Medicine, Sport and the Body: a Historical Perspective

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Oxford V Cambridge Varsity Sports

Fixtures 2013 Changing Times 1 The format of the Achilles Annual Report went largely un‐ ACHILLES CLUB changed from 1920 unl the 1960’s (and if any one can Saturday 16th February ‐ Varsity Field Events & Relays ‐ Lee Valley unearth the lost Reports of 1921‐23 we would be thrilled!). 23‐24th February ‐ BUCS Indoors ‐ Sheffield EIS It was then a small A5 booklet, containing a couple of pages ANNUAL REPORT Saturday 9th March – CUAC Dinner describing the Club’s acvies during the year, the results of the Varsity Match and other compeons, and a compre‐ 13th‐23rd March—OUAC Warm Weather Training ‐ Portugal hensive list of members and their addresses. 24th‐31st March ‐ CUAC Warm Weather Training‐ Malta 3rd‐19th April ‐ Oxford & Cambridge US Tour 6th April ‐ Oxford & Cambridge v Penn & Cornell ‐ Cornell www.achilles.org th 2012 15 April – American Achilles Foundaon Dinner, at Harvard ‐ contact Tom Blodge [email protected] 16th April ‐ Oxford 7 Cambridge v Harvard & Yale – Harvard Saturday 27th April ‐ Achilles: Kinnaird/Sward Meeng – Kingston‐upon‐ Thames Sunday 28th April ‐ CUAC Sports ‐ Wilberforce Road 4‐6th May ‐ BUCS Outdoors ‐ Bedford Saturday 18th May ‐ Varsity Sports ‐ Wilberforce Road, Cambridge During the 1970’s and early 1980’s publicaon lapsed, and Achilles Dinner, at St Catharine’s. Chief Guest: Jon Ridgeon. Contact Tom Dowie when I revived it in 1986 it was in A4 format. Over the [email protected] years, as technology and my IT skills have improved I’ve Wednesday 29th May ‐ Achilles v Loughborough ‐ Loughborough sought to expand the content and refine its presentaon, Saturday 29 June ‐ Achilles, LICC Round One ‐ Allianz Park (formerly but always maintaining the style and identy of the Reports Copthall Stadium) of the Club’s first 50 years. -

2005 / 2006 the Racewalking Year in Review

2005 / 2006 THE RACEWALKING YEAR IN REVIEW COMPLETE VICTORIAN RESULTS MAJOR INTERNATIONAL RESULTS Tim Erickson 11 November 2006 1 2 Table of Contents AUSTRALIAN UNIVERSITY GAMES, QLD, 27-29 SEPTEMBER 2005......................................................................5 VICTORIAN SCHOOLS U17 – U20 TRACK AND FIELD CHAMPIONSHIPS, SAT 8 OCTOBER 2005...................6 VRWC RACES, ALBERT PARK, SUNDAY 23 OCTOBER 2005...................................................................................7 CHINESE NATIONAL GAMES, NANJING, 17-22 OCTOBER 2005 ..........................................................................10 VICTORIAN ALL SCHOOLS U12-U16 CHAMPIONSHIPS, OLYMPIC PARK, 29 OCTOBER 2005 .....................12 VRWC RACES, ALBERT PARK, SUNDAY 13 NOVEMBER 2005.............................................................................13 PACIFIC SCHOOLS GAMES, MELBOURNE, NOVEMBER 2005..............................................................................16 AUSTRALIAN ALL SCHOOLS CHAMPS, SYDNEY, 8-11 DECEMBER 2005..........................................................19 VRWC RACES, SUNDAY 11 DECEMBER 2005...........................................................................................................23 RON CLARKE CLASSIC MEET, GEELONG, 5000M WALK FOR ELITE MEN, SAT 17 DECEMBER 2005.........26 GRAHAM BRIGGS MEMORIAL TRACK CLASSIC, HOBART, FRI 6 JANUARY 2006..........................................28 NSW 5000M TRACK WALK CHAMPIONSHIPS, SYDNEY, SAT 7 JANUARY 2006...............................................29 -

