Programming the USSR: Leonid V. Kantorovich in Context

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Original Version of This Chapter Was Revised: the Copyright Line Was Incorrect

The original version of this chapter was revised: The copyright line was incorrect. This has been corrected. The Erratum to this chapter is available at DOI: 10.1007/978-0-387-35615-0_52 D. Passey et al. (eds.), TelE-Learning © IFIP International Federation for Information Processing 2002 62 Yakov I. Fet. scientists from CEE countries, including two distinguished Russian scientists, Sergey Lebedev, who 'designed and constructed the first computer in the Soviet Union and founded the Soviet computer industry' , and Aleksey Lyapunov, who 'developed the first theory of operator methods for abstract programming and founded Soviet cybernetics and programming' (IEEE Computer, 1998; IEE Annals of the History of Computing, 1999). Of course, this reward recognised the important contribution of scientists and engineers from Central and Eastern Europe who played a significant role. However, in our opinion, it was just the first step in exploring and publishing this contradictory history which is of particular interest. It can serve a critical lesson to teachers and students who should learn the truth about suppressing an understanding of cybernetics and other advanced modem sciences behind the 'iron curtain'. What can be done today in order to make familiar to the world computer community the true history of computer science in CEE countries? Recently, a special group of Russian experts started their investigations in this field. The first result of their efforts was the book 'Essays on the History of computer science in Russia' (Pospelov and Fet, 1998) published in 1998 in Novosibirsk, Russia. In contrast to historical and biographical writings reflecting to a great extent the personal views of their authors, this book is built completely on the basis of authentic documents of the epoch. -

A Stakeholder Analysis of the Soviet Second Economy by CHOI, Jae

A Stakeholder Analysis of the Soviet Second Economy By CHOI, Jae-hyoung THESIS Submitted to KDI School of Public Policy and Management in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF PUBLIC POLICY 2015 A Stakeholder Analysis of the Soviet Second Economy By CHOI, Jae-hyoung THESIS Submitted to KDI School of Public Policy and Management in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF PUBLIC POLICY 2015 Professor Chang-Yong Choi A Stakeholder Analysis of the Soviet Second Economy By CHOI, Jae-hyoung THESIS Submitted to KDI School of Public Policy and Management in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF PUBLIC POLICY Committee in charge: Professor Chang Yong CHOI, Supervisor Professor Jung Ho YOO Professor June Soo LEE Approval as of April, 2015 Abstract This research aims to demonstrate, through a stakeholder analysis, that the institutionalization of the second economy in the Soviet Union was a natural byproduct of the interaction among three major stakeholders of Soviet society: the state, the bureaucracy, and the people. The three stakeholders responded to the incentive structure of the socialist economic system, interacting with each other in order to enhance their own interests. This research argues that their interaction was the internal necessity or dynamics that formed this informal market mechanism and elevated it to a characteristic feature of Soviet society. i Table of Contents Abstract ...................................................................................................................................... -

Journal of Economics and Management

Journal of Economics and Management ISSN 1732-1948 Vol. 39 (1) 2020 Sylwia Bąk https://orcid.org/0000-0003-4398-0865 Institute of Economics, Finance and Management Faculty of Management and Social Communication Jagiellonian University, Cracow, Poland [email protected] The problem of uncertainty and risk as a subject of research of the Nobel Prize Laureates in Economic Sciences Accepted by Editor Ewa Ziemba | Received: June 27, 2019 | Revised: October 29, 2019 | Accepted: November 8, 2019. Abstract Aim/purpose – The main aim of the present paper is to identify the problem of uncer- tainty and risk in research carried out by the Nobel Prize Laureates in Economic Sciences and its analysis by disciplines/sub-disciplines represented by the awarded researchers. Design/methodology/approach – The paper rests on the literature analysis, mostly analysis of research achievements of the Nobel Prize Laureates in Economic Sciences. Findings – Studies have determined that research on uncertainty and risk is carried out in many disciplines and sub-disciplines of economic sciences. In addition, it has been established that a number of researchers among the Nobel Prize laureates in the field of economic sciences, take into account the issues of uncertainty and risk. The analysis showed that researchers selected from the Nobel Prize laureates have made a significant contribution to raising awareness of the importance of uncertainty and risk in many areas of the functioning of individuals, enterprises and national economies. Research implications/limitations – Research analysis was based on a selected group of scientific research – Laureates of the Nobel Prize in Economic Sciences. However, thus confirmed ground-breaking and momentous nature of the research findings of this group of authors justifies the selective choice of the analysed research material. -

