Juror Misconduct in the Digital Age

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Apachecon US 2008 with Apache Shindig

ApacheCon US 2008 Empowering the social web with Apache Shindig Henning Schmiedehausen Sr. Software Engineer – Ning, Inc. November 3 - 7 • New Orleans Leading the Wave of Open Source The Official User Conference of The Apache Software Foundation Freitag, 7. November 2008 1 • How the web became social • Get out of the Silo – Google Gadgets • OpenSocial – A social API • Apache Shindig • Customizing Shindig • Summary November 3 - 7 • New Orleans ApacheCon US 2008 Leading the Wave of Open Source The Official User Conference of The Apache Software Foundation Freitag, 7. November 2008 2 ApacheCon US 2008 In the beginning... Freitag, 7. November 2008 3 ApacheCon US 2008 ...let there be web 2.0 Freitag, 7. November 2008 4 • Web x.0 is about participation • Users have personalized logins Relations between users are graphs • "small world phenomenon", "six degrees of separation", Erdös number, Bacon number November 3 - 7 • New Orleans ApacheCon US 2008 Leading the Wave of Open Source The Official User Conference of The Apache Software Foundation Freitag, 7. November 2008 5 ApacheCon US 2008 The Silo problem Freitag, 7. November 2008 6 • How the web became social • Get out of the Silo – Google Gadgets • OpenSocial – A social API • Apache Shindig • Customizing Shindig • Summary November 3 - 7 • New Orleans ApacheCon US 2008 Leading the Wave of Open Source The Official User Conference of The Apache Software Foundation Freitag, 7. November 2008 7 ApacheCon US 2008 iGoogle Freitag, 7. November 2008 8 • Users adds Gadgets to their homepages Gadgets share screen space • Google experiments with Canvas view Javascript, HTML, CSS • A gadget runs on the Browser! Predefined Gadgets API • Core APIs for IO, JSON, Prefs; optional APIs (e.g. -

Creating a Simple Website

TUTORIAL Creating a Simple Website Why having a website? Table of Contents Table of Contents .................................................................................................................................... 2 Step 1: create a Google account (Gmail) ................................................................................................. 3 Step 2: create a Google website .............................................................................................................. 4 Step 3: edit a page ................................................................................................................................... 6 Add an hyperlink ................................................................................................................................. 7 Create a new page: .............................................................................................................................. 8 Add an image....................................................................................................................................... 9 Step 4: website page setting .................................................................................................................. 10 The header ......................................................................................................................................... 10 The side bar ...................................................................................................................................... -

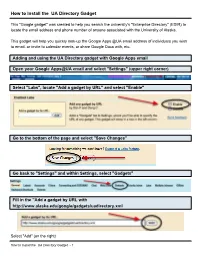

How to Install the UA Directory Gadget

How to Install the UA Directory Gadget This "Google gadget" was created to help you search the university's "Enterprise Directory" (EDIR) to locate the email address and phone number of anyone associated with the University of Alaska. This gadget will help you quickly look-up the Google Apps @UA email address of individuals you wish to email, or invite to calendar events, or share Google Docs with, etc. Adding and using the UA Directory gadget with Google Apps email Open your Google Apps@UA email and select "Settings" (upper right corner) Select "Labs", locate "Add a gadget by URL" and select "Enable" Go to the bottom of the page and select "Save Changes" Go back to "Settings" and within Settings, select "Gadgets" Fill in the "Add a gadget by URL with http://www.alaska.edu/google/gadgets/uadirectory.xml Select "Add" (on the right) How to Install the UA Directory Gadget - 1 In your Gadgets section you should see the following If you go back into your email on the left side you should now see the UA Directory Click on the "+" sign to expand the search box At this point, you have the option to authorize the gadget to access your contacts. If you decide to allow access, you will the option of adding the result from the search into your contacts - you will see "Add to Contact". This does not allow access to your account's contacts by anyone else or by any other application. If you choose to not authorize the gadget, the "Add to Contact" link will not be available in the search results. -

