The Narrative of the Scottish Nation and Its Scribal

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

New Caledonia 1698-1700: Scotland's Twice-Lost Colony

71 “New Caledonia 1698-1700: Scotland’s Twice-Lost Colony” Ignacio Gallup-Díaz, Bryn Mawr College “Lost Colonies” Conference, March 26-27, 2004 (Please do not cite, quote, or circulate without written permission from the author) This paper explores the manner in which the troubled relationship between Scotland and England played itself out in the arena of imperial expansion in the Americas. How did Scotland, a nation-state attempting to free itself from its problematic relationship with a mightier southern neighbor, act upon the colonial stage it had chosen in the Darién region of eastern Panamá? How did a nation-state that occupied the subject position in a colonial relationship itself perform as a colonizer? Informed by David Armitage’s persuasive description of the elements that differentiated the Scottish vision of empire from English expansionist thinking,1 the paper sets out to discover whether Scottish sailors, soldiers and settlers-- the individuals acting on the front lines of the nation’s expansionist effort-- interacted with the Darién’s Tule2 people in a manner that also distinguished them from their English competitors. 1. D. Armitage, “The Scottish Vision of Empire: Intellectual Origins of the Darién Venture,” in John Robertson, ed., A Union for Empire: Political Thought and the Union of 1707, (Cambridge University Press, 1995), pp. 97-121; see also his Ideological Origins of the British Empire, (Cambridge UP, 2000), pp. 158-162. 2. The San Blas Kuna Indians, the descendants of the early modern indigenous peoples of Panamá, use the word “Tule” to describe themselves, and this is the term that I shall use for the actors in this paper. -

THE KINGS and QUEENS of BRITAIN, PART I (From Geoffrey of Monmouth’S Historia Regum Britanniae, Tr

THE KINGS AND QUEENS OF BRITAIN, PART I (from Geoffrey of Monmouth’s Historia Regum Britanniae, tr. Lewis Thorpe) See also Bill Cooper’s extended version (incorporating details given by Nennius’s history and old Welsh texts, and adding hypothesised dates for each monarch, as explained here). See also the various parallel versions of the Arthurian section. Aeneas │ Ascanius │ Silvius = Lavinia’s niece │ Corineus (in Cornwall) Brutus = Ignoge, dtr of Pandrasus │ ┌─────────────┴─┬───────────────┐ Gwendolen = Locrinus Kamber (in Wales) Albanactus (in Scotland) │ └Habren, by Estrildis Maddan ┌──┴──┐ Mempricius Malin │ Ebraucus │ 30 dtrs and 20 sons incl. Brutus Greenshield └Leil └Rud Hud Hudibras └Bladud │ Leir ┌────────────────┴┬──────────────┐ Goneril Regan Cordelia = Maglaurus of Albany = Henwinus of Cornwall = Aganippus of the Franks │ │ Marganus Cunedagius │ Rivallo ┌──┴──┐ Gurgustius (anon) │ │ Sisillius Jago │ Kimarcus │ Gorboduc = Judon ┌──┴──┐ Ferrex Porrex Cloten of Cornwall┐ Dunvallo Molmutius = Tonuuenna ┌──┴──┐ Belinus Brennius = dtr of Elsingius of Norway Gurguit Barbtruc┘ = dtr of Segnius of the Allobroges └Guithelin = Marcia Sisillius┘ ┌┴────┐ Kinarius Danius = Tanguesteaia Morvidus┘ ┌──────┬────┴─┬──────┬──────┐ Gorbonianus Archgallo Elidurus Ingenius Peredurus │ ┌──┴──┐ │ │ │ (anon) Marganus Enniaunus │ Idvallo Runo Gerennus Catellus┘ Millus┘ Porrex┘ Cherin┘ ┌─────┴─┬───────┐ Fulgenius Edadus Andragius Eliud┘ Cledaucus┘ Clotenus┘ Gurgintius┘ Merianus┘ Bledudo┘ Cap┘ Oenus┘ Sisillius┘ ┌──┴──┐ Bledgabred Archmail └Redon └Redechius -

