Download Download

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Making of an Evangelical Tory: the Seventh Earl of Shaftesbury (1801-1885) and the Evolving Character of Victorian Evangelicalism

The Making of an Evangelical Tory: The Seventh Earl of Shaftesbury (1801-1885) and the Evolving Character of Victorian Evangelicalism David Andrew Barton Furse-Roberts A thesis in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy UNSW School of Humanities & Languages Faculty of Arts & Social Sciences November 2015 CONTENTS Page Abstract i Abbreviations ii Acknowledgements iii Introduction I Part I: Locating Anthony Ashley Cooper within the Anglican Evangelical tradition 1 1.1 Ashley’s expression of Evangelicalism 2 1.2 How the associations and leaders of Anglican Evangelicalism shaped the evolving 32 religious temperament of Ashley. 1.3 Conclusion: A son of the Clapham Sect or a brother of the Recordites? 64 Part II: A just estimate of rank and property: Locating Ashley’s place within the 67 tradition of paternalism 2.1 Identifying the character of Ashley’s paternalism 68 2.2 How Tory paternalist ideas influenced the emerging consciousness of Ashley in the 88 pre-Victorian era 2.3 The place of Ashley’s paternalism within the British Tory and Whig traditions 132 2.4 Conclusion: Paternalism in the ‘name of the people’ 144 Part III: Something admirably patrician in his estimation of Christianity: Ashley 147 and the emerging synthesis between Evangelicalism and Tory paternalism 3.1 Common ground forged between Tory paternalism and early Victorian Evangelicalism 148 3.2 Ashley and the factory reform movement: Project of Tory paternalism or 203 by-product of Evangelical social concern? 3.3 The coalescence of these two belief systems in the emerging political philosophy of 230 Ashley 3.4 Conclusion: Making Evangelicalism a patrician creed 237 Part IV: Ashley and the milieux of Victorian Evangelicalism 240 4.1 Locating Ashley’s place within the Victorian Evangelical Terrain 242 4.2 Thy kingdom come, thy will be done: The premillennial eschatology and 255 Evangelical activism of Ashley 4.3 Desire for the nations: Ashley and Victorian Evangelical attitudes to imperialism, 264 race and the ‘Jewish question’. -

UF Survives Outburst from Nation's Leading

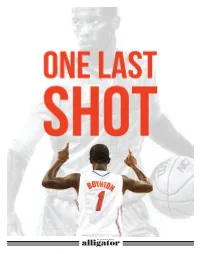

Road to the Final Four Sports Editor Joe Morgan � Cover illustration photos Aundre Larrow � Cover design Aundre Larrow and Landon Watnick Alligator, Friday, March 22, 2013 Building His Legacy Javier Edwards / Alligator Senior guard Kenny Boynton (1) smiles after cutting the final strands of the net after Florida’s 66-40 win against Vanderbilt on March 6 in the O’Connell Center. Boynton has won to SEC championships as a Gator. Kenny on the hardwood. Together, they helped Ely win the FHSAA Class 6A state Final Four chase, academics motivated Boynton to stay at Florida championship in 2006. But after his sophomore season, Kenny LANDON WATNICK Despite a few shooting slumps along Boynton is truly loved inside of our team made a surprising decision, transferring Alligator Writer the way, Boynton has averaged 14.1 points because he’s a great teammate. When he’s from Ely to American Heritage. per game on 39.9 percent shooting in 141 making some shots, it livens up our team, Academics were as one of the main rea- Many people thought Kenny Boynton games. because our team looks to him in a lot of Boynton never imagined he would re- sons Kenny transferred. would leave Florida after his freshman sea- During his time in Gainesville, Boynton ways.” main at Florida for four years, but his par- “I felt like Ely wasn’t a challenge for son three years ago. has helped the Gators earn two Elite Eight During his career, Boynton has devel- ents did. him,” Dana said. When he first committed to Florida on appearances and a pair of SEC regular-sea- oped multiple facets of his game outside of His family never wanted him to be a one- “I wanted him to be challenged and col- Oct. -