Finland in the Olympic Games Medals Won in the Olympics

Finland in the Olympic Games Medals won in the Olympics Medals by winter sport Medals by summer sport Sport Gold Silver Bronz Total e Sport Gol Silv Bron Total Athletics 48 35 31 114 d er ze Wrestling 26 28 29 83 Cross-country skiing 20 24 32 76 Gymnastics 8 5 12 25 Ski jumping 10 8 4 22 Canoeing 5 2 3 10 Speed skating 7 8 9 24 Shooting 4 7 10 21 Nordic combined 4 8 2 14 Rowing 3 1 3 7 Freestyle skiing 1 2 1 4 Boxing 2 1 11 14 Figure skating 1 1 0 2 Sailing 2 2 7 11 Biathlon 0 5 2 7 Archery 1 1 2 4 Weightlifting 1 0 2 3 Ice hockey 0 2 6 8 Modern pentathlon 0 1 4 5 Snowboarding 0 2 1 3 Alpine skiing 0 1 0 1 Swimming 0 1 3 4 Curling 0 1 0 1 Total* 100 84 116 300 Total* 43 62 57 162 Paavo Nurmi • Paavo Johannes Nurmi born in 13th June 1897 • Was a Finnish middle-long-distance runner. • Nurmi set 22 official world records at distance between 1500 metres and 20 kilometres • He won a total of nine gold and three silver medals in his twelve events in the Olympic Games. • 1924 Olympics, Paris Lasse Virén • Lasse Arttu Virén was born in 22th July 1949. • He is a Finnish former long-distance runner • Winner of four gold medals at the 1972 and 1976 Summer Olympics. • München 10 000m Turin Olympics 2006 Ice Hockey • In the winter Olymipcs year 2006 in Turin, the Finnish ice hockey team won Russia 4-0 in the semifinal. -

Ultrarunning World Magazine Day! Great to Hear from Gary Dudney

ROAD, TRACK & TRAIL MULTIDAY & ULTRA DISTANCE NEWS // ISSUE 31 30 / 2021 | Ultrarunning World 1 2 Ultrarunning World | 30 / 2021 Editorial e are happy to welcome new members to the team with Sarah Thi helping on the editorial side. Dan Walker has sent Wus several articles and we are grateful for his interesting and helpful insights drawn from the depths of his ultrarunning experience. Gareth Chadwick has been working on material for our next publication which will be a Special Edition on the Dartmoor Discovery. We are grateful to Emily Adams who has been reviewing books for us. As the covid situation abates Emily is focussing more on her work as a physiotherapist and on her own running, she is leaving us with a review of Lowri Morgan’s latest book Beyond Limits. Another member of our correspondent team, Leila Majewska, (now Thompson) has set up Tough Trails with her husband Mike and we are very happy to support them and their vision to bring new and challenging events to the Peak District and beyond. Their first event will be the INFERNO – Edale’s Ring of Hell Ultra, Half Marathon & 10k We have also crossed paths with Blended Trails, a running community specialising in pop up trail routes in the countryside based in Medstead, Hampshire. Founded by Ollie Steele-Perkins in the Spring of 2020, the community is growing from strength to strength and will be holding Ultrarunning World their first event, the Hattingley Half on July 24th 2021 and later this year April 2021 they are planning on an ultra and we look forward to hearing about what goes down in Medstead. -

Vetrunner June 2008.Pub

VETRUNNER Email: [email protected] ISSN 1449-8006 Vol. 29 Issue 10 — June 2008 MAJURA — cool & crisp but a warm inner glow at the finish (Handicap report for 27th April 2008 by Geoff Barker) home in 19th position to claim the bronze medal. Emma found it rewarding to receive a medal especially after her Even though the balloons could not fly, the ACT Vets increased new handicap, and hopes it is an indication that (Masters?) flew around the Majura course like there was no her fitness level is improving each month. It was the most tomorrow. It was a cool, crisp morning with a bit of a chill challenging run Emma has attempted in her three months wind reminding us all that winter is here. Everyone also of running. She found the start the most difficult and warmed to see Marco Falzarano – albeit briefly do a bit of a thought the last bit before the turn ‘cruel’. However she jog/walk up the first 100 metres. And the absence of Alan enjoyed the end. She now feels competitive with Anthony, Duus, Jane Bell, Ros Pilkinton and John Littler has been Mike and Robyn and hopes it will not be too long before she noted! overtakes them all in the family medal tally. Daughter Mollie, who uses the childcare facilities, is not included. FRYLINK series Heather Koch, who was first over the line in April, First over the line was Carol Bennett, who became came home in 25th position. another of these women who simply ran off into the pale Tony Harrison, one of the most important people at blue cold day, and has not been seen since. -