Gaelic Barbarity and Scottish Identity in the Later Middle Ages

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Enlighten MacGregor, Martin (2009) Gaelic barbarity and Scottish identity in the later Middle Ages. In: Broun, Dauvit and MacGregor, Martin(eds.) Mìorun mòr nan Gall, 'The great ill-will of the Lowlander'? Lowland perceptions of the Highlands, medieval and modern. Centre for Scottish and Celtic Studies, University of Glasgow, Glasgow, pp. 7-48. ISBN 978085261820X Copyright © 2009 University of Glasgow A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge Content must not be changed in any way or reproduced in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holder(s) When referring to this work, full bibliographic details must be given http://eprints.gla.ac.uk/91508/ Deposited on: 24 February 2014 Enlighten – Research publications by members of the University of Glasgow http://eprints.gla.ac.uk 1 Gaelic Barbarity and Scottish Identity in the Later Middle Ages MARTIN MACGREGOR One point of reasonably clear consensus among Scottish historians during the twentieth century was that a ‘Highland/Lowland divide’ came into being in the second half of the fourteenth century. The terminus post quem and lynchpin of their evidence was the following passage from the beginning of Book II chapter 9 in John of Fordun’s Chronica Gentis Scotorum, which they dated variously from the 1360s to the 1390s:1 The character of the Scots however varies according to the difference in language. For they have two languages, namely the Scottish language (lingua Scotica) and the Teutonic language (lingua Theutonica). -

Cambridge University Press 978-1-107-16336-2 — Medieval Historical Writing Edited by Jennifer Jahner , Emily Steiner , Elizabeth M

Cambridge University Press 978-1-107-16336-2 — Medieval Historical Writing Edited by Jennifer Jahner , Emily Steiner , Elizabeth M. Tyler Index More Information Index 1381 Rising. See Peasants’ Revolt Alcuin, 123, 159, 171 Alexander Minorita of Bremen, 66 Abbo of Fleury, 169 Alexander the Great (Alexander III), 123–4, Abbreviatio chronicarum (Matthew Paris), 230, 233 319, 324 Alfred of Beverley, Annales, 72, 73, 78 Abbreviationes chronicarum (Ralph de Alfred the Great, 105, 114, 151, 155, 159–60, 162–3, Diceto), 325 167, 171, 173, 174, 175, 176–7, 183, 190, 244, Abelard. See Peter Abelard 256, 307 Abingdon Apocalypse, 58 Allan, Alison, 98–9 Adam of Usk, 465, 467 Allen, Michael I., 56 Adam the Cellarer, 49 Alnwick, William, 205 Adomnán, Life of Columba, 301–2, 422 ‘Altitonantis’, 407–9 Ælfflæd, abbess of Whitby, 305 Ambrosius Aurelianus, 28, 33 Ælfric of Eynsham, 48, 152, 171, 180, 306, 423, Amis and Amiloun, 398 425, 426 Amphibalus, Saint, 325, 330 De oratione Moysi, 161 Amra Choluim Chille (Eulogy of St Lives of the Saints, 423 Columba), 287 Aelred of Rievaulx, 42–3, 47 An Dubhaltach Óg Mac Fhirbhisigh (Dudly De genealogia regum Anglorum, 325 Ferbisie or McCryushy), 291 Mirror of Charity, 42–3 anachronism, 418–19 Spiritual Friendship, 43 ancestral romances, 390, 391, 398 Aeneid (Virgil), 122 Andreas, 425 Æthelbald, 175, 178, 413 Andrew of Wyntoun, 230, 232, 237 Æthelred, 160, 163, 173, 182, 307, 311 Angevin England, 94, 390, 391, 392, 393 Æthelstan, 114, 148–9, 152, 162 Angles, 32, 103–4, 146, 304–5, 308, 315–16 Æthelthryth (Etheldrede), -

