Restoring the 'Mam'

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cardiff Registration Enquiry

Review of Polling Districts and Polling Places 2019 Summary of Recommendations to Polling Districts & Polling Places ADAMSDOWN Polling Polling Polling Community Electorate Venue Returning Officer’s Comments District Place Station Rating AA AA Tredegarville Primary School, Glossop Rd, Adamsdown Adamsdown 1,281 Good No change AB AB Family Contact Children and Family Centre, Metal St, Adamsdown Adamsdown 1,394 Good No change AC AC Stacey Primary School, Stacey Road Adamsdown 874 Good No change AD AD The Rubicon, Nora Street, Adamsdown Adamsdown 980 Good No change AE AD The Rubicon, Nora Street, Adamsdown Adamsdown 451 Good No change BUTETOWN Polling Polling Polling Community Electorate Venue Returning Officer’s Comments District Place Station Rating NA NA Butetown Community Centre, Loudon Square, Butetown Butetown 2,699 Good No change NB NB Portacabin in County Hall, Car Park Bay 1, Atlantic Wharf Butetown 2,010 Satisfactory No change NC NC Mountstuart Primary School (The Nursery), Stuart St Entrance Butetown 2,252 Good No change 1 of 15 Review of Polling Districts and Polling Places 2019 CAERAU Polling Polling Polling Community Electorate Venue Returning Officer’s Comments District Place Station Rating TA TA Portacabin, Between 18-28, The Sanctuary, Caerau Caerau 684 Satisfactory No change Caerau 1,591 Good TB TB Immanuel Presbyterian Church, Heol Trelai, Caerau No change Caerau 862 Good TC TC Ysgol Gymraeg Nant Caerau, Caerau Lane/Heol y Gaer, Caerau No change TD TD Western Leisure Centre, (The Community Room), Caerau Lane Caerau 444 Good -

Cardiff Bay 1 Cardiff Bay

Cardiff Bay 1 Cardiff Bay Cardiff Bay Welsh: Bae Caerdydd The Bay or Tiger Bay Cardiff Bay Cardiff Bay shown within Wales Country Wales Sovereign state United Kingdom Post town CARDIFF Postcode district CF10 Dialling code 029 EU Parliament Wales Welsh Assembly Cardiff South & Penarth Website http:/ / www. cardiffharbour. com/ Cardiff Harbour Authority List of places: UK • Wales • Cardiff Bay (Welsh: Bae Caerdydd) is the area created by the Cardiff Barrage in South Cardiff, the capital of Wales. The regeneration of Cardiff Bay is now widely regarded as one of the most successful regeneration projects in the United Kingdom.[1] The Bay is supplied by two rivers (Taff and Ely) to form a 500-acre (2.0 km2) freshwater lake round the former dockland area south of the city centre. The Bay was formerly tidal, with access to the sea limited to a couple of hours each side of high water but now provides 24 hour access through three locks[2] . History Cardiff Bay played a major part in Cardiff’s development by being the means of exporting coal from the South Wales Valleys to the rest of the world, helping to power the industrial age. The coal mining industry helped fund the building of Cardiff into the Capital city of Wales and helped the Third Marquis of Bute, who owned the docks, become the richest man in the world at the time. As Cardiff exports grew, so did its population; dockworkers and sailors from across the world settled in neighbourhoods close to the docks, known as Tiger Bay, and communities from up to 45 different nationalities, including Norwegian, Somali, Yemeni, Spanish, Italian, Caribbean and Irish helped create the unique multicultural character of the area. -

The Changing Face of Cardiff

Evolving Cities The changing face of Cardiff Autumn 2017 gva.co.uk Evolving cities The UK’s cities are The Changing Face of Cardiff is one of our series of reports looking at how undergoing a renaissance. the UK’s key cities are evolving and Large scale place making the transformational change that is schemes are dramatically occurring, either in terms of the scale improving how they are of regeneration activity or a shift in perception. perceived, making them more desirable places to For each city, we identify the key locations where such change has live and work, and better occurred over the last 10 years, able to attract new people and the major developments that and businesses. continue to deliver it. We then explore the key large scale regeneration opportunities going forward. Cardiff today Cardiff is the capital Cardiff’s city status and wealth The city has become a popular The city’s transport links are international location for businesses was primarily accrued from its tourist location which has been undergoing significant improvement. is supported by the city’s ability to and focal point of Wales. coal exporting industry, which led underpinned by major investments At Cardiff Central Station, Network Rail offer high quality office stock within Historically the city to the opening of the West Bute in leisure, sports and cultural venues. has recently added a new platform, Central Square, Callaghan Square flourished, becoming Dock and transformed Cardiff’s The construction of Mermaid Quay facilities and a modern entrance to and Capital Quarter. Key occupiers the world’s biggest coal landscape. -

