Relationship of Trust Between Confessor and Confessant

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

To Pray Again As a Catholic: the Renewal of Catholicism in Western Ukraine

To Pray Again as a Catholic: The Renewal of Catholicism in Western Ukraine Stella Hryniuk History and Ukrainian Studies University of Manitoba October 1991 Working Paper 92-5 © 1997 by the Center for Austrian Studies. Permission to reproduce must generally be obtained from the Center for Austrian Studies. Copying is permitted in accordance with the fair use guidelines of the US Copyright Act of 1976. The the Center for Austrian Studies permits the following additional educational uses without permission or payment of fees: academic libraries may place copies of the Center's Working Papers on reserve (in multiple photocopied or electronically retrievable form) for students enrolled in specific courses: teachers may reproduce or have reproduced multiple copies (in photocopied or electronic form) for students in their courses. Those wishing to reproduce Center for Austrian Studies Working Papers for any other purpose (general distribution, advertising or promotion, creating new collective works, resale, etc.) must obtain permission from the Center. The origins of the Ukrainian Catholic Church lie in the time when much of present-day Ukraine formed part of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth. It was then, in 1596, that for a variety of reasons, many of the Orthodox bishops of the region decided to accept communion with Rome.(1) After almost four hundred years the resulting Union of Brest remains a contentious subject.(2) The new "Uniate" Church formally recognized the Pope as Head of the Church, but maintained its traditional Byzantine or eastern rite, calendar, its right to ordain married men as priests, and its right to elect its own bishops. -

THE CONFESSOR's AUTHORITY the Catholic Church Meets

CHAPTER THREE THE CONFESSOR'S AUTHORITY The Catholic Church meets people's need for authority and abso lution with its doctrine on the penance sacrament and its teaching that the priest possesses divine qualities to administer the sacrament and exercise moral authority. During the ceremony of ordination, God Himself has made a priest the instrument of His power in this world. Thus, the priest is endowed with a character indelebilis which distinguishes him from all secular persons and qualifies him to carry out his mission as intercessor between God and Man, indeed even to deputize for God among mortals. A Catholic writer has said that the priest shows his extraordinary qualities as director of souls by his "apostolic zeal, knowledge of God's ways and supernatural wisdom". 1 But those gifts are not enough for a priest when he officiates in the penance sacrament. They could have their effect also outside that sacrament. As administrator of the sacrament he possesses a special and divine instinct: this shows him the way when he instructs penitents on remedies for their sins and gives them guidance on their future conduct. 2 Such an image of the priest's high office is inculcated in Catholics by their creed itself. A good Catholic accepts a priest's authority; consequently he is prepared in advance to follow confessional advice and to comply in all matters with directions as to his way of life. 3 This maintenance of clerical authority has an integral place in the structure of Roman Catholic doctrine. It is connected there both with the concept of the Church as a whole and with teaching on the sacraments. -

Saint Maximus the Confessor and His Defense of Papal Primacy

Love that unites and vanishes: Saint Maximus the Confessor and his defense of papal primacy Author: Jason C. LaLonde Persistent link: http://hdl.handle.net/2345/bc-ir:108614 This work is posted on eScholarship@BC, Boston College University Libraries. Boston College Electronic Thesis or Dissertation, 2019 Copyright is held by the author, with all rights reserved, unless otherwise noted. Love that Unites and Vanishes: Saint Maximus the Confessor and his Defense of Papal Primacy Thesis for the Completion of the Licentiate in Sacred Theology Boston College School of Theology and Ministry Fr. Jason C. LaLonde, S.J. Readers: Fr. Brian Dunkle, S.J., BC-STM Dr. Adrian Walker, Catholic University of America May 3, 2019 2 Introduction 3 Chapter One: Maximus’s Palestinian Provenance: Overcoming the Myth of the Greek Life 10 Chapter Two: From Monoenergism to Monotheletism: The Role of Honorius 32 Chapter Three: Maximus on Roman Primacy and his Defense of Honorius 48 Conclusion 80 Appendix – Translation of Opusculum 20 85 Bibliography 100 3 Introduction The current research project stems from my work in the course “Latin West, Greek East,” taught by Fr. Brian Dunkle, S.J., at the Boston College School of Theology and Ministry in the fall semester of 2016. For that course, I translated a letter of Saint Maximus the Confessor (580- 662) that is found among his works known collectively as the Opuscula theologica et polemica.1 My immediate interest in the text was Maximus’s treatment of the twin heresies of monoenergism and monotheletism. As I made progress -

