Bertram Mitford and the Bambatha Rebellion]

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

NATAL, TRE ZULU ROYAL FAMILY and the IDEOLOGY of SEGREGATION Shula Marks on the 18Th October 1913 Dinmulu Ka Cetshmo, Son Of

NATAL, TRE ZULU ROYAL FAMILY AND THE IDEOLOGY OF SEGREGATION Shula Marks On the 18th October 1913 Dinmulu ka Cetshmo, son of the last Zulu king, died in exile on a farm in the Middelburg district of the Transvaal. In response to the condolences of the Government conveyed by the local magistrate, Mankulumana, his aged adviser, who had shared Dinmululs trials and had voluntarily shared his exile, remarked with some justification: It is you [meaning the ~overnment] who killed the one we have now buried, you killed his father, and killed him. We did not invade your country, but you invaded ours. I fought for the dead man! S father, we were beaten, you took our King away, but the Queen sent him back to us, and we were happy. The one whom we now mourn did no wrong. There is no bone which will not decay. What we now ask is, as you have killed the father, to take care of the children. (1) For the next twenty years Dinmulufsson a.nd heir, Solomon, engaged in a prolonged struggle, first to be recognized as chief of the Usuthu, as his fatherfs most immediate followers were known, and then to be recognized as the Zulu parmount, by the Natal authorities and the Union government. Despite the fact that he gained considerable support both at the level of central government and from a coalition of interests in Zululand itself, the strong opposition of the Natal administration prevented the realization of his demands; after his death and during the minority of his potential heirs, his brother Mshiyeni, who had worked for some time in Natal, and who was believed to be ltmostanxious to obtain the good opinion of the government and most amenable to the control of the Native Comtni~sioner~~(2), was accorded some wider recognition as Social Head of the Zulu Nation and Regent. -

The Health and Health System of South Africa: Historical Roots of Current Public Health Challenges

Series Health in South Africa 1 The health and health system of South Africa: historical roots of current public health challenges Hoosen Coovadia, Rachel Jewkes, Peter Barron, David Sanders, Diane McIntyre The roots of a dysfunctional health system and the collision of the epidemics of communicable and non-communicable Lancet 2009; 374: 817–34 diseases in South Africa can be found in policies from periods of the country’s history, from colonial subjugation, Published Online apartheid dispossession, to the post-apartheid period. Racial and gender discrimination, the migrant labour system, August 25, 2009 the destruction of family life, vast income inequalities, and extreme violence have all formed part of South Africa’s DOI:10.1016/S0140- 6736(09)60951-X troubled past, and all have inexorably aff ected health and health services. In 1994, when apartheid ended, the health See Editorial page 757 system faced massive challenges, many of which still persist. Macroeconomic policies, fostering growth rather than See Comment pages 759 redistribution, contributed to the persistence of economic disparities between races despite a large expansion in and 760 social grants. The public health system has been transformed into an integrated, comprehensive national service, but See Perspectives page 777 failures in leadership and stewardship and weak management have led to inadequate implementation of what are This is fi rst in a Series of often good policies. Pivotal facets of primary health care are not in place and there is a substantial human resources six papers on health in crisis facing the health sector. The HIV epidemic has contributed to and accelerated these challenges. -

