Central Banking Challenges Posed by Uncertain Climate Change and Natural Disasters∗

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Monetary History of the United States, 1867-1960’

JOURNALOF Monetary ECONOMICS ELSEVIER Journal of Monetary Economics 34 (I 994) 5- 16 Review of Milton Friedman and Anna J. Schwartz’s ‘A monetary history of the United States, 1867-1960’ Robert E. Lucas, Jr. Department qf Economics, University of Chicago, Chicago, IL 60637, USA (Received October 1993; final version received December 1993) Key words: Monetary history; Monetary policy JEL classijcation: E5; B22 A contribution to monetary economics reviewed again after 30 years - quite an occasion! Keynes’s General Theory has certainly had reappraisals on many anniversaries, and perhaps Patinkin’s Money, Interest and Prices. I cannot think of any others. Milton Friedman and Anna Schwartz’s A Monetary History qf the United States has become a classic. People are even beginning to quote from it out of context in support of views entirely different from any advanced in the book, echoing the compliment - if that is what it is - so often paid to Keynes. Why do people still read and cite A Monetary History? One reason, certainly, is its beautiful time series on the money supply and its components, extended back to 1867, painstakingly documented and conveniently presented. Such a gift to the profession merits a long life, perhaps even immortality. But I think it is clear that A Monetary History is much more than a collection of useful time series. The book played an important - perhaps even decisive - role in the 1960s’ debates over stabilization policy between Keynesians and monetarists. It organ- ized nearly a century of U.S. macroeconomic evidence in a way that has had great influence on subsequent statistical and theoretical research. -

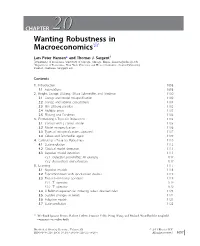

CHAPTER 2020 Wanting Robustness in Macroeconomics$

CHAPTER 2020 Wanting Robustness in Macroeconomics$ Lars Peter Hansen* and Thomas J. Sargent{ * Department of Economics, University of Chicago, Chicago, Illinois. [email protected] { Department of Economics, New York University and Hoover Institution, Stanford University, Stanford, California. [email protected] Contents 1. Introduction 1098 1.1 Foundations 1098 2. Knight, Savage, Ellsberg, Gilboa-Schmeidler, and Friedman 1100 2.1 Savage and model misspecification 1100 2.2 Savage and rational expectations 1101 2.3 The Ellsberg paradox 1102 2.4 Multiple priors 1103 2.5 Ellsberg and Friedman 1104 3. Formalizing a Taste for Robustness 1105 3.1 Control with a correct model 1105 3.2 Model misspecification 1106 3.3 Types of misspecifications captured 1107 3.4 Gilboa and Schmeidler again 1109 4. Calibrating a Taste for Robustness 1110 4.1 State evolution 1112 4.2 Classical model detection 1113 4.3 Bayesian model detection 1113 4.3.1 Detection probabilities: An example 1114 4.3.2 Reservations and extensions 1117 5. Learning 1117 5.1 Bayesian models 1118 5.2 Experimentation with specification doubts 1119 5.3 Two risk-sensitivity operators 1119 5.3.1 T1 operator 1119 5.3.2 T2 operator 1120 5.4 A Bellman equation for inducing robust decision rules 1121 5.5 Sudden changes in beliefs 1122 5.6 Adaptive models 1123 5.7 State prediction 1125 $ We thank Ignacio Presno, Robert Tetlow, Franc¸ois Velde, Neng Wang, and Michael Woodford for insightful comments on earlier drafts. Handbook of Monetary Economics, Volume 3B # 2011 Elsevier B.V. ISSN 0169-7218, DOI: 10.1016/S0169-7218(11)03026-7 All rights reserved. -

