The Fascinating Story-Telling of Etruscan Mirrors – the Meaning Behind 8LER

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Hellenic Saga Gaia (Earth)

The Hellenic Saga Gaia (Earth) Uranus (Heaven) Oceanus = Tethys Iapetus (Titan) = Clymene Themis Atlas Menoetius Prometheus Epimetheus = Pandora Prometheus • “Prometheus made humans out of earth and water, and he also gave them fire…” (Apollodorus Library 1.7.1) • … “and scatter-brained Epimetheus from the first was a mischief to men who eat bread; for it was he who first took of Zeus the woman, the maiden whom he had formed” (Hesiod Theogony ca. 509) Prometheus and Zeus • Zeus concealed the secret of life • Trick of the meat and fat • Zeus concealed fire • Prometheus stole it and gave it to man • Freidrich H. Fuger, 1751 - 1818 • Zeus ordered the creation of Pandora • Zeus chained Prometheus to a mountain • The accounts here are many and confused Maxfield Parish Prometheus 1919 Prometheus Chained Dirck van Baburen 1594 - 1624 Prometheus Nicolas-Sébastien Adam 1705 - 1778 Frankenstein: The Modern Prometheus • Novel by Mary Shelly • First published in 1818. • The first true Science Fiction novel • Victor Frankenstein is Prometheus • As with the story of Prometheus, the novel asks about cause and effect, and about responsibility. • Is man accountable for his creations? • Is God? • Are there moral, ethical constraints on man’s creative urges? Mary Shelly • “I saw the pale student of unhallowed arts kneeling beside the thing he had put together. I saw the hideous phantasm of a man stretched out, and then, on the working of some powerful engine, show signs of life, and stir with an uneasy, half vital motion. Frightful must it be; for supremely frightful would be the effect of any human endeavour to mock the stupendous mechanism of the Creator of the world” (Introduction to the 1831 edition) Did I request thee, from my clay To mould me man? Did I solicit thee From darkness to promote me? John Milton, Paradise Lost 10. -

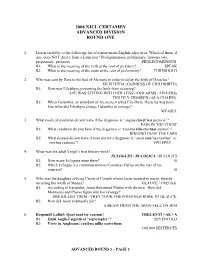

2000 Texas State Certamen -- Round One, Upper Level Tu

2000 TEXAS STATE CERTAMEN -- ROUND ONE, UPPER LEVEL TU #1: What girl, abandoned on Naxos, became the bride of Dionysus? ARIADNE B1: Who had abandoned Ariadne, after she had helped to save his life? THESEUS B2: What sister of Ariadne later married Theseus? PHAEDRA TU#2: Who wrote the Epicurean work De Rerum Natura? LUCRETIUS B1: Of what did Lucretius reputedly die? LOVE POTION B2: What famous Roman prepared De Rerum Natura for publishing after the death of Lucretius? CICERO TU #3: Who was turned into a weasel for tricking Eileithyia into allowing Heracles to be born? GALANTHIS B1: Who was the half-brother of Heracles, and the son of Amphitryon? IPHICLES B2: Who was the nephew of Heracles who helped him to kill the Hydra? IOLAUS TU#4: Whose co-consul was Caesar in 59 B.C.? (CALPURNIUS) BIBULUS B1&2: For five points each, name two of the three provinces Caesar oversaw during his first consulship. ILLYRICUM, GALLIA CISALPINA, GALLIA NARBONENSIS/TRANSALPINA (aka PROVINCIA) TU #5: What type of verb are soleÇ, gaudeÇ, and f§dÇ? SEMI-DEPONENT B1: Say ‘I used to rejoice’ in Latin. GAUDEBAM B2; Say ‘I have rejoiced’ in Latin. GAV¦SUS/-A SUM TU#6: Although they were called the Aloadae, Otus and Ephialtes were really the sons of which god? POSEIDON B1: How did the mother of the Aloadae attract Poseidon? STOOD IN THE SEA AND SPLASHED WATER ON HERSELF UNTIL HE IMPREGNATED HER B2: What deity tricked Otus and Ephialtes into killing each other? ARTEMIS TU #7: What was the dinner held on the ninth day after a death called? CENA NOVENDIALIS B1: What was the minimum burial for religious purposes? THREE HANDFULS OF DIRT B2: What was a cenotaphium? A TOMB ERECTED IF THE BODY COULD NOT BE RECOVERED (AN EMPTY TOMB) TU#8: Who called his work nugae? CATULLUS B1: To what fellow author did he dedicate them? CORNELIUS NEPOS B2: Catullus was most famous for his love poetry to what lady? LESBIA/CLODIA TU #9: Romulus and Remus were brothers, but what is the meaning of the Latin word remus? OAR B1: With this in mind, what is a remex? ROWER/OARSMAN B2: Define remigÇ. -

