Urban Reconstruction, Development and Planning in the New South Africa

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

South Africa: Economic Progress and Failures Since 1994

Università degli Studi di Padova Dipartimento di Studi Linguistici e Letterari Corso di Laurea Magistrale in Lingue Moderne per la Comunicazione e la Cooperazione Internazionale Classe LM-38 Tesi di Laurea South Africa: economic progress and failures since 1994 Laureando Relatore Monica Capuzzo Prof. Antonio Covi n° matr.1061228 / LMLCC Anno Accademico 2014 / 2015 South Africa: economic progress and failures since 1994 1 INTRODUCTION….…………………………………………………….. p. 1 2 SOUTH AFRICA: A GENERAL OVERVIEW..………………………... p. 3 2.1 A brief geographical description ………………………………………… p. 3 2.2 Historical background……………………………………………………. p. 5 2.2.1 The colonial age………………………………………………….. p. 6 2.2.2 The rise of Apartheid…………………………………………….. p. 7 2.2.3 The end of Apartheid and the birth of democracy……………….. p. 8 2.3 Political institutions and their historical development…………………... p. 9 2.3.1 Government structure during Apartheid…………………………. p. 9 2.3.2 South Africa’s Constitution………………………………………. p. 10 2.3.3 Institutions supporting democracy………………………………… p. 13 2.4 Social and economic consequences of Apartheid………………………… p. 15 2.4.1 Demography and racial discrimination……………………………. p. 16 2.4.2 GDP per capita and poverty rate…………………………………... p. 22 2.4.3 Income inequality and the gap between the rich and the poor…….. p. 28 2.4.4 Life expectancy and health care…………………………………… p. 30 2.4.5 Primary education…………………………………………………. p. 37 2.4.6 Employment……………………………………………………….. p. 40 2.4.7 The Human Development Index (HDI)…………………………… p. 44 3 SOUTH AFRICAN ECONOMY SINCE THE END OF APARTHEID… p. 51 3.1 Economic structure today………………………………………………… p. 51 3.2 Economic reforms………………………………………………………… p. 60 3.2.1 Land and agrarian reform…………………………………………. -

The Church As a Peace Broker: the Case of the Natal Church Leaders' Group and Political Violence in Kwazulu-Natal (1990-1994)1

The Church as a peace broker: the case of the Natal Church Leaders’ Group and political violence in KwaZulu-Natal (1990-1994)1 Michael Mbona 2 School of Religion and Theology, University of KwaZulu-Natal, Pietermaritzburg, South Africa Abstract Moves by the state to reform the political landscape in South Africa at the beginning of 1990 led to increased tension between the Inkatha Freedom Party and the African National Congress in the province of Natal and the KwaZulu homeland. Earlier efforts by the Natal Church Leaders’ Group to end hostilities through mediation had yielded minimal results. Hopes of holding the first general democratic election in April 1994 were almost dashed due to Inkatha’s standoff position until the eleventh hour. This article traces the role played by church leaders in seeking to end the bloody clashes taking place at that time by engaging with the state and the rival political parties between 1990 and 1994. Despite the adoption of new strategies, challenges such as internal divisions, blunders at mediation, and the fact that the church leaders were also “political sympathisers”, hampered progress in achieving peace. While paying tribute to the contribution of other team players, this article argues that an ecumenical initiative was responsible for ending the politically motivated brutal killings in KwaZulu-Natal in the early years of 1990. Introduction The announcement in 1990 by State President FW de Klerk about the release of political prisoners, including Nelson Mandela, and the unbanning of all political parties was a crucial milestone on the journey towards reforming the South African political landscape.3 While these reforms were acclaimed by progressive thinkers within and outside South Africa, tension between 1 This article follows on, as part two, from a previous article by the same author. -

