Arguing the Case for Welsh Crime Fiction

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

English Extension I

ENGLISH EXTENSION I Crime Genre Essay: “Genre sets a framework of conventions. How useful is it to understand texts in terms of genre? Are texts more engaging when they conform to the conventions, or when they challenge and play with conventions?” “Genres offer an important way of framing texts which assists comprehension. Genre knowledge orientates competent readers of the genre towards appropriate attitudes, assumptions and expectations about a text which are useful in making sense of it. Indeed, one way of defining genre is as a ‘set of expectations.’” (Neale, 1980) The crime fiction genre, which began during the Victorian Era, has adapted over time to fit societal expectations, changing as manner of engaging an audience. Victorian text The Manor House Mystery by J.S. Fletcher may be classified as an archetypal crime fiction text, conforming to conventions whilst The Skull beneath the Skin by P.D. James, The Real Inspector Hound by Tom Stoppard and Capote directed by Bennet Miller challenge and subvert conventions. The altering of conventions is an engaging element of modern crime fiction, and has somewhat, become a convention itself. Genre, Roland Barthes argues, is “a set of constitutive conventions and codes, altering from age to age, but shared by a kind of implicit contract between writer and reader” thus meaning it is “ultimately an abstract conception rather than something that exists empirically in the world.”(Jane Feuer, 1992) The classification of literary works is shaped – and shapes – culture, attitude and societal influence. The crime fiction genre evolved following the Industrial Revolution when anxiety grew within the expanding cities about the frequency of criminal activity. -

Week 4 Independent Study Packet

5th Week 4 Grade Independent Study Packet Education.com 5 MORE Days of Independent Activities in Reading, Writing, Math, Science, and Social Studies ANSWERINCLUDED KEYS Find worksheets, games, lessons & more at education.com/resources © 2007 - 2020 Education.com Helpful Hints for Students and Families Materials You Will Need: Pencils Extra paper or a notebook/journal (You may put everything into one notebook if you like.) Colored pencils, markers, or crayons for some of the activities Copy paper or poster paper Internet access for online research Extra supplies for the Science and optional Design activities Directions & Tips There is a schedule for each day. Read the directions carefully before completing each activity. Check off each of the activities when you finish them on the menu. Make sure to plan your time so that you don’t let things pile up at the end. Make sure an adult signs the activity menu before you bring it back to school. You may complete these activities in any order. Find worksheets, games, lessons & more at education.com/resources 2 © 2007 - 2020 Education.com Find worksheets, games, lessons & more at education.com/resources © 2007 - 2020 Education.com Activity Menu Day 1 Day 2 Day 3 Day 4 Day 5 Reading Read for 20 minutes and complete the daily reading activity. Write a Letter Act Out a Make a Make a Make a to the Author Commercial Mind Map Movie Trailer Found Poem What is What is What is What is What is a Science Fiction? Fantasy? Mystery? a Biography? Memoir? Writing My “Best Self” Feelings Perseverance Seeing Things Perseverance Timeline Word Search Journal from Another in Challenging Angle Times Grammar Grammar: Suffix Clues Common Circle the Prefix Practice Suffixes Suffixes Prefixes! Pond and Their ?; ! Meanings Math Census Data : Census Data : Census Data : Ninja Word Hunt Secret Working for Working for Working for Code Math a Living 1 a Living 2 a Living 3 Alphabetize the United States Learn About Social U.S. -