NEWSLETTER Supplementingtrack & FIELD NEWS Twice Monthly

TRACKNEWSLETTER SupplementingTRACK & FIELD NEWS twice monthly. Vol. 10, No. 1 August 14, 1963 Page 1 Jordan Shuffles Team vs. Germany British See 16'10 1-4" by Pennel Hannover, Germany, July 31- ~Aug. 1- -Coach Payton Jordan London, August 3 & 5--John Pennel personally raised the shuffled his personnel around for the dual meet with West Germany, world pole vault record for the fifth time this season to 16'10¼" (he and came up with a team that carried the same two athletes that com has tied it once), as he and his U.S. teammates scored 120 points peted against the Russians in only six of the 21 events--high hurdles, to beat Great Britain by 29 points . The British athl_etes held the walk, high jump, broad jump, pole vault, and javelin throw. His U.S. Americans to 13 firsts and seven 1-2 sweeps. team proceeded to roll up 18 first places, nine 1-2 sweeps, and a The most significant U.S. defeat came in the 440 relay, as 141 to 82 triumph. the Jones boys and Peter Radford combined to run 40 . 0, which equal The closest inter-team race was in the steeplechase, where ed the world record for two turns. Again slowed by poor baton ex both Pat Traynor and Ludwig Mueller were docked in 8: 44. 4 changes, Bob Hayes gained up to five yards in the final leg but the although the U.S. athlete was given the victory. It was Traynor's U.S. still lost by a tenth. Although the American team had hoped second fastest time of the season, topped only by his mark against for a world record, the British victory was not totally unexpected. -

Success on the World Stage Athletics Australia Annual Report 2010–2011 Contents

Success on the World Stage Athletics Australia Annual Report Success on the World Stage Athletics Australia 2010–2011 2010–2011 Annual Report Contents From the President 4 From the Chief Executive Officers 6 From The Australian Sports Commission 8 High Performance 10 High Performance Pathways Program 14 Competitions 16 Marketing and Communications 18 Coach Development 22 Running Australia 26 Life Governors/Members and Merit Award Holders 27 Australian Honours List 35 Vale 36 Registration & Participation 38 Australian Records 40 Australian Medalists 41 Athletics ACT 44 Athletics New South Wales 46 Athletics Northern Territory 48 Queensland Athletics 50 Athletics South Australia 52 Athletics Tasmania 54 Athletics Victoria 56 Athletics Western Australia 58 Australian Olympic Committee 60 Australian Paralympic Committee 62 Financial Report 64 Chief Financial Officer’s Report 66 Directors’ Report 72 Auditors Independence Declaration 76 Income Statement 77 Statement of Comprehensive Income 78 Statement of Financial Position 79 Statement of Changes in Equity 80 Cash Flow Statement 81 Notes to the Financial Statements 82 Directors’ Declaration 103 Independent Audit Report 104 Trust Funds 107 Staff 108 Commissions and Committees 109 2 ATHLETICS AuSTRALIA ANNuAL Report 2010 –2011 | SuCCESS ON THE WORLD STAGE 3 From the President Chief Executive Dallas O’Brien now has his field in our region. The leadership and skillful feet well and truly beneath the desk and I management provided by Geoff and Yvonne congratulate him on his continued effort to along with the Oceania Council ensures a vast learn the many and numerous functions of his array of Athletics programs can be enjoyed by position with skill, patience and competence. -