The City of Cardiff Council, County Borough Councils of Bridgend, Caerphilly, Merthyr Tydfil, Rhondda Cynon Taf and the Vale of Glamorgan

THE CITY OF CARDIFF COUNCIL, COUNTY BOROUGH COUNCILS OF BRIDGEND, CAERPHILLY, MERTHYR TYDFIL, RHONDDA CYNON TAF AND THE VALE OF GLAMORGAN AGENDA ITEM NO: 7 THE GLAMORGAN ARCHIVES JOINT COMMITTEE 27 June 2014 REPORT FOR THE PERIOD 1 March – 31 May 2014 REPORT OF: THE GLAMORGAN ARCHIVIST 1. PURPOSE OF REPORT This report describes the work of Glamorgan Archives for the period 1 March to 31 May 2014. 2. BACKGROUND As part of the agreed reporting process the Glamorgan Archivist updates the Joint Committee quarterly on the work and achievements of the service. 3. Members are asked to note the content of this report. 4. ISSUES A. MANAGEMENT OF RESOURCES 1. Staff: establishment Maintain appropriate levels of staff There has been no staff movement during the quarter. From April the Deputy Glamorgan Archivist reduced her hours to 30 a week. Review establishment The manager-led regrading process has been followed for four staff positions in which responsibilities have increased since the original evaluation was completed. The posts are Administrative Officer, Senior Records Officer, Records Assistant and Preservation Assistant. All were in detriment following the single status assessment and comprise 7 members of staff. Applications have been submitted and results are awaited. 1 Develop skill sharing programme During the quarter 44 volunteers and work experience placements have contributed 1917 hours to the work of the Office. Of these 19 came from Cardiff, nine each from the Vale of Glamorgan and Bridgend, four from Rhondda Cynon Taf and three from outside our area: from Newport, Haverfordwest and Catalonia. In addition nine tours have been provided to prospective volunteers and two references were supplied to former volunteers. -

Review of 20,000 Saints

Review of Twenty thousand saints , a novel by Fflur Dafydd Talybont (Ceredigion), Alcemi, 2008, pp 251 Why should an award-winning young Welsh writer turn to English for her third novel? To reach a wider audience, according to conventional wisdom. But for Fflur Dafydd, who won the prose medal at the 2006 Eisteddfod with her Welsh language novel Atyniad, the answer is not that simple. It is about finding her voice: 'Writing in Welsh is completely different to writing in English; because fewer writers are writing in Welsh, there is so much more to be done, and there is real opportunity to be innovative with the way that you use the language. English is different; less vulnerable as a language and therefore more robust and exacting, so that when writing in English I’m less concerned with language innovation and more concerned with finding my own voice and identity within that language.' The novel, 'Twenty Thousand Saints', (Alcemi, 2008) is set on the tiny island of Bardsey, off the north east coast of Wales. Today Bardsey is known (if at all) as a bird watching paradise, but in the 6th century it was an established centre of pilgrimage on a par with Lindisfarne and Iona; three visits to Bardsey were worth a pilgrimage to Rome. There are Arthurian associations, too, as there are almost everywhere in Wales: Merlin is alleged to be buried here (along with twenty thousand Celtic saints, hence the title of the novel), and one theory at least identifies Bardsey as the Isle of Avalon, the last resting place of Arthur and Guinevere. -

