MUSICKING at HOME on the WOOD THAT SINGS: CONTEMPORARY MARIMBA PERFORMANCE PRACTICES in ZIMBABWE by WONDER MAGURAUSHE Submitted

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

9-28-13 Vs Bellarmine.Indd

LIMESTONE COLLEGE FIELD HOCKEY Bellarmine University (1-4) vs. No. 6 Limestone College (6-2) September 28, 2013 • Timken Field • 1 p.m. About The Match-Up 22013013 LLimestoneimestone FFieldield HHockeyockey GGameame DDayay PProgramrogram No. 6 Limestone (6-2) takes on Bellarmine (1-4) in the second game of a ((6-2)6-2) three-game homestand at Timken Field. DDateate OOpponentpponent TTime/Resultime/Result Scouting No. 6 Limestone College Saints (6-2) Sept. 5 at Newberry W, 7-1 In Recent Action Sept. 8 No. 6 Indiana (Pa.) W, 3-2 In their second straight week of being nationally ranked, the Saints showed Sept. 13 at Mercyhurst L, 3-1 they clearly intend to stay there with a convincing 5-2 victory over a solid Linden- wood program. Sept. 14 ^vs. No. 9 East Stroudsburg W, 2-1 They wasted no time as Rachel Goromonzi, one of the leading scorers in the Sept. 21 at Dowling W, 4-1 country, showed in the fi rst minute of play why she is ranked so highly. She raced Sept. 22 at Mercy W, 3-1 down fi eld just 43 seconds in and delivered a shot from the left side to the right Sept. 23 at Adelphi L, 1-0 corner of the cage for goal number eight on the season. Sept. 27 Lindenwood W, 6-2 It wouldn’t take long for her to collect number nine as she replicated the same Sept. 28 Bellarmine 1 p.m. play just 17 seconds later, this time connecting from the left side for a 2-0 lead at Oct. -

A Look at the Influence of Celebrity Endorsement on Customer Purchase Intentions: the Case Study of Fast Foods Outlet Companies in Harare, Zimbabwe

Vol. 11(15), pp. 347-356, 14 August, 2017 DOI: 10.5897/AJBM2017.8357 Article Number: 1F480E865441 ISSN 1993-8233 African Journal of Business Management Copyright © 2017 Author(s) retain the copyright of this article http://www.academicjournals.org/AJBM Full Length Research Paper Midas touch or time bomb? A look at the influence of celebrity endorsement on customer purchase intentions: The case study of fast foods outlet companies in Harare, Zimbabwe Jacob Shenje Business Research Consultancy (B.R.C) Pvt Ltd, 5 Rutledge Street, Milton Park Harare, Zimbabwe. Received 14 June, 2017; Accepted 6 July, 2017 Fast foods companies in Zimbabwe have been outcompeting and outclassing each other in using celebrity endorsers for their marketing communications. The study aimed to investigate the impact of celebrity endorsement on consumer purchase intentions. The study’s literature review was based on a copious of celebrity endorsement empirical and theoretical literature. The literature review also acted as bedrock for the research methodology which was later adopted. In order to achieve the research objectives, the study was largely quantitative where survey questionnaires were distributed to customers and these questionnaires were useful in the aggregation of the results. The findings were entered into SPSS software package version 22. The result shows that celebrity endorsement variables showed a positive and significant statistical relationship with consumer buying intentions. The study recommends for fast foods companies to gauge the capacity of celebrities to project multi-attributes which would be consistent and of interest to the consumer’s requirements. There is also the need to strengthen certain aspects of celebrity consumer relationship as way of understanding the implications for product endorsement in the fast foods industry. -