Google Sites & Apps Keith Warne

Google Sites & Apps How to guide Keith Warne Contents 1. Opening your Google account 2. Creating your Google site 3. Editing your site 4. Managing your site 5. Opening your Google account: 1.1 Navigate to “sites.google.com” 1.2 Select – “Create a google account” 1.3 Enter details required – choose a gmail account and email name. 1.4 Upload a photo (if you like) 1.5 You now have a google account: Navigate back to Google Sites 2 Creating Your WebSite 2.1 On the Google Sites page select “CREATE” 2.2 Name your site, select a theme (Classroom) and choose a theme. Most of these can be changed at a later stage. You can put in a description of the site and then need to enter the security code as well. Link to my class site blank: https://sites.google.com/site/classsiteblank/ Select “CREATE” 3 Editing your Class Site. You now have a basic website and can set about changing it. The icons on the top of the page give access to the options for editing, adding pages and managing the site. Edit page Add New Page More Options Menu 3.1 Edit page options Clicking on the “Edit Page” button opens the following editing options: Insert, Format, Table, Layout and Help. These allow the usual editing functions that you would find in a word document and function in much the same way. Shortcut icons are also shown which allow faster editing. Text style, colour, and formatting all work as expected and the save button above allows you to keep your changes. -

Google Acks First Edition

RflCKSl Google acks First Edition Philipp Lenssen O'REILLT BEIJING • CAMBRIDGE • FARNHAM • KÖLN • PARIS • SEBASTOPOL • TAIPEI • TOKYO :;:;; »p;;;» mmm ;*. ^ P;i?|p:*: JK*S,. FOREWORD xi PREFACE xiii Google's Apps—a Google Office, or a Google OS? xiii How to Use This Book xiv HowThis Book Is Organized xiv Conventions Used in This Book xvi Acknowledgments xvi We'd Like to Hear from You xvii CHAPTER Ol: MEETTHE GOOGLE DOCS FAMILY 2 HACK oi: How to Get Your Google Account 2 HACK 02: Collaborate with OthersThrough Google Docs 5 HACK 03: Make a Desktop Icon to Create a New Document 9 HACK 04: Embed a Dynamic Chart into a Google Document or a Web Page 12 HACK 05: Share Documents with a Group 16 HACK 06: Automatically Open Local Files with Google 17 HACK 07: Google Docs on the Run 19 HACK 08: Back Up All Your Google Docs Files 21 HACK 09: Beyond Google: Create Documents with Zoho, EditGrid, and more 23 CHAPTER 2: THE GOOGLE DOCS FAMILY: GOOGLE DOCUMENTS 28 HACK 10: Let Others Subscribe to Your Document Changes 28 HACK U: Blog with Google Docs 31 HACKI2: Insert Special Characters Into Your Documents 34 HACK 13: Search and ReplaceText Using Regulär Expressions 35 HACK 14: "Google Docs Light" for Web Research: Google Notebook 39 HACKI5: Convert a Word File Intoa PDF with Google Docs 42 HACK 16: Write a JavaScript Bookmarklet to Transmogrify Your Documents 44 HACK 17: Remove Formatting Before PastingText Into a Document 47 HACK 18: Prettify Your Document with Inline Styles 47 v CHAPTER 3: THE GOOGLE DOCS FAMILY: GOOGLE SPREADSHEETS 52 HACK 19: Add -

Web 2.0 Tutorials

Web 2.0 Tutorials This list, created by members of the RUSA MARS User Access to Services Committee, is a representative list of tutorials for some of the Web 2.0 products more commonly used in libraries. Link to delicious list (Username UASC, Password Martian1): http://delicious.com/UASC. Blogs Blogs in Plain English http://blip.tv/file/512104 The Common Craft Show Blogger Video Tutorials http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ryb4VPSmKuo http://www.blogger.com/tour_start.g blogger.com EduBlogs Video Tutorials http://edublogs.org/videos/ Edublogs.com EduBlogs is a free blog hosting service for teaching and learning‐related blogs. Blogs come with 20 MB storage space and are listed in the EduBlogs directory. These tutorials describe how to sign up for the service and create a blog. Wikis Wikis in Plain English http://blip.tv/file/246821 The Common Craft Show Wikipedia Tutorial http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Wikipedia_tutorial Wikipedia.com RSS Syndication (e.g. blog or wiki content) W3 Schools RSS Tutorial http://www.w3schools.com/rss/default.asp W3 Schools Describes how to add code to a web site to syndicate its content through RSS (Rich Site Syndication). This site also includes excellent tutorials on XHTML and CSS. What is RSS? http://rss.softwaregarden.com/aboutrss.html Software Garden A basic tutorial introduction to RSS feeds and aggregators for non‐technical people. 1 Feedburner Tutorials http://www.feedburner.com/fb/a/feed101;jsessionid=01563D5FFE69D3CD555134F7280 feedburner.com Mashups Google Mashups Using Flickr and Google Earth http://library.csun.edu/seals/SEALGISBrownGoogleMashups.pdf Mitchell C. Brown, University of California Irvine Mashup Tutorials http://www.deitel.com/ResourceCenters/Web20/Mashups/MashupTutorials/tabid/985/Default.aspx Deitel & Associates VoIP/IM Services Skype Tutorials http://www.tutorpipe.com/free_cat.php?fl=1# Tutorialpipe.com Site contains numerous free tutorials on Skype, Dreamweaver and Google Apps. -