Pricing Uncertainty Induced by Climate Change∗

Pricing Uncertainty Induced by Climate Change∗ Michael Barnett William Brock Lars Peter Hansen Arizona State University University of Wisconsin University of Chicago and University of Missouri January 30, 2020 Abstract Geophysicists examine and document the repercussions for the earth’s climate induced by alternative emission scenarios and model specifications. Using simplified approximations, they produce tractable characterizations of the associated uncer- tainty. Meanwhile, economists write highly stylized damage functions to speculate about how climate change alters macroeconomic and growth opportunities. How can we assess both climate and emissions impacts, as well as uncertainty in the broadest sense, in social decision-making? We provide a framework for answering this ques- tion by embracing recent decision theory and tools from asset pricing, and we apply this structure with its interacting components to a revealing quantitative illustration. (JEL D81, E61, G12, G18, Q51, Q54) ∗We thank James Franke, Elisabeth Moyer, and Michael Stein of RDCEP for the help they have given us on this paper. Comments, suggestions and encouragement from Harrison Hong and Jose Scheinkman are most appreciated. We gratefully acknowledge Diana Petrova and Grace Tsiang for their assistance in preparing this manuscript, Erik Chavez for his comments, and Jiaming Wang, John Wilson, Han Xu, and especially Jieyao Wang for computational assistance. More extensive results and python scripts are avail- able at http://github.com/lphansen/Climate. The Financial support for this project was provided by the Alfred P. Sloan Foundation [grant G-2018-11113] and computational support was provided by the Research Computing Center at the University of Chicago. Send correspondence to Lars Peter Hansen, University of Chicago, 1126 E. -

ΒΙΒΛΙΟΓ ΡΑΦΙΑ Bibliography

Τεύχος 53, Οκτώβριος-Δεκέμβριος 2019 | Issue 53, October-December 2019 ΒΙΒΛΙΟΓ ΡΑΦΙΑ Bibliography Βραβείο Νόμπελ στην Οικονομική Επιστήμη Nobel Prize in Economics Τα τεύχη δημοσιεύονται στον ιστοχώρο της All issues are published online at the Bank’s website Τράπεζας: address: https://www.bankofgreece.gr/trapeza/kepoe https://www.bankofgreece.gr/en/the- t/h-vivliothhkh-ths-tte/e-ekdoseis-kai- bank/culture/library/e-publications-and- anakoinwseis announcements Τράπεζα της Ελλάδος. Κέντρο Πολιτισμού, Bank of Greece. Centre for Culture, Research and Έρευνας και Τεκμηρίωσης, Τμήμα Documentation, Library Section Βιβλιοθήκης Ελ. Βενιζέλου 21, 102 50 Αθήνα, 21 El. Venizelos Ave., 102 50 Athens, [email protected] Τηλ. 210-3202446, [email protected], Tel. +30-210-3202446, 3202396, 3203129 3202396, 3203129 Βιβλιογραφία, τεύχος 53, Οκτ.-Δεκ. 2019, Bibliography, issue 53, Oct.-Dec. 2019, Nobel Prize Βραβείο Νόμπελ στην Οικονομική Επιστήμη in Economics Συντελεστές: Α. Ναδάλη, Ε. Σεμερτζάκη, Γ. Contributors: A. Nadali, E. Semertzaki, G. Tsouri Τσούρη Βιβλιογραφία, αρ.53 (Οκτ.-Δεκ. 2019), Βραβείο Nobel στην Οικονομική Επιστήμη 1 Bibliography, no. 53, (Oct.-Dec. 2019), Nobel Prize in Economics Πίνακας περιεχομένων Εισαγωγή / Introduction 6 2019: Abhijit Banerjee, Esther Duflo and Michael Kremer 7 Μονογραφίες / Monographs ................................................................................................... 7 Δοκίμια Εργασίας / Working papers ...................................................................................... -