CONFESSIONAL METHOD the Confessor's Ability to Inspire

CHAPTER FIVE CONFESSIONAL METHOD The confessor's ability to inspire confidence is evidently connected with the method he uses for confession and spiritual guidance. It is clear, too, that a confessor endowed with special personal qualifi cations will create a confessional method worth following. He does so sua sponte, without reflecting closely on his course of action. Later, however, he may derive a system with clearly framed rules from his experience. We might study the methods of some prominent confes sors, basing our examination either on clear and systematic state ments, when such exist, or on what may be deduced from how those confessors practised : this should supply us with more information than can be gleaned by merely directing our attention at the confes sor's personal virtues or "intuitive capacity". One of the great figures in the Catholic cure of souls is-as we have already stressed-Fran9ois de Sales. We ought to find that such an exemplary confessor had an ideal method for confession in its Catholic form. His ideas about spiritual healing are still valid and have a normalizing importance in the Catholic Church.1_ By examining his method we should consequently make a somewhat closer approach to how he could get his penitents to rely so completely on his direction -in, for example, such cases as those of Jean-Pierre Camus and Madame de Chantal. The basic principle of Saint Fran9ois' spiritual leadership is, we perceive, that the confessor should not force orders and regulations on the penitent. Fran9ois de Sales assumes that his penitent has a strong desire to attain moral perfection, a desire which should be supported by the confessor's instructions. -

Year of Preparation Primer

YEAR OF PREPARATION PRIMER AN EXPLANATION OF THE ORDER, ITS HISTORY, ITS MEMBERSHIP & THE AMERICAN ASSOCIATION Sovereign Military Order of St. John of Jerusalem, of Rhodes and of Malta American Association 1011 First Avenue New York, NY 10022 Table of Contents Chapter 1 What is the Order of Malta Page 1 Chapter 2 The Year of Preparation Page 7 Chapter 3 The American Association Page 11 Chapter 4 Works and Ministries Page 15 Chapter 5 The Lourdes Pilgrimage Page 22 Chapter 6 A History of the Order of Malta Page 29 Chapter 7 The Daily Prayer of the Order Page 33 Chapter 8 Members of the Order: Knights Page 36 and Dames of Magistral Grace, Those in Obedience and the Professed. Appendix Our Lady of Philermo Page 44 Order of Malta American Association Year of Preparation Formation Program Chapter 1--What is the Order of Malta? This booklet is designed to give you a better understanding of the Order of Malta. With background knowledge of the Order of Malta, you will be in a better position to satisfactorily complete your year- long journey of preparation to become a member of the Order. Hopefully, many of your questions about the Order will be answered in the coming pages. The Order of Malta is a lay religious Order of the Catholic Church with 14,000 members and 80,000 volunteers across the world headed by a Grand Master who governs the Order from Rome, both as a sovereign and as a religious leader. The Order was founded over 900 years ago by Blessed Gerard, a monk and Knight, who gathered a group of men and women together to commit themselves to the assistance of the poor and the sick, and to defend and to give witness to the Catholic faith. -

St. Edward the Confessor Third Sunday of Easter

April 26, 2020 The Roman Catholic Community St. Edward the Confessor Third Sunday of Easter Pastor: Rev. Patrick J. Butler Deacons: Walter MacKinnon & Rit DiCaprio Parish Secretary: Beverly Breen x221 Associate for Pastoral Care: Mary Ann Sekellick x224 Director of Music: Mary Jo Brue x223 Director of Faith Formaon & Youth Ministry: Eddie Treviño x237 Pre-K - 5th Grade Coordinator: Noreen Hayden x233 6th - 10th Grade Coordinator: Sue Carbone x234 Office Hours: Monday - Thursday: 9:00 a.m. - 4:00 p.m. Friday: 9:00 a.m. - 12:00 p.m. Saturday: 4:00 PM (Sacrament of Reconciliaon at 3:00 p.m. or by appointment) Saturday Spanish Mass: 6:30 p.m. Sunday: 7:30, 9:00, & 11:00 AM Weekdays (No Mass on Thursday): 9:00 a.m. 569 Cli on Park Ctr Rd Cli on Park, NY 12065 (518) 371-7372 www.stedwardsny.org ST. EDWARD THE CONFESSOR, CLIFTON PARK PARISH NEWS PARISH NEWS 4PM SATURDAYS – CHANGED TIME FOR LIVE STREAM MASS!!!! We will continue to LIVE STREAM ST. EDWARD’S weekend Mass. We are now celebrating Mass at 4PM on Saturday instead of Sunday. Please go to our parish website and click on the link. (You PLEASE HELP US THANK OUR can also replay the Mass any time!!!) We will also have an Hour of Prayer and Meditation live FIRST RESPONDERS! streamed each Wednesday night at 6:00. We encourage you to view our stream through YouTube and take a few LETTERS: minutes in this hard and stressful time to pray and meditate. In order to thank some of the many people who are working on THE PARISH OFFICES ARE CLOSED, the front lines, we invite you and your children (of all ages!) to BUT WE ARE STILL WORKING!!! All write a letter of thanks to one or more of the following groups: staff are working remotely from home and Medical personnel - doctors, nurses, hospital staff, can be contacted with questions or who are fighting every day to save lives further information. -

