The Role of the Private Secretary by Edward Bowles, a Sometime Private Secretary

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Erosion of Parliamentary Government

The Erosion of Parliamentary Government JOHN MAJOR CENTRE FOR POLICY STUDIES 57 Tufton Street London SW1P 3QL 2003 THE AUTHOR THE RT HON JOHN MAJOR CH was Prime Minister of Great Britain and Northern Ireland from 1990 to 1997, having previously served as Foreign Secretary and Chancellor of the Exchequer. He was a Conservative Member of Parliament for Huntingdon from 1979 to 2001. Since leaving politics, he has returned to business in the private sector. He also lectures around the world and is active in many charities. The aim of the Centre for Policy Studies is to develop and promote policies that provide freedom and encouragement for individuals to pursue the aspirations they have for themselves and their families, within the security and obligations of a stable and law-abiding nation. The views expressed in our publications are, however, the sole responsibility of the authors. Contributions are chosen for their value in informing public debate and should not be taken as representing a corporate view of the CPS or of its Directors. The CPS values its independence and does not carry on activities with the intention of affecting public support for any registered political party or for candidates at election, or to influence voters in a referendum. ISBN No. 1 903219 62 0 Centre for Policy Studies, October 2003 Printed by The Chameleon Press, 5 – 25 Burr Road, London SW18 CONTENTS Prologue 1. The Decline of Democracy 1 2. The Decline of Parliament 3 3. The Politicisation of the Civil Service 9 4. The Manipulation of Government Information 12 5. -

Assistant Private Secretary Job Description A

B2 - Assistant Private Secretary Job description A critical role, responsible for the operation and smooth running of the private office for Civil Service Group (CSG). The Group supports both the senior leadership of the Civil Service and the Permanent Secretary of the Cabinet Office. It is a dynamic environment where collaboration across departmental boundaries is critical to success. Information about the Cabinet Office can be found at: www.cabinet-office.gov.uk This is an exciting and challenging role for a highly motivated and enthusiastic individual with organisational, service delivery, interpersonal and communications skills. You will need to be able to work effectively at speed and under pressure. You will need to be able to manage multiple priorities, write clearly and succinctly, and liaise effectively with a variety of stakeholders. You will support the Director General (Tracey Waltho) and Director (Andrea Ledward) and work as part of a small private office team - consisting of a newly created Chief of Staff, and diary manager to ensure the smooth operation of the Civil Service Group. The successful candidate will ensure the strategic coordination of CSG’s forward look, quickly grasping and prioritising work. They will support the wider Senior Leadership Team - and their weekly meetings and strategic planning. You will have the ability to set up and implement new systems in a constantly changing environment. There will be an opportunity to develop and pick up other pieces of policy work and you will deputise for the Chief of Staff as necessary. A high degree of commitment, flexibility and energy is required for this challenging and important role. -

Principal Private Secretary Office of the Secretary of State for Wales

Principal Private Secretary Office of the Secretary of State for Wales SCS Pay Band 1 Closing Date: 23:55 Sunday 12th July 2020 Move your mouse pointer over the buttons Contents below and click for more information This is an interactive document and is best viewed using Adobe Acrobat Reader. Click here to download. Introduction Why join the Office of the Secretary of State for Wales? This is a fantastic There can hardly have been a more exciting or OSSW, No10, other Government Departments, the challenging time to be in the Office of the Secretary Welsh Government and a range of private and public opportunity to take on an of State for Wales (OSSW). The Government’s Union sector stakeholders. You will need to have strong exciting role at the heart agenda, particularly in the wake of Covid-19, is one of political nous, an in-depth knowledge of Whitehall and the key priorities for the Prime Minister. Sitting at the an ability to work exceptionally well under pressure. of the Department heart of Government, the Office has a key role to play in The Principal Private Secretary works closely with me in delivering that agenda. leading the department, ensuring a smooth relationship We are a very small department, with around 50 staff between ministers and officials, and communicating and offices in Cardiff and London. We take a close Ministers’ objectives to the wider department. As a interest in any issues that have potential implications visible leader, you will be able to motivate your team for Wales. We collaborate with other Government to create a high performing, confident culture. -