Jane Hutt: Businesses That Have Received Welsh Government Grants During 2011/12

Jane Hutt: Businesses that have received Welsh Government grants during 2011/12 1 STOP FINANCIAL SERVICES 100 PERCENT EFFECTIVE TRAINING 1MTB1 1ST CHOICE TRANSPORT LTD 2 WOODS 30 MINUTE WORKOUT LTD 3D HAIR AND BEAUTY LTD 4A GREENHOUSE COM LTD 4MAT TRAINING 4WARD DEVELOPMENT LTD 5 STAR AUTOS 5C SERVICES LTD 75 POINT 3 LTD A AND R ELECTRICAL WALES LTD A JEFFERY BUILDING CONTRACTOR A & B AIR SYSTEMS LTD A & N MEDIA FINANCE SERVICES LTD A A ELECTRICAL A A INTERNATIONAL LTD A AND E G JONES A AND E THERAPY A AND G SERVICES A AND P VEHICLE SERVICES A AND S MOTOR REPAIRS A AND T JONES A B CARDINAL PACKAGING LTD A BRADLEY & SONS A CUSHLEY HEATING SERVICES A CUT ABOVE A FOULKES & PARTNERS A GIDDINGS A H PLANT HIRE LTD A HARRIES BUILDING SERVICES LTD A HIER PLUMBING AND HEATING A I SUMNER A J ACCESS PLATFORMS LTD A J RENTALS LIMITED A J WALTERS AVIATION LTD A M EVANS A M GWYNNE A MCLAY AND COMPANY LIMITED A P HUGHES LANDSCAPING A P PATEL A PARRY CONSTRUCTION CO LTD A PLUS TRAINING & BUSINES SERVICES A R ELECTRICAL TRAINING CENTRE A R GIBSON PAINTING AND DEC SERVS A R T RHYMNEY LTD A S DISTRIBUTION SERVICES LTD A THOMAS A W JONES BUILDING CONTRACTORS A W RENEWABLES LTD A WILLIAMS A1 CARE SERVICES A1 CEILINGS A1 SAFE & SECURE A19 SKILLS A40 GARAGE A4E LTD AA & MG WOZENCRAFT AAA TRAINING CO LTD AABSOLUTELY LUSH HAIR STUDIO AB INTERNET LTD ABB LTD ABER GLAZIERS LTD ABERAVON ICC ABERDARE FORD ABERGAVENNY FINE FOODS LTD ABINGDON FLOORING LTD ABLE LIFTING GEAR SWANSEA LTD ABLE OFFICE FURNITURE LTD ABLEWORLD UK LTD ABM CATERING FOR LEISURE LTD ABOUT TRAINING -

Schooner Way Cardiff

Archaeology Wales 6FKRRQHU:D\ &DUGLII 'HVN%DVHG$VVHVVPHQW %\ ,UHQH*DUFLD5RYLUD%$0$3K' 5HSRUW1R Archaeology Wales Limited, Rhos Helyg, Cwm Belan, Llanidloes, Powys SY18 6QF Tel: +44 (0) 1686 440371 E-mail: [email protected] Archaeology Wales 6FKRRQHU:D\ &DUGLII 'HVN%DVHG$VVHVVPHQW 3UHSDUHG)RU$VEUL3ODQQLQJ/WG (GLWHGE\5RZHQD+DUW $XWKRULVHGE\5RZHQD+DUW 6LJQHG 6LJQHG 3RVLWLRQ3URMHFW0DQDJHU 3RVLWLRQ3URMHFW0DQDJHU 'DWH 'DWH %\ ,UHQH*DUFLD5RYLUD%$0$3K' 5HSRUW1R 1RYHPEHU Archaeology Wales Limited, Rhos Helyg, Cwm Belan, Llanidloes, Powys SY18 6QF Tel: +44 (0) 1686 440371 E-mail: [email protected] CONTENTS Summary 1 1. Introduction 2 2. Site Description 2 3. Methodology 3 4. Archaeological and Historical Background 4 4.1 Previous Archaeological Studies 4 4.2 The Historic Landscape 5 4.3 Scheduled Ancient Monuments 5 4.4 Listed Buildings 5 4.5 Non designated sites 8 4.6 Historical background 10 5. Map Regression 15 6. Aerial Photographs 16 7. New Sites 18 8. Site Visit 18 9. Assessing visual impact 18 10.Impact Assessment 19 10.1 Assessment of archaeological potential and importance 19 10.2 Potential impacts from proposed development 19 10.3 Mitigation 19 11.Conclusion 20 12.Sources Appendix I: Gazetteer of sites recorded on the regional HER Appendix II: List of sites recorded on the NMR Appendix III: Specification List of Figures Figure 1 Site of proposed development Figure 2 Listed buildings within 1km radius from the site Figure 3 Detail of listed buildings N of the site Figure 4 Detail of listed buildings S of the site Figure 5 Sites recorded on the regional HER Figure 6 &RXQW\6HULHVILUVWHGLWLRQVKRZLQJDSSUR[LPDWHORFDWLRQWRVLWH Figure 7 &RXQW\6HULHVVHFRQGHGLWLRQVKRZLQJDSSUR[LPDWHORFDWLRQWR VLWH i Plates Plate 1 Centre of the site. -