Sunday Morning Grid 4/1/18 Latimes.Com/Tv Times

SUNDAY MORNING GRID 4/1/18 LATIMES.COM/TV TIMES 7 am 7:30 8 am 8:30 9 am 9:30 10 am 10:30 11 am 11:30 12 pm 12:30 2 CBS CBS News Sunday Face the Nation (N) Paid Program JB Show History Astro. Basketball 4 NBC Today in L.A. Weekend Meet the Press (N) (TVG) Hockey Boston Bruins at Philadelphia Flyers. (N) PGA Golf 5 CW KTLA 5 Morning News at 7 (N) Å KTLA News at 9 KTLA 5 News at 10am In Touch Paid Program 7 ABC News This Week News News News Paid NBA Basketball 9 KCAL KCAL 9 News Sunday (N) Joel Osteen Schuller Mike Webb Paid Program REAL-Diego Paid 11 FOX In Touch Paid Fox News Sunday News Paid Program I Love Lucy I Love Lucy 13 MyNet Paid Matter Fred Jordan Paid Program 18 KSCI Paid Program Paid Program 22 KWHY Paid Program Paid Program 24 KVCR Paint With Painting Joy of Paint Wyland’s Paint This Oil Painting Kitchen Mexican Martha Jazzy Real Food Chefs Life 28 KCET 1001 Nights 1001 Nights Mixed Nutz Edisons Biz Kid$ Biz Kid$ Things That Aren’t Here Anymore More Things Aren’t Here Anymore 30 ION Jeremiah Youseff In Touch Paid NCIS: Los Angeles Å NCIS: Los Angeles Å NCIS: Los Angeles Å NCIS: Los Angeles Å 34 KMEX Misa de Pascua: Papa Francisco desde el Vaticano Fútbol Fútbol Mexicano Primera División (N) República Deportiva 40 KTBN James Win Walk Prince Carpenter Jesse In Touch PowerPoint It Is Written Jeffress K. -

Peter Scott: Publications

Peter Scott: Publications 1. Books Peter Scott, Strategies for Postsecondary Education, London: Croom Helm,1975 Peter Scott, The Crisis of the University, London: Croom Helm, 1984 Peter Scott, Knowledge and Nation, Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 1990 Michael Gibbons, Camille Limoges, Helga Nowotny, Simon Schwartzman, Peter Scott and Martin Trow, The New Production of Knowledge: The Dynamics of Science and Research in Contemporary Societies, London: Sage 1994 [Japanese translation, Maruzen, Tokyo 1997; Spanish translation, Ediciones Pomares-Corredor, Barcelona 1997] Peter Scott, The Meanings of Mass Higher Education, Buckingham: Open University Press,1995 Catherine Bargh, Peter Scott and David Smith, Governing Universities: Changing the Culture? Buckingham: Open University Press, 1996 Peter Scott (ed.), The Globalization of Higher Education, Buckingham: Open University Press, 1998 [Chinese translation, McGraw-Hill Education (Asia) / Peking University Press, 2012) Peter Scott (ed.) Higher Education Re-formed, London: Falmer Press, 2000 Catherine Bargh, Jean Bocock, Peter Scott and David Smith University Leadership: The Role of the Chief Executive, Buckingham: Open University Press, 2000 Helga Nowotny, Peter Scott and Michael Gibbons Re-Thinking Science: Knowledge and the Public in an Age of Uncertainity, Cambridge: Polity Press, 2001 [Repenser la Science; savoir et société à l’ère de l’incertitude, Paris: Éditions Belin, 2003; Wissenschaft neu denken: Wissen und Öffentlichkeit in eineam Zeitalter Ungewißheit, Velbrück Wissenschaft 2004; Chinese translation, Shanghai Jiao Tong University Press, 2012] Lars Engwall and Peter Scott (eds.) Trust in Universities, Wenner-Gren Volume 86, London: Portland Press, 2013 Claire Callender and Peter Scott (eds.) Browne and Beyond: Modernizing English Higher Education, London: Institute of Education Press (Bedford Way Papers), 2013 1 2. -

February 4, 2020 (XL:2) Lloyd Bacon: 42ND STREET (1933, 89M) the Version of This Goldenrod Handout Sent out in Our Monday Mailing, and the One Online, Has Hot Links