From Apartheid to Neoliberalism

From Apartheid to Neoliberalism - A study of the Economic Development in Post-Apartheid South Africa By Thomas Bakken Abstract This thesis describes the social and economic development in Post-Apartheid South Africa and the role of neoliberal advocates in the shaping of the country‘s broader developmental path after 1994. South Africa‘s ruling party, the African National Congress (ANC), inherited a two folded legacy. On the one hand it took over the most developed economy on the African continent. On the other, a legacy of massive inequality and racial segregation. This thesis describes why a neoliberal trajectory was triumphant in the crossroad where the ANC had the choice between following a progressive developmental path or a neoliberal one, and its impact on South Africa‘s social and economic system. i ii Acknowledgements - I thank Professor Moses for his patience, comments and insights in helping this thesis to completion. - I also thank my one and only: Nina iii iv Content 1.1 - Background and motivation ........................................................................................... 1 1.2 - My argument .................................................................................................................. 3 1.3 - Problem statement ......................................................................................................... 3 1.4 - Research aims ................................................................................................................. 4 1.5 - Research design and methodology -

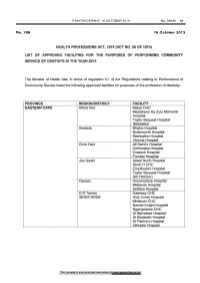

Health Professions Act: List of Approved Facilities for the Purposes of Performing Community Service by Dentists in the Year

STAATSKOERANT, 16 OKTOBER 2013 No. 36936 13 No. 788 16 October 2013 HEALTH PROFESSIONS ACT, 1974 (ACT NO. 56 OF 1974) LIST OF APPROVED FACILITIES FOR THE PURPOSES OF PERFORMING COMMUNITY SERVICE BY DENTISTS IN THE YEAR 2014 The Minister of Health has, in terms of regulation 5.1 of the Regulations relating to Performance of Community Service listed the following approved facilities for purposes of the profession of dentistry. PROVINCE REGION/DISTRICT FACILITY EASTERN CAPE Alfred Nzo Maluti CHC Madzikane Ka Zulu Memorial Hospital Taylor Bequest Hospital (Matatiele) Amato le Bhisho Hospital Butterworth Hospital Madwaleni Hospital Victoria Hospital Chris Hani All Saint's Hospital Cofimvaba Hospital Cradock Hospital Frontier Hospital Joe Gqabi Aliwal North Hospital Block H CHC Empilisweni Hospital Taylor Bequest Hospital (Mt Fletcher) Cacadu Humansdorp Hospital Midlands Hospital Settlers Hospital O.R Tambo Gateway CHC ISRDS NODE Holy Cross Hospital Mhlakulo CHC Nessie Knight Hospital Ngangelizwe CHC St Barnabas Hospital St Elizabeth Hospital St Patrick's Hospital Zithulele Hospital This gazette is also available free online at www.gpwonline.co.za 14 No. 36936 GOVERNMENT GAZETTE, 16 OCTOBER 2013 FREE STATE Motheo District(DC17) National Dental Clinic Botshabelo District Hospital Fezile Dabi District(DC20) Kroonstad Dental Clinic MafubefTokollo Hospital Complex Metsimaholo/Parys Hospital Complex Lejweleputswa DistrictWelkom Clinic Area(DC18) Thabo Mofutsanyana District Elizabeth Ross District Hospital* (DC19) Itemoheng Hospital* ISRDS NODE Mantsopa -

The Constitution of South Africa of 1996 (Bill of Rights /Chapter Two)

University of Oran 2 Faculty of Foreign Languages THESIS In Candidacy for the Degree of Doctorate in Science, English Language. THE AFRICAN NATIONAL CONGRESS IN TRANSITION: FROM A RESISTANCE MOVEMENT TO A GOVERNING PARTY (1961-1999) Publicly Presented by: Mrs DEHMOUNE AMEL Before a Jury Composed of: Benhattab Abdelkader Professor University of Oran 2 President Moulfi Leila Professor University of Oran 2 Supervisor Meberbeche Faiza Professor University of Tlemcen Examiner Dani Fatiha MCA University of Oran 1 Examiner Academic Year 2018/2019 University of Oran 2 Faculty of Foreign Languages THESIS In Candidacy for the Degree of Doctorate in Science, English Language. THE AFRICAN NATIONAL CONGRESS IN TRANSITION: FROM A RESISTANCE MOVEMENT TO A GOVERNING PARTY (1961-1999) Publicly Presented by: Mrs DEHMOUNE AMEL Before a Jury Composed of: Benhattab Abdelkader Professor University of Oran 2 President Moulfi Leila Professor University of Oran 2 Supervisor Meberbeche Faiza Professor University of Tlemcen Examiner Dani Fatiha MCA University of Oran 1 Examiner Academic Year 2018/2019 I DECLARATION I hereby declare that this dissertation is the result of my original research. References to other people’s research have been duty cited and acknowledged in this research work accordingly. Amel DEHMOUNE II Dedication “No one in this world can love a girl more than her father “ Michael Ratnadeepak To my everlasting love, my beloved father, Mr. DEHMOUNE Mohammed III ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS First of all, I shall thank Almighty Allah for all His blessings. I would like to express my deepest gratefulness to my supervisor Prof. Leila Moulfi for the continuous support, patience and motivation throughout the writing of this thesis. -