U:\Reports\Deldecided Lst by Ward.Rpt

Page: 1 Applications decided by Delegated powers between 01/03/2007and 31/03/2007 Ward: ADAMSDOWN AppNum Registered AppName Proposal Location Dcn DcnDate 06/02796/C 11/01/2007 Roger North Long & CHANGE OF USE FROM RETAIL - OFFICES TO 133-134, Clifton Street, Adamsdown, PER 08/03/2007 Partners RETAIL 4 NO. 1 BED APARTMENTS AND 1 NO. Cardiff DETACHED 2 BED HOUSE 06/02797/C 13/12/2006 Mr. B. Singh EXISTING USE AS 4 FLATS 26 Piercefield Place, Adamsdown, PER 23/03/2007 Cardiff 07/00006/C 03/01/2007 Mr Brown CONVERSION OF EXISTING COACH 2A Blanche Street, Adamsdown, Cardiff PER 26/03/2007 HOUSE/WORKSHOP TO DWELLING 07/00026/C 05/01/2007 Mr J Sheriff CONVERSION TO 2 NO. SELF CONTAINED 8 Emerald Street, Adamsdown, Cardiff PER 02/03/2007 FLATS 07/00132/C 22/01/2007 Cardiff County Council ALTERATION TO AN EXISTING WINDOW TO Stacey Road Primary School, Stacey PER 12/03/2007 FORM A NEW DOORWAY WITH STEPS AND Road, Adamsdown, Cardiff RAILINGS TO PROVIDE DIRECT ACCESS FROM THE RECEPTION CLASSROOM TO THE SECURE GARDEN AREA 07/00156/C 25/01/2007 Mr Ashtari CONVERSION TO 2 FLATS WITH ALTERATIONS 17 Ruby Street, Adamsdown, Cardiff PER 21/03/2007 TO FORM REAR FRENCH DOORS 07/00224/C 02/02/2007 Mr & Mrs C Williams DETACHED DOMESTIC GARAGE 70 Stacey Road, Adamsdown, Cardiff PER 13/03/2007 07/00225/C 08/02/2007 Mr Ghaffer GROUND AND FIRST REAR EXTENSIONS AND 15 Piercefield Place, Adamsdown, PER 26/03/2007 CONVERSION TO 5 FLATS Cardiff Ward: BUTETOWN 06/02795/C 22/12/2006 Tragus Holdings Ltd. -

The Party's Over?

The Party’s Over? 63rd Annual International Conference 25 - 27 March 2013 City Hall, Cardiff, Wales Cover images: courtesy of www.visitcardiff.com Stay informed of Routledge Politics journal news and book highlights Explore Routledge Politics journals with your 14 days’ free access voucher, available at the Routledge stand throughout the conference. Sign up at the To discover future news and offers, Routledge stand and make sure you subscribe to the Politics we’ll enter you into our & International Relations Bulletin. exclusive prize draw to win a Kindle! explore.tandfonline.com/pair BIG_4664_PSA_A4 advert_final.indd 1 27/02/2013 11:38 Croeso i Gaerdydd! Welcome to Cardiff! Dear Conference delegate, I’d like to welcome you to this 63rd Conference of the Political Studies Association, held in Cardiff for the first time and hosted by the University of Cardiff. We are expecting over 600 delegates, representing over 80 different countries, to join us at Cardiff’s historic City Hall. The conference theme is ‘The Party’s Over?’; are the assumptions that have underpinned political life and political analysis sustainable? This subject will most certainly be explored during our Plenary Session ‘Leveson and the Future of Political Journalism’, a debate that has enormous ramifications for the future of UK politics. We will bring together some of the most passionate and eloquent voices on this topic; Chris Bryant MP, Trevor Kavanagh, Mick Hume and Professor Brian Cathcart. This year’s Government and Opposition- sponsored Leonard Schapiro lecture will be given by Professor Donatella Della Porta, who will consider the issue of political violence, the new editor of the American Political Science Review, Professor John Ishiyama, will discuss ‘The Future of Political Science’ and the First Minister of Wales, Carwyn Jones AM, will address attendees at the conference dinner. -