20 Years of Innovative Admissions After the Last Curtain Call

THE OWL THE ALUMNI MAGAZINE OF COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY SCHOOL OF GENERAL STUDIES After the Last Curtain Call: Dancers In Transition Forecasting Success: Remembering 20 Years of Innovative Dean Emeritus Admissions Peter J. Awn 2019-2020 TABLE OF CONTENTS THE OWL LETTER FROM THE DEAN THE ALUMNI MAGAZINE OF COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY SCHOOL OF GENERAL STUDIES Lisa Rosen-Metsch ’90 Dean Curtis Rodgers Vice Dean Jill Galas Hickey Associate Dean for Development and Alumni Relations Aviva Zablocki Director of Alumni Relations 18 14 12 Editor Dear GS Alumni and Friends, Allison Scola IN THIS ISSUE Communications, Special Projects As I reflect upon the heartbreak and challenges we have faced her network in the fashion industry to produce and donate PPE to frontline medical workers, to name just two of our alumni who Feature Story 14 The Transitional Dance since the last printing of The Owl, I am struck by my feelings of Since childhood, most professional dancers sacrificed, showed Contributors pride in how our amazing and resilient GS community has risen have made significant contributions. discipline, and gave themselves over dreams that required laser to meet these moments. When I step back, our school motto, Adrienne Anifant Lux Meanwhile, the accomplishments of members of our community focus on their goals. But what happens when their dream careers —the light shines in the darkness—is taking on Eileen Barroso in Tenebris Lucet extend across industries and causes. Poet Louise Glück, who are closer to the end than the beginning? new meaning. From the tragic loss of our beloved Dean Emeritus Nancy J. Brandwein attended GS in the 1960s, recently was awarded the Nobel Prize Peter J. -

Henry Ossawa Tanner: Modern Spirit Exhibition, Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts, Philadelphia

Review essay HenRy Ossawa TanneR: MOdeRn spiRiT exHibiTiOn, pennsylvania acadeMy Of fine aRTs, pHiladelpHia Alexia I. Hudson he Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts (PAFA) is located in Philadelphia within walking distance of City Hall. Founded in T1805 by painter and scientist Charles Willson Peale, sculptor William Rush, and other artists and business leaders, PAFA holds the distinction of being the oldest art school and art museum in the United States. Its current “historic landmark” build- ing opened in 1876, three years before Henry Ossawa Tanner (1859–1937) enrolled as one of PAFA’s first African American students. Tanner would later become the first African American artist to achieve international acclaim for his work. Today, PAFA is comprised of two adjacent buildings—the “historic landmark” building at 118 North Broad Street and the Samuel M. V. Hamilton Building at 128 N. Broad Street. The oldest building was designed by architects Frank Furness and George W. Hewitt and has been designated a National Historic Landmark, hence its name. In 1976 PAFA underwent a delicately managed restoration process to ensure that the archi- tectural and historical integrity of the building was maintained. pennsylvania history: a journal of mid-atlantic studies, vol. 79, no. 2, 2012. Copyright © 2012 The Pennsylvania Historical Association This content downloaded from 128.118.152.206 on Wed, 14 Mar 2018 15:39:34 UTC All use subject to http://about.jstor.org/terms PAH 79.2_06_Hudson.indd 238 18/04/12 12:28 AM review essays The Lenfest Plaza opened adjacent to PAFA on October 1, 2011, and was celebrated with the inaugural lighting of “Paint Torch,” a sculpture by inter- nationally renowned American artist Claes Oldenburg. -

'Nothing to Hide on Pow-Er Plant'