Apartheid & the New South Africa

Apartheid & the New South Africa HIST 4424 MW 9:30 – 10:50 Pafford 206 Instructor: Dr. Molly McCullers TLC 3225 [email protected] Office Hours: MW 1-4 or by appointment Course Objectives: Explore South African history from the beginning of apartheid in 1948, to Democracy in 1994, through the present Examine the factors that caused and sustained a repressive government regime and African experiences of and responses to apartheid Develop an understanding of contemporary South Africa’s challenges such as historical memory, wealth inequalities, HIV/AIDS, and government corruption Required Texts: Books for this class should be available at the bookstore. They are all available online at Amazon, Barnes & Noble, and Half.com. Many are available as ebooks. You can also obtain copies through GIL Express or Interlibrary Loan Nancy Clark & William Worger, South Africa: The Rise and Fall of Apartheid. (New York: Routledge) o Make sure to get the 2011 or 2013 edition. The 2004 edition is too old. o $35.00 new/ $22.00 ebook Clifton Crais & Thomas McLendon: The South Africa Reader: History, Culture, Politics (Duke: 2012) o $22.47 new/ $16.00 ebook Mark Mathabane, Kaffir Boy: An Autobiography – The True Story of a Black Youth’s Coming of Age in Apartheid South Africa (Free Press, 1998) o Any edition is fine o $12.88 new/ $8.99 ebook o On reserve at library & additional copies available Andre Brink, Rumors of Rain: A Novel of Corruption and Redemption (2008) o $16.73 new/ $10.99 ebook Rian Malan, My Traitor’s Heart: A South African Exile Returns to Face his Country, his Tribe, and his Conscience (2000) o $10.32 new/ $9.80 ebook o On reserve at Library Zakes Mda, The Heart of Redness: A Novel (2003) o $13.17 new / $8.99 ebook Jonny Steinberg, Sizwe’s Test: A Young Man’s Journey through Africa’s AIDS Epidemic (2010) o $20.54 new/ $14.24 ebook All additional readings will be available on Course Den Assignments: Reaction Papers – There will be 5 reaction papers to each of the books due over the course of the semester. -

FUGITIVE QUEENS: Amakhosikazi and the Continuous Evolution Of

FUGITIVE QUEENS: Amakhosikazi and the Continuous Evolution of Gender and Power in KwaZulu-Natal (1816-1889) by CAELLAGH D. MORRISSEY A THESIS Presented to the Department of History and International Studies and the Robert D. Clark Honors College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Bachelor of Arts or Science December 2015 An Abstract of the Thesis of Caellagh Morrissey for the degree of Bachelor of Arts in the Department of History and International Studies to be taken December 2015 Title: Fugitive Queens: Amakhosikazi and the Evolution of Gender and Power in KwaZulu-Natal (1816-1889) Professor Lindsay F. Braun Amakhosikazi (elite women) played a vital role within the social, economic, and political reality of the Zulu pre-colonial state. However, histories have largely categorized them as accessory to the lives of powerful men. Through close readings of oral traditions, travelogues, and government documentation, this paper discusses the spaces in which the amakhosikazi exhibited power, and tracks changes in the social position of queen mothers, as well as some members of related groups of elite women, from the early years of the Zulu chiefdom in the 1750s up until the 1887 annexation by Britain and their crucial intervention in royal matters in 1889. The amakhosika=i can be seen operating in a complex social space wherein individual women accessed power through association to political clans, biological and economic reproduction, manipulation, and spiritual influence. Women's access to male power sources changed through both internal political shifts and external pressures. but generally increased in the first half of the 1800s, and the declined over time and with the fracturing of Zulu hegemony. -

GARVEYISM in AFRICA: DR WELLINGTON and THF "AMERICAN MOVEMENT" in TI3[E TRANSKEI, 1925-40 by Bob Edgar During the Peri

GARVEYISM IN AFRICA: DR WELLINGTON AND THF "AMERICAN MOVEMENT" IN TI3[E TRANSKEI, 1925-40 by Bob Edgar During the period surrounding World War I, a wave of millennial fervour swept throw the Ciskei and Transkei of South Africa. A series of millennial movements emerged, one of the most intriguing being led by a Natal-born Zulu, Wellington Butelezi, who began his preaching around 1925. Claiming that he was an American, Butelezi drew direct inspiration from Marcus Gamey, but he infused Gasveyls message with millennial inspiration as he proclaimed a da~of salvation was at hand in which American armies were coming to liberate Africans from European bondage. Over the years, Butelezifs personality has been much maligned and his movement has been considered an ephemeral episode in South African history, but the fact remains that his movement achieved more success than any other Transkeian movement of that period in articulating the grievances and aspirations of Africans. In this paper, I will present a reconstruction of the development of the Butelezi movement and attempt to analyse briefly some of the motivating factors behind it. The details of the early life of llDr Wellington1' are still obscure. Baptised Elias Wellington Butelezi, he was born about 1895 at Ehtonjanene near -- Melmoth, Natal. He received his early education at Mpwnulo, a Lutheran mission school, but after 1918 his parents lost track of him. As his father, Daniel, testified at one of Wellington1 S numerous trials, 'l.. after he returned [from ~pumulo)he wandered about the country .. I did not actually know where he was when he was wandering about the country, and cannot sa~whether he left this country or not .. -