Geographies of Diversity in Cardiff

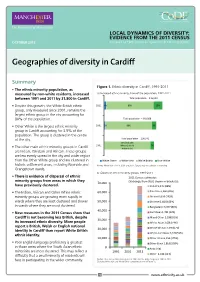

LOCAL DYNAMICS OF DIVERSITY: EVIDENCE FROM THE 2011 CENSUS OCTOBER 2013 Prepared by ESRC Centre on Dynamics of Ethnicity (CoDE) Geographies of diversity in Cardiff Summary Figure 1. Ethnic diversity in Cardiff, 1991-2011 • The ethnic minority population, as measured by non-white residents, increased a) Increased ethnic minority share of the population, 1991-2011 between 1991 and 2011 by 31,800 in Cardiff. Total population – 346,090 • Despite this growth, the White British ethnic 2011 4% 80% 15% group, only measured since 2001, remains the largest ethnic group in the city accounting for 80% of the population. Total population – 310,088 • Other White is the largest ethnic minority 2001 2% 88% 9% group in Cardiff accounting for 3.5% of the population. The group is clustered in the centre of the city. Total population – 296,941 93% (includes 1991 White Other & 7% • The other main ethnic minority groups in Cardiff White Irish) are Indian, Pakistani and African. These groups are less evenly spread in the city and wider region than the Other White group and are clustered in White Other White Irish White British Non-White historic settlement areas, including Riverside and Notes: White Irish <1% in 2001 and 2011. Figures may not add due to rounding. Grangetown wards. b) Growth of ethnic minority groups, 1991-2011 • There is evidence of dispersal of ethnic 2011 Census estimates minority groups from areas in which they 70,000 (% change from 2001 shown in brackets): have previously clustered. Indian 9,435 (88%) • The Indian, African and Other White ethnic 60,000 Pakistani 6,960 (40%) minority groups are growing more rapidly in African 6,639 (162%) wards where they are least clustered and slower 50,000 Chinese 6,182 (105%) in wards where they are most clustered. -

CARDIFF Open Storage AVAILABLE PORT LAND to LET Mains Power and 0.24 Hectares (0.6 Acres) Water Connected Compass Road, Cardiff Docks, CF10 4LB WC Facilities

Secure Yard / CARDIFF Open Storage AVAILABLE PORT LAND TO LET Mains Power and 0.24 Hectares (0.6 acres) Water Connected Compass Road, Cardiff Docks, CF10 4LB WC Facilities Available Property Delivering Property Solutions Compass Road, Cardiff Docks, Cardiff, Available Property Description Sat Nav: CF10 4LB M4 A470 M4 The site totals approximately 0.6 acres of secure, level, gravel surfaced land. A48(M) It benefits from direct access via Roath Dock Road or Rover Way and is within the secure Tongwynlais Llanishen A48 confines of the Port of Cardiff, 1 mile to the south of Cardiff City Centre. A470 The Port provides multimodal facilities, including quayside access capable of M4 M4 accommodating vessels of 35,000 dwt and a newly constructed rail loading facility to J32 10.8 km facilitate rail handling services. ABP has invested significantly in the port over the past few A48 years, modernising infrastructure and supply customers with specialist storage solutions A470 M4 St Fagans and handling equipment. Existing occupiers on the Port include Travis Perkins, Valero, A4232 A48 J29 15.6 km Cemex, Tarmac, EMR and Bob Martin. Cardiff Leckwith Atlantic M4 Wharf Location Specification A4232 J33 17.2 km Compass Road is strategically situated within + Industrial / open storage the heart of Cardiff Docks in Cardiff Bay, + 24-hour port security - access via Roath Dock Road Approximately 1 mile south of Cardiff City or Rover Way Centre. The site offers the opportunity for ALL MAPS ARE INDICATIVE ONLY occupiers to benefit from access to Junction 29 + WC facilities and 30 to the East and Junction 33 to the West + Mains services consisting of electricity and water via the newly extended A4232 (Eastern Bay Service Charge Potential Uses Link) dual carriageway as well as easy access + Excellent road access to Junctions 29, 30 & 33 A provision will be included for any lease Industrial to the centre of Cardiff, Wales’ capital city. -

Museum of London Docklands-October 2019

Grumpy Old Men’s Club update The October outing for the Grumpies on Wednesday 30th was an interesting visit to the Museum of London Docklands. The museum, which is situated in Limehouse and is close to Canary Wharf, tells the history of London's River Thames and the growth of Docklands. From Roman settlement to Docklands’ regeneration, the museum unlocks the history of London’s river, port and people in this historic warehouse. It displays a wealth of objects from whale bones to WWII gas masks in state-of-the-art galleries, including Sailortown, an atmospheric re-creation of 19th century riverside Wapping; and London, Sugar & Slavery, which reveals the city’s involvement in the transatlantic slave trade. Trade expansion from 1600 to 1800 tells the story of how ships sailed from London to India and China and brought back cargoes of spices, tea and silk. The museum’s building is central to this story. It was built at the time of the transatlantic slave trade, to store the sugar from the West Indian plantations where enslaved men, women and children worked. The trade in enslaved Africans and sugar was nicknamed the Triangular Trade. Slave ships travelled across the Atlantic in a triangle between Britain, west Africa, and sugar plantations in the Americas. Vast fortunes were made from this triangle. By the mid-18th century there were so many ships in the port of London that their cargoes often rotted before they could be unloaded. The West India Docks were built to prevent this long wait for space at the quayside.