2020 Yearbook

-2020- CONTENTS 03. 12. Chair’s Message 2021 Scholarship & Mentoring Program | Tier 2 & Tier 3 04. 13. 2020 Inductees Vale 06. 14. 2020 Legend of Australian Sport Sport Australia Hall of Fame Legends 08. 15. The Don Award 2020 Sport Australia Hall of Fame Members 10. 16. 2021 Scholarship & Mentoring Program | Tier 1 Partner & Sponsors 04. 06. 08. 10. Picture credits: ASBK, Delly Carr/Swimming Australia, European Judo Union, FIBA, Getty Images, Golf Australia, Jon Hewson, Jordan Riddle Photography, Rugby Australia, OIS, OWIA Hocking, Rowing Australia, Sean Harlen, Sean McParland, SportsPics CHAIR’S MESSAGE 2020 has been a year like no other. of Australian Sport. Again, we pivoted and The bushfires and COVID-19 have been major delivered a virtual event. disrupters and I’m proud of the way our team has been able to adapt to new and challenging Our Scholarship & Mentoring Program has working conditions. expanded from five to 32 Scholarships. Six Tier 1 recipients have been aligned with a Most impressive was their ability to transition Member as their Mentor and I recognise these our Induction and Awards Program to prime inspirational partnerships. Ten Tier 2 recipients time, free-to-air television. The 2020 SAHOF and 16 Tier 3 recipients make this program one Program aired nationally on 7mate reaching of the finest in the land. over 136,000 viewers. Although we could not celebrate in person, the Seven Network The Melbourne Cricket Club is to be assembled a treasure trove of Australian congratulated on the award-winning Australian sporting greatness. Sports Museum. Our new SAHOF exhibition is outstanding and I encourage all Members and There is no greater roll call of Australian sport Australian sports fans to make sure they visit stars than the Sport Australia Hall of Fame. -

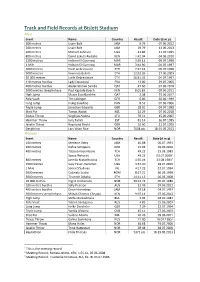

Track and Field Records at Bislett Stadium

Track and Field Records at Bislett Stadium Men Event Name Country Result Date (d.m.y) 100 metres Usain Bolt JAM 9.79 07.06.2012 200 metres Usain Bolt JAM 19.79 13.06.2013 400 metres Michael Johnson USA 43.86 21.07.1995 800 metres David Lekuta Rudisha KEN 1:42.04 04.06.2010 1500 metres Hicham El Guerrouj MAR 3:29.12 09.07.1998 1 Mile Hicham El Guerrouj MAR 3:44.90 04.07.1997 3000 metres Haile Gebrselassie ETH 7:27.42 09.07.1998 5000 metres Kenenisa Bekele ETH 12:52.26 27.06.2003 10 000 metres Haile Gebreslassie ETH 26:31.32 04.07.1997 110 metres hurdles Ladji Doucouré FRA 13.00 29.07.2005 400 metres hurdles Abderrahman Samba QAT 47.60 07.06.2018 3000 metres steeplechase Paul Kipsiele Koech KEN 8:01.83 09.06.2011 High Jump Mutaz Essa Barshim QAT 2.38 15.06.2017 Pole Vault Tim Lobinger GER 6.00 30.06.1999 Long Jump Irving Saladino PAN 8.53 02.06.2006 Triple Jump Jonathan Edwards GBR 18.01 09.07.1998 Shot Put Tomas Walsh NZL 22.29 07.06.2018 Discus Throw Virgilijus Alekna LTU 70.51 15.06.2007 Hammer Throw Jurij Tamm EST 81.14 16.07.1985 Javelin Throw Raymond Hecht GER 92.60 21.07.1995 Decathlon Lars Vikan Rise NOR 7608 pts 18-19.05.2013 Women Event Name Country Result Date (d.m.y) 100 metres Merlene Ottey JAM 10.88 06.07.1991 200 metres Dafne Schippers NED 21.93 09.06.2016 400 metres Tatjana Kocembova TCH 49.23 23.08.1983 Sanya Richards USA 49.23 03.07.20091 800 metres Jarmila Kratochvilova TCH 1:55.04 23.08.19832 1500 metres Suzy Favor-Hamilton USA 3:57.40 28.07.2000 1 Mile Sonia O'Sullivan IRL 4:17.25 22.07.1994 3000 metres Gabriela Szabo -