February 4, 2020 (XL:2) Lloyd Bacon: 42ND STREET (1933, 89m) The version of this Goldenrod Handout sent out in our Monday mailing, and the one online, has hot links. Spelling and Style—use of italics, quotation marks or nothing at all for titles, e.g.—follows the form of the sources. DIRECTOR Lloyd Bacon WRITING Rian James and James Seymour wrote the screenplay with contributions from Whitney Bolton, based on a novel by Bradford Ropes. PRODUCER Darryl F. Zanuck CINEMATOGRAPHY Sol Polito EDITING Thomas Pratt and Frank Ware DANCE ENSEMBLE DESIGN Busby Berkeley The film was nominated for Best Picture and Best Sound at the 1934 Academy Awards. In 1998, the National Film Preservation Board entered the film into the National Film Registry. CAST Warner Baxter...Julian Marsh Bebe Daniels...Dorothy Brock George Brent...Pat Denning Knuckles (1927), She Couldn't Say No (1930), A Notorious Ruby Keeler...Peggy Sawyer Affair (1930), Moby Dick (1930), Gold Dust Gertie (1931), Guy Kibbee...Abner Dillon Manhattan Parade (1931), Fireman, Save My Child Una Merkel...Lorraine Fleming (1932), 42nd Street (1933), Mary Stevens, M.D. (1933), Ginger Rogers...Ann Lowell Footlight Parade (1933), Devil Dogs of the Air (1935), Ned Sparks...Thomas Barry Gold Diggers of 1937 (1936), San Quentin (1937), Dick Powell...Billy Lawler Espionage Agent (1939), Knute Rockne All American Allen Jenkins...Mac Elroy (1940), Action, the North Atlantic (1943), The Sullivans Edward J. Nugent...Terry (1944), You Were Meant for Me (1948), Give My Regards Robert McWade...Jones to Broadway (1948), It Happens Every Spring (1949), The George E. -

Dylan Thomas CD Booklet

THE ESSENTIAL DYLAN THOMAS Includes Under Milk Wood – Richard Burton and cast Return Journey to Swansea – Dylan Thomas and cast MODERN ∼ CLASSICS Poetry and Stories Read by Richard Bebb • Jason Hughes • Philip Madoc • Michael Sheen NA434312D Preface The voice of Dylan Thomas, on paper or on advance and 10 per cent royalty deal a recording, is unmistakable. His rich play of thereafter, to fix a date to record. He failed language and images informed all his work to show on the scheduled day, but did and it was reflected in his distinctive manner make the next date (22 February 1952) at of performance which, like his life, was the Steinway Hall in New York. The large and vivid. All this rightly made him a recording engineer was Peter Bartók, son of personality as well as a poet – certainly, he the composer Béla Bartók. Thomas recorded left an unforgettable impression on all those poems and, when he realised there was he met. It was one reason why, in the latter space left on the LPs, added Memories of part of his career, he was so popular on the Christmas. American lecture and poetry circuit. This, of course, is a marvel for history He was, perhaps, the first outstanding but presents a particular challenge for poet-performer of the recording era. Many subsequent performers of his work. of his recordings remain, from those he Performance, like fashion, is shot through made for the BBC and also for the far- with the style of the period, and Thomas’s sighted Caedmon label in the US. -

PHILOSOPHIES of CRIME FICTION by JOSEF HOFFMANN Translated by Carolyn Kelly, Nadia Majid & Johanna Da Rocha Abreu NEW TITLE

PHILOSOPHIES OF CRIME FICTION BY JOSEF HOFFMANN Translated By Carolyn Kelly, Nadia Majid & Johanna da Rocha Abreu NEW TITLE MARKETING: A groundbreaking book from an internationally respected writer/academic th Pub. date: 25 July 2013 who has a deep and unique expertise on crime fiction Price: £16.99 Hoffmann references a who’s who of top crime writers – Conan Doyle, ISBN13: 978-1-84344-139-7 Chesterton, Hammett, Camus, Borges, Christie, Chandler, Lewis Binding: Paperback Provides an utterly fresh understanding of the philosophical ideas which Format: Royal(234 x 156mm) underpin crime fiction Extent: 192pp Shows how the insights supplied by great crime writers enable key Rights: World philosophical ideas to be appreciated by a wide audience Market Confirms how much more accessible are crime writers than their philosophical None Restrictions: counterparts – and successful at putting across tenets of philosophy Philosophy / Literary Market: A book for students of philosophy of all ages – and for all crime fiction Theory / Crime Fiction devotees BIC code: HPX / DSA /FF MARKET: Rpt. Code: NP Popular philosophy, Literary Theory, Crime Fiction DESCRIPTION: 'More wisdom is contained in the best crime fiction than in conventional philosophical essays' - Wittgenstein For a review copy, to arrange an author Philosophies of Crime Fiction provides a considered analysis of the philosophical ideas interview or for further information, to be found in crime literature - both hidden and explicit. Josef Hoffmann ranges please contact: Alexandra Bolton expertly across influences and inspirations in crime writing with a stellar cast including +44 (0) 1582 766 348 Conan Doyle, G K Chesterton, Dashiell Hammett, Albert Camus, Borges, Agatha +44 (0) 7824 646 881 Christie, Raymond Chandler and Ted Lewis. -

