Genetic Variant of TTLL11 Gene and Subsequent Ciliary Defects Are Associated with Idiopathic Scoliosis in a 5-Generation UK Fami

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Autism Multiplex Family with 16P11.2P12.2 Microduplication Syndrome in Monozygotic Twins and Distal 16P11.2 Deletion in Their Brother

European Journal of Human Genetics (2012) 20, 540–546 & 2012 Macmillan Publishers Limited All rights reserved 1018-4813/12 www.nature.com/ejhg ARTICLE Autism multiplex family with 16p11.2p12.2 microduplication syndrome in monozygotic twins and distal 16p11.2 deletion in their brother Anne-Claude Tabet1,2,3,4, Marion Pilorge2,3,4, Richard Delorme5,6,Fre´de´rique Amsellem5,6, Jean-Marc Pinard7, Marion Leboyer6,8,9, Alain Verloes10, Brigitte Benzacken1,11,12 and Catalina Betancur*,2,3,4 The pericentromeric region of chromosome 16p is rich in segmental duplications that predispose to rearrangements through non-allelic homologous recombination. Several recurrent copy number variations have been described recently in chromosome 16p. 16p11.2 rearrangements (29.5–30.1 Mb) are associated with autism, intellectual disability (ID) and other neurodevelopmental disorders. Another recognizable but less common microdeletion syndrome in 16p11.2p12.2 (21.4 to 28.5–30.1 Mb) has been described in six individuals with ID, whereas apparently reciprocal duplications, studied by standard cytogenetic and fluorescence in situ hybridization techniques, have been reported in three patients with autism spectrum disorders. Here, we report a multiplex family with three boys affected with autism, including two monozygotic twins carrying a de novo 16p11.2p12.2 duplication of 8.95 Mb (21.28–30.23 Mb) characterized by single-nucleotide polymorphism array, encompassing both the 16p11.2 and 16p11.2p12.2 regions. The twins exhibited autism, severe ID, and dysmorphic features, including a triangular face, deep-set eyes, large and prominent nasal bridge, and tall, slender build. The eldest brother presented with autism, mild ID, early-onset obesity and normal craniofacial features, and carried a smaller, overlapping 16p11.2 microdeletion of 847 kb (28.40–29.25 Mb), inherited from his apparently healthy father. -

Dual Proteome-Scale Networks Reveal Cell-Specific Remodeling of the Human Interactome

bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.01.19.905109; this version posted January 19, 2020. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder. All rights reserved. No reuse allowed without permission. Dual Proteome-scale Networks Reveal Cell-specific Remodeling of the Human Interactome Edward L. Huttlin1*, Raphael J. Bruckner1,3, Jose Navarrete-Perea1, Joe R. Cannon1,4, Kurt Baltier1,5, Fana Gebreab1, Melanie P. Gygi1, Alexandra Thornock1, Gabriela Zarraga1,6, Stanley Tam1,7, John Szpyt1, Alexandra Panov1, Hannah Parzen1,8, Sipei Fu1, Arvene Golbazi1, Eila Maenpaa1, Keegan Stricker1, Sanjukta Guha Thakurta1, Ramin Rad1, Joshua Pan2, David P. Nusinow1, Joao A. Paulo1, Devin K. Schweppe1, Laura Pontano Vaites1, J. Wade Harper1*, Steven P. Gygi1*# 1Department of Cell Biology, Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA, 02115, USA. 2Broad Institute, Cambridge, MA, 02142, USA. 3Present address: ICCB-Longwood Screening Facility, Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA, 02115, USA. 4Present address: Merck, West Point, PA, 19486, USA. 5Present address: IQ Proteomics, Cambridge, MA, 02139, USA. 6Present address: Vor Biopharma, Cambridge, MA, 02142, USA. 7Present address: Rubius Therapeutics, Cambridge, MA, 02139, USA. 8Present address: RPS North America, South Kingstown, RI, 02879, USA. *Correspondence: [email protected] (E.L.H.), [email protected] (J.W.H.), [email protected] (S.P.G.) #Lead Contact: [email protected] bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.01.19.905109; this version posted January 19, 2020. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder. -