UNIVERSITY OF. HAWAII Lll:H~N\~ arianas %riet.r;,:~ Micronesia's Leading Newspaper Since 1972 ~ f:VVS US expert coming to help Villagomez insists: track PCB-related diseases By Jojo Dass 'Nothing to hide Variety News Staff RESIDENT Representative Juan N. Babauta has asked the U.S. Department of the Interior to defray the travel expenses of on pow-er plant' a medical expert who will be coming over to help doctors in screening islanders for possible By Haidee V. Eugenio the CNMI to rrieet our needs and exposure to cancer-causing Variety News Staff to encourage investment. But we polychlorinated biphenyl COMMONWEALTH Utilities must not make the mistake of (PCB). Corporation (CUC) Executive going into more debt than we need, Babauta had earlier sought Director Timothy P. Villagomez because that will lead to higher assistance to address concerns Juan N. Babauta yesterday faced the media to re utility rates and or an additional about PCB contamination in fute allegations CUC is deliber burden on the government," Tanapag from the Agency for those with PCB-related illnesses. ately attempting to delay the Villagomez told reporters. Toxic Substance and Disease Babauta explained that PCB awarding of contract for the con The procurement of the project, Registry, which in turn identi contamination levels among troversial $120 million power which remains to be the most ex fied a specialist that can estab Tanapag villagers has never been plant project. pensive one ever proposed in the He also sought to allay concerns lish human contamination. assessed despite lOyears of gov "'ti CNMI, has been going on for three Problem though is that ernment awareness of the prob about project, saying he will wel years now. -

Archives and Special Collections

Archives and Special Collections Dickinson College Carlisle, PA COLLECTION REGISTER Name: Price, Eli Kirk (1797-1884) MC 1999.13 Material: Family Papers (1797-1937) Volume: 0.75 linear feet (Document Boxes 1-2) Donation: Gift of Samuel and Anna D. Moyerman, 1965 Usage: These materials have been donated without restrictions on usage. BIOGRAPHICAL NOTE Eli Kirk Price was born near Brandywine in Chester County, Pennsylvania on July 20, 1797. He was the eighth of eleven children born to Rachel and Philip Price, members of the Society of Friends. Young Eli was raised within the Society and received his education at Westtown Boarding School in West Chester, Pennsylvania. After his years at Westtown, Price obtained his first business instruction in the store of John W. Townsend of West Chester. In 1815 Price went on to the countinghouse of Thomas P. Cope of Philadelphia, a shipping merchant in the Liverpool trade. While in the employ of Cope, Price familiarized himself with mercantile law and became interested in real estate law. In 1819 he began his legal studies under the tutelage of the prominent lawyer, John Sergeant of Philadelphia, and he was admitted to the Philadelphia Bar on May 28, 1822. On June 10, 1828 Price married Anna Embree, the daughter of James and Rebecca Embree. Together Eli and Anna had three children: Rebecca E. (Mrs. Hanson Whithers), John Sergeant, and Sibyl E (Mrs. Starr Nicholls). Anna Price died on June 4, 1862, a year and a half after their daughter Rebecca had died in January 1861. Price’s reputation as one of Philadelphia’s leading real estate attorneys led to his involvement in politics. -

Read John Berlinski's American Lawyer Trailblazer Profile

2021 THE AMERICAN LAWYER WEST WINNER’S NAME HERE | COMPANY NAME John Berlinski Kasowitz Benson Torres What was the genesis of the path that has made you a trailblazer? After successfully defending numerous profit participation disputes as Senior Vice President, Head of West Coast Television Litigation for NBCUniversal, I was approached by representatives of the talent who brought those claims and asked to “switch sides” and represent their clients against other major Holly- wood studios. Shortly thereafter, I left to launch Kasowitz’s entertainment practice with the goal of leveling the playing field against the bigger and better financed studios. What sort of change has resulted from the concept? : We have succeeded in shining the light on the historically opaque practice of “Hollywood Accounting,” resulting in more favorable outcomes for our clients obtained through arbitration, litigation, and informal settlements. While most of these matters are confidential, it is public knowledge that we secured a landmark $179 million arbitration award—the largest ever issued in a profit participation dispute—for actors Emily Deschanel and David Boreanaz, and producer Kathleen Reichs in connection with their profit participation interests in the television series “Bones”. Studios have responded to that and our other successes by starting to replace profit participation deals with less valuable series bonuses in which talent earns a bonus when a series meets benchmarks such as completing a certain number of seasons. What bearing will this have on the future?: Recently, the “streaming wars” involving Netflix, Disney+, HBOMax, and others have created significant demand for premium content, including content involving legacy profit participants. -