Getting SAP to Talk to Google Gadgets

Getting SAP to talk to Google Gadgets Applies to: SAP ECC6. For more information, visit the ABAP homepage. Summary Using Google Gadgets as a lightweight desktop analytics feature. Author: Patrick Dean Company: Hafele Created on: 27 April 2011 Author Bio Patrick Dean is an ABAPer with 9 years experience, currently working for Hafele. His favorite SDN contributors are Thomas Jung and Jocelyn Dart, enjoys all things Tech and will carry on doing SAP as long as he can get away with it! SAP COMMUNITY NETWORK SDN - sdn.sap.com | BPX - bpx.sap.com | BOC - boc.sap.com | UAC - uac.sap.com © 2011 SAP AG 1 Getting SAP to talk to Google Gadgets Table of Contents Gadgets – Concepts Explained .......................................................................................................................... 3 Presenting the Data from SAP............................................................................................................................ 4 Creating a BSP ............................................................................................................................................... 4 Adding ABAP to your BSP ........................................................................................................................................... 8 Testing the BSP ........................................................................................................................................................... 9 Well Formed XML ..................................................................................................................................................... -

Google Search & Personalized News

Google Search & Personalized News Chris Fitzgerald Walsh Ambassador of Digital Learning, WestEd [email protected] > Get “Even More” Out of Google > 5 Things You Need to Do Right Now 1) Google Advanced Search - www.google.com (Advanced Search) Quickly narrow your results by the order of words, file type, domain, etc. 2) Google “Special” Web Searches - www.google.com/help/features.html Ex. “Population of China”, “weather 92262”, “3(12*7)/6”, “movie: san diego”, “define: love”, “beatles”, “Bill Clinton age” 3) Google Simple Messaging System (SMS) - www.google.com/sms Ex. Send a text message to “466453“ with a simple text search like “starbucks 94598”, “oakland ca to san jose ca” 4) Google News – news.google.com Customize your own newspaper from sources all over the world. Create RSS news feeds based on keywords. 5) Google Alerts - www.google.com/alerts Have Google find the news and information you want and deliver it to you via email. > 5 Things to Play with Soon 1) Google Search Preferences - www.google.com (Preferences) Set the language, number of results, and safe search levels for your individual computer. 2) iGoogle - www.google.com/ig Add content and rearrange it anywhere on your personal start page. Add Google Gadgets in a click. 3) Google Desktop & Gadgets - desktop.google.com Index the files and your personal web history on your computer. Add Gadgets to your desktop. 4) Google Language Tools - www.google.com (Language Tools) Search pages in a specific language. Instantly translate pages on the Web. 5) Google Custom Search Engines – www.google.com/coop/cse Create your own safe, personalized search engine. -

Google Code Google Code Offers Quick Access to Google Apis and Open Source Code for Develope Rs.Current Offerings Include Google

Google Code Google code offers quick access to Google APIs and open source code for develope rs.Current offerings include Google Maps API, Google Webmaster Tools, Google Web Toolkit, Google AJAX Search API, Google Gadgets, Google Desktop SDK, Google KML , Google Toolbar API, AdWords API, Google Data APIs, Google Checkout API, and Go ogle Talk XMPP. Google also provides a Google Code FAQ. Visit Google Code Google Co-op Google Co-op is a platform that let you customize Web searches for Google users and users on your own Web site. You can create a custom engine, where you specif y the Web site URLs to be included in the search, and also use this to place a p erson Web site search box on your own Web site. Visit Google Co-op Google Labs Nicknamed "Google's Technology Playground," Google Labs provides access to some of Google's beta and in-development projects. You can try the prototypes and the n send your comments on the product or service directly to Google developers. So me of the current prototypes available include Google Extensions for Firefox, Go ogle Related Links, Google page Creator, Google Scholar, Web Alerts and more. Visit Google Labs Sponsored Information & Analytics: The Secret Weapon of Top-Performing Companies.: Hear h ow companies like yours are applying analytics to drive profitable growth, cost takeout and efficiency savings. [Click for larger screenshot] Google Personalized If you have a Google account, visit Google.com while signed in and you can perso nalize your Google Web page with news headlines, games, stock quotes, different Web site search boxes, a Gmail preview window and more. -