(Rppm 04) Staffing in the Prime Minister's Office

Written evidence submitted by the Cabinet Office (RPPM 04) STAFFING IN THE PRIME MINISTER'S OFFICE Thank you for your letter of 27 March, requesting information about staffing in the Prime Minister's Office. Details on the Senior Civil Servants and Special Advisers working for the Prime Minister are below. Civil Servants Political staff Director General, No10, and Principal Chief of Staff to the Prime Minister Private Secretary to the Prime Minister • Ed Llewellyn • Chris Martin Private Office Deputy Chiefs of Staff to the Prime • Simon Case, Deputy Principal Private Minister Secretary • Kate Fall • Nigel Casey, Private Secretary for • Oliver Dowden Foreign Affairs* • Gus Jaspert, Private Secretary for Private Office supporting staff Home Affairs* • Kate Shouesmith • Kate Joseph, Private Secretary for • Isabel Spearman Foreign Affairs and Development* • Frances Trivett • Tim Kiddell, Private Secretary, Speechwriter, and Civil Society (in Policy Unit the Policy Unit)* • Jo Johnson MP, Head of the Policy • Ed Whiting, Private Secretary for Unit** Public Services* • Christopher Lockwood, Deputy Head • Dan York-Smith, Private Secretary for of the Policy Unit Economic Affairs* • Andrew Dunlop, Scotland • Daniel Korski, Enterprise and Policy Unit Entrepreneurship • Emily Ackroyd, Welfare, Employment • Kate Marley, Policy Unit and Pensions* • Alex Morton, Housing, Communities • Conrad Bailey, Defence* and Local Government • Tim Luke, Business, Innovation and • Richard Parr, International Trade* Development • Antonia Williams, Deputy Director, -

Cabinet Office Structure Charts Contents

Structure Charts To contents page Cabinet Office Structure Charts contents • Cabinet Office organisation chart • Grades and pay scales (London) (National) (June 2010) • Cabinet Office Ministers • Prime Minister’s Office • Deputy Prime Minister’s Office and Constitution Group • Private Office Group (and Cabinet Secretary’s Office) • Office of the Parliamentary Counsel • Honours and Appointments • Economics and Domestic Affairs Secretariat • Strategy Unit • European and Global Issues Secretariat • National Security Secretariat • Joint Intelligence Organisation • Efficiency and Reform • Corporate Services Group Non Ministerial Departments reporting to the Minister for the Cabinet Office • The Central Office of Information • The National School of Government Cabinet Office Ministers Cabinet Secretary Sir Gus O’Donnell Support to the Prime Minister’s Political & Office Cabinet, the Efficiency & National Security Constitutional Prime Minister & Reform Reform the Deputy PM Deputy Prime Minister’s Office • Efficiency and Reform European & Global National Security Strategy Issues Secretariat • Office of Government Cabinet Secretary’s Secretariat Office Commerce • Government Communications • Civil Service Capability Economic & Propriety & Ethics Joint Intelligence Domestic Affairs • Chief Information Private Office Organisation Secretariat Officer & SIRO • Office for Civil Society Office of the • Major Projects Parliamentary • Commodity Counsel Procurement Strategy Unit • Commercial Portfolio • Operational Excellence Honours and • Governance Reform -