Chrome Girl Press

TM 8 FREE FORMULA, CRUELTY FREE, MADE IN USA ABOUT MELISSA & JAIME You could say that they have “nailed” it. You’d be right. It was one sunny girls’ afternoon while painting their daughters nails in which they realized that the Longtime friends Jaime Boreanaz and Melissa Ravo first product they were so carefully applying on their realized their uncanny similarities years ago upon meeting in children’s nails would soon end up making its way into the their neighborhood, situated in the exclusive hills above Los little girls’ mouths – whether while eating, chewing on their Angeles. Both mothers – whose young daughters inciden- nails, or licking off cupcake frosting. A quick scan of the tally became fast friends as well – found that their interests ingredients of the polishes became a nauseating realiza- aligned perfectly. Both loved to travel the world, both were tion for the mothers. passionate about philanthropy, both indulged their daughters with fabulous and imaginative princess play-times that they In that moment, the idea behind Chrome Girl was born. would engage in together. A collaboration between Jaime and Melissa Chrome Girl was launched in February 2013 as a fashionable alterna- tive to the harsh and dangerous nail polishes currently on the market. It is a product that is 5-free, which means it is produced without formaldehyde, dibutyl phthalate (DBP), and toluene—plus formaldehyde resin and camphor, too. It is safe for even youngsters – but is on-trend, and ultra-cool. The debut collection boasts the hottest of colors – such as When In Chrome, Barely Legal, No Tan Lines, Shmexy and Pillow Talk, to name a few - and is intended for women of all ages, backgrounds and ethnicities. -

Reminder List of Productions Eligible for the 86Th Academy Awards

REMINDER LIST OF PRODUCTIONS ELIGIBLE FOR THE 86TH ACADEMY AWARDS ABOUT TIME Notes Domhnall Gleeson. Rachel McAdams. Bill Nighy. Tom Hollander. Lindsay Duncan. Margot Robbie. Lydia Wilson. Richard Cordery. Joshua McGuire. Tom Hughes. Vanessa Kirby. Will Merrick. Lisa Eichhorn. Clemmie Dugdale. Harry Hadden-Paton. Mitchell Mullen. Jenny Rainsford. Natasha Powell. Mark Healy. Ben Benson. Philip Voss. Tom Godwin. Pal Aron. Catherine Steadman. Andrew Martin Yates. Charlie Barnes. Verity Fullerton. Veronica Owings. Olivia Konten. Sarah Heller. Jaiden Dervish. Jacob Francis. Jago Freud. Ollie Phillips. Sophie Pond. Sophie Brown. Molly Seymour. Matilda Sturridge. Tom Stourton. Rebecca Chew. Jon West. Graham Richard Howgego. Kerrie Liane Studholme. Ken Hazeldine. Barbar Gough. Jon Boden. Charlie Curtis. ADMISSION Tina Fey. Paul Rudd. Michael Sheen. Wallace Shawn. Nat Wolff. Lily Tomlin. Gloria Reuben. Olek Krupa. Sonya Walger. Christopher Evan Welch. Travaris Meeks-Spears. Ann Harada. Ben Levin. Daniel Joseph Levy. Maggie Keenan-Bolger. Elaine Kussack. Michael Genadry. Juliet Brett. John Brodsky. Camille Branton. Sarita Choudhury. Ken Barnett. Travis Bratten. Tanisha Long. Nadia Alexander. Karen Pham. Rob Campbell. Roby Sobieski. Lauren Anne Schaffel. Brian Charles Johnson. Lipica Shah. Jarod Einsohn. Caliaf St. Aubyn. Zita-Ann Geoffroy. Laura Jordan. Sarah Quinn. Jason Blaj. Zachary Unger. Lisa Emery. Mihran Shlougian. Lynne Taylor. Brian d'Arcy James. Leigha Handcock. David Simins. Brad Wilson. Ryan McCarty. Krishna Choudhary. Ricky Jones. Thomas Merckens. Alan Robert Southworth. ADORE Naomi Watts. Robin Wright. Xavier Samuel. James Frecheville. Sophie Lowe. Jessica Tovey. Ben Mendelsohn. Gary Sweet. Alyson Standen. Skye Sutherland. Sarah Henderson. Isaac Cocking. Brody Mathers. Alice Roberts. Charlee Thomas. Drew Fairley. Rowan Witt. Sally Cahill. -