At Cold War's End: Complexity, Causes, and Counterfactuals

THE LONDON SCHOOL OF ECONOMICS AND POLITICAL SCIENCE At Cold War’s End: Complexity, Causes, and Counterfactuals Benjamin Mueller A thesis submitted to the Department of International Relations of the London School of Economics and Political Science for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. London, 1 October 2015 DECLARATION I certify that the thesis I present for examination for the MPhil/PhD degree of the London School of Economics and Political Science is solely my own work, except where I have clearly indicated that it is the work of others (in which case the extent of any work carried out by any other person is clearly identified in it). The copyright of this thesis rests with the author. Quotation from it is permitted, provided that full acknowledgement is made. This thesis may not be reproduced without my prior written consent. I warrant that this authorisation does not, to the best of my belief, infringe the rights of any third party. I declare that my thesis consists of 99,864 words. 2 ABSTRACT What caused the Cold War to end? In the following I examine the puzzle of the fast and peaceful conclusion of the bipolar superpower standoff, and point out the problems this creates for the study of International Relations (IR). I discuss prevailing explanations and point out their gaps, and offer the framework of complexity theory as a suitable complement to overcome the blind spots in IR’s reductionist methodologies. I argue that uncertainty and unpredictability are rooted in an international system that is best viewed as non-linear. -

The Importance of Osthandel: West German-Soviet Trade and the End of the Cold War, 1969-1991

The Importance of Osthandel: West German-Soviet Trade and the End of the Cold War, 1969-1991 Dissertation Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of the Ohio State University By Charles William Carter, M.A. Graduate Program in History The Ohio State University 2012 Dissertation Committee: Professor Carole Fink, Advisor Professor Mansel Blackford Professor Peter Hahn Copyright by Charles William Carter 2012 Abstract Although the 1970s was the era of U.S.-Soviet détente, the decade also saw West Germany implement its own form of détente: Ostpolitik. Trade with the Soviet Union (Osthandel) was a major feature of Ostpolitik. Osthandel, whose main feature was the development of the Soviet energy-export infrastructure, was part of a broader West German effort aimed at promoting intimate interaction with the Soviets in order to reduce tension and resolve outstanding Cold War issues. Thanks to Osthandel, West Germany became the USSR’s most important capitalist trading partner, and several oil and natural gas pipelines came into existence because of the work of such firms as Mannesmann and Thyssen. At the same time, Moscow’s growing emphasis on developing energy for exports was not a prudent move. A lack of economic diversification resulted, a development that helped devastate the USSR’s economy after the oil price collapse of 1986 and, in the process, destabilize the communist bloc. Against this backdrop, the goals of some West German Ostpolitik advocates—especially German reunification and a peaceful resolution to the Cold War—occurred. ii Dedication Dedicated to my father, Charles William Carter iii Acknowledgements This project has been several years in the making, and many individuals have contributed to its completion. -

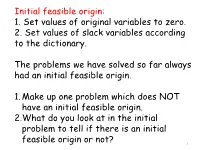

Initial Feasible Origin: 1. Set Values of Original Variables to Zero. 2. Set Values of Slack Variables According to the Dictionary

Initial feasible origin: 1. Set values of original variables to zero. 2. Set values of slack variables according to the dictionary. The problems we have solved so far always had an initial feasible origin. 1. Make up one problem which does NOT have an initial feasible origin. 2.What do you look at in the initial problem to tell if there is an initial feasible origin or not? 1 Office hours: MWR 4:20-5:30 inside or just outside Elliott 162- tell me in class that you would like to attend. For those of you who cannot stay: MWR: 1:30-2:30pm. But let me know 24 hours in advance you would like me to come in early. We will meet outside Elliott 162- Please estimate the length of time you require. I am also very happy to provide e-mail help: ([email protected]). Important note: to ensure your e-mail gets through the spam filter, use your UVic account. I answer all e-mails that I receive from my students. 2 George Dantzig: Founder of the Simplex method. http://wiki.hsc.com/wiki/Main/ConvexOptimization 3 In Dantzig’s own words: During my first year at Berkeley I arrived late one day to one of Neyman's classes. On the blackboard were two problems which I assumed had been assigned for homework. I copied them down. A few days later I apologized to Neyman for taking so long to do the homework - the problems seemed to be a little harder to do than usual. I asked him if he still wanted the work. -

![Leonid Vitaliyevich Kantorovich [Ideological Profiles of the Economics Laureates] Daniel B](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/2027/leonid-vitaliyevich-kantorovich-ideological-profiles-of-the-economics-laureates-daniel-b-2212027.webp)

Leonid Vitaliyevich Kantorovich [Ideological Profiles of the Economics Laureates] Daniel B