('Ht � � OFFICE Memorandulva

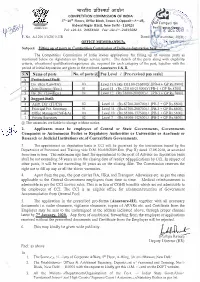

·fi1-< dl ll fa� tq \:IT al Illl � I �r-· COMPETITION COMMISSION OF INDIA ;::;�,;;-, th .3th -10 Floors, Office Block, Tower-1,Opposit� M•:111s, '�"l_,-�>\\ «'�:a ----·--·t · 1 Kidwai Nagar (East), New Delhi - 110023 h' Co::: p e 1 e iti�: ., 1 0 r ,, t "''°' ,,.._.,\\ ·, � -t/)C>U Tel: +91-11- 24664100 Fax: +91-1. .- 20815022 i u c t'019 _ � � 1 . No.A-12011/1/2019-HR Dated: � ?�el:1���,.�9f9�c // ('Ht � � OFFICE MEMORANDUlVa. - .. �, t;_J�o 1 sp[, � .. // G Subject: Filling up of posts in Competition Commission oflndia on deputation bas1 . �.. ,-.,'.-v , .,,.•• _· . _.,. ... __ ,__ ·,.�,,.., The Competition Commission of India invites applications for filling up of various posts as mentioned below on dep.utation on foreign service terms. The details of the posts along with eligibility criteria, educational qualification/experience etc. required for each category of the post, together with the period of initial deputation are given in the enclosed Annexures I & II. S.N Name of posts No. of posts@ Pay Level / (Pre-revised pay scale) A Professional Staff: + Dir. (Eco./Law/F A) 03 Level 13A (Rs.131100-216600)/ [PB-4 GP Rs.8900] ,...I + 2 Joint Director (Eco.) 01 Level 13 (Rs.123100-215900)/ r PB-4 GP Rs.8700] + / 3 Dy. Dir. (Law/Eco.) 04 Level 12 (Rs.78800-209200) I [PB-3 GP Rs.7600] B Su(!port Staff: + 4 Asstt. Dir. (IT/CS) 03 Level 11 (Rs.67700-208700) I [PB-3 GP Rs.6600] + 5 Principal Pvt. Secretary 01 Level 11 (Rs.67700-208700) I rPB-3 GP Rs.66001 + 6 Office Manager(CS/F&A) 04 Level 10 (Rs.56100-177500) I [PB-3 GP Rs.5400] + 7 Private Secretary 02 Level 7 (Rs.44900-142400) I [PB-2 GP Rs.46001 @ The vacancies are liable to change without notice. -

Particulars of Its Organisation, Functions and Duties

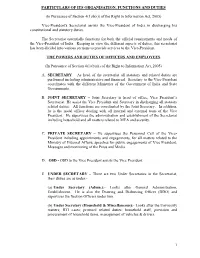

PARTICULARS OF ITS ORGANISATION, FUNCTIONS AND DUTIES (In Pursuance of Section 4(1)(b)(i) of the Right to Information Act, 2005) Vice-President's Secretariat assists the Vice-President of India in discharging his constitutional and statutory duties. The Secretariat essentially functions for both the official requirements and needs of the Vice-President of India. Keeping in view the different aspects of duties, this secretariat has been divided into various sections to provide services to the Vice-President. THE POWERS AND DUTIES OF OFFICERS AND EMPLOYEES (In Pursuance of Section 4(1)(b)(ii) of the Right to Information Act, 2005) A. SECRETARY – As head of the secretariat all statutory and related duties are performed including administrative and financial. Secretary to the Vice-President coordinates with the different Ministries of the Government of India and State Governments. B. JOINT SECRETARY – Joint Secretary is head of office, Vice President’s Secretariat. He assist the Vice President and Secretary in discharging all statuary related duties. All functions are coordinated by the Joint Secretary. In addition, he is the nodal officer dealing with all internal and external tours of the Vice President. He supervises the administration and establishment of the Secretariat including household and all matters related to MEA and security. C. PRIVATE SECRETARY – He supervises the Personnel Cell of the Vice- President including appointments and engagements, for all matters related to the Ministry of External Affairs, speeches for public engagements of Vice President, Messages and monitoring of the Press and Media. D. OSD - OSD to the Vice President assists the Vice President. -