A Semantic Approach for Web Widget Mashup

A SEMANTIC APPROACH FOR WEB WIDGET MASHUP Jinan Fiaidhi, Adam McLellan and Sabah Mohammed Department of Computer Science, Lakehead University 955 Oliver Road, Thunder Bay, Ontario P7B 5E1, Canada Keywords: Gadgets, Mashup, Semantic web, Widgets. Abstract: The current status of the most popular web widget formats was examined with regard to composition of existing widgets into more complex mashups. A prototype was created demonstrating the creation of a mashup in web widget format using other web widgets as components. A search tool was developed which crawls and indexes in semantic format the metadata of web widgets found in a public repository. This tool provides a web widget interface to find other web widgets, and serves as the first pre-requisite tool for further work in this area. A likely path towards further results in this area is discussed. 1 INTRODUCTION and developers, the development methodology has had little time to mature as yet. Web Widgets/gadgets are serving an important role There remains a great deal of duplicated effort in in the modern web. For example, content producers web widget development, with tens of thousands of seek to syndicate their content in order to reach a widgets available which independently implement broader audience, as well as attracting visitors to common functionality. New tools which could their main sites. Portal providers seek to provide a provide a more modular approach to web widget variety of interesting content to make their website a development would be invaluable, both in reducing valuable destination for their visitors. These goals costs of new development, and in speeding new can be achieved through the use of web widgets. -

* His Is the Original Ubuntuguide. You Are Free to Copy This Guide but Not to Sell It Or Any Derivative of It. Copyright Of

* his is the original Ubuntuguide. You are free to copy this guide but not to sell it or any derivative of it. Copyright of the names Ubuntuguide and Ubuntu Guide reside solely with this site. This guide is neither sold nor distributed in any other medium. Beware of copies that are for sale or are similarly named; they are neither endorsed nor sanctioned by this guide. Ubuntuguide is not associated with Canonical Ltd nor with any commercial enterprise. * Ubuntu allows a user to accomplish tasks from either a menu-driven Graphical User Interface (GUI) or from a text-based command-line interface (CLI). In Ubuntu, the command-line-interface terminal is called Terminal, which is started: Applications -> Accessories -> Terminal. Text inside the grey dotted box like this should be put into the command-line Terminal. * Many changes to the operating system can only be done by a User with Administrative privileges. 'sudo' elevates a User's privileges to the Administrator level temporarily (i.e. when installing programs or making changes to the system). Example: sudo bash * 'gksudo' should be used instead of 'sudo' when opening a Graphical Application through the "Run Command" dialog box. Example: gksudo gedit /etc/apt/sources.list * "man" command can be used to find help manual for a command. For example, "man sudo" will display the manual page for the "sudo" command: man sudo * While "apt-get" and "aptitude" are fast ways of installing programs/packages, you can also use the Synaptic Package Manager, a GUI method for installing programs/packages. Most (but not all) programs/packages available with apt-get install will also be available from the Synaptic Package Manager. -

A Web-Based, Offline-Able, and Personalized Runtime Environment

Computer Standards & Interfaces 34 (2012) 212–224 Contents lists available at SciVerse ScienceDirect Computer Standards & Interfaces journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/csi A Web-based, Offline-able, and Personalized Runtime Environment for executing applications on mobile devices Yung-Wei Kao a,⁎, ChiaFeng Lin a, Kuei-An Yang a, Shyan-Ming Yuan a,b a Department of Computer Science, National Chiao Tung University, 1001 Ta Hsueh Rd., Hsinchu 300, Taiwan b College of Computing & Informatics, Providence University, 200 Chung Chi Rd., Taichung 43301, Taiwan article info abstract Article history: An increasing number of people use cell phones daily. Users are not only capable of making phone calls, but Received 18 April 2011 can also install applications on their mobile phones. When creating mobile applications, developers usually Received in revised form 20 June 2011 encounter the cross-platform incompatibility problem (for example, iPhone applications cannot be executed Accepted 23 August 2011 on the Android platform). Moreover, because mobile Web browsers have increasingly supported more and Available online 8 September 2011 more Web-related standards, Web applications are more possible to be executed on different platforms than mobile applications. However, the problem of Web application is that it cannot be executed in offline Keywords: Mobile device mode. This study proposes a Web-based platform for executing applications on mobile devices. This platform Offline mobile Web application provides several services for developers such as offline service, content adaptation service, and synchroniza- Mobile content adaptation tion service. With the help of the proposed platform, application developers can develop and publish offline Web applications easily with simplified external Web content and synchronization capability.