Herakles Iconography on Tyrrhenian Amphorae

HERAKLES ICONOGRAPHY ON TYRRHENIAN AMPHORAE _____________________________________________ A Thesis presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School University of Missouri-Columbia _____________________________________________ In Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts ______________________________________________ by MEGAN LYNNE THOMSEN Dr. Susan Langdon, Thesis Supervisor DECEMBER 2005 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank my thesis advisor, Dr. Susan Langdon, and the other members of my committee, Dr. Marcus Rautman and Dr. David Schenker, for their help during this process. Also, thanks must be given to my family and friends who were a constant support and listening ear this past year. ii TABLE OF CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS………………………………………………………………ii LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS……………………………………………………………..v Chapter 1. TYRRHENIAN AMPHORAE—A BRIEF STUDY…..……………………....1 Early Studies Characteristics of Decoration on Tyrrhenian Amphorae Attribution Studies: Identifying Painters and Workshops Market Considerations Recent Scholarship The Present Study 2. HERAKLES ON TYRRHENIAN AMPHORAE………………………….…30 Herakles in Vase-Painting Herakles and the Amazons Herakles, Nessos and Deianeira Other Myths of Herakles Etruscan Imitators and Contemporary Vase-Painting 3. HERAKLES AND THE FUNERARY CONTEXT………………………..…48 Herakles in Etruria Etruscan Concepts of Death and the Underworld Etruscan Funerary Banquets and Games 4. CONCLUSION………………………………………………………………..67 iii APPENDIX: Herakles Myths on Tyrrhenian Amphorae……………………………...…72 BIBLIOGRAPHY………………………………………………………………………..77 ILLUSTRATIONS………………………………………………………………………82 iv LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS Figure Page 1. Tyrrhenian Amphora by Guglielmi Painter. Bloomington, IUAM 73.6. Herakles fights Nessos (Side A), Four youths on horseback (Side B). Photos taken by Megan Thomsen 82 2. Tyrrhenian Amphora (Beazley #310039) by Fallow Deer Painter. Munich, Antikensammlungen 1428. Photo CVA, MUNICH, MUSEUM ANTIKER KLEINKUNST 7, PL. 322.3 83 3. Tyrrhenian Amphora (Beazley #310045) by Timiades Painter (name vase). -

2019 HSC English Extension 2 Sample 1

Band 3/4 2019 HSC English Extension 2 Sample 1 Annotation: This is a clever, substantial and sustained postmodern Short Fiction reflecting on recent political events. Writing through a feminist lens it uses mythological tales and appropriates these to engage the audience with the ideas offered in the Major Work. It uses a variety of different forms, reflecting on the ways events are reported across traditional forms and emerging forms of social media. It is coherent and confident with well-developed skills in articulating and reflecting on the process of investigation. NOTE: All redacted quotes are awaiting copyright approval Band 3/4 2019 HSC English Extension 2 Sample 1 The Royal Commission into the Misconduct of Zeus MEDIA RELEASE PuBlished January 2020 The Royal Commission into the Misconduct of Zeus has announced that hearings will commence in April 2020, to Be held internationally in multiple secure and private locations. The Commission is inviting suBmissions for any information aBout the misconduct of Zeus, the King of Gods. Those wishing to make a suBmission will have until 31 March 2020. Zeus currently resides in Mount Olympus with other gods and goddesses, as he has done for millennia, and has Been made aware of the future investigation. The Commission has sought an agreement from the gods and goddesses that there will Be no godly interference with witnesses. For further information contact the Commission via the weBsite or directly By email [email protected]. NOTE: All redacted quotes are awaiting copyright approval Zeus @RealKingofGods The RC has hit a new low. Supporters of Mount Olympus showed up in THOUSANDS across the world. -

THE ARGONAUTIKA He'd Gone on His Vain Quest with Peirithoos: That Couple Would Have Made Their Task's Fulfillment Far Easier for Them All