Advancing a Clinically Relevant Perspective of the Clonal Nature of Cancer

Advancing a clinically relevant perspective of the clonal nature of cancer Christian Ruiza,b, Elizabeth Lenkiewicza, Lisa Eversa, Tara Holleya, Alex Robesona, Jeffrey Kieferc, Michael J. Demeurea,d, Michael A. Hollingsworthe, Michael Shenf, Donna Prunkardf, Peter S. Rabinovitchf, Tobias Zellwegerg, Spyro Moussesc, Jeffrey M. Trenta,h, John D. Carpteni, Lukas Bubendorfb, Daniel Von Hoffa,d, and Michael T. Barretta,1 aClinical Translational Research Division, Translational Genomics Research Institute, Scottsdale, AZ 85259; bInstitute for Pathology, University Hospital Basel, University of Basel, 4031 Basel, Switzerland; cGenetic Basis of Human Disease, Translational Genomics Research Institute, Phoenix, AZ 85004; dVirginia G. Piper Cancer Center, Scottsdale Healthcare, Scottsdale, AZ 85258; eEppley Institute for Research in Cancer and Allied Diseases, Nebraska Medical Center, Omaha, NE 68198; fDepartment of Pathology, University of Washington, Seattle, WA 98105; gDivision of Urology, St. Claraspital and University of Basel, 4058 Basel, Switzerland; hVan Andel Research Institute, Grand Rapids, MI 49503; and iIntegrated Cancer Genomics Division, Translational Genomics Research Institute, Phoenix, AZ 85004 Edited* by George F. Vande Woude, Van Andel Research Institute, Grand Rapids, MI, and approved June 10, 2011 (received for review March 11, 2011) Cancers frequently arise as a result of an acquired genomic insta- on the basis of morphology alone (8). Thus, the application of bility and the subsequent clonal evolution of neoplastic cells with purification methods such as laser capture microdissection does variable patterns of genetic aberrations. Thus, the presence and not resolve the complexities of many samples. A second approach behaviors of distinct clonal populations in each patient’s tumor is to passage tumor biopsies in tissue culture or in xenografts (4, 9– may underlie multiple clinical phenotypes in cancers. -

Product Description SALSA® MLPA® Probemix P463-A2 MRKH to Be Used with the MLPA General Protocol

MRC-Holland ® Product Description version A2-01; Issued 16 July 2020 MLPA Product Description SALSA® MLPA® Probemix P463-A2 MRKH To be used with the MLPA General Protocol. Version A2. As compared to version A1, five reference probes have been replaced and one probe length has been adjusted. For complete product history see page 7. Catalogue numbers: P463-025R: SALSA MLPA Probemix P463 MRKH, 25 reactions. P463-050R: SALSA MLPA Probemix P463 MRKH, 50 reactions. P463-100R: SALSA MLPA Probemix P463 MRKH, 100 reactions. To be used in combination with a SALSA MLPA reagent kit and Coffalyser.Net data analysis software. MLPA reagent kits are either provided with FAM or Cy5.0 dye-labelled PCR primer, suitable for Applied Biosystems and Beckman/SCIEX capillary sequencers, respectively (see www.mlpa.com). Certificate of Analysis: Information regarding storage conditions, quality tests, and a sample electropherogram from the current sales lot is available at www.mlpa.com. Precautions and warnings: For professional use only. Always consult the most recent product description AND the MLPA General Protocol before use: www.mlpa.com. It is the responsibility of the user to be aware of the latest scientific knowledge of the application before drawing any conclusions from findings generated with this product. General information: The SALSA MLPA Probemix P463 MRKH is a research use only (RUO) assay for the detection of deletions or duplications in the TBX6, LHX1, HNF1B, and TBX1 genes, which are associated with Mayer-Rokitansky-Küster-Hauser syndrome (MRKH). MRKH is characterised by normal physical development of the secondary sexual characteristics and a normal female 46,XX karyotype but with complete aplasia of the uterus, cervix, and superior parts of vagina leading to failure to menstruate and infertility. -