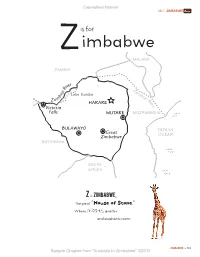

Z Is for Zimbabwe – Sample Chapter from Book

Copyrighted Material MEET ZIMBABWE! is for Zimbabwe MALAWI Z ZAMBIA a m b e z i r R ive i v R Z e i a r z m e Lake Kariba b b ez m i Za Ri NAMIBIA HARARE ve Victoria r Falls MUTARE MOZAMBIQUE BULAWAYO Great INDIAN Zimbabwe OCEAN BOTSWANA SOUTH AFRICA Z is Zimbabwe, the great “House of Stone,” Where zebras, giraffes and elephants roam. ZIMBABWE 311 Sample Chapter from "Australia to Zimbabwe" ©2015 Copyrighted Material MEET ZIMBABWE! Here you can hear the mbira’s soft sounds [em-BEER-rah] Calling the ancestors Mbira out of the ground. (Thumb Piano) Here Victoria Falls Victoria Falls from the river Zambezi, [zam-BEE-zee] “Mosi oa Tunya” And across the plateau, the weather is easy. Here men find great sculptures hidden in stones, Stone Sculpture Near fields where tobacco and cotton are grown. But their food is from corn Cotton served with sauce (just like pasta) – For breakfast there’s bota, for dinner there’s sadza. Once a colony British called Southern Rhodesia, Sadza This nation was founded on historic amnesia Bota 312 ZIMBABWE Sample Chapter from "Australia to Zimbabwe" ©2015 Copyrighted Material MEET ZIMBABWE! Brits believed civilization arrived with the whites, Who soon took the best land and had all the rights. Cecil Rhodes Rhodesia’s Founder They couldn’t believe Great Zimbabwe had been Great Zimbabwe Constructed by locals – by those with black skin. This fortress in ruins from medieval times Bird Sculpture from Had been city and home Great Zimbabwe to a culture refined. White settlers built cities Great Zimbabwe and farms in this place, And blacks became second class due to their race. -

THE GATE Go Through His Gates, Giving Thanks; Walk Through His Courts, Giving Praise

THE GATE Go through His gates, giving thanks; walk through His courts, giving praise. Offer Him your gratitude and praise His holy name. Psalm 100:4 Inside this issue: 2019, Issue 2 April 2019 CONGRATULATIONS From the Headmas- 2 ter‟s Desk Academic Colours Cross-country and 3 Athletics Colours Career Fair 2019 Cyclone Idai 4 - 5 Inter-house Athletics 6 - 7 Donata Breaks Record 8 Netball Tour 9 Eisteddfod Results 10 Eisteddfod in Photos 11 Sports Results 12 EVENTS OF NOTE Rugby Festival: 29 April - 4 May Hockey Festival: 2 –4 Mays Cambridge May/June exams begin: 2 May School opening Day :7 May Career Fair :20 June We would like to congratulate Hannah for winning two honours in the African Contemporary Solo and Musical Theatre categories of the 2019 Eisteddfod Concert. EISTEDDFOD CONCERT HONOURS AWARDS Soloists: Hannah Goto Musical Theatre: Vimbisodzashe Maanda and Hannah Goto Ensembles: Ethnic Ensemble Accompanied Remember your Creator in the days of your youth , Ecclesiastes 12:1 Page 2 Equipping students to reach their full potential 2019, Issue 2 FROM THE HEADMASTER’S DESK As we have come to the end of a very long but successful We bid farewell to Mr Tinashe Jera, we are appreciative first term, we would like to thank God for seeing us his brief service at Gateway High in the Music depart- through, it has been indeed a hectic and challenging term. ment. His passion and enthusiasm for music saw a num- ber of our students achieve honours in the recent Ei- Congratulations to all students and teachers for the con- steddfod concert under his mentorship. -