Book I Starting from you, Phoibos, the deeds ofthose old-time mortals I shall relute, who by way ofthe Black Sea's mouth and through the cobalt-dark rocks, at King Pelias 's commandment, in search of the Golden Fleece drove tight-thwarted Argo. For Pelias heard it voiced that in time thereafter a grim fate would await him, death at the prompting of the man he saw come, one-sandaled, from folk in the country: and not much later-in accordance with your word-Jason, fording on foot the Anauros's wintry waters, saved from the mud one sandal, but left the other stuck fast in the flooded estuary, pressed straight on to have his share in the sacred feast that Pelias was preparing for Poseidon his father, and the rest of the gods, though paying no heed to Pelasgian Hera. The moment Pelias saw him, he knew, and devised him a trial of most perilous seamanship, that in deep waters or away among foreign folk he might lose his homecoming. ,\row singers before 7ny time have recounted how the vessel was fashioned 4 Argos with the guidance of Athena. IW~cctIplan to do now is tell the name and farnib of each hero, describe their long voyage, all they accomplished in their wanderings: may the Muses inspire mnj sinpng! First in our record be Orpheus, whom famous Kalliope, after bedding Thracian Oikgros, bore, they tell us, 44 THE XRGONAUTIKA hard by Pimpleia's high rocky lookout: Orpheus, who's said to have charmed unshiftable upland boulders and the flow of rivers with the sound of his music. -

2008 Njcl Certamen Advanced Division Round One

2008 NJCL CERTAMEN ADVANCED DIVISION ROUND ONE 1. Listen carefully to the following list of synonymous English adjectives. Which of them, if any, does NOT derive from a Latin root? Prolegomenous, preliminary, introductory, preparatory, prefatory PROLEGOMENOUS B1: What is the meaning of the verb at the root of prefatory? SPEAK B2: What is the meaning of the noun at the root of preliminary? THRESHOLD 2. Who was sent by Hera to the bed of Alcmene in order to delay the birth of Heracles? EILEITHYIA (GODDESS OF CHILDBIRTH) B1: How was Eileithyia preventing the birth from occuring? SHE WAS SITTING WITH HER LEGS (AND ARMS / FINGERS) TIGHTLY CROSSED (AS A CHARM). B2: When Galanthis, an attendant of Alcmene, tricked Eileithyia, Heracles was born. Into what did Eileithyia change Galanthis in revenge? WEASEL 3. What medical condition do you have if the diagnosis is “angina (ăn-jī΄nƏ) pectoris”? PAIN IN THE CHEST B1: What condition do you have if the diagnosis is “tinnitus (tĭn-eye-tus) aurium”? RINGING IN/OF THE EARS B2: What disease do you have if your doctor’s diagnosis is “sacer (săs΄Ər) morbus” or “morbus caducus”? EPILEPSY 4. What was the adult Vergil’s first literary work? ECLOGUES / BUCOLICA / BUCOLICS B1: How many Eclogues were there? 10 B2: Which Eclogue is a commiseration to Cornelius Gallus on the loss of his mistress? 10 5. Who was the daughter of King Creon of Corinth whom Jason wanted to marry, thereby incurring the wrath of Medea? GLAUCE / CREUSA B1: According to Euripides, Jason threatened Medea with divorce. How did Mermerus and Pheres figure into her revenge? SHE KILLED THEM / THEY TOOK THE POISONED ROBE TO GLAUCE. -

Argonautika Entire First Folio

First Folio Teacher Curriculum Guide ARGONAUTIKA adapted and directed by Mary Zimmerman based on the story by Apollonius of Rhodes January 15 to March 2, 2008 First Folio Teacher Curriculum Guide Table of Contents Page Number Welcome to the Shakespeare Theatre Company’s production of Argonautika! About Greek Theatre Brief History of the Audience………………………...1 This season, the Shakespeare Theatre Company The History of Greek Drama……………..……………3 presents eight plays by William Shakespeare and On Greek Society and Culture……………………….5 other classic playwrights. The mission of all About the Authors …………………………...……………6 Education Department programs is to deepen understanding, appreciation and connection to About the Play classic theatre in learners of all ages. One Synopsis of Argonautika……………..…………………7 approach is the publication of First Folio Teacher Curriculum Guides. The Myth Behind the Play ..…………………………..8 The Hero’s Quest…..………………………………………..9 For the 2007-08 season, the Education Fate and Free Will…...………………..………..………..10 Department will publish First Folio Teacher Mythology: More than just a good story…...11 Curriculum Guides for our productions of Glossary of Terms and Characters..…………….12 Tamburlaine, Taming of the Shrew, Argonautika Questing…………………………………………………..…….14 and Julius Caesar. First Folio Guides provide information and activities to help students form Classroom Connections a personal connection to the play before • Before the Performance……………………………15 attending the production at the Shakespeare Journey Game Theatre Company. First Folio Guides contain God and Man material about the playwrights, their world and It’s Greek to Me the plays they penned. Also included are The Hero’s Journey approaches to explore the plays and productions in the classroom before and after (Re)Telling Stories the performance. -