Hansen & Sargent 1980

Journal of Economic Dynamics and Control 2 (1980) 7-46. 0 North-Holland FORMULATING AND ESTIMATING DYNAMIC LINEAR RATIONAL EXPECTATIONS MODELS* Lars Peter HANSEN Carnegie-Mellon University, Pittsburgh, PA 15213, USA Thomas J. SARGENT University of Minnesota, and Federal Reserve Bank, Minneapolis, MN 55455, USA This paper describes methods for conveniently formulating and estimating dynamic linear econometric models under the hypothesis of rational expectations. An econometrically con- venient formula for the cross-equation rational expectations restrictions is derived. Models of error terms and the role of the concept of Granger causality in formulating rational expectations models are both discussed. Tests of the hypothesis of strict econometric exogeneity along the lines of Sims’s are compared with a test that is related to Wu’s. 1. Introduction This paper describes research which aims to provide tractable procedures for combining econometric methods with dynamic economic theory for the purpose of modeling and interpreting economic time series. That we are short of such methods was a message of Lucas’ (1976) criticism of procedures for econometric policy evaluation. Lucas pointed out that agents’ decision rules, e.g., dynamic demand and supply schedules, are predicted by economic theory to vary systematically with changes in the stochastic processes facing agents. This is true according to virtually any dynamic theory that attributes some degree of rationality to economic agents, e.g., various versions of ‘rational expectations’ and ‘Bayesian learning’ hypotheses. The implication of Lucas’ observation is that instead of estimating the parameters of decision rules, what should be estimated are the parameters of agents’ objective functions and of the random processes that they faced historically. -

Silver Moon Or Golden Star: a Conversation About Utopia (Dec 10) Special Event with Nobel Laureate Lars Peter Hansen (Dec 10) Ec

Subscribe E-News December 2019 Issue 1 Silver Moon or Golden Star: A Conversation about Utopia (Dec 10) Loosely taking the idealism displayed at the 1933 World’s Fair in Chicago as a point of departure, multimedia artist Samson Young will discuss his current exhibition Silver Moon or Golden Star: Which will you buy of me? at the Smart Museum of Art at the University of Chicago, which asks how people adapt to societal changes that they have little control over. Details Special Event with Nobel Laureate Lars Peter Hansen (Dec 10) Join us for a special event in Shanghai with Nobel Laureate Lars Peter Hansen who will discuss "Climate Change: Uncertainty and Economic Policy". Lars Peter Hansen is a leading expert in economic dynamics who works at the forefront of economic thinking and modeling, drawing approaches from macroeconomics, finance, and statistics. Chicago Booth and UChicago alumni and students are welcome. Details Economic Outlook 2020: Big Tech, Trade, and the Future of the Economy (Jan 15) Big Tech companies are changing the face of the global financial markets, creating one of the biggest challenges since the financial crisis. How are central banks around the world grappling with fast-changing technology? What does the shift mean for the global economy, regulations, and markets? Will escalating trade wars tip the world into recession or will the long expansion continue? Join Booth professors Randall S. Kroszner and Brent Neiman along with Yue Chim Richard Wong for Economic Outlook 2020 in Hong Kong to discuss the state of the global economy and gain insights into the year ahead. -

The Midway and Beyond: Recent Work on Economics at Chicago Douglas A

The Midway and Beyond: Recent Work on Economics at Chicago Douglas A. Irwin Since its founding in 1892, the University of Chicago has been home to some of the world’s leading economists.1 Many of its faculty members have been an intellectual force in the economics profession and some have played a prominent role in public policy debates over the past half-cen- tury.2 Because of their impact on the profession and inuence in policy Correspondence may be addressed to: Douglas Irwin, Department of Economics, Dartmouth College, Hanover, NH 03755; email: [email protected]. I am grateful to Dan Ham- mond, Steve Medema, David Mitch, Randy Kroszner, and Roy Weintraub for very helpful com- ments and advice; all errors, interpretations, and misinterpretations are solely my own. Disclo- sure: I was on the faculty of the then Graduate School of Business at the University of Chicago in the 1990s and a visiting professor at the Booth School of Business in the fall of 2017. 1. To take a crude measure, nearly a dozen economists who spent most of their career at Chicago have won the Nobel Prize, or, more accurately, the Sveriges Riksbank Prize in Eco- nomic Sciences in Memory of Alfred Nobel. The list includes Milton Friedman (1976), Theo- dore W. Schultz (1979), George J. Stigler (1982), Merton H. Miller (1990), Ronald H. Coase (1991), Gary S. Becker (1992), Robert W. Fogel (1993), Robert E. Lucas, Jr. (1995), James J. Heckman (2000), Eugene F. Fama and Lars Peter Hansen (2013), and Richard H. Thaler (2017). This list excludes Friedrich Hayek, who did his prize work at the London School of Economics and only spent a dozen years at Chicago. -