Poor Relief and the Church in Scotland, 1560−1650

George Mackay Brown and the Scottish Catholic Imagination Scottish Religious Cultures Historical Perspectives An innovative study of George Mackay Brown as a Scottish Catholic writer with a truly international reach This lively new study is the very first book to offer an absorbing history of the uncharted territory that is Scottish Catholic fiction. For Scottish Catholic writers of the twentieth century, faith was the key influence on both their artistic process and creative vision. By focusing on one of the best known of Scotland’s literary converts, George Mackay Brown, this book explores both the Scottish Catholic modernist movement of the twentieth century and the particularities of Brown’s writing which have been routinely overlooked by previous studies. The book provides sustained and illuminating close readings of key texts in Brown’s corpus and includes detailed comparisons between Brown’s writing and an established canon of Catholic writers, including Graham Greene, Muriel Spark and Flannery O’Connor. This timely book reveals that Brown’s Catholic imagination extended far beyond the ‘small green world’ of Orkney and ultimately embraced a universal human experience. Linden Bicket is a Teaching Fellow in the School of Divinity in New College, at the University of Edinburgh. She has published widely on George Mackay Brown Linden Bicket and her research focuses on patterns of faith and scepticism in the fictive worlds of story, film and theatre. Poor Relief and the Cover image: George Mackay Brown (left of crucifix) at the Italian Church in Scotland, Chapel, Orkney © Orkney Library & Archive Cover design: www.hayesdesign.co.uk 1560−1650 ISBN 978-1-4744-1165-3 edinburghuniversitypress.com John McCallum POOR RELIEF AND THE CHURCH IN SCOTLAND, 1560–1650 Scottish Religious Cultures Historical Perspectives Series Editors: Scott R. -

Inchmahome Priory Statement of Significance

Property in Care (PIC) ID:PIC073 Designations: Scheduled Monument (SM90169); Gardens and Designed Landscapes (GDL00218) Taken into State care: 1926 (Guardianship) Last reviewed: 2012 STATEMENT OF SIGNIFICANCE INCHMAHOME PRIORY We continually revise our Statements of Significance, so they may vary in length, format and level of detail. While every effort is made to keep them up to date, they should not be considered a definitive or final assessment of our properties. Historic Environment Scotland – Scottish Charity No. SC045925 Principal Office: Longmore House, Salisbury Place, Edinburgh EH9 1SH © Historic Environment Scotland 2019 You may re-use this information (excluding logos and images) free of charge in any format or medium, under the terms of the Open Government Licence v3.0 except where otherwise stated. To view this licence, visit http://nationalarchives.gov.uk/doc/open- government-licence/version/3/ or write to the Information Policy Team, The National Archives, Kew, London TW9 4DU, or email: [email protected] Where we have identified any third party copyright information you will need to obtain permission from the copyright holders concerned. Any enquiries regarding this document should be sent to us at: Historic Environment Scotland Longmore House Salisbury Place Edinburgh EH9 1SH +44 (0) 131 668 8600 www.historicenvironment.scot You can download this publication from our website at www.historicenvironment.scot Historic Environment Scotland – Scottish Charity No. SC045925 Principal Office: Longmore House, Salisbury Place, Edinburgh EH9 1SH INCHMAHOME PRIORY SYNOPSIS Inchmahome Priory nestles on the tree-clad island of Inchmahome, in the Lake of Menteith. It was founded by Walter Comyn, 4th Earl of Menteith, c.1238, though there was already a religious presence on the island. -

Catalogue Description and Inventory

= CATALOGUE DESCRIPTION AND INVENTORY Adv.MSS.30.5.22-3 Hutton Drawings National Library of Scotland Manuscripts Division George IV Bridge Edinburgh EH1 1EW Tel: 0131-466 2812 Fax: 0131-466 2811 E-mail: [email protected] © 2003 Trustees of the National Library of Scotland = Adv.MSS.30.5.22-23 HUTTON DRAWINGS. A collection consisting of sketches and drawings by Lieut.-General G.H. Hutton, supplemented by a large number of finished drawings (some in colour), a few maps, and some architectural plans and elevations, professionally drawn for him by others, or done as favours by some of his correspondents, together with a number of separately acquired prints, and engraved views cut out from contemporary printed books. The collection, which was previously bound in two large volumes, was subsequently dismounted and the items individually attached to sheets of thick cartridge paper. They are arranged by county in alphabetical order (of the old manner), followed by Orkney and Shetland, and more or less alphabetically within each county. Most of the items depict, whether in whole or in part, medieval churches and other ecclesiastical buildings, but a minority depict castles or other secular dwellings. Most are dated between 1781 and 1792 and between 1811 and 1820, with a few of earlier or later date which Hutton acquired from other sources, and a somewhat larger minority dated 1796, 1801-2, 1805 and 1807. Many, especially the engravings, are undated. For Hutton’s notebooks and sketchbooks, see Adv.MSS.30.5.1-21, 24-26 and 28. For his correspondence and associated papers, see Adv.MSS.29.4.2(i)-(xiii). -