Study Report on Parliamentary Secretary

STUDY REPORT ON PARLIAMENTARY SECRETARY MINISTRY OF PARLIAMENTARY AFFAIRS 1997 INDEX S. No. Chapter Page 1. I- Introduction and 2 Methodology 2. II- Rules and Regulations on the Institution of Parliamentary 3 Secretary 3. III- Institution of Parliamentary Secretary 4-8 In U.K., Canada, Germany and France 4. IV- Institution of Parliamentary 9-11 Secretary in India 5. V- Conclusion 12 6. VI- Gains/Benefits 13 ANNEXURES I 14 II 15 III 16-18 IV 19 V 20 VI 21-22 VII 23 VIII 24 IX 25-33 X 34-35 XI 36-37 1 CHAPTER-I INTRODUCTION AND METHODOLOGY 1.1. INTRODUCTION : It has long been felt that a study may be undertaken on the Institution of the Parliamentary Secretary. The purpose of the study is to consolidate all the relevant and useable information on the Institution of Parliamentary Secretary in a scientific manner. 1.2. METHODOLOGY : The following relevant files relating to Parliamentary Secretaries have been gone through to have an in depth knowledge about the Institution of Parliamentary Secretary in India as well as in U.K.:- (i) F.4(25)/84-WS (ii) F.4(5)/85-WS (III) F.4(21)/88-WS (IV) F.4(22)/90-WS The Ministry of Home Affairs and Cabinet Secretariat, wherever felt necessary were also consulted. 2 CHAPTER-II RULES AND REGULATIONS REGARDING PARLIAMENTARY SECRETARIES 2.1 The Parliamentary Secretary is not a member of the Council of Ministers as the term „Minister‟ appearing in Articles 75 of the Constitution does not include Parliamentary Secretary and is not appointed by the President. -

Ministerial Code

MINISTERIAL CODE CABINET OFFICE August 2019 MINISTERIAL CODE Foreword by The Prime Minister The mission of this Government is to deliver Brexit on 31st October for the purpose of uniting and re-energising our whole United Kingdom and making this country the greatest place on earth. We will seize the opportunities offered by Brexit, investing in education, technology and infrastructure, unlocking the talents of the whole nation and levelling up across our United Kingdom so that no town or community is ever again left behind or forgotten. In doing so, we will make our country the greatest place to invest or set up a business, the greatest place to send your kids to school and the greatest place in the world to live and bring up a family. To fulfil this mission, and win back the trust of the British people, we must uphold the very highest standards of propriety – and this code sets out how we must do so. There must be no bullying and no harassment; no leaking; no breach of collective responsibility. No misuse of taxpayer money and no actual or perceived conflicts of interest. The precious principles of public life enshrined in this document – integrity, objectivity, accountability, transparency, honesty and leadership in the public interest – must be honoured at all times; as must the political impartiality of our much admired civil service. Crucially, there must be no delay - and no misuse of process or procedure by any individual Minister that would seek to stall the collective decisions necessary to deliver Brexit and secure the wider changes needed across our United Kingdom. -

Stuart Government, 1660-1714

Gale Primary Sources Start at the source. Stuart Government, 1660-1714 Dr Alan Marshall Bath Spa University Various source media, State Papers Online EMPOWER™ RESEARCH Paper empires such documents for the reign of Charles II, while many ancillary documents for this reign are located in SP 30. It is clear that all post-Renaissance states were drawn The other material in the state papers is made up of to the concept of statecraft. At least in its English working drafts of letters, or treaties, acts of parliament, context, this statecraft drew its evidence from the personal journals, memoranda, depositions, or lists An notion of the record and examples from the past; ideas, example of such normal documentation, for early May that were inherent in the notion of the common law 1665, can be found at SP29/121. As such, these with its steady accretion of documentary precedent, documents occasionally represent something of a one- which became central to English consciousness and sided conversation for the historian and need to be therefore to English men of government. These ideas tracked though into other collections. Nevertheless all were also at work in both domestic and diplomatic aspects of central, and some local, government activity discourses. They were a vital auxiliary to the are covered to a certain degree and the documents, development of the office of secretary of state and to wisely used, can allow us to get behind the scenes of the idea of 'public records', both of which had some of the Stuart regime's narrative (its public policy-making), their origins in medieval administration, but were to see it at its daily work and meet the people involved transformed in the early modern English state. -