An Investigation Into the Effectiveness Of

An investigation into the effectiveness of corporate sustainability programmes and initiatives in the agricultural sector: The case of British American Tobacco Zimbabwe by Stanley Nyanyirai Thesis presented in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Philosophy in Sustainable Development Planning & Management in the Faculty of Economic and Management Sciences at Stellenbosch University Supervisor: Professor Alan Brent March 2013 Stellenbosch University http://scholar.sun.ac.za Declaration by the Student By submitting this work electronically or physically, I hereby do declare that the totality of the work herein is my own, being original, and I am the sole researcher (except to the extent indicated). In consultation with BAT Zimbabwe the reproduction and publication in electronic, physical and any other form by the University of Stellenbosch will not infringe any third party rights. I have not previously, in its entirety or in part, submitted this work for obtaining any other academic or professional qualification elsewhere. Copyright(c) 2013 Stellenbosch University All rights reserved - 1 - Stellenbosch University http://scholar.sun.ac.za Abstract In recent years, a great deal of attention has been paid towards the notion of corporate sustainability, which has variously been defined as meaning the incorporation of social, environmental, economic, and cultural concerns into corporate strategy and bottom line. The preliminary investigation suggests that Multi-National Corporations (MNCs) are mainly worried about securing permission for commencing operations and not about the wellbeing of locals and their livelihoods. Further to this, one of the main reasons why efforts aimed at improving sustainability are not yielding significant and lasting results, is that solution seekers in business, science, government and the research community are still operating in the same old paradigm of using basically the same tools and adopting the same world view that threaten sustainability in the first. -

Human Rights for Musicians Freemuse

HUMAN RIGHTS FOR MUSICIANS FREEMUSE – The World Forum on Music and Censorship Freemuse is an international organisation advocating freedom of expression for musicians and composers worldwide. OUR MAIN OBJECTIVES ARE TO: • Document violations • Inform media and the public • Describe the mechanisms of censorship • Support censored musicians and composers • Develop a global support network FREEMUSE Freemuse Tel: +45 33 32 10 27 Nytorv 17, 3rd floor Fax: +45 33 32 10 45 DK-1450 Copenhagen K Denmark [email protected] www.freemuse.org HUMAN RIGHTS FOR MUSICIANS HUMAN RIGHTS FOR MUSICIANS Ten Years with Freemuse Human Rights for Musicians: Ten Years with Freemuse Edited by Krister Malm ISBN 978-87-988163-2-4 Published by Freemuse, Nytorv 17, 1450 Copenhagen, Denmark www.freemuse.org Printed by Handy-Print, Denmark © Freemuse, 2008 Layout by Kristina Funkeson Photos courtesy of Anna Schori (p. 26), Ole Reitov (p. 28 & p. 64), Andy Rice (p. 32), Marie Korpe (p. 40) & Mik Aidt (p. 66). The remaining photos are artist press photos. Proofreading by Julian Isherwood Supervision of production by Marie Korpe All rights reserved CONTENTS INTRODUCTION Human rights for musicians – The Freemuse story Marie Korpe 9 Ten years of Freemuse – A view from the chair Martin Cloonan 13 PART I Impressions & Descriptions Deeyah 21 Marcel Khalife 25 Roger Lucey 27 Ferhat Tunç 29 Farhad Darya 31 Gorki Aguila 33 Mahsa Vahdat 35 Stephan Said 37 Salman Ahmad 41 PART II Interactions & Reactions Introducing Freemuse Krister Malm 45 The organisation that was missing Morten -