Athletics SA 2021 State Track and Field Championships

Athletics SA 2021 State Track and Field Championships Final Timetable - as at 25/2/2021 Friday - 26th February Day Time Event Age Group Round Long Jump Triple Jump High Jump Pole Vault Shot Put Discus Javelin Hammer Fri 6.30 PM 3000 metres Walk Under 14 Men & Women FINAL 6.30 PM U17/18/20 Women Fri 3000 metres Walk Under 15 Men & Women FINAL Fri 3000 metres Walk Under 16 Men & Women FINAL Fri 5000 metres Walk Under 17 Men & Women FINAL 6.35 PM U17/18/20 Women Fri 5000 metres Walk Under 18 Men & Women FINAL Fri 5000 metres Walk Under 20 Women FINAL Fri 5000 metres Walk Under Open Women FINAL Fri 5000 metres Walk Under 20 Men FINAL Fri 5000 metres Walk Under Open Men FINAL Fri 5000 metres Walk Over 35 & Over 50 Men & FINAL 6.40 PM Women U14/15/16 Men Fri 6.45 PM 6.45 PM U15/16/U20 Women Fri 6.50 PM 6.50 PM Fri 6.55 PM 6.55 PM Fri 7.00 PM 200 metres Hurdles Under 15 Women FINAL 7.00 PM Fri 200 metres Hurdles Under 16 Women FINAL Fri 7.05 PM 200 metres Hurdles Under 15 Men FINAL 7.05 PM Fri 200 metres Hurdles Under 16 Men FINAL Fri 7.10 PM 200 metres Hurdles Over 35 & Over 50 Men & FINAL 7.10 PM Women Fri 7.15 PM 7.15 PM O35/O50 Women Fri 7.20 PM 400 metres Hurdles Open Men FINAL 7.20 PM Fri 400 metres Hurdles Under 20 Men FINAL 7.25 PM Fri 7:30 PM 400 metres Hurdles Under 17 Men FINAL 7.30 PM Fri 400 metres Hurdles Under 18 Men FINAL Fri 7.35 PM 7.35 PM Open Women Fri 7:40 PM 400 metres Hurdles Under 17 Women FINAL 7.40 PM Seated Fri 400 metres Hurdles Under 18 Women FINAL 7.45 PM U17/18/20 Men U17/18/20 Men Fri 7.50 PM 800 metres Open Men -

Payton Jordan.Pdf

p.1 STANFORD UNIVERSITY PROJECT: Bob Murphy Interviews INTERVIEWEE: Payton Jordan Robert W. Murphy, Jr.: [0:00] Hello again everybody, Bob Murphy here and a very special chapter in Stanford sports today because one of the dearest friend I've ever had in my life and one of my great pals, Payton Jordan, is with us. Payton, this was scheduled long before you hit your little speed bump a week or so ago. So we'll tell the folks about that, but as we start doing this, I think of you and I sharing the better part of the last 50 years telling stories to one another. Laughing with one another. Laughing at one another. [laughter] Murphy: [0:38] But here we are to recap this. Tell the folks about your little speed bump, you're doing fine, you look great, things are gonna be fine. Payton Jordan: [0:46] I'm sure everything will be fine, I had a slight bump in road, had a little lump on my neck. And they found out it was a very rare cancer and we had to do a little cutting and we'll be doing some radiation and in no time at all, I'll be back up and at them. Murphy: [1:00] They didn't give you a face lift, too, because you're looking so pretty here. [both laugh] Jordan: [1:05] They kind of knit my nerves on one side a little bit, but I'm going to be OK. Murphy: [1:09] We're going to have fun talking about this, we're in no hurry, we're just gonna kind of ramble on. -

Amateurism and Coaching Traditions in Twentieth Century British Sport

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by E-space: Manchester Metropolitan University's Research Repository Uneasy Bedfellows: Amateurism and Coaching Traditions in Twentieth Century British Sport Tegan Laura Carpenter A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements of the Manchester Metropolitan University for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy July 2012 Tegan Carpenter July 2012 If you do well in sport and you train, ‘good show’, but if you do well in sport and you don’t train, ‘bloody good show’. Geoffrey Dyson, 1970 Tegan Carpenter July 2012 Dedication This thesis is proudly dedicated to my parents, Lynne and John, my two brothers, Dan and Will and my best friend, Steve - Thank you for always believing in me. Tegan Carpenter July 2012 Acknowledgments This thesis would not have been possible without the continued support of family, friends and colleagues. While I am unable to acknowledge you all individually - I will be forever indebted to you. To my supervisor, Dr Dave Day - I consider myself incredibly lucky to have had such an attentive and committed mentor. Someone who transformed the trudge of a PhD into an enjoyable journey, and because of this, I would not hesitate accepting the opportunity again (even after knowing the level of commitment required!). Thank you for never losing faith in me and for your constant support and patience along the way. I would also like to thank Dr Neil Carter and Professor Martin Hewitt for their comments and advice. Special thanks to Sam for being the best office buddy and allowing me to vent whenever necessary! To Margaret and the interviewees of this study – thank you for your input and donating your time.