17 50.9 21 32 Thames Tradesmens' RC (Van Wezel/Bulmer) S1.2- 17 53.9 22 14 St Paul's School BC (Cater) J16.4- 17 57.4 23 92 Kingston RC (Dracott/Gomez) S4.2X 17 57.4 24 55 Kingston RC (Hetherington) S4.4+ 18 0.1 PENALTY 25 62 Hertford College BC (Hertford College Boat Cl S4.4+ 18 4.8 26 35 Bradford-Upon-Avon (BOA-CASEY) S2.2X 18 5.6 27 46 St Paul's School BC (Percin-Janda) J15.4X+ 18 7.8 28 19 Cygnet RC (De Groot) S2.4+ 18 14.5 29 79 Imperial College BC (Whittaker) -

The History of the Pan American Games

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses Graduate School 1964 The iH story of the Pan American Games. Curtis Ray Emery Louisiana State University and Agricultural & Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses Recommended Citation Emery, Curtis Ray, "The iH story of the Pan American Games." (1964). LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses. 977. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses/977 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. This dissertation has been 65—3376 microfilmed exactly as received EMERY, Curtis Ray, 1917- THE HISTORY OF THE PAN AMERICAN GAMES. Louisiana State University, Ed.D., 1964 Education, physical University Microfilms, Inc., Ann Arbor, Michigan THE HISTORY OF THE PAN AMERICAN GAMES A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Education m The Department of Health, Physical, and Recreation Education by Curtis Ray Emery B. S. , Kansas State Teachers College, 1947 M. S ., Louisiana State University, 1948 M. Ed. , University of Arkansas, 1962 August, 1964 PLEASE NOTE: Illustrations are not original copy. These pages tend to "curl". Filmed in the best possible way. UNIVERSITY MICROFILMS, INC. ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This study could not have been completed without the close co operation and assistance of many individuals who gave freely of their time. -

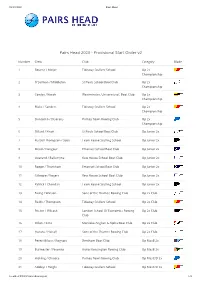

Pairs Head 2020 - Provisional Start Order V2

06/10/2020 Pairs Head Pairs Head 2020 - Provisional Start Order v2 Number Crew Club Category Blade 1 Bourne / Meijer Tideway Scullers School Op 2x Championship 2 O'Sullivan / Middleton St Pauls School Boat Club Op 2x Championship 3 Cowley / Keech Westminster, University of, Boat Club Op 2x Championship 4 Blake / Sanders Tideway Scullers School Op 2x Championship 5 Duncomb / Diserens Putney Town Rowing Club Op 2x Championship 6 Gillard / Kwok St Pauls School Boat Club Op Junior 2x 7 Russell Thompson / Scott Team Keane Sculling School Op Junior 2x 8 Mead / Dangour Emanuel School Boat Club Op Junior 2x 9 Overend / Ballantyne Kew House School Boat Club Op Junior 2x 10 Roope / Thurnham Emanuel School Boat Club Op Junior 2x 11 Gillespie / Rogers Kew House School Boat Club Op Junior 2x 12 Patrick / Chandan Team Keane Sculling School Op Junior 2x 13 Ewing / Watson Sons of the Thames Rowing Club Op 2x Club 14 Fields / Thompson Tideway Scullers School Op 2x Club 15 Fricker / Wilcock London School Of Economics Rowing Op 2x Club Club 16 Dillon / Sims Mortlake Anglian & Alpha Boat Club Op 2x Club 17 Haeata / Halsall Sons of the Thames Rowing Club Op 2x Club 18 Perez-Milans / Rognoni Bentham Boat Club Op MasB 2x 19 Burmester / Fesenko Auriol Kensington Rowing Club Op MasB 2x 20 Hickling / Chiocca Putney Town Rowing Club Op MasC/D 2x 21 Adebiyi / Height Tideway Scullers School Op MasC/D 2x localhost:8000/#/crew-draw-report 1/4 06/10/2020 Pairs Head Number Crew Club Category Blade 22 Blackhurst / Lincoln Sons of the Thames Rowing Club Op MasC/D 2x 23 -