A Framework to Identify Contributing Genes in Patients with Phelan

A framework to identify contributing genes in patients with Phelan-McDermid syndrome Anne-Claude Tabet, Thomas Rolland, Marie Ducloy, Jonathan Levy, Julien Buratti, Alexandre Mathieu, Damien Haye, Laurence Perrin, Céline Dupont, Sandrine Passemard, et al. To cite this version: Anne-Claude Tabet, Thomas Rolland, Marie Ducloy, Jonathan Levy, Julien Buratti, et al.. A frame- work to identify contributing genes in patients with Phelan-McDermid syndrome. Genomic Medicine, Springer Verlag, 2017, 2, pp.32. 10.1038/s41525-017-0035-2. hal-01738521 HAL Id: hal-01738521 https://hal.umontpellier.fr/hal-01738521 Submitted on 20 Mar 2018 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Distributed under a Creative Commons Attribution| 4.0 International License www.nature.com/npjgenmed ARTICLE OPEN A framework to identify contributing genes in patients with Phelan-McDermid syndrome Anne-Claude Tabet 1,2,3,4, Thomas Rolland2,3,4, Marie Ducloy2,3,4, Jonathan Lévy1, Julien Buratti2,3,4, Alexandre Mathieu2,3,4, Damien Haye1, Laurence Perrin1, Céline Dupont 1, Sandrine -

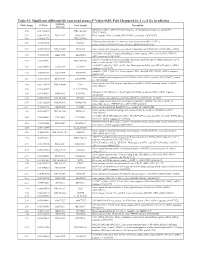

(P -Value<0.05, Fold Change≥1.4), 4 Vs. 0 Gy Irradiation

Table S1: Significant differentially expressed genes (P -Value<0.05, Fold Change≥1.4), 4 vs. 0 Gy irradiation Genbank Fold Change P -Value Gene Symbol Description Accession Q9F8M7_CARHY (Q9F8M7) DTDP-glucose 4,6-dehydratase (Fragment), partial (9%) 6.70 0.017399678 THC2699065 [THC2719287] 5.53 0.003379195 BC013657 BC013657 Homo sapiens cDNA clone IMAGE:4152983, partial cds. [BC013657] 5.10 0.024641735 THC2750781 Ciliary dynein heavy chain 5 (Axonemal beta dynein heavy chain 5) (HL1). 4.07 0.04353262 DNAH5 [Source:Uniprot/SWISSPROT;Acc:Q8TE73] [ENST00000382416] 3.81 0.002855909 NM_145263 SPATA18 Homo sapiens spermatogenesis associated 18 homolog (rat) (SPATA18), mRNA [NM_145263] AA418814 zw01a02.s1 Soares_NhHMPu_S1 Homo sapiens cDNA clone IMAGE:767978 3', 3.69 0.03203913 AA418814 AA418814 mRNA sequence [AA418814] AL356953 leucine-rich repeat-containing G protein-coupled receptor 6 {Homo sapiens} (exp=0; 3.63 0.0277936 THC2705989 wgp=1; cg=0), partial (4%) [THC2752981] AA484677 ne64a07.s1 NCI_CGAP_Alv1 Homo sapiens cDNA clone IMAGE:909012, mRNA 3.63 0.027098073 AA484677 AA484677 sequence [AA484677] oe06h09.s1 NCI_CGAP_Ov2 Homo sapiens cDNA clone IMAGE:1385153, mRNA sequence 3.48 0.04468495 AA837799 AA837799 [AA837799] Homo sapiens hypothetical protein LOC340109, mRNA (cDNA clone IMAGE:5578073), partial 3.27 0.031178378 BC039509 LOC643401 cds. [BC039509] Homo sapiens Fas (TNF receptor superfamily, member 6) (FAS), transcript variant 1, mRNA 3.24 0.022156298 NM_000043 FAS [NM_000043] 3.20 0.021043295 A_32_P125056 BF803942 CM2-CI0135-021100-477-g08 CI0135 Homo sapiens cDNA, mRNA sequence 3.04 0.043389246 BF803942 BF803942 [BF803942] 3.03 0.002430239 NM_015920 RPS27L Homo sapiens ribosomal protein S27-like (RPS27L), mRNA [NM_015920] Homo sapiens tumor necrosis factor receptor superfamily, member 10c, decoy without an 2.98 0.021202829 NM_003841 TNFRSF10C intracellular domain (TNFRSF10C), mRNA [NM_003841] 2.97 0.03243901 AB002384 C6orf32 Homo sapiens mRNA for KIAA0386 gene, partial cds. -