St. Edward the Confessor Parish P. O. Box 8866 – 21 Brush Hill Road New Fairfield, CT 06812 (203) 746-2200 Fax (203) 746-4856

St. Edward the Confessor Parish P. O. Box 8866 – 21 Brush Hill Road New Fairfield, CT 06812 (203) 746-2200 Fax (203) 746-4856 Pre-Cana in Saint Edward the Confessor Parish 2013 Congratulations! May God’s fullest blessings be with you during this time as you prepare for your wedding day and your married life. The priests and parish staff of St. Edward are here to assist you so that this time of preparation is as spiritually fruitful for you as possible. Legal Preparation for Marriage 1. In the State of Connecticut you may obtain your marriage license from the town clerk where the marriage will occur or from the town clerk in the Connecticut town where one of the parties to be married resides. 2. Blood tests are no longer needed for the application for a Marriage License. The couple should plan to apply for their license in an adequate time before the wedding. The marriage license is good for 65 days. When you have received the license, bring it to the Parish Office. 3. There are also records which you must obtain for the Church: A. Each Catholic must have a recently issued Baptismal Certificate (no more than six months old). If one of you is Protestant, a Baptismal Certificate is desired if possible. B. Each Catholic must also have a certificate of First Communion and Confirmation if reception of these sacraments is not noted on the Baptismal Certificate. 4. How to obtain the church certificates: A. If any of these sacraments were received at St. Edward, we have your records on file so certificates are not needed. -

Akathist to St. Tikhon of Moscow, Enlightener of North America

Akathist Hymn to St. Tikhon, Patriarch of Moscow Akathist Hymn to St. Tikhon, Patriarch of Moscow Benediction…Amen…O Heavenly King... (Sung)…Trisagion…Psalm 50 Kontakion 1 To you, the steadfast champion of the Holy Orthodox Faith, do we, your spiritual children, offer hymns of praise and thanksgiving, mindful of the many benefactions you have bestowed on us. As you have great boldness before the throne of the Most High, pray earnestly in behalf of all who truly honor your holy memory and cry out to you with love: Rejoice, O humble Tikhon, steadfast confessor of the Faith // and fervent intercessor for our souls! Ikos 1 Called by God to His holy priesthood from your mother's womb, for all the faithful you were an example in word, conduct, love, spirit, faith and purity. You fought well the good fight, and finished difficult course of your life, and kept the Faith, in nowise failing to hold fast to your vows. Wherefore, full of gratitude for your love and sacrifice, we say: Rejoice, you who preached the word of God with fervor; Rejoice, you who were watchful in all things! Rejoice, who made full proof of your ministry; Rejoice, you who as an evangelist proclaimed the glad tidings of salvation! Rejoice, you who reproved those who rejected the truth of the Christian Faith; Rejoice, you who rebuked those who embraced the modern fables of materialism and progress! 1 Rejoice, you who, when the time of your departure was at hand, made provision for the Church; Rejoice, you who have therefore received from God a twofold crown for your righteousness -

The Last Confession by Roger Crane

THE LAST CONFESSION BY ROGER CRANE DRAMATISTS PLAY SERVICE INC. THE LAST CONFESSION Copyright © 2014, Roger Crane All Rights Reserved CAUTION: Professionals and amateurs are hereby warned that performance of THE LAST CONFESSION is subject to payment of a royalty. It is fully protected under the copyright laws of the United States of America, and of all countries covered by the International Copyright Union (including the Dominion of Canada and the rest of the British Commonwealth), and of all countries covered by the Pan- American Copyright Convention, the Universal Copyright Convention, the Berne Convention, and of all countries with which the United States has reciprocal copyright relations. All rights, including without limitation professional/amateur stage rights, motion picture, recitation, lecturing, public reading, radio broadcasting, television, video or sound recording, all other forms of mechanical, electronic and digital reproduction, transmission and distribution, such as CD, DVD, the Internet, private and file-sharing networks, information storage and retrieval systems, photocopying, and the rights of translation into foreign languages are strictly reserved. Particular emphasis is placed upon the matter of readings, permission for which must be secured from the Author’s agent in writing. The English language stock and amateur stage performance rights in the United States, its territories, possessions and Canada for THE LAST CONFESSION are controlled exclusively by DRAMATISTS PLAY SERVICE, INC., 440 Park Avenue South, New York, NY 10016. No professional or nonprofessional performance of the Play may be given without obtaining in advance the written permission of DRAMATISTS PLAY SERVICE, INC., and paying the requisite fee. Inquiries concerning all other rights should be addressed to Alan Brodie Representation, Paddock Suite, The Courtyard, 55 Charterhouse Street, London EC1M 6HA, England. -