Educating for Professional Life

UOW5_22.6.17_Layout 1 22/06/2017 17:22 Page PRE1 Twenty-five Years of the University of Westminster Educating for Professional Life The History of the University of Westminster Part Five UOW5_22.6.17_Layout 1 22/06/2017 17:22 Page PRE2 © University of Westminster 2017 Published 2017 by University of Westminster, 309 Regent Street, London W1B 2HW. All rights reserved. No part of this pUblication may be reprodUced, stored in any retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, withoUt prior written permission of the copyright holder for which application shoUld be addressed in the first instance to the pUblishers. No liability shall be attached to the aUthor, the copyright holder or the pUblishers for loss or damage of any natUre sUffered as a resUlt of reliance on the reprodUction of any contents of this pUblication or any errors or omissions in its contents. ISBN 978-0-9576124-9-5 A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from The British Library. Designed by Peter Dolton. Design, editorial and production in association with Wayment Print & Publishing Solutions Ltd, Hitchin, Hertfordshire, UK. Printed and bound in the UK by Gomer Press Ltd, Ceredigion, Wales. UOW5_22.6.17_Layout 1 05/07/2017 10:49 Page PRE3 iii Contents Chancellor’s Foreword v Acknowledgements vi Abbreviations vii Institutional name changes ix List of illustrations x 1 Introduction 1 Map showing the University of Westminster’s sites in 1992 8 2 The Polytechnic and the UK HE System pre-1992 -

2010 FISA World Rowing Masters Regatta - St Catharines Order of Racing

2010 FISA World Rowing Masters Regatta - St Catharines Order of Racing Thursday, September 02, 2010 Lane 1 Lane 2 Lane 3 Lane 4 Lane 5 Lane 6 Lane 7 Lane 8 Time Event Description Race Number Prefix Progression Rules Trophy Status 2:30 PM 101 Womens D 4+ Final 1 A Final Only Scheduled WATR COMP (USA) HOOP COMP (INT) ARC COMP (USA) VBC COMP (INT) SSAC COMP (USA) Syracuse Chg (USA) Chester River (USA) (D) (E) 3 (D) (D) 1 (D) (D) (E) 54 56 54 54 53 54 55 Rachel Alexander Stroke Anne Hodkin Stroke A. Dietech Stroke Susan Hingley Stroke Theresa Goman Stroke Lisa Craig Stroke Kate McGraw Stroke Barbara Connolly 3 Els Vandam 3 Beth Gordon 3 Ann Jonik 3 Claudia Schneider 3 Deborah Bradsha 3 Patti Nash 3 Kathrina Schubert 2 Birgith Sims 2 Susie Jones 2 Susan Hooten 2 Caryn Edmonston 2 Kitty English 2 Debbie Yoder 2 Ute Hjobil Bow Zdena Norkova Bow Carolyn Ortwein Bow Helga Kalk-Fedeler Bow Christine Flowers Bow Liz Bates Bow Kendall Ruffatto Bow Mark Mason Cox Victoria Muir Cox Tba Tba Tba Cox Mary Ruddell Cox Mary Rao Cox Joe Peter Cox Shelagh Grasso Cox 2:34 PM 101 Womens D 4+ Final 2 B Final Only Scheduled MC COMP (USA) Carnegie Lake (USA) Rocket City (USA) Cape Cod (USA) Hudson River (USA) St. Catharines (CAN) Lake Union (USA) 1 (D) 2 (D) (D) (D) (D) (D) (D) 51 51 53 52 50 53 52 Katie Cody Stroke Alison Pollini Stroke Elysa Jones Stroke Tina Napolitan Stroke Sarah Herman Stroke Janet Lancaster Stroke Kathleen Roach Stroke Kristine Malcolm 3 Camille Tropp 3 Diane Winters 3 Sheila Morris 3 Susan Beaudry 3 Marion Markarian 3 Ann Wopat 3 Cathy Holdorf 2 Dorene Haney 2 Betsey Bock 2 Mary Eddy 2 Josie Boston 2 Karen Rickers 2 Sara Higgins 2 Cheryl Egan Bow Barbara Hogan Bow Peggy Collins Bow Fran Michaud Bow Catherine Briskey Bow Lorna Hay-Gaudet Bow Dorothy Todd Bow Lesleh Heim Cox Rose Ford Cox Mary Jones Cox Susan Daniels Cox Katherine Boniello Cox Kathy Burtnik Cox Jennifer Gile Cox 2:38 PM 101 Womens D 4+ Final 3 C Final Only Scheduled ARC COMP (USA) Sac State (USA) Don (CAN) Western Res. -