Novel ENU-Induced Mutation in Tbx6 Causes Dominant Spondylocostal Dysostosis-Like Vertebral Malformations in the Rat

RESEARCH ARTICLE Novel ENU-Induced Mutation in Tbx6 Causes Dominant Spondylocostal Dysostosis-Like Vertebral Malformations in the Rat Koichiro Abe1*, Nobuhiko Takamatsu2, Kumiko Ishikawa1, Toshiko Tsurumi3, Sho Tanimoto1, Yukina Sakurai2, Thomas Lisse4, Kenji Imai1, Tadao Serikawa3, Tomoji Mashimo3¤ 1 Department of Molecular Life Science, Tokai University School of Medicine, Isehara, Kanagawa, Japan, 2 Department of Biosciences, School of Science, Kitasato University, Sagamihara, Kanagawa, Japan, 3 Institute of Laboratory Animals, Graduate School of Medicine, Kyoto University, Kyoto, Japan, 4 MDI Biological Laboratory, Davis Center for Regenerative Biology and Medicine, Bar Harbor, Maine, United States of America ¤ Current address: Institute of Experimental Animal Sciences, Graduate School of Medicine, Osaka University, Osaka, Japan. * [email protected] OPEN ACCESS Abstract Citation: Abe K, Takamatsu N, Ishikawa K, Tsurumi T, Tanimoto S, Sakurai Y, et al. (2015) Novel ENU- Congenital vertebral malformations caused by embryonic segmentation defects are rela- Induced Mutation in Tbx6 Causes Dominant tively common in humans and domestic animals. Although reverse genetics approaches in Spondylocostal Dysostosis-Like Vertebral mice have provided information on the molecular mechanisms of embryonic somite seg- Malformations in the Rat. PLoS ONE 10(6): e0130231. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0130231 mentation, hypothesis-driven approaches cannot adequately reflect human dysmorphology within the population. In a N-ethyl-N-nitrosourea (ENU) mutagenesis project in Kyoto, the Editor: Tom J. Carney, Institute of Molecular and Cell Oune Biology, SINGAPORE mutant rat strain was isolated due to a short and kinked caudal vertebra phenotype. Skeletal staining of heterozygous rats showed partial loss of the cervical vertebrae as well Received: July 27, 2014 as hemivertebrae and fused vertebral blocks in lumbar and sacral vertebrae. -

Title Human Genetic Diversity Possibly Determines Human's Compliance to COVID-19

Preprints (www.preprints.org) | NOT PEER-REVIEWED | Posted: 16 April 2020 Title Human genetic diversity possibly determines human's compliance to COVID-19 1* 2 1 1 1 1 2 2 Yiqiang Zhao , Yongji Liu , Sa Li , Yuzhan Wang , Lina Bu , Qi Liu , Hongyi Lv , Fang Wan , Lida Wu2, Zeming Ning3, Yuchun Gu2,4* 1. Beijing Advanced Innovation Center for Food Nutrition and Human Health, China Agricultural University, Beijing, China 2. Allife Medicine Ltd., Beijing, China 3. The Wellcome Sanger Institute, Wellcome Genome Campus, Cambridge, UK 4. Regenerative Medicine Center, Aston University, Birmingham, UK Corresponding Author Prof. Yiqiang Zhao Beijing Advanced Innovation Center for Food Nutrition and Human Health China Agricultural University Beijing, China Email: [email protected] And Prof. Yuchun Gu The regenerative Medicine Center Aston University Birmingham, UK & Allife Medicine Co.Ltd Beijing, China Email: [email protected] © 2020 by the author(s). Distributed under a Creative Commons CC BY license. Preprints (www.preprints.org) | NOT PEER-REVIEWED | Posted: 16 April 2020 Abstract The rapid spread of the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) is a serious threat to public health systems globally and is subsequently, a cause of anxiety and panic within human society. Understanding the mechanisms and reducing the chances of having severe symptoms from COVID-19 will play an essential role in treating the disease, and become an urgent task to calm the panic. However, the COVID-19 test developed to identify virus carriers is unable to predict symptom development in individuals upon infection. Experiences from other plagues in human history and COVID-19 statistics suggest that genetic factors may determine the compliance with the virus, i.e., severe, mild, and asymptomatic. -