Leonid Vitaliyevich Kantorovich [Ideological Profiles of the Economics Laureates] Daniel B. Klein, Ryan Daza, and Hannah Mead Econ Journal Watch 10(3), September 2013: 385-388 Abstract Leonid Vitaliyevich Kantorovich is among the 71 individuals who were awarded the Sveriges Riksbank Prize in Economic Sciences in Memory of Alfred Nobel between 1969 and 2012. This ideological profile is part of the project called “The Ideological Migration of the Economics Laureates,” which fills the September 2013 issue of Econ Journal Watch. Keywords Classical liberalism, economists, Nobel Prize in economics, ideology, ideological migration, intellectual biography. JEL classification A11, A13, B2, B3 Link to this document http://econjwatch.org/file_download/734/KantorovichIPEL.pdf IDEOLOGICAL PROFILES OF THE ECONOMICS LAUREATES Shea, Christopher. 2011. Daniel Kahneman’s Politics. Ideas Market, Wall Street Journal, October 28. Link Thaler, Richard H., and Cass R. Sunstein. 2008. Nudge: Improving Decisions About Health, Wealth, and Happiness. New Haven, Conn.: Yale University Press. Leonid Vitaliyevich Kantorovich by Daniel B. Klein, Ryan Daza, and Hannah Mead Leonid V. Kantorovich (1912–1986) was born in Tsarist Russia to an affluent Jewish family; when he was 12 years old, his native city was renamed Leningrad. Kantorovich had a talent for mathematics and finished high school early at age 14 to enter Leningrad University. He graduated in 1930, then received a professorship in 1934 and finally his doctorate in mathematics in 1935 (Kantorovich 1992/1976b)—all by the age of 23. Kantorovich began his career as a mathematics professor, but forayed into economics in the late 1930s, when he began working on complex problems of resource allocation (Kantorovich 1992/1976b). -

The Mystery of Growth Mechanism in a Centrally Planned Economy: Planning Process and Economics of Shortages

Munich Personal RePEc Archive The mystery of growth mechanism in a centrally planned economy: Planning process and economics of shortages Popov, Vladimir 20 June 2020 Online at https://mpra.ub.uni-muenchen.de/101300/ MPRA Paper No. 101300, posted 02 Jul 2020 08:55 UTC The mystery of growth mechanism in a centrally planned economy: Planning process and economics of shortages Vladimir Popov ABSTRACT Since the economic calculation debate of the 1920-30s, it is known that it is impossible to create a coherent balanced plan that equates supply and demand of millions of goods and services in the national economy, not to speak about the optimal plan. It is not well understood, though, how the centrally planned economy (CPE) really functioned and what were the real determinants of their growth rates, if not the planned indicators. It was shown that forecasts of growth rates based on the extrapolation of past trends were better correlated with actual performance than planned indicators, but it is still unclear what was the real mechanism of growth of CPE and what was the role of the planning process in it. The hypothesis in this paper is that the drivers of growth in the CPE were the major investment projects initiated by the planners. They led to shortages of supplies, which triggered creeping price increases for scarce goods, which in turn boosted profitability in respective industries allowing them to increase output. De facto it was a market economy multiplier process – fiscal and monetary expansion leading to the price and output increases that eventually balanced supply and demand. -

Ideological Profiles of the Economics Laureates · Econ Journal Watch

Discuss this article at Journaltalk: http://journaltalk.net/articles/5811 ECON JOURNAL WATCH 10(3) September 2013: 255-682 Ideological Profiles of the Economics Laureates LINK TO ABSTRACT This document contains ideological profiles of the 71 Nobel laureates in economics, 1969–2012. It is the chief part of the project called “Ideological Migration of the Economics Laureates,” presented in the September 2013 issue of Econ Journal Watch. A formal table of contents for this document begins on the next page. The document can also be navigated by clicking on a laureate’s name in the table below to jump to his or her profile (and at the bottom of every page there is a link back to this navigation table). Navigation Table Akerlof Allais Arrow Aumann Becker Buchanan Coase Debreu Diamond Engle Fogel Friedman Frisch Granger Haavelmo Harsanyi Hayek Heckman Hicks Hurwicz Kahneman Kantorovich Klein Koopmans Krugman Kuznets Kydland Leontief Lewis Lucas Markowitz Maskin McFadden Meade Merton Miller Mirrlees Modigliani Mortensen Mundell Myerson Myrdal Nash North Ohlin Ostrom Phelps Pissarides Prescott Roth Samuelson Sargent Schelling Scholes Schultz Selten Sen Shapley Sharpe Simon Sims Smith Solow Spence Stigler Stiglitz Stone Tinbergen Tobin Vickrey Williamson jump to navigation table 255 VOLUME 10, NUMBER 3, SEPTEMBER 2013 ECON JOURNAL WATCH George A. Akerlof by Daniel B. Klein, Ryan Daza, and Hannah Mead 258-264 Maurice Allais by Daniel B. Klein, Ryan Daza, and Hannah Mead 264-267 Kenneth J. Arrow by Daniel B. Klein 268-281 Robert J. Aumann by Daniel B. Klein, Ryan Daza, and Hannah Mead 281-284 Gary S. Becker by Daniel B. -