Inside the Economist's Mind: the History of Modern

1 Inside the Economist’s Mind: The History of Modern Economic Thought, as Explained by Those Who Produced It Paul A. Samuelson and William A. Barnett (eds.) CONTENTS Foreword: Reflections on How Biographies of Individual Scholars Can Relate to a Science’s Biography Paul A. Samuelson Preface: An Overview of the Objectives and Contents of the Volume William A. Barnett History of Thought Introduction: Economists Talking with Economists, An Historian’s Perspective E. Roy Weintraub INTERVIEWS Chapter 1 An Interview with Wassily Leontief Interviewed by Duncan K. Foley Chapter 2 An Interview with David Cass Interviewed jointly by Steven E. Spear and Randall Wright Chapter 3 An Interview with Robert E. Lucas, Jr. Interviewed by Bennett T. McCallum Chapter 4 An Interview with Janos Kornai Interviewed by Olivier Blanchard Chapter 5 An Interview with Franco Modigliani Interviewed by William A. Barnett and Robert Solow Chapter 6 An Interview with Milton Friedman Interviewed by John B. Taylor Chapter 7 An Interview with Paul A. Samuelson Interviewed by William A. Barnett Chapter 8 An Interview with Paul A. Volcker Interviewed by Perry Mehrling 2 Chapter 9 An Interview with Martin Feldstein Interviewed by James M. Poterba Chapter 10 An Interview with Christopher A. Sims Interviewed by Lars Peter Hansen Chapter 11 An Interview with Robert J. Shiller Interviewed by John Y. Campbell Chapter 12 An Interview with Stanley Fischer Interviewed by Olivier Blanchard Chapter 13 From Uncertainty to Macroeconomics and Back: An Interview with Jacques Drèze Interviewed by Pierre Dehez and Omar Licandro Chapter 14 An Interview with Tom J. Sargent Interviewed by George W. -

Alibaba Initiates the Open Research Platform “Luohan Academy”

Alibaba Initiates the Open Research Platform “Luohan Academy” Six Nobel Laureates, other top international minds to address societal changes arising from digital technologies Hangzhou, China, June 27, 2018 – Alibaba Group Holding Limited (“Alibaba Group”) (NYSE: BABA) has advocated the establishment of the “Luohan Academy” (“Academy”), an open research platform with Nobel Laureates and leading international social scientists to address universal challenges faced by societies arising from the rapid development of digital technologies. The Luohan Academy complements Alibaba’s DAMO Academy, a global research program established last October with a focus on developing cutting-edge technologies. Digital technologies are fundamentally changing markets and economies with the potential to improve mankind's prospects in many ways. The Luohan Academy will focus on examining the implications that technologies will bring to the societies in the future. “The advancement of technology is coming at us at dazzling speed and it has changed almost every aspect of human society. So when we look at the benefits from technology, it is equally important to understand the challenges we faced and how we can work together to address them,” said Jack Ma, Executive Chairman of Alibaba Group. “We feel the obligation to use our technology, our resources, our people and everything we have to help societies embrace the technological transformation and its implications. This is why we initiated an open and collaborative research platform, the Luohan Academy, and invite top international thinkers to join this collaboration,” added Ma. During the first conference held in Hangzhou this week, the committee of the Luohan Academy convened and signed the mission statement. -

Browse the Program from the Conference

Research and Policy: A Golden Minnesota Partnership ound economic research is the bedrock of solid economic policy. A CELEBRATION Great research, in turn, is often inspired by confronting key policy Sissues in a supportive and independent environment. This conference OF INTELLECTUAL honors an intellectual revolution galvanized by bringing these elements to- gether a half century ago and launching a remarkable relationship between INDEPENDENCE the Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis and the University of Minnesota. This alliance transformed how economists conduct research and how AND COLLEGIAL policy is made. In a sense, it was modeled on the close bond between Walter Heller, the COOPERATION policy-oriented chair of the Council of Economic Advisers under President John F. Kennedy, and Leonid Hurwicz, the brilliant theoretician and future Nobel laureate. They built the University’s world-class economics department that joined with Fed policymakers in the late 1960s to develop better forecasting models, an effort soon usurped by the then-radical theory of rational expectations. What followed were research and policy ranging from time consistency to early childhood education, from sovereign debt to distributional inequality, from real business cycles to too big to fail. And, along the way, improvements in forecasting—the spark that began it all. We’ve convened to review lessons learned over the past 50 years about successful policy-academia collaboration and to explore current research that will shape the theory and practice of economics over the next 50 years. This is a celebration of all involved, past and present, and of the spirit of intellectual independence and collegial cooperation that lies at the heart of the partnership. -