Egfr Activates a Taz-Driven Oncogenic Program in Glioblastoma

EGFR ACTIVATES A TAZ-DRIVEN ONCOGENIC PROGRAM IN GLIOBLASTOMA by Minling Gao A thesis submitted to Johns Hopkins University in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Baltimore, Maryland March 2020 ©2020 Minling Gao All rights reserved Abstract Hyperactivated EGFR signaling is associated with about 45% of Glioblastoma (GBM), the most aggressive and lethal primary brain tumor in humans. However, the oncogenic transcriptional events driven by EGFR are still incompletely understood. We studied the role of the transcription factor TAZ to better understand master transcriptional regulators in mediating the EGFR signaling pathway in GBM. The transcriptional coactivator with PDZ- binding motif (TAZ) and its paralog gene, the Yes-associated protein (YAP) are two transcriptional co-activators that play important roles in multiple cancer types and are regulated in a context-dependent manner by various upstream signaling pathways, e.g. the Hippo, WNT and GPCR signaling. In GBM cells, TAZ functions as an oncogene that drives mesenchymal transition and radioresistance. This thesis intends to broaden our understanding of EGFR signaling and TAZ regulation in GBM. In patient-derived GBM cell models, EGF induced TAZ and its known gene targets through EGFR and downstream tyrosine kinases (ERK1/2 and STAT3). In GBM cells with EGFRvIII, an EGF-independent and constitutively active mutation, TAZ showed EGF- independent hyperactivation when compared to EGFRvIII-negative cells. These results revealed a novel EGFR-TAZ signaling axis in GBM cells. The second contribution of this thesis is that we performed next-generation sequencing to establish the first genome-wide map of EGF-induced TAZ target genes. -

Analysis of Mouse Embryonic Patterning and Morphogenesis By

Analysis of mouse embryonic patterning and INAUGURAL ARTICLE morphogenesis by forward genetics Marı´a J. Garcı´a-Garcı´a*,Jonathan T. Eggenschwiler*†, Tamara Caspary*‡, Heather L. Alcorn*, Michael R. Wyler*, Danwei Huangfu*§, Andrew S. Rakeman*¶, Jeffrey D. Lee*, Evan H. Feinberg*ʈ, John R. Timmer*,**, and Kathryn V. Anderson*†† *Developmental Biology Program, Sloan–Kettering Institute, 1275 York Avenue, New York, NY 10021; §Neuroscience Program and ¶Molecular and Cell Biology Program, Weill Graduate School of Medical Sciences, Cornell University, 445 East 69th Street, New York, NY 10021; and ʈWeill Graduate School of Medical Sciences at Cornell University͞The Rockefeller University͞Sloan–Kettering Institute Tri-Institutional M.D.-Ph.D. Program, 1300 York Avenue, New York, NY 10021 This contribution is part of the special series of Inaugural Articles by members of the National Academy of Sciences elected on April 20, 2004. Contributed by Kathryn V. Anderson, February 8, 2005 Many aspects of the genetic control of mammalian embryogenesis proaches in other laboratories that focused on later stages of cannot be extrapolated from other animals. Taking a forward embryonic and fetal development in the mouse have also genetic approach, we have induced recessive mutations by treat- identified novel mutations successfully (9–11). With the avail- ment of mice with ethylnitrosourea and have identified 43 muta- ability of the mouse genome sequence, it has become straight- tions that affect early morphogenesis and patterning, including 38 forward to identify the genes responsible for the mutant genes that have not been studied previously. The molecular lesions phenotypes. responsible for 14 mutations were identified, including mutations Here, we describe the identification of 43 recessive mutations in nine genes that had not been characterized previously. -