H-Diplo ROUNDTABLE XXII-24

H-Diplo ROUNDTABLE XXII-24 Alan Bollard. Economists at War: How a Handful of Economists Helped Win and Lose the World Wars. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2020. ISBN: 9780198846000 (hardcover, $25.00). 1 February 2021 | https://hdiplo.org/to/RT22-24 Editor: Diane Labrosse | Production Editor: George Fujii Contents Introduction by Paul Poast, University of Chicago ........................................................................................................................... 2 Review by Laura Hein, Northwestern University .............................................................................................................................. 5 Review by Annalisa Rosselli, University of Rome Tor Vergata, Italy ............................................................................................ 8 Response by Alan Bollard, Victoria University of Wellington .....................................................................................................11 H-Diplo Roundtable XXII-24 Introduction by Paul Poast, University of Chicago ive me a one-handed economist. All my economists say, “on the one hand… on the other hand”.’ That phrase, reputedly uttered by President Harry Truman, captures the core of economics as a discipline and practice. Call it ‘G cost-benefit analysis, decision making in recognition of tradeoffs, or an ability to think ‘on the margin.’ While such practices are of value during times of peace, their importance heightens during the exigencies of war. War exacerbates the scarcity which marks everyday -

The Life Cycles of Nobel Laureates in Economics

Creative Careers: The Life Cycles of Nobel Laureates in Economics Bruce A. Weinberg & David W. Galenson De Economist Netherlands Economic Review ISSN 0013-063X Volume 167 Number 3 De Economist (2019) 167:221-239 DOI 10.1007/s10645-019-09339-9 1 23 Your article is published under the Creative Commons Attribution license which allows users to read, copy, distribute and make derivative works, as long as the author of the original work is cited. You may self- archive this article on your own website, an institutional repository or funder’s repository and make it publicly available immediately. 1 23 De Economist (2019) 167:221–239 https://doi.org/10.1007/s10645-019-09339-9 Creative Careers: The Life Cycles of Nobel Laureates in Economics Bruce A. Weinberg1 · David W. Galenson2 Published online: 26 April 2019 © The Author(s) 2019, corrected publication 2019 Abstract We identify two polar life cycles of scholarly creativity among Nobel laureate econ- omists with Tinbergen falling broadly in the middle. Experimental innovators work inductively, accumulating knowledge from experience. Conceptual innovators work deductively, applying abstract principles. Innovators whose work is more conceptual do their most important work earlier in their careers than those whose work is more experimental. Our estimates imply that the probability that the most conceptual lau- reate publishes his single best work peaks at age 25 compared to the mid-50 s for the most experimental laureate. Thus, while experience benefts experimental innova- tors, newness to a feld benefts conceptual innovators. Keywords Creativity · Life cycle · Innovation · Nobel laureates · Economics of science JEL Classifcation J240 · O300 · B310 Many scholars believe that creativity is the particular domain of the young. -

Linear Programming

LINEAR PROGRAMMING GEORGE B. DANTZIG Department of Management Science and Engineering, Stanford University, Stanford, California 94305-4023 The Story About How It Began: Some legends, a little the transportation problem was also overlooked until after about its historical significance, and comments about where others in the late 1940’s and early 1950’s had independently its many mathematical programming extensions may be rediscovered its properties. headed. What seems to characterize the pre-1947 era was lack of any interest in trying to optimize. T. Motzkin in his schol- inear programming can be viewed as part of a great arly thesis written in 1936 cites only 42 papers on linear Lrevolutionary development which has given mankind inequality systems, none of which mentioned an objective the ability to state general goals and to lay out a path of function. detailed decisions to take in order to “best” achieve its goals The major influences of the pre-1947 era were Leon- when faced with practical situations of great complexity. tief’s work on the Input-Output Model of the Economy Our tools for doing this are ways to formulate real-world (1933), an important paper by von Neumann on Game The- problems in detailed mathematical terms (models), tech- ory (1928), and another by him on steady economic growth niques for solving the models (algorithms), and engines for (1937). executing the steps of algorithms (computers and software). My own contributions grew out of my World War II This ability began in 1947, shortly after World War II, experience in the Pentagon. During the war period (1941– and has been keeping pace ever since with the extraordinary 45), I had become an expert on programming-planning growth of computing power.