View / Download 2.4 Mb

Lucian and the Atticists: A Barbarian at the Gates by David William Frierson Stifler Department of Classical Studies Duke University Date:_______________________ Approved: ___________________________ William A. Johnson, Supervisor ___________________________ Janet Downie ___________________________ Joshua D. Sosin ___________________________ Jed W. Atkins Dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Classical Studies in the Graduate School of Duke University 2019 ABSTRACT Lucian and the Atticists: A Barbarian at the Gates by David William Frierson Stifler Department of Classical Studies Duke University Date:_______________________ Approved: ___________________________ William A. Johnson, Supervisor ___________________________ Janet Downie ___________________________ Joshua D. Sosin ___________________________ Jed W. Atkins An abstract of a dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Classical Studies in the Graduate School of Duke University 2019 Copyright by David William Frierson Stifler 2019 Abstract This dissertation investigates ancient language ideologies constructed by Greek and Latin writers of the second and third centuries CE, a loosely-connected movement now generally referred to the Second Sophistic. It focuses on Lucian of Samosata, a Syrian “barbarian” writer of satire and parody in Greek, and especially on his works that engage with language-oriented topics of contemporary relevance to his era. The term “language ideologies”, as it is used in studies of sociolinguistics, refers to beliefs and practices about language as they function within the social context of a particular culture or set of cultures; prescriptive grammar, for example, is a broad and rather common example. The surge in Greek (and some Latin) literary output in the Second Sophistic led many writers, with Lucian an especially noteworthy example, to express a variety of ideologies regarding the form and use of language. -

Portal to Symbolism

PORTAL TO SYMBOLISM So far we’ve seen symbolism with the different mythologies and how the gods and goddesses were associated with certain symbols. A symbol is something that represents something other than itself. For example, snakes may be symbolic of rebirth, because they shed their skin. The Harry Potter books are rich with symbolism of all kinds—animals, numbers, colors, and the wood used for wands all have symbolic meanings. J.K. Rowling may not always have meant to give a certain animal symbolic or mythological meanings, but we can find them there anyway. In This Section we'll Learn About: • Animal Symbolism • Number Symbolism • Color Symbolism • Wood Symbolism Harry Potter Animal Symbolism Are you a dog person or a cat person? We often ask people this question, because it is an indication of the person's personality. We attribute certain qualities to a "cat person" that are different from those of a "dog person." This goes back to ancient times when people would give symbolic meaning to certain animals because a god or goddess was associated with that animal. If an animal was associated with a goddess (like the hare) then that animal became symbolic of more feminine qualities. Obviously masculine animals (like the stag) became associated with more manly qualities. The kinds of gods and goddesses mattered too—was it a sky god or an earth god? A sky god had a different kind of animal as a symbol than an earth god or sea god. The 1 symbolism might also be something as simple as where the animal lives or how it moves. -

The Twelve Labors of Herakles

The Getty Teacher Resource Villa The Twelve Labors of Herakles Herakles was a universal hero, celebrated by the Greeks, the Etruscans (who called him Hercle), and the Romans (who knew him as 1. The Lion Hercules). He was the son of Zeus (king of the of Nemea gods) and a mortal woman, Alkmene. Ironically, his name means “the glory” (kleos) of Hera (queen of the gods), his jealous stepmother, who drove him mad and caused him to kill his wife and children. As penance, the hero was bound to serve King Eurystheus of Mycenae and Tiryns. The king sent him on a series of The Lion of Nemea had an impervious hide difficult tasks, or labors, twelve of which and could not be killed with traditional weapons. Herakles strangled it and then became standardized in art and literature. used its own claw to skin it. Afterward he wore its pelt as a talisman. 2. The Hydra of Lerna 3. The Hind of Keryneia The Hydra of Lerna was a serpentlike, multiheaded monster. Every time a head was cut off, two more grew in its place. With the aid of his nephew Education Iolaos,Educ Heraklesation killed the beast by cauterizing each wounded neck with a torch. 6/8 point The J. Paul Getty Museum The J. Paul Getty Museum at the Getty Center The Hind of Keryneia was sacred to Artemis ducation (goddess of the hunt and wild animals). Herakles E was ordered to bring the deer, or its golden The J. Paul Getty Museum horn, back to Eurystheus without harming it. -