Parody, Popular Culture, and the Narrative of Javier Tomeo

PARODY, POPULAR CULTURE, AND THE NARRATIVE OF JAVIER TOMEO by MARK W. PLEISS B.A., Simpson College, 2007 M.A., University of Colorado at Boulder, 2009 A thesis submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of the University of Colorado in partial fulfillment of the requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Spanish and Portuguese 2015 This thesis entitled: Parody, Popular Culture, and the Narrative of Javier Tomeo written by Mark W. Pleiss has been approved for the Department of Spanish and Portuguese __________________________________________________ Dr. Nina L. Molinaro __________________________________________________ Dr. Juan Herrero-Senés __________________________________________________ Dr. Tania Martuscelli __________________________________________________ Dr. Andrés Prieto __________________________________________________ Dr. Robert Buffington Date __________________________________ The final copy of this thesis has been examined by the signatories, and We find that both the content and the form meet acceptable presentation standards of scholarly work in the abovementioned discipline. iii Pleiss, Mark W. (Ph.D. Spanish Literature, Department of Spanish and Portuguese) Parody, Popular Culture, and the Narrative of Javier Tomeo Dissertation Director: Professor Nina L. Molinaro My thesis sketches a constellation of parodic Works Within the contemporary Spanish author Javier Tomeo's (1932-2013) immense literary universe. These novels include El discutido testamento de Gastón de Puyparlier (1990), Preparativos de viaje (1996), La noche del lobo (2006), Constructores de monstruos (2013), El cazador de leones (1987), and Los amantes de silicona (2008). It is my contention that the Aragonese author repeatedly incorporates and reconfigures the conventions of genres and sub-genres of popular literature and film in order to critique the proliferation of mass culture in Spain during his career as a writer. -

Download (7Mb)

A Thesis Submitted for the Degree of PhD at the University of Warwick Permanent WRAP URL: http://wrap.warwick.ac.uk/110901 Copyright and reuse: This thesis is made available online and is protected by original copyright. Please scroll down to view the document itself. Please refer to the repository record for this item for information to help you to cite it. Our policy information is available from the repository home page. For more information, please contact the WRAP Team at: [email protected] warwick.ac.uk/lib-publications THE BRITISH LIBRARY BRITISH THESIS SERVICE COPYRIGHT Reproduction of this thesis, other than as permitted under the United Kingdom Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988, or under specific agreement with the copyright holder, is prohibited. This copy has been supplied on the understanding that it is copyright material and that no quotation from the thesis may be published without proper acknowledgement. REPRODUCTION QUALITY NOTICE The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the original thesis. Whilst every effort has been made to ensure the highest quality of reproduction, some pages which contain small or poor printing may not reproduce well. Previously copyrighted material (journal articles, published texts etc.) is not reproduced. THIS THESIS HAS BEEN REPRODUCED EXACTLY AS RECEIVED Between Identity and Practice: The Narratives of the Intellectual in the Twentieth-Century by Stephen Palmer BA, MSc A Thesis submitted for the degree of PhD in the University of Warwick. Institute of Education -

Samson Agonistes Performed by Iain Glen and Cast 1 Introduction - on a Festival Day 8:55 2 Chorus 1: This, This Is He