St Margaret of Scotland, Morgan Colman's

2021 VIII The Saxon Connection: St Margaret of Scotland, Morgan Colman’s Genealogies, and James VI & I’s Anglo-Scottish Union Project Joseph B. R. Massey Article: The Saxon Connection: St Margaret of Scotland, Morgan Colman’s Genealogies, and James VI & I’s Anglo-Scottish Union Project The Saxon Connection: St Margaret of Scotland, Morgan Colman’s Genealogies, and James VI & I’s Anglo-Scottish Union Project Joseph B.R. Massey MANCHESTER METROPOLITAN UNIVERSITY Abstract: James VI of Scotland’s succession to the English throne as James I in 1603 was usually justified by contemporaries on the grounds that James was Henry VII’s senior surviving descendant, making him the rightful hereditary claimant. Some works, however, argued that James also had the senior Saxon hereditary claim to the English throne due his descent from St Margaret of Scotland—making his hereditary claim superior to that of any English monarch from William the Conqueror onwards. Morgan Colman’s Arbor Regalis, a large and impressive genealogy, was a visual assertion of this argument, showing that James’s senior hereditary claims to the thrones of both England and Scotland went all the way back to the very foundations of the two kingdoms. This article argues that Colman’s genealogy could also be interpreted in support of James’s Anglo-Scottish union project, showing that the permanent union of England and Scotland as Great Britain was both historically legitimate and a justifiable outcome of James’s combined hereditary claims. Keywords: Jacobean; genealogies; Great Britain; hereditary right; succession n 24 March 1603, Queen Elizabeth I of England died and her Privy Council proclaimed that James VI, King of Scots, had succeeded as King of England. -

Chap 2 Broun

222 Attitudes of Gall to Gaedhel in Scotland before John of Fordun DAUVIT BROUN It is generally held that the idea of Scotland’s division between Gaelic ‘Highlands’ and Scots or English ‘Lowlands’ can be traced no further back than the mid- to late fourteenth century. One example of the association of the Gaelic language with the highlands from this period is found in Scalacronica (‘Ladder Chronicle’), a chronicle in French by the Northumbrian knight, Sir Thomas Grey. Grey and his father had close associations with Scotland, and so he cannot be treated simply as representing an outsider’s point of view. 1 His Scottish material is likely to have been written sometime between October 1355 and October 1359.2 He described how the Picts had no wives and so acquired them from Ireland, ‘on condition that their offspring would speak Irish, which language remains to this day in the highlands among those who are called Scots’. 3 There is also an example from the ‘Highlands’ themselves. In January 1366 the papacy at Avignon issued a mandate to the bishop of Argyll granting Eoin Caimbeul a dispensation to marry his cousin, Mariota Chaimbeul. It was explained (in words which, it might be expected, 1See especially Alexander Grant, ‘The death of John Comyn: what was going on?’, SHR 86 (2007) 176–224, at 207–9. 2He began to work sometime in or after 1355 while he was a prisoner in Edinburgh Castle, and finished the text sometime after David II’s second marriage in April 1363 (the latest event noted in the work); but he had almost certainly finished this part of the chronicle before departing for France in 1359: see Sir Thomas Gray, Scalacronica, 1272–1363 , ed. -

A Welsh Classical Dictionary

A WELSH CLASSICAL DICTIONARY DACHUN, saint of Bodmin. See s.n. Credan. He has been wrongly identified with an Irish saint Dagan in LBS II.281, 285. G.H.Doble seems to have been misled in the same way (The Saints of Cornwall, IV. 156). DAGAN or DANOG, abbot of Llancarfan. He appears as Danoc in one of the ‘Llancarfan Charters’ appended to the Life of St.Cadog (§62 in VSB p.130). Here he is a clerical witness with Sulien (presumably abbot) and king Morgan [ab Athrwys]. He appears as abbot of Llancarfan in five charters in the Book of Llandaf, where he is called Danoc abbas Carbani Uallis (BLD 179c), and Dagan(us) abbas Carbani Uallis (BLD 158, 175, 186b, 195). In these five charters he is contemporary with bishop Berthwyn and Ithel ap Morgan, king of Glywysing. He succeeded Sulien as abbot and was succeeded by Paul. See Trans.Cym., 1948 pp.291-2, (but ignore the dates), and compare Wendy Davies, LlCh p.55 where Danog and Dagan are distinguished. Wendy Davies dates the BLD charters c.A.D.722 to 740 (ibid., pp.102 - 114). DALLDAF ail CUNIN COF. (Legendary). He is included in the tale of ‘Culhwch and Olwen’ as one of the warriors of Arthur's Court: Dalldaf eil Kimin Cof (WM 460, RM 106). In a triad (TYP no.73) he is called Dalldaf eil Cunyn Cof, one of the ‘Three Peers’ of Arthur's Court. In another triad (TYP no.41) we are told that Fferlas (Grey Fetlock), the horse of Dalldaf eil Cunin Cof, was one of the ‘Three Lovers' Horses’ (or perhaps ‘Beloved Horses’). -