Inventory and Analysis of Archaeological Site Occurrence on the Atlantic Outer Continental Shelf

OCS Study BOEM 2012-008 Inventory and Analysis of Archaeological Site Occurrence on the Atlantic Outer Continental Shelf U.S. Department of the Interior Bureau of Ocean Energy Management Gulf of Mexico OCS Region OCS Study BOEM 2012-008 Inventory and Analysis of Archaeological Site Occurrence on the Atlantic Outer Continental Shelf Author TRC Environmental Corporation Prepared under BOEM Contract M08PD00024 by TRC Environmental Corporation 4155 Shackleford Road Suite 225 Norcross, Georgia 30093 Published by U.S. Department of the Interior Bureau of Ocean Energy Management New Orleans Gulf of Mexico OCS Region May 2012 DISCLAIMER This report was prepared under contract between the Bureau of Ocean Energy Management (BOEM) and TRC Environmental Corporation. This report has been technically reviewed by BOEM, and it has been approved for publication. Approval does not signify that the contents necessarily reflect the views and policies of BOEM, nor does mention of trade names or commercial products constitute endoresements or recommendation for use. It is, however, exempt from review and compliance with BOEM editorial standards. REPORT AVAILABILITY This report is available only in compact disc format from the Bureau of Ocean Energy Management, Gulf of Mexico OCS Region, at a charge of $15.00, by referencing OCS Study BOEM 2012-008. The report may be downloaded from the BOEM website through the Environmental Studies Program Information System (ESPIS). You will be able to obtain this report also from the National Technical Information Service in the near future. Here are the addresses. You may also inspect copies at selected Federal Depository Libraries. U.S. Department of the Interior U.S. -

Lublin Studies in Modern Languages and Literature

Lublin Studies in Modern Languages and Literature VOL. 43 No 2 (2019) ii e-ISSN: 2450-4580 Publisher: Maria Curie-Skłodowska University Lublin, Poland Maria Curie-Skłodowska University Press MCSU Library building, 3rd floor ul. Idziego Radziszewskiego 11, 20-031 Lublin, Poland phone: (081) 537 53 04 e-mail: [email protected] www.wydawnictwo.umcs.lublin.pl Editorial Board Editor-in-Chief Jolanta Knieja, Maria Curie-Skłodowska University, Lublin, Poland Deputy Editors-in-Chief Jarosław Krajka, Maria Curie-Skłodowska University, Lublin, Poland Anna Maziarczyk, Maria Curie-Skłodowska University, Lublin, Poland Statistical Editor Tomasz Krajka, Lublin University of Technology, Poland International Advisory Board Anikó Ádám, Pázmány Péter Catholic University, Hungary Monika Adamczyk-Garbowska, Maria Curie-Sklodowska University, Poland Ruba Fahmi Bataineh, Yarmouk University, Jordan Alejandro Curado, University of Extramadura, Spain Saadiyah Darus, National University of Malaysia, Malaysia Janusz Golec, Maria Curie-Sklodowska University, Poland Margot Heinemann, Leipzig University, Germany Christophe Ippolito, Georgia Institute of Technology, United States of America Vita Kalnberzina, University of Riga, Latvia Henryk Kardela, Maria Curie-Sklodowska University, Poland Ferit Kilickaya, Mehmet Akif Ersoy University, Turkey Laure Lévêque, University of Toulon, France Heinz-Helmut Lüger, University of Koblenz-Landau, Germany Peter Schnyder, University of Upper Alsace, France Alain Vuillemin, Artois University, France v Indexing Peer Review Process 1. Each article is reviewed by two independent reviewers not affiliated to the place of work of the author of the article or the publisher. 2. For publications in foreign languages, at least one reviewer’s affiliation should be in a different country than the country of the author of the article. -