Community Struggle from Kennedy Road Jacob Bryant SIT Study Abroad

SIT Graduate Institute/SIT Study Abroad SIT Digital Collections Independent Study Project (ISP) Collection SIT Study Abroad Fall 2005 Towards Delivery and Dignity: Community Struggle From Kennedy Road Jacob Bryant SIT Study Abroad Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcollections.sit.edu/isp_collection Part of the Politics and Social Change Commons, and the Race and Ethnicity Commons Recommended Citation Bryant, Jacob, "Towards Delivery and Dignity: Community Struggle From Kennedy Road" (2005). Independent Study Project (ISP) Collection. 404. https://digitalcollections.sit.edu/isp_collection/404 This Unpublished Paper is brought to you for free and open access by the SIT Study Abroad at SIT Digital Collections. It has been accepted for inclusion in Independent Study Project (ISP) Collection by an authorized administrator of SIT Digital Collections. For more information, please contact [email protected]. TOWARDS DELIVERY AND DIGNITY: COMMUNITY STRUGGLE FROM KENNEDY ROAD Jacob Bryant Richard Pithouse, Center for Civil Society School for International Training South Africa: Reconciliation and Development Fall 2005 “The struggle versus apartheid has been a little bit achieved, though not yet, not in the right way. That’s why we’re still in the struggle, to make sure things are done right. We’re still on the road, we’re still grieving for something to be achieved, we’re still struggling for more.” -- Sbusiso Vincent Mzimela “The ANC said ‘a better life for all,’ but I don’t know, it’s not a better life for all, especially if you live in the shacks. We waited for the promises from 1994, up to 2004, that’s 10 years of waiting for the promises from the government. -

History Workshop

UNIVERSITY OF THE WITWATERSRAND, JOHANNESBURG HISTORY WORKSHOP STRUCTURE AND EXPERIENCE IN THE MAKING OFAPARTHEID 6-10 February 1990 AUTHOR: Iain Edwards and Tim Nuttall TITLE: Seizing the moment : the January 1949 riots, proletarian populism and the structures of African urban life in Durban during the late 1940's 1 INTRODUCTION In January 1949 Durban experienced a weekend of public violence in which 142 people died and at least 1 087 were injured. Mobs of Africans rampaged through areas within the city attacking Indians and looting and destroying Indian-owned property. During the conflict 87 Africans, SO Indians, one white and four 'unidentified' people died. One factory, 58 stores and 247 dwellings were destroyed; two factories, 652 stores and 1 285 dwellings were damaged.1 What caused the violence? Why did it take an apparently racial form? What was the role of the state? There were those who made political mileage from the riots. Others grappled with the tragedy. The government commission of enquiry appointed to examine the causes of the violence concluded that there had been 'race riots'. A contradictory argument was made. The riots arose from primordial antagonism between Africans and Indians. Yet the state could not bear responsibility as the outbreak of the riots was 'unforeseen.' It was believed that a neutral state had intervened to restore control and keep the combatants apart.2 The apartheid state drew ideological ammunition from the riots. The 1950 Group Areas Act, in particular, was justified as necessary to prevent future endemic conflict between 'races'. For municipal officials the riots justified the future destruction of African shantytowns and the rezoning of Indian residential and trading property for use by whites. -