The People of Nkandla in the Zulu Rebellion of 1906

Scientia Militaria, South African Journal of Military Studies, Vol 35, Nr 2, 2007. doi: 10.5787/35-2-39 95 CROSSROADS OF WAR: THE PEOPLE OF NKANDLA IN THE ZULU REBELLION OF 1906 _____________________________________________________________ Prof Paul S. Thompson School of Anthropology, Gender & Historical Studies, University of KwaZulu-Natal … [T]he Commissioner for Native Affairs therefore decided to send … a message so strongly worded as to leave no loophole for Sigananda in case … he was knowingly assisting or harbouring Bambata. The dire result of such action on his part, i.e. ruination by confiscation of property and the practical extermination of the tribe were pointed out and every conceivable pressure, as far as reasoning powers went, were brought to bear on him. (Benjamin Colenbrander, Resident Magistrate, Nkandhla Division, writing in 1906)1 The rebellion and Nkandla The Zulu Rebellion of 1906 was the violent response to the imposition of a poll tax of £1 on all adult males (with exempted categories) by the government of the British South African colony of Natal on the part of a section of the indigenous, Zulu-speaking people. The rebellion was in the nature of “secondary resistance” to European colonization, and the poll tax was only the immediate cause of it. Not all the African people (who made up 82% of the colony’s population) participated in the rebellion; only a few did, but there was the potential for a mass uprising, which inspired great fear among the European settlers (who made up just 8,3% of the population) and prompted the colony’s responsible government to take quick and vigorous action to crush the rebellion before it could spread. -

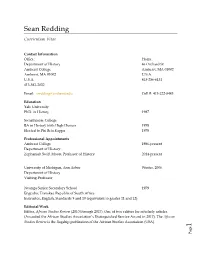

1 Sean Redding

Sean Redding Curriculum Vitae Contact Information Office: Home: Department of History 46 Orchard St. Amherst College Amherst, MA 01002 Amherst, MA 01002 U.S.A. U.S.A. 413-256-6131 413-542-2032 Email: [email protected] Cell #: 413-222-8443 Education Yale University PhD. in History 1987 Swarthmore College BA in History with High Honors 1978 Elected to Phi Beta Kappa 1978 Professional Appointments Amherst College 1986-present Department of History Zephaniah Swift Moore Professor of History 2014-present University of Michigan, Ann Arbor Winter, 2006 Department of History Visiting Professor Nyanga Senior Secondary School 1979 Engcobo, Transkei, Republic of South Africa Instructor, English, Standards 9 and 10 (equivalent to grades 11 and 12). Editorial Work Editor, African Studies Review (2010 through 2017). One of two editors for scholarly articles. (Awarded the African Studies Association’s Distinguished Service Award in 2017). The African Studies Review is the flagship publication of the African Studies Association (USA). 1 Page Peer reviewer for manuscripts for numerous journals, including: African Studies Agricultural History Comparative Studies in Society and History The International Journal of African Historical Studies The Journal of Southern African Studies The Journal of African History Kronos Law and Social Inquiry Meridians Safundi The South African Historical Journal Reviewer for book manuscripts for several publishers, including Blackwell, Palgrave, Oxford University Press, University of Virginia Press, Ohio University Press, and University of Rochester Press. Publications Book SORCERY AND SOVEREIGNTY: TAXATION, POWER AND REBELLION IN SOUTH AFRICA, 1880-1963, Ohio University Press, 2006. Book manuscript in preparation Violence in Rural South Africa, 1902-1965, book length manuscript (in revision). -