Medicine, Sport and the Body: a Historical Perspective

Carter, Neil. "Science and the Making of the Athletic Body." Medicine, Sport and the Body: A Historical Perspective. London: Bloomsbury Academic, 2012. 81–104. Bloomsbury Collections. Web. 23 Sep. 2021. <http://dx.doi.org/10.5040/9781849662062.ch-004>. Downloaded from Bloomsbury Collections, www.bloomsburycollections.com, 23 September 2021, 13:15 UTC. Copyright © Neil Carter 2012. You may share this work for non-commercial purposes only, provided you give attribution to the copyright holder and the publisher, and provide a link to the Creative Commons licence. 4 Science and the Making of the Athletic Body Introduction At the 1960 Rome Olympics Britain’s Don Thompson won gold in the 50 kilometres walk. Nicknamed Il Topolino (The Little Mouse) by the Italian press, Thompson’s victory was proclaimed heroic and ‘plucky’ in a quintessentially British way. His preparation had been unconventional to say the least. Thompson, who was an insurance clerk, had collapsed in the heat at the Melbourne Games in 1956 and in order to prepare himself for the humidity of Rome he created a steam-room effect in his bathroom using kettles and heaters, and walking up and down continuously on the bathmat. 1 His feat though was set against the growing rivalry in international sport between America and the USSR where greater resources in terms of coaching and sports science were being dedicated to the preparation of their athletes for the Olympic arena. By contrast, Thompson’s preparation refl ected British sport’s amateur tradition. This chapter charts the evolution of athletes’ training methods since the early nineteenth century. -

BRONZO 2016 Usain Bolt

OLIMPIADI L'Albo d'Oro delle Olimpiadi Atletica Leggera UOMINI 100 METRI ANNO ORO - ARGENTO - BRONZO 2016 Usain Bolt (JAM), Justin Gatlin (USA), Andre De Grasse (CAN) 2012 Usain Bolt (JAM), Yohan Blake (JAM), Justin Gatlin (USA) 2008 Usain Bolt (JAM), Richard Thompson (TRI), Walter Dix (USA) 2004 Justin Gatlin (USA), Francis Obikwelu (POR), Maurice Greene (USA) 2000 Maurice Greene (USA), Ato Boldon (TRI), Obadele Thompson (BAR) 1996 Donovan Bailey (CAN), Frank Fredericks (NAM), Ato Boldon (TRI) 1992 Linford Christie (GBR), Frank Fredericks (NAM), Dennis Mitchell (USA) 1988 Carl Lewis (USA), Linford Christie (GBR), Calvin Smith (USA) 1984 Carl Lewis (USA), Sam Graddy (USA), Ben Johnson (CAN) 1980 Allan Wells (GBR), Silvio Leonard (CUB), Petar Petrov (BUL) 1976 Hasely Crawford (TRI), Don Quarrie (JAM), Valery Borzov (URS) 1972 Valery Borzov (URS), Robert Taylor (USA), Lennox Miller (JAM) 1968 James Hines (USA), Lennox Miller (JAM), Charles Greene (USA) 1964 Bob Hayes (USA), Enrique Figuerola (CUB), Harry Jeromé (CAN) 1960 Armin Hary (GER), Dave Sime (USA), Peter Radford (GBR) 1956 Bobby-Joe Morrow (USA), Thane Baker (USA), Hector Hogan (AUS) 1952 Lindy Remigino (USA), Herb McKenley (JAM), Emmanuel McDonald Bailey (GBR) 1948 Harrison Dillard (USA), Norwood Ewell (USA), Lloyd LaBeach (PAN) 1936 Jesse Owens (USA), Ralph Metcalfe (USA), Martinus Osendarp (OLA) 1932 Eddie Tolan (USA), Ralph Metcalfe (USA), Arthur Jonath (GER) 1928 Percy Williams (CAN), Jack London (GBR), Georg Lammers (GER) 1924 Harold Abrahams (GBR), Jackson Scholz (USA), Arthur