RAFOC REMINISCENCES and RAMBLINGS - WEEK 62 – 11Th JUNE 2021

ROYAL AIR FORCE OFFICERS’ CLUB Johannesburg P.O. Box 69726 BRYANSTON 2021 [email protected] www.rafoc.org President: David MacKinnon-Little Vice Presidents: Basil Hersov, Colin Francis, Geoff Quick, David Lake Chairman: Bruce Harrison [email protected] Tel: 011 673 0291 Cell: 083 325 0025 Vice Chairman: Jon Adams [email protected] Tel: 011 678 7702 Cell: 082 450 0616 Hon. Secretary: Colin Ackroyd Tel: 012 942 1111 Cell: 082 800 5845 Hon. Treasurer: Jeff Earle Tel: 011 616 3189 Cell: 083 652 1002 Committee Members: Russell Swanborough Tel: 011 884 2611 Cell: 083 263 2740 Karl Jensen Tel: 011 234 0598 Cell: 082 331 4652 Jean-Michel Girard Cell: 083 659 1067 Geoff Fish Tel: 012 667 2759 Cell: 083 660 9697 Web Master: Hanke Fourie Tel: Cell: 082 553 0210 Bank Account: Nedbank - Melrose Arch Br: 19 66 05 Account 19 66 278 063 RAFOC REMINISCENCES AND RAMBLINGS - WEEK 62 – 11th JUNE 2021 GREETINGS: Day 442... More snow on the Berg, extended Eskom load-shedding and water cuts continue in many residential areas... Eskom denies secretly launching stage 6 load-shedding... Ramaphosa places health minister Zweli Mkhize on special leave... Massive increase in criminals trying to steal your identity in South Africa... more than half of all South Africans (36 million) benefitting from government grants in some manner. South Africa’s shrinking tax base is too strained to fund the NHI experts say... Wildlife, bribery and cigarettes part of latest Op Corona successes... Hmm... Rassie upbeat about the 45-man Springbok squad announced for the three-Test series against the British Lions in South Africa. -

Music 10378 Songs, 32.6 Days, 109.89 GB

Page 1 of 297 Music 10378 songs, 32.6 days, 109.89 GB Name Time Album Artist 1 Ma voie lactée 3:12 À ta merci Fishbach 2 Y crois-tu 3:59 À ta merci Fishbach 3 Éternité 3:01 À ta merci Fishbach 4 Un beau langage 3:45 À ta merci Fishbach 5 Un autre que moi 3:04 À ta merci Fishbach 6 Feu 3:36 À ta merci Fishbach 7 On me dit tu 3:40 À ta merci Fishbach 8 Invisible désintégration de l'univers 3:50 À ta merci Fishbach 9 Le château 3:48 À ta merci Fishbach 10 Mortel 3:57 À ta merci Fishbach 11 Le meilleur de la fête 3:33 À ta merci Fishbach 12 À ta merci 2:48 À ta merci Fishbach 13 ’¡¡ÒàËÇèÒ 3:33 à≤ŧ¡ÅèÍÁÅÙ¡ªÒÇÊÂÒÁ ʶҺђÇÔ·ÂÒÈÒʵÃì¡ÒÃàÃÕÂ’… 14 ’¡¢ÁÔé’ 2:29 à≤ŧ¡ÅèÍÁÅÙ¡ªÒÇÊÂÒÁ ʶҺђÇÔ·ÂÒÈÒʵÃì¡ÒÃàÃÕÂ’… 15 ’¡à¢Ò 1:33 à≤ŧ¡ÅèÍÁÅÙ¡ªÒÇÊÂÒÁ ʶҺђÇÔ·ÂÒÈÒʵÃì¡ÒÃàÃÕÂ’… 16 ¢’ÁàªÕ§ÁÒ 1:36 à≤ŧ¡ÅèÍÁÅÙ¡ªÒÇÊÂÒÁ ʶҺђÇÔ·ÂÒÈÒʵÃì¡ÒÃàÃÕÂ’… 17 à¨éÒ’¡¢Ø’·Í§ 2:07 à≤ŧ¡ÅèÍÁÅÙ¡ªÒÇÊÂÒÁ ʶҺђÇÔ·ÂÒÈÒʵÃì¡ÒÃàÃÕÂ’… 18 ’¡àÍÕé§ 2:23 à≤ŧ¡ÅèÍÁÅÙ¡ªÒÇÊÂÒÁ ʶҺђÇÔ·ÂÒÈÒʵÃì¡ÒÃàÃÕÂ’… 19 ’¡¡ÒàËÇèÒ 4:00 à≤ŧ¡ÅèÍÁÅÙ¡ªÒÇÊÂÒÁ ʶҺђÇÔ·ÂÒÈÒʵÃì¡ÒÃàÃÕÂ’… 20 áÁèËÁéÒ¡ÅèÍÁÅÙ¡ 6:49 à≤ŧ¡ÅèÍÁÅÙ¡ªÒÇÊÂÒÁ ʶҺђÇÔ·ÂÒÈÒʵÃì¡ÒÃàÃÕÂ’… 21 áÁèËÁéÒ¡ÅèÍÁÅÙ¡ 6:23 à≤ŧ¡ÅèÍÁÅÙ¡ªÒÇÊÂÒÁ ʶҺђÇÔ·ÂÒÈÒʵÃì¡ÒÃàÃÕÂ’… 22 ¡ÅèÍÁÅÙ¡â€ÃÒª 1:58 à≤ŧ¡ÅèÍÁÅÙ¡ªÒÇÊÂÒÁ ʶҺђÇÔ·ÂÒÈÒʵÃì¡ÒÃàÃÕÂ’… 23 ¡ÅèÍÁÅÙ¡ÅéÒ’’Ò 2:55 à≤ŧ¡ÅèÍÁÅÙ¡ªÒÇÊÂÒÁ ʶҺђÇÔ·ÂÒÈÒʵÃì¡ÒÃàÃÕÂ’… 24 Ë’èÍäÁé 3:21 à≤ŧ¡ÅèÍÁÅÙ¡ªÒÇÊÂÒÁ ʶҺђÇÔ·ÂÒÈÒʵÃì¡ÒÃàÃÕÂ’… 25 ÅÙ¡’éÍÂã’ÍÙè 3:55 à≤ŧ¡ÅèÍÁÅÙ¡ªÒÇÊÂÒÁ ʶҺђÇÔ·ÂÒÈÒʵÃì¡ÒÃàÃÕÂ’… 26 ’¡¡ÒàËÇèÒ 2:10 à≤ŧ¡ÅèÍÁÅÙ¡ªÒÇÊÂÒÁ ʶҺђÇÔ·ÂÒÈÒʵÃì¡ÒÃàÃÕÂ’… 27 ÃÒËÙ≤˨ђ·Ãì 5:24 à≤ŧ¡ÅèÍÁÅÙ¡ªÒÇÊÂÒÁ ʶҺђÇÔ·ÂÒÈÒʵÃì¡ÒÃàÃÕÂ’… -