A Greater South Africa: White Power in the Region, 1910-1940

CHAPTER 2 A Greater South Africa: White Power in the Region, 1910-1940 A Christian minister called Laputa was going among the tribes from Durban to the Zambezi as a roving evangelist. His word was "Africa for the Africans," and his chief point was that the natives had had a great empire in the past, and might have a great empire again. [While spying on Laputa] it was my business to play the fool.... I explained that I was fresh from England, and believed in equal rights for all men, white and coloured. God forgive me, but I think I said I hoped to see the day when Africa would belong once more to its rightful masters. -JOHN BUCHAN, PresterJohn NINETEEN TEN, the year Prester John was published, was also the year Britain handed over political authority to the nascent Union of South Africa. The novel's hero, David Crawfurd, wins a treasure in gold and diamonds, just as Haggard's hero in King Solomon's Mines did. Even more significantly, Crawfurd prides himself on helping white law and order prevail over the native uprising sparked by Laputa's appeal to the legend ary empire of Prester John. Author John Buchan, who was to become one of the most popular adventure writers of the early twentieth century, had also played a role, as Milner's private secretary, in shaping the framework for the white South African state. And in real life there were those who preached "Africa for the Africans" instead of accepting European rule. Buchan's scenario bore resemblances not only to the Bambatha rebellion in Zululand in 1906 (see chapter 1), but also to the revolt in 1915 led by John Chilembwe in Ny asaland. -

2688 ISS Monograph 127.Indd

SSOUTHOUTH AAFRICANFRICAN GGUERRILLAUERRILLA ARMIESARMIES THE IMPACT OF GUERRILLA ARMIES ON THE CREATION OF SOUTH AFRICA’S ARMED FORCES ROCKY WILLIAMS ISS MONOGRAPH SERIES • No 127, SEPTEMBER 2006 CONTENTS LIST OF ACRONYMS ii FOREWORD iv EXECUTIVE SUMMARY vi CHAPTER 1 1 Introduction CHAPTER 2 5 The political context and the transition to war: Anti-colonial struggles CHAPTER 3 13 The military strategy and doctrine of the Boer Republics and Umkhonto we Sizwe: Two types of people’s war CHAPTER 4 37 The influence of guerrilla armies: The creation of modern national defence forces CHAPTER 5 51 Conclusion ii Rocky Williams iii RENAMO Mozambican National Resistance (Resistência Nacional Moçambicana) SADF South African Defence Force LIST OF ACRONYMS SAIC South African Indian Congress SAP South African Police ANC African National Congress SWAPO South-West Africa People’s Organisation APLA Azanian People’s Liberation Army TBVC Transkei, Bophuthatswana, Venda, Ciskei CBD Civilian-based Defence TDF Transkei Defence Force CPSA Communist Party of South Africa TSA Transvaal Staats Artillerie ESKOM Electricity Supply Commission UDF Union Defence Force FRELIMO Front for the Liberation of Mozambique (Frente de Libertação de Mozambique) UNITA National Union for the Total Independence of Angola (União Nacional para a Independência Total de Angola) JMCC Joint Military Co-ordinating Council ZAPU Zimbabwe African People’s Union MK Umkhonto we Sizwe ZAR Zuid-Afrikaansche Republiek MKIZA MK Intelligence Division ZIPRA Zimbabwe People’s Revolutionary Army MPLA Popular Movement for the Liberation of Angola (Movimento Popular de Libertação de Angola) ZNLA Zimbabwe National Liberation Army NAT ANC Department of National Intelligence and Security NEC National Executive Committee NP National Party NSF Non-Statutory Forces OFS Orange Free State PAC Pan Africanist Congress PMC Political Military Council iv Rocky Williams v The death of Rocky Williams is a great loss to all concerned with security sector transformation in Africa and to all who knew Rocky as a friend. -