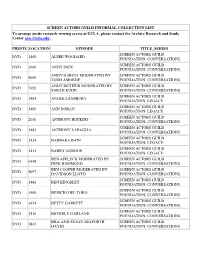

SCREEN ACTORS GUILD INFORMAL COLLECTION LIST to Arrange Onsite Research Viewing Access at UCLA, Please Contact the Archive Research and Study Center [email protected]

SCREEN ACTORS GUILD INFORMAL COLLECTION LIST To arrange onsite research viewing access at UCLA, please contact the Archive Research and Study Center [email protected] . PREFIX LOCATION EPISODE TITLE_SERIES SCREEN ACTORS GUILD DVD 1460 ALFRE WOODARD FOUNDATION: CONVERSATIONS SCREEN ACTORS GUILD DVD 1669 ANDY DICK FOUNDATION: CONVERSATIONS ANDY GARCIA MODERATED BY SCREEN ACTORS GUILD DVD 8699 TODD AMORDE FOUNDATION: CONVERSATIONS ANDY RICHTER MODERATED BY SCREEN ACTORS GUILD DVD 7020 SARAH KUHN FOUNDATION: CONVERSATIONS SCREEN ACTORS GUILD DVD 1484 ANGLE LANSBURY FOUNDATION: LEGACY SCREEN ACTORS GUILD DVD 1409 ANN DORAN FOUNDATION: LEGACY SCREEN ACTORS GUILD DVD 2010 ANTHONY HOPKINS FOUNDATION: CONVERSATIONS SCREEN ACTORS GUILD DVD 1483 ANTHONY LAPAGLIA FOUNDATION: CONVERSATIONS SCREEN ACTORS GUILD DVD 1434 BARBARA BAIN FOUNDATION: LEGACY SCREEN ACTORS GUILD DVD 1413 BARRY GORDON FOUNDATION: LEGACY BEN AFFLECK MODERATED BY SCREEN ACTORS GUILD DVD 6348 PETE HAMMOND FOUNDATION: CONVERSATIONS BEN COOPER MODERATED BY SCREEN ACTORS GUILD DVD 8697 DAVIDSON LLOYD FOUNDATION: CONVERSATIONS SCREEN ACTORS GUILD DVD 1486 BEN KINGSLEY FOUNDATION: CONVERSATIONS SCREEN ACTORS GUILD DVD 1500 BENICIO DEL TORO FOUNDATION: CONVERSATIONS SCREEN ACTORS GUILD DVD 1674 BETTY GARRETT FOUNDATION: CONVERSATIONS SCREEN ACTORS GUILD DVD 1416 BEVERLY GARLAND FOUNDATION: CONVERSATIONS BILL AND SUSAN SEAFORTH SCREEN ACTORS GUILD DVD 1843 HAYES FOUNDATION: CONVERSATIONS BILL PAXTON MODERATED BY SCREEN ACTORS GUILD DVD 7019 JENELLE RILEY FOUNDATION: CONVERSATIONS SCREEN ACTORS