Download Download

II.—An Account of St Columbd's Abbey, Inchcolm. Accompanied with Plans, ^c.1 (Plates IV.-VL) By THOMAS ARNOLD, Esq., Architect, M.R.LB.A, Lond. [Communicated January 11, 1869, with an Introductory Note.] NEAR the northern shores of the Firth of Forth, and within sight of Edin- burgh, lies the island anciently known as Emona, and in later times as Inchcolm, the island of St Columba. It is of very small extent, scarcely over half a mile in length, and 400 feet in width at its broadest part. The tide of commerce and busy life which ebbs and flows around has left the little inch in a solitude as profound as if it gemmed the bosom of some Highland loch, a solitude which impresses itself deeply on the stranger who comes to gaze on its ruined, deserted, and forgotten Abbey. Few even of those who visit the island from the beautiful village of Aberdour, close to it, know anything of its history, and as few out of sight of the island know of its existence at all. But although now little known beyond the shores of the Forth, Inchcolm formerly held a high place in the veneration of the Scottish people as the cradle of the religious life of the surrounding districts, and was second only to lona as a holy isle in whose sacred soil it was the desire of many generations to be buried. It numbered amongst its abbots men of high position and learning. Noble benefactors enriched it with broad lands and rich gifts, and its history and remains, like the strata of some old mountain, bear the marks of every great wave of life which has passed over our country. -

Converted by Filemerlin

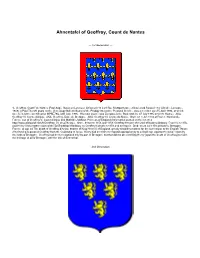

Ahnentafel of Geoffroy, Count de Nantes --- 1st Generation --- 1. Geoffroy, Count1 de Nantes (Paul Augé, Nouveau Larousse Universel (13 à 21 Rue Montparnasse et Boulevard Raspail 114: Librairie Larousse, 1948).) (Paul Theroff, posts on the Genealogy Bulletin Board of the Prodigy Interactive Personal Service, was a member as of 5 April 1994, at which time he held the identification MPSE79A, until July, 1996. His main source was Europaseische Stammtafeln, 07 July 1995 at 00:30 Hours.). AKA: Geoffroy VI, Comte d'Anjou. AKA: Geoffroy, Duke de Bretagne. AKA: Geoffroy VI, Comte du Maine. Born: on 3 Jun 1134 at Rouen, Normandie, France, son of Geoffroy V, Count d'Anjou and Mathilde=Mahaut, Princess of England (Information posted on the Internet, http://www.wikiwand.com/fr/Geoffroy_VI_d%27Anjou.). Note - between 1156 and 1158: Geoffroy became the Lord of Nantes (Brittany, France) in 1156, and Henry II his brother claimed the overlordship of Brittany on Geoffrey's death in 1158 and overran it. Died: on 26 Jul 1158 at Nantes, Bretagne, France, at age 24 The death of Geoffroy d'Anjou, brother of King Henry II of England, greatly simplifies matters for the succession to the English Throne. After having separated Geoffroy from the Countship of Anjou, Henry had sent him to respond appropriatetly to a challenge against the ducal crown by the lords of Bretagne. Geoffroy had been recognized only by part of Bretagne, but that did not prevent King Henry [upon the death of Geoffroy] to claim the heritage of all of Bretagne, with the title of Seneschal. --- 2nd Generation --- Coat of Arm associated with Geoffroy V, Comte d'Anjou.