Systemic Risk and Macro Modeling

This PDF is a selecon from a published volume from the Naonal Bureau of Economic Research Volume Title: Risk Topography: Systemic Risk and Macro Modeling Volume Author/Editor: Markus Brunnermeier and Arvind Krishnamurthy, editors Volume Publisher: University of Chicago Press Volume ISBN: 0‐226‐07773‐X (cloth); 978‐0‐226‐07773‐4 (cloth); 978‐0‐226‐09264‐5 (eISBN) Volume URL: hp://www.nber.org/books/brun11‐1 Conference Date: April 28, 2011 Publicaon Date: August 2014 Chapter Title: Challenges in Idenfying and Measuring Systemic Risk Chapter Author(s): Lars Peter Hansen Chapter URL: hp://www.nber.org/chapters/c12507 Chapter pages in book: (p. 15 ‐ 30) 1 Challenges in Identifying and Measuring Systemic Risk Lars Peter Hansen 1.1 Introduction Discussions of public oversight of financial markets often make reference to “systemic risk” as a rationale for prudent policy making. For example, mitigating systemic risk is a common defense underlying the need for mac- roprudential policy initiatives. The term has become a grab bag, and its lack of specificity could undermine the assessment of alternative policies. At the outset of this essay I ask, should systemic risk be an explicit target of mea- surement, or should it be relegated to being a buzz word, a slogan or a code word used to rationalize regulatory discretion? I remind readers of the dictum attributed to Sir William Thomson (Lord Kelvin): I often say that when you can measure something that you are speaking about, express it in numbers, you know something about it; but when you cannot measure it, when you cannot express it in numbers, your knowl- edge is of the meagre and unsatisfactory kind: it may be the beginning of knowledge, but you have scarcely, in your thoughts advanced to the stage of science, whatever the matter might be.1 Lars Peter Hansen is the David Rockefeller Distinguished Service Professor in Economics, Statistics, and the College at the University of Chicago and a research associate of the National Bureau of Economic Research. -

Theories of Fairness and Reciprocity - Evidence and Economic Applications∗

Theories of Fairness and Reciprocity - ∗ Evidence and Economic Applications Ernst Fehra) University of Zurich and CEPR Klaus M. Schmidtb) University of Munich and CEPR Published in: Mathias Dewatripont, Lars Peter Hansen and Stephen J Turnovsky (2003): Advances in Economics and Econometrics, Econometric Society Monographs, Eighth World Congress, Volume 1, pp 208 – 257. Abstract: Most economic models are based on the self-interest hypothesis that assumes that all people are exclusively motivated by their material self-interest. In recent years experimental economists have gathered overwhelming evidence that systematically refutes the self-interest hypothesis and suggests that many people are strongly motivated by concerns for fairness and reciprocity. Moreover, several theoretical papers have been written showing that the observed phenomena can be explained in a rigorous and tractable manner. These theories in turn induced a new wave of experimental research offering additional exciting insights into the nature of preferences and into the relative performance of competing theories of fairness. The purpose of this paper is to review these recent developments, to point out open questions, and to suggest avenues for future research. JEL classification numbers: C7, C9, D0, J3. Keywords: Behavioral Economics, Fairness, Reciprocity, Altruism, Experiments, Incentives, Contracts, Competition ∗ We would like to thank Glenn Ellison for many helpful comments and suggestions and Alexander Klein and Susanne Kremhelmer for excellent research assistance. Part of this research was conducted while the second author visited Stanford University and he would like to thank the Economics Department for its great hospitality. Financial support by Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft through grant SCHM-1196/4-1 is gratefully acknowledged.