Interview with Diane Thram by Meredith Holmgren, in Conversation with Diane Thram

Spring 2014 Interview with Diane Thram by Meredith Holmgren, in conversation with Diane Thram The International Library of African Music (ILAM) at Rhodes University in Grahamstown, South Africa, is widely considered to be the oldest and largest repository of African music field recordings in the world. Founded in 1954 by Hugh Tracey as a research institution and archive, it preserves thousands of historical recordings going back to 1929 and continues to support contemporary fieldwork. Among its most renowned recordings is Hugh Tracey’s seminal Sound of Africa series—selections of which are available from Smithsonian Folkways Recordings—which remains among the most influential fieldwork in the field of African ethnomusicology. Smithsonian Folkways Magazine editor Meredith Holmgren corresponded with ILAM’s director Diane Thram about their impressive collections and projects. The following represents an abbreviated, edited version of the conversation. ***** MH: What are the main collections at the International Library of African Music (ILAM)? DT: ILAM’s major holding is the Hugh Tracey collection, but other holdings include the Andrew Tracey collection and Dave Dargie collection... We’ve recently processed Jaco Kruger’s field collection, which includes extensive research on Venda music, from the northern part of South Africa. And [we have] another collection from a sociologist here at Rhodes University [Michael Drewett] who did a lot of research on the censorship of popular music during apartheid. His field recordings are being processed now and digitized. It’s an ongoing thing. We receive deposits from researchers doing work with African music and one of our aims is to build the archive. -