National Water

STAATSKOERANT, 7 DESEMBER 2018 No. 42092 69 DEPARTMENT OF WATER AND SANITATION NO. 1366 07 DECEMBER 2018 1366 National Water Act, 1998: Mzimvubu-Tsitsikamma Water Management Area (WMA7) in the Eastern Cape Province: Amending and Limiting the use of Water in terms of Item 6 of Schedule 3 of the Act, for Urban, Agricultural and Industrial (including Mining) purposes 42092 MZIMVUSU- TSIT$IKAMMA WATER MANAGEMENT AREA (WMA 7)IN THE EASTERN CAPE PROVINCE: AMENDING AND LIMITING THE USE OF WATER IN TERMSOF ITEM 6 OF SCHEDULE 3 OF THE NATIONAL WATER ACT OF 1998;FOR URBAN, AGRICULTURAL AND INDUSTRIAL (INCLUDING MINING) PURPOSES The Minister of Water and Sanitation has, in terms of item 6(1) of Schedule 3of the National Water Act of 1998 (Act 36 of 1998) (The Act), empowered to limit theuse of water in the area concerned if the Minister, on reasonable grounds, believes that a watershortage exists within the area concerned. This power has been delegated to me in terms of Section63 (1) (b) of the Act. Therefore,I,Deborah Mochotlhi, in my capacity as the Acting Director -Generalof the Department of Water and Sanitation hereby under delegated authority, interms of item 6 (1) of Schedule 3 read with section 72(1) of the Act, publish a notice in the gazetteto amend and limit the taking and storing of water in terms of section 21(a) and 21(b) byall users in the geographical areas listed and described below, as follows: 1. The Algoa Water Supply System (WSS) and associated primary catchments: Decrease the curtailment from 30% to 25% on all taking of waterfrom surface or groundwater resources for domestic and industrial water use from the Algoa WSS and the relevant parts of the catchments within which the Algoa WSSoccurs. -

Nkandlagate: Only Partial Evidence of Urban African Inequality Ruvimbo Moyo

Nkandlagate: Only Partial Evidence of Urban African Inequality Ruvimbo Moyo 160 Moyo Downloaded from http://www.mitpressjournals.org/doi/pdf/10.1162/thld_a_00065 by guest on 26 September 2021 Nkandlagate: Only Partial nce of Evide Were we really shocked by the R246 million (US$24 million) upgrade to South African Pres- ident Jacob Zuma's Nkandla residence? It was not a new concept. It was not a new architec- African ture. In the “Secure in Comfort” Report by the Public Protector of the Republic of South Afri- Urban ca, Thuli Madonsela investigated the impropri- ety in the implementation of security measures on President Zuma’s private home. 1 Madonse- la found ethical violations on the president’s part with respect to the project: his fam- quality ily benefited from the visitor center, cattle Ine kraal, chicken run, amphitheatre and swim- ming pool among others, built in the name of security. The president also violated the Ex- ecutive Ethics Code after failing to contain the cost when the media first reported the 2 1 then R65 million project in 2009. So-called Madonsela, T N. 2014. Secure In Com- “Nkandlagate” did not move from the Afri- fort: A Report of The Public Protector. can political norm that says loud and clear: Investigation Report 25 of 2013/14, Pub- lic Protector South Africa. 2 Rossouw, M. 2009. "Zuma's R65m Nkandla splurge." Mail & Guardian. December 04. Accessed 12 29, 2014. http://mg.co.za/article/2009-12- 04-zumas-r65m-nkandla-splurge. Moyo 161 Downloaded from http://www.mitpressjournals.org/doi/pdf/10.1162/thld_a_00065 by guest on 26 September 2021 Opulence is an acceptable perk for our leaders, a craving, an urge, a right. -

Location in Africa the Durban Metropolitan Area

i Location in Africa The Durban Metropolitan area Mayor’s message Durban Tourism am delighted to welcome you to Durban, a vibrant city where the Tel: +27 31 322 4164 • Fax: +27 31 304 6196 blend of local cultures – African, Asian and European – is reected in Email: [email protected] www.durbanexperience.co.za I a montage of architectural styles, and a melting pot of traditions and colourful cuisine. Durban is conveniently situated and highly accessible Compiled on behalf of Durban Tourism by: to the world. Artworks Communications, Durban. Durban and South Africa are fast on their way to becoming leading Photography: John Ivins, Anton Kieck, Peter Bendheim, Roy Reed, global destinations in competition with the older, more established markets. Durban is a lifestyle Samora Chapman, Chris Chapman, Strategic Projects Unit, Phezulu Safari Park. destination that meets the requirements of modern consumers, be they international or local tourists, business travellers, conference attendees or holidaymakers. Durban is not only famous for its great While considerable effort has been made to ensure that the information in this weather and warm beaches, it is also a destination of choice for outdoor and adventure lovers, eco- publication was correct at the time of going to print, Durban Tourism will not accept any liability arising from the reliance by any person on the information tourists, nature lovers, and people who want a glimpse into the unique cultural mix of the city. contained herein. You are advised to verify all information with the service I welcome you and hope that you will have a wonderful stay in our city. -