POETRY UNABRIDGED John Milton Samson Agonistes Performed by Iain Glen and cast 1 Introduction - On a Festival Day 8:55 2 Chorus 1: This, this is he... 3:19 3 Samson: I hear the sound of words... 2:16 4 Chorus 1: Tax not divine disposal, wisest Men... 1:45 5 Samson: That fault I take not on me... 2:03 6 Chorus 1: Thy words to my remembrance bring... 2:33 7 Manoa: Brethren and men of Dan, for such ye seem... 3:11 8 Samson: Appoint not heavenly disposition, Father... 2:56 9 Manoa: I cannot praise thy Marriage choices, Son... 3:36 10 Manoa: With cause this hope relieves thee... 4:22 11 Chorus 1: Desire of wine and all delicious drink... 4:05 12 Samson: O that torment should not be confin’d... 2:45 13 Chorus 3: Many are the sayings of the wise... 3:07 14 Chorus 3: But who is this, what thing of Sea or Land? 1:14 15 Dalila: With doubtful feet and wavering resolution... 2:05 16 Dalila: Yet hear me Samson; not that I endeavour... 6:47 17 Samson: I thought where all thy circling wiles would end... 7:32 2 18 Chorus 1: She’s gone, a manifest Serpent by her sting... 3:24 19 Samson: Fair days have oft contracted wind and rain. 0:48 20 Harapha: I come not Samson, to condole thy chance... 7:15 21 Samson: Among the Daughters of the Philistines... 3:15 22 Chorus 1: His Giantship is gone somewhat crestfall’n.. -

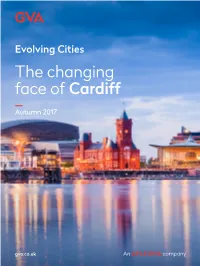

The Changing Face of Cardiff

Evolving Cities The changing face of Cardiff Autumn 2017 gva.co.uk Evolving cities The UK’s cities are The Changing Face of Cardiff is one of our series of reports looking at how undergoing a renaissance. the UK’s key cities are evolving and Large scale place making the transformational change that is schemes are dramatically occurring, either in terms of the scale improving how they are of regeneration activity or a shift in perception. perceived, making them more desirable places to For each city, we identify the key locations where such change has live and work, and better occurred over the last 10 years, able to attract new people and the major developments that and businesses. continue to deliver it. We then explore the key large scale regeneration opportunities going forward. Cardiff today Cardiff is the capital Cardiff’s city status and wealth The city has become a popular The city’s transport links are international location for businesses was primarily accrued from its tourist location which has been undergoing significant improvement. is supported by the city’s ability to and focal point of Wales. coal exporting industry, which led underpinned by major investments At Cardiff Central Station, Network Rail offer high quality office stock within Historically the city to the opening of the West Bute in leisure, sports and cultural venues. has recently added a new platform, Central Square, Callaghan Square flourished, becoming Dock and transformed Cardiff’s The construction of Mermaid Quay facilities and a modern entrance to and Capital Quarter. Key occupiers the world’s biggest coal landscape. -

The City of Cardiff Council, County Borough Councils of Bridgend, Caerphilly, Merthyr Tydfil, Rhondda Cynon Taf and the Vale of Glamorgan

THE CITY OF CARDIFF COUNCIL, COUNTY BOROUGH COUNCILS OF BRIDGEND, CAERPHILLY, MERTHYR TYDFIL, RHONDDA CYNON TAF AND THE VALE OF GLAMORGAN AGENDA ITEM NO: 7 THE GLAMORGAN ARCHIVES JOINT COMMITTEE 27 June 2014 REPORT FOR THE PERIOD 1 March – 31 May 2014 REPORT OF: THE GLAMORGAN ARCHIVIST 1. PURPOSE OF REPORT This report describes the work of Glamorgan Archives for the period 1 March to 31 May 2014. 2. BACKGROUND As part of the agreed reporting process the Glamorgan Archivist updates the Joint Committee quarterly on the work and achievements of the service. 3. Members are asked to note the content of this report. 4. ISSUES A. MANAGEMENT OF RESOURCES 1. Staff: establishment Maintain appropriate levels of staff There has been no staff movement during the quarter. From April the Deputy Glamorgan Archivist reduced her hours to 30 a week. Review establishment The manager-led regrading process has been followed for four staff positions in which responsibilities have increased since the original evaluation was completed. The posts are Administrative Officer, Senior Records Officer, Records Assistant and Preservation Assistant. All were in detriment following the single status assessment and comprise 7 members of staff. Applications have been submitted and results are awaited. 1 Develop skill sharing programme During the quarter 44 volunteers and work experience placements have contributed 1917 hours to the work of the Office. Of these 19 came from Cardiff, nine each from the Vale of Glamorgan and Bridgend, four from Rhondda Cynon Taf and three from outside our area: from Newport, Haverfordwest and Catalonia. In addition nine tours have been provided to prospective volunteers and two references were supplied to former volunteers.