Zimfest 2007 Registration Guide

ZIMBABWEAN MUSIC FESTIVAL Olympia, Washington • August 24 - 26, 2007 GREETINGS! ZIMBABWEAN GUESTS Welcome to the Zimbabwean Music Festival 2007 Our community began when a master musician from Registration Guide. This year’s festival will be held on Zimbabwe, Dumisani Maraire, arrived in Seattle in 1968. August 24, 25, and 26 at South Puget Sound Community Spreading the joy and culture from his homeland, the College (SPSCC) in Olympia, Washington, with Prefest world is now a much richer place than it was before activities on August 23. Olympia is a community rich in he came. Arriving in 1982, Ephat Mujuru was the next World Music, with local groups performing Indonesian Zimbabwean musician to make the United States a place gamelan, Brazilian samba, West African drumming, and to live and teach on a regular basis. From opposite sides Zimbabwean marimba and mbira, as well as many more of the ocean Paul Berliner and Andrew Tracey were also musical traditions. We are very excited to bring Zimfest instrumental in propagating knowledge. It is to these to Olympia and look forward to sharing this wonder- people that we give a moment of recognition for the ful music and culture with friends and fellow musicians work they have started. This work continues through all here! the teachers who visit from Zimbabwe as well as through Many excellent bands and musicians will be perform- those of us who leave home for a while to deepen our- ing in the afternoon and evening concerts. There is no selves in the Shona and Ndebele cultures in Zimbabwe. charge -

Politics and Popular Culture: the Renaissance in Liberian Music, 1970-89

POLITICS AND POPULAR CULTURE: THE RENAISSANCE IN LIBERIAN MUSIC, 1970-89 By TIMOTHY D. NEVIN A DISSERTATION PRESENTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA IN PARTIAL FUFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA 2010 1 © 2010 Timothy Nevin 2 To all the Liberian musicians who died during the war-- (Tecumsey Roberts, Robert Toe, Morris Dorley and many others) Rest in Peace 3 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I would like to thank my parents and my uncle Frank for encouraging me to pursue graduate studies. My father’s dedication to intellectual pursuits and his life-long love of teaching have been constant inspirations to me. I would like to thank my Liberian wife, Debra Doeway for her patience in attempting to answer my thousand and one questions about Liberian social life and the time period “before the war.” I would like to thank Dr. Luise White, my dissertation advisor, for her guidance and intellectual rigor as well as Dr. Sue O’Brien for reading my manuscript and offering helpful suggestions. I would like to thank others who also read portions of my rough draft including Marissa Moorman. I would like to thank University of Florida’s Africana librarians Dan Reboussin and Peter Malanchuk for their kind assistance and instruction during my first semester of graduate school. I would like to acknowledge the many university libraries and public archives that welcomed me during my cross-country research adventure during the summer of 2007. These include, but are not limited to; Verlon Stone and the Liberian Collections Project at Indiana University, John Collins and the University of Ghana at East Legon, Northwestern University, Emory University, Brown University, New York University, the National Archives of Liberia, Dr. -

Downloaded for Personal Non‐Commercial Research Or Study, Without Prior Permission Or Charge

Mhishi, Lennon Chido (2017) Songs of migration : experiences of music, place making and identity negotiation amongst Zimbabweans in London. PhD thesis. SOAS University of London. http://eprints.soas.ac.uk/26684 Copyright © and Moral Rights for this thesis are retained by the author and/or other copyright owners. A copy can be downloaded for personal non‐commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge. This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the copyright holder/s. The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. When referring to this thesis, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given e.g. AUTHOR (year of submission) "Full thesis title", name of the School or Department, PhD Thesis, pagination. Songs of Migration: Experiences of Music, Place Making and Identity Negotiation Amongst Zimbabweans in London Lennon Chido Mhishi Thesis submitted for the degree of PhD Anthropology and Sociology 2017 Department of Anthropology and Sociology SOAS, University of London 1 I have read and understood regulation 17.9 of the Regulations for students of the SOAS, University of London concerning plagiarism. I undertake that all the material presented for examination is my own work and has not been written for me, in whole or in part, by any other person. I also undertake that any quotation or paraphrase from the published or unpublished work of another person has been duly acknowledged in the work which I present for examination.