Diagnostic Interpretation of Genetic Studies in Patients with Primary

AAAAI Work Group Report Diagnostic interpretation of genetic studies in patients with primary immunodeficiency diseases: A working group report of the Primary Immunodeficiency Diseases Committee of the American Academy of Allergy, Asthma & Immunology Ivan K. Chinn, MD,a,b Alice Y. Chan, MD, PhD,c Karin Chen, MD,d Janet Chou, MD,e,f Morna J. Dorsey, MD, MMSc,c Joud Hajjar, MD, MS,a,b Artemio M. Jongco III, MPH, MD, PhD,g,h,i Michael D. Keller, MD,j Lisa J. Kobrynski, MD, MPH,k Attila Kumanovics, MD,l Monica G. Lawrence, MD,m Jennifer W. Leiding, MD,n,o,p Patricia L. Lugar, MD,q Jordan S. Orange, MD, PhD,r,s Kiran Patel, MD,k Craig D. Platt, MD, PhD,e,f Jennifer M. Puck, MD,c Nikita Raje, MD,t,u Neil Romberg, MD,v,w Maria A. Slack, MD,x,y Kathleen E. Sullivan, MD, PhD,v,w Teresa K. Tarrant, MD,z Troy R. Torgerson, MD, PhD,aa,bb and Jolan E. Walter, MD, PhDn,o,cc Houston, Tex; San Francisco, Calif; Salt Lake City, Utah; Boston, Mass; Great Neck and Rochester, NY; Washington, DC; Atlanta, Ga; Rochester, Minn; Charlottesville, Va; St Petersburg, Fla; Durham, NC; Kansas City, Mo; Philadelphia, Pa; and Seattle, Wash AAAAI Position Statements,Work Group Reports, and Systematic Reviews are not to be considered to reflect current AAAAI standards or policy after five years from the date of publication. The statement below is not to be construed as dictating an exclusive course of action nor is it intended to replace the medical judgment of healthcare professionals. -

S41419-021-03972-6.Pdf

www.nature.com/cddis ARTICLE OPEN Primed to die: an investigation of the genetic mechanisms underlying noise-induced hearing loss and cochlear damage in homozygous Foxo3-knockout mice ✉ Holly J. Beaulac1,3, Felicia Gilels1,4, Jingyuan Zhang1,5, Sarah Jeoung2 and Patricia M. White 1 © The Author(s) 2021 The prevalence of noise-induced hearing loss (NIHL) continues to increase, with limited therapies available for individuals with cochlear damage. We have previously established that the transcription factor FOXO3 is necessary to preserve outer hair cells (OHCs) and hearing thresholds up to two weeks following mild noise exposure in mice. The mechanisms by which FOXO3 preserves cochlear cells and function are unknown. In this study, we analyzed the immediate effects of mild noise exposure on wild-type, Foxo3 heterozygous (Foxo3+/−), and Foxo3 knock-out (Foxo3−/−) mice to better understand FOXO3’s role(s) in the mammalian cochlea. We used confocal and multiphoton microscopy to examine well-characterized components of noise-induced damage including calcium regulators, oxidative stress, necrosis, and caspase-dependent and caspase-independent apoptosis. Lower immunoreactivity of the calcium buffer Oncomodulin in Foxo3−/− OHCs correlated with cell loss beginning 4 h post-noise exposure. Using immunohistochemistry, we identified parthanatos as the cell death pathway for OHCs. Oxidative stress response pathways were not significantly altered in FOXO3’s absence. We used RNA sequencing to identify and RT-qPCR to confirm differentially expressed genes. We further investigated a gene downregulated in the unexposed Foxo3−/− mice that may contribute to OHC noise susceptibility. Glycerophosphodiester phosphodiesterase domain containing 3 (GDPD3), a possible endogenous source of lysophosphatidic acid (LPA), has not previously been described in the cochlea.