Introduction

1 introduction Before Dudley: Oppression, Racism, and the Roots of Resistance Much has been written about the fight against apartheid in South Africa, and now, with a continuing flow of publications on the Truth and Recon- ciliation Commission hearings, we are presented with a unique expanse of stories from the ground. Richard Dudley is one of the fighters. He is an urban educator and political activist who combined foundational ideological poli- tics with great caring, communication, and even compromise as a teacher and nominal principal at Livingstone High School, a highly rated public secondary school that was created for coloured students in 1926. In addition to teaching, Dudley worked endlessly, through various political organiza- tions, against apartheid oppression and for a democratic South Africa. Rich- ard Dudley’s life offers us multiple lenses for understanding apartheid South Africa. Dudley is truly a public intellectual, and that in itself is an important story. He is also totally and thoughtfully entwined with the life of Livingstone—first as a student, then as a teacher/principal, and presently as an elder. Finally, Richard Dudley has given his life to teaching and politics and affected and influenced thousands of people who continue to work for democracy in South Africa and abroad. Dudley’s life is totally entwined with education and politics, Livingstone High School, Cape Town, and democracy in South Africa. Dudley’s biogra- phy gives us the chance to explore the connection of education and politics in Cape Town as he and his comrades challenged first oppression and then apartheid. Dudley was born in 1924 and his story takes us through the many twentieth-century changes in South African oppression and resistance. -

DURBAN NORTH 957 Hillcrest Kwadabeka Earlsfield Kenville ^ 921 Everton S!Cteelcastle !C PINETOWN Kwadabeka S Kwadabeka B Riverhorse a !

!C !C^ !.ñ!C !C $ ^!C ^ ^ !C !C !C!C !C !C !C ^ ^ !C !C ^ !C !C !C !C !C ^ !C ñ !C !C !C !C !C ^ !C !C ^ !C !C $ !C ^ !C !C !C !C !C !C ^ !C ^ ñ !C !C !C !C !C !C !C !C !C !C !C !C !. !C ^ ñ ^ !C !C !C !C !C !C $ !C !C ^ !C ^ !C !C !C ñ !C !C !C ^ !C !.ñ ñ!C !C !C !C ^ !C ^ !C ^ !C ^ !C !C !C !C !C !C !C !C ^ ñ !C !C !C !C !C !C ^ ñ !C !C ñ !C !C !C !C !C !C !C !C !C !C !C !C ñ !C !C ^ ^ !C !C !. !C !C ñ ^ !C ^ !C ñ!C !C ^ ^ !C !C $ ^!C $ ^ !C !C !C !C !C !C !C !C !C !C !. !C !C !C ñ!.^ $ !C !C !C ^ !C !C !C !C $ !C ^ !C !C $ !C !C ñ $ !. !C !C !C !C !C !C !. ^ ñ!C ^ ^ !C $!. ^ !C !C !C !C !C !C !C !C !C !C !C !C !C !. !C !C !C !C !C ^ !C !. !C !C ñ!C !C !C !C ^ ñ !C !C ñ !C !C !. ^ !C !C !C !C !C !C !C ^ !C ñ ^ $ ^ !C ñ !C !C !. ñ ^ !C !. !C !C ^ ñ !. ^ ñ!C !C $^ ^ ^ !C ^ ñ ^ !C ^ !C !C !C !C !C !C ^ !C !C !C !C !C !C !C !C !. !C ^ !C $ !C !. ñ !C !C ^ !C ñ!. ^ !C !C !C !C !C !C !C !C $!C !. !C ^ !. !. !C !C !. ^ !C !C !C ^ ^ !C !C ñ !C !.