Dof Pre Release Access List

DoF STATISTICAL RELEASES TO WHICH PRE-RELEASE ACCESS IS GRANTED AND PERSONS WITH PRE- RELEASE ACCESS. Updated 31 March 2021 Statistical Release Pre-release recipients Cost to Businesses of Completing Statistical • Minister of Finance DoF Surveys issued by Northern Ireland • Special Advisor DoF Departments • Permanent Secretary DoF • Principal Information Officer DoF • Deputy Departmental Private Secretary, Minister’s Private Office DoF Burden to Households and Individuals of • Minister of Finance DoF Completing Statistical Surveys issued by • Special Advisor DoF Northern Ireland Departments • Permanent Secretary DoF • Principal Information Officer DoF • Deputy Departmental Private Secretary, Minister’s Private Office DoF NISRA Customer Satisfaction Survey • Minister of Finance DoF • Special Advisor DoF • Permanent Secretary DoF • Departmental Private Secretary, Minister’s Private Office DoF • Principal Information Officer DoF Census of Population 2011 • Minister for Finance DoF • Permanent Secretary DoF • Special Adviser DoF • Departmental Private Secretary, DoF Minister’s Private Office • Principal Information Officer DOF Weekly Deaths • Minister of Health DoH (at 8.30am) • Permanent Secretary DoH (at 8.30am) • Deputy Principal Information Officer DoH (8.30am) 08/05/2020 • Minister of Health DoH (at 9.10am)* • Permanent Secretary DoH (at 9.10am)* • Deputy Principal Information Officer DoH (at 9am) *Due to an error on the morning of release these recipients did not receive pre-release access 17/04/2020 & 24/04/2020 • Minister of Finance -

Appendix a – Breakdown of Interviews

Appendix A – Breakdown of Interviews The interviews were drawn from four ESRC projects: • The Changing Role of Central Government Departments in Britain ESRC Award No.L124251023 [Research conducted 1995–1998] • Labour and the Reform of Whitehall: Inheritance, Transition and Accommo dation ESRC Award No.R000222657 [Research conducted 1998–2000] • Public Service Delivery Programme: Analysing Delivery Chains in the Home Office. ESRC Award. No.RES.153-25-0037. [Research conducted 2005–7] • Building Bridges between Political Biography and Political Science – A Methodo- logically Innovative Study of the Core Executive Under New Labour ESRC Award No. RES-000-22-2040. [Research conducted 2006–7] Interviews Numbers Senior civil servants 149 Other civil servants 48 Labour ministers 15 Conservative ministers 21 Special advisers 6 NGO representatives 63 204 Appendix B – Permanent Secretaries and Their Relevant Departments 1996–2004 1. Ministry of Agriculture, Fisheries and Food (MAFF) 1996 Permanent R J Packer Secretary 1997 (before the Permanent R J Packer general election) Secretary 1997 (after the Permanent R J Packer general election) Secretary 1998 Permanent R J Packer Secretary 1999 Permanent R J Packer Secretary 2000 Permanent Brian Secretary Bender In 2001, combined with the Department of Environment, Transport and the Regions (DETR) to form the Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs (DEFRA). 2. Cabinet Office 1996 Secretary of the Cabinet and Robin Butler Head of the Home Civil Service Permanent Secretary (Office of R Mountfield