Generosa Sangco-Jackson Agon Round NJCL 2014.Pdf

NJCL Ἀγών 2014 Round 1 1. What Athenian archon was responsible for passing the seisachtheia, outlawing enslavement to pay off debt? SOLON B1: In what year was Solon elected archon? 594 B.C. B2: Name one of the two political parties that formed after Solon’s reforms. THE COAST / THE PLAIN 2. What is the meaning of the Greek noun θάλαττα? SEA B1: Change θάλαττα to the genitive singular. θαλάττης B2: Change θαλάττης to the accusative singular. θάλατταν 3. "Sing, muse, the wrath of Achilles" is the first line of what work of Greek literature? ILIAD B1: Into how many books is the Iliad divided? 24 B2: In which book of Homer's Iliad does the archer Pandarus break the truce between the Greeks and Trojans? BOOK 4 4. What is the meaning of the Greek adjective from which "sophisticated" is derived? WISE, SKILLED (σοφός) B1: What derivative of σοφός is an oxymoronic word meaning “wise fool”? SOPHOMORE B2: What derivative of σοφός applies to a person who reasons with clever but fallacious arguments, particularly with a disregard to the truth. SOPHIST 5. What hunter in mythology was blinded by king Oenopion on Chios for drunkenly violating his daughter Merope? ORION B1: When Orion regained his sight and returned to Chios for revenge, how did the king save himself from Orion’s murderous intentions? HE HID IN AN UNDERGROUND CHAMBER B2: Which of the Olympians had fashioned this chamber? HEPHAESTUS 6. What king of Pylos, known as the Gerenian charioteer, was renown for his wisdom during the Trojan war? NESTOR B1: Who was Nestor’s father, who demanded Phylacus’ cattle as the bride-price for his daughter Pero? NELEUS B2: What young son of Amythaon and Idomene eventually offered up the bride- price and married Pero? BIAS 7. -

Sisyphos 1 Sisyphos

Sisyphos 1 Sisyphos Sisyphos (griechisch Σίσυφος, latinisiert Sisyphus) ist ein Held der griechischen Mythologie. Er ist der Sohn von Aeolos und Enarete. Er war der Gatte von Merope und zeugte mit ihr den Glaukos, Ornytion, Thersandros und Almos. Er gilt als der Stifter der Isthmischen Spiele und Gründer und König von Ephyra (Korinth). Nach anderer Überlieferung war er nicht der Gründer von Ephyra, sondern erhielt die Herrschaft von Medea übertragen. Vor allem ist er im Volksmund bekannt durch seine Bestrafung, die sogenannte Sisyphusarbeit. Mythos Stiftung der Isthmischen Spiele durch Sisyphos Persephone beaufsichtigt Sisyphos in der Unterwelt, schwarzfigurige attische Amphora, um 530 v. Chr., Staatliche Antikensammlungen (Inv. 1494) Ino hatte im Wahn Melikertes, ihren eigenen Sohn, getötet und sich mit dem Leichnam ins Meer gestürzt, als sie wieder zu Sinnen kam. Ein Delphin brachte den Knaben an Land. Sisyphos fand ihn und begrub ihn auf dem Isthmus und stiftete ihm zu Ehren die Isthmischen Spiele. (Am angegebenen Ort wird Theseus beziehungsweise Poseidon als Stifter genannt.) Sisyphos' Versuch, seinen Bruder Salmoneus zu töten Sisyphos befragte das Orakel von Delphi, wie er seinen Bruder Salmoneus töten könne. Darauf erhielt er die Antwort, dass er Kinder mit Tyro, der Tochter des Salmoneus, zeugen solle. Diese würden dann Salmoneus töten. Er ließ sich mit Tyro ein, und diese schenkte zwei Söhnen das Leben. Als sie jedoch von dem Orakel hörte, tötete sie ihre eigenen Kinder. Zeugung des Odysseus Autolykos stahl heimlich Rinder, Schafe und Ziegen des Sisyphos. Sisyphos bemerkte, dass seine Herden kleiner wurden, während die des Autolykos weiter zunahmen. Er markierte seine Tiere an den Hufen und konnte so den Diebstahl nachweisen.