160807 Confessor's Tongue 7 Pent

The Confessor’s Tongue for August 7, A. D. 2016 th 7 Sunday after Pentecost, Postfeast of Transfiguration, St. Dometius In honor of St. Maximus the Confessor, whose tongue and right hand were cut off in an attempt by compromising authorities to silence his uncompromising confession of Christ’s full humanity & divinity. Le The Bishop’s Ministry encourage you to read this letter, easily found online During his visit, Bishop Alexander described the or within A Psalter for Prayer published by Holy ministry of the bishop as threefold. Trinity Publications in Jordanville, New York. We First, he shepherds the priests as the priests will only briefly draw out St. Athanasius’ points. shepherd the flock. While the priest is on the However, it would be most beneficial for one to read frontline, the bishop is typically back behind the this letter in order to attend to the specifics of lines, supporting those under fire. The shepherds Athanasius’ insights and suggestions. need support, instruction, direction, prayer, counsel, St. Athanasius affirms the basic truth that all and correction—and this the bishop provides. Scripture is inspired by God [2 Tim 3:16] but believes Second, the bishop serves as an icon of the glory that the Psalter bears special fruit. Each book of the of God when he serves the hierarchical liturgy. Some Bible has its own particular message. We hear of people react negatively to all the ritual and finery, creation in one, about the exodus of Israel in another, objecting that such honor should not be paid to a the Tabernacle and the priesthood, etc. -

Download Download

Early Modern Women: An Interdiciplinary Journal 2006, vol. 1 Maladies up Her Sleeve? Clerical Interpretation of a Suffering Female Body in Counter-Reformation Spain1 Susan Laningham n the second Sunday of Lent in 1598, just as she was about to take Othe holy wafer of communion in the convent of Santa Ana in Ávila, Spain, a thirty-seven-year-old Cistercian nun named María Vela found she could not open her mouth.2 Shocked witnesses reported that María’s jaws were clenched “as if they were nailed,” and no one could wrench them apart. Over the next year, María’s mysterious ailment occurred intermit- tently, sometimes only on Monday, Wednesday, and Friday. The Cisterican sisters would rush early to her room on those mornings, hoping to get her to eat before the malady reappeared, only to find her teeth already clamped shut.3 Complicating the situation was a host of other inexplicable physical ailments: a distended abdomen that arched her spine to the breaking point, hands knotted in a vice-like grip,4 violent tremors, and raging fevers. There were also the illnesses that normally plagued María: spasms in her joints, fluid in her lungs, vertigo, and seizures that some attributed to epilepsy. Accommodations were made for her, not simply because she ailed or came from a distinguished Spanish family,5 but because she claimed that heav- enly visions and voices had revealed to her that all her excruciating pains were sent from God. Since many of her illnesses defied diagnosis, she was fast becoming a topic of unremitting gossip inside and outside the convent walls. -

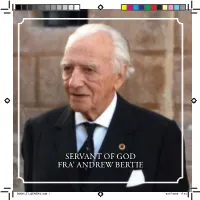

Servant of God Fra' Andrew Bertie

SERVANT OF GOD FRA’ ANDREW BERTIE A BOOKLET_GENERIC.indd 1 02/07/2020 15:34 © BASMOM 2020 Email: [email protected] website: www.orderofmalta.org.uk Registered Charity No. 1103567 (England & Wales) Registered Charity No. SCO 040124 (Scotland) Company No. 05039938 B BOOKLET_GENERIC.indd 2 02/07/2020 15:34 CONTENTS Introduction ....................................................... 3 Election as 78th Grand Master ........................... 5 Works as Grand Master ...................................... 7 Spirituality ......................................................... 9 Early years ........................................................ 11 Works for the Order of Malta ........................... 11 Death of Fra’ Andrew Bertie ............................. 17 The path to sainthood ..................................... 19 Prayers of intercession ...................................... 23 1 BOOKLET_GENERIC.indd 1 02/07/2020 15:34 A current and a future Grand Master: Fra’ Andrew Bertie with Fra’Giacomo Dalla Torre del Tempio di Sanguinetto 2 BOOKLET_GENERIC.indd 2 02/07/2020 15:34 INTRODUCTION Fra’ Andrew Bertie, 78th Grand Master of the Sovereign Order of Malta, was a deeply respected and revered figure, by the 13,500 members of the Order worldwide, by the Church, and by all with whom he came into contact. His vocation, as a Professed Knight of the Order, was to care for the poor and the sick, and to demonstrate this inspiration through his deep Christian spirituality. He lived modestly, with humility and with intense faith.