History of South Africa

Ministry of Education and Sports HOME-STUDY LEARNING I O R N E S 4 HISTORY OF SOUTH AFRICA August 2020 Published 2020 This material has been developed as a home-study intervention for schools during the lockdown caused by the COVID-19 pandemic to support continuity of learning. Therefore, this material is restricted from being reproduced for any commercial gains. National Curriculum Development Centre P.O. Box 7002, Kampala- Uganda www.ncdc.go.ug SELF-STUDY LEARNING FOREWORD Following the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic, government of Uganda closed all schools and other educational institutions to minimize the spread of the coronavirus. This has affected more than 36,314 primary schools, 3129 secondary schools, 430,778 teachers and 12,777,390 learners. The COVID-19 outbreak and subsequent closure of all has had drastically impacted on learning especially curriculum coverage, loss of interest in education and learner readiness in case schools open. This could result in massive rates of learner dropouts due to unwanted pregnancies and lack of school fees among others. To mitigate the impact of the pandemic on the education system in Uganda, the Ministry of Education and Sports (MoES) constituted a Sector Response Taskforce (SRT) to strengthen the sector’s preparedness and response measures. The SRT and National Curriculum Development Centre developed print home-study materials, radio and television scripts for some selected subjects for all learners from Pre-Primary to Advanced Level. The materials will enhance continued learning and learning for progression during this period of the lockdown, and will still be relevant when schools resume. -

The African Role in the Failure of South African Colonialism, 1902-1910: the Case of Lesotho

Southeastern Regional Seminar in African Studies (SERSAS) The African Role in the Failure of South African Colonialism, 1902-1910: the Case of Lesotho Reuben O. Mekenye Department of History California State University San Marcos, California Tel:(760)750-8032 Fax:(760)750-3430 E-mail: [email protected] Spring 2000 SERSAS Meeting Western Carolina University Cullowhee, NC 14-15 April 2000 No part of this paper should be reproduced or used without the written consent of the author. (Web Editor's Note: to return to the text from the linked endnotes, click on your browser's "Back Icon") Introduction When the Union of South Africa was inaugurated on May 31, 1910, the small kingdom of Basutoland (Lesotho) would have been incorporated into the Union Government. The colonist politicians from the two British colonies of the Cape and Natal and the Boer or Afrikaner republics of the Transvaal and the Orange Free State that constituted the Union, had for long demanded for the annexation of Lesotho to one of the colonies.1 Also included in the colonist demands was the inclusion of Lesotho's fellow British protectorates of Bechuanaland (Botswana) as well as Swaziland within South Africa. However, by Section 151 of the Schedule of South Africa Act (Constitution) of 1909, the incorporation of Lesotho, along with Botswana and Swaziland, was deferred indefinitely.2 Generally, scholars have emphasized the role played by Great Britain, the colonial overlord of Lesotho, as the reason for the postponement of incorporation. They have argued that Britain made a deliberate decision against haste incorporation of Lesotho, together with Botswana and Swaziland, because of its "moral obligation" to the welfare of the people of these three territories or protectorates. -

Introduction to Book 2

The Carrington Extracts From the diaries of ` Caroline Kipling Introduction to Book 2 Book 2 Book 2 of the Extracts continues from the year 1900. Charles Carrington provides an introduction, starting with a brief note on a minor dispute between two Cambridge newspapers in January 1900, and going on to provide a useful summary of the main events of the second South-African War and its aftermath, interleaved with notes on Kipling’s whereabouts at the time. [A.J.W.] CAMBRIDGE CHRONICLE v. CAMBRIDGE INDEPENDENT NEWS 19 JANUARY 1900 A quarrel between two Cambridge local papers. One of them had met Beresford (‘M’Turk’ in Stalky & Co.) and asked him for ‘gen’ about RK’s schooldays. Beresford wrote to RK for permission but got no reply. He then released some stories which did not square with Stalky and Co. The Judge rejected the whole story. Stalky was fiction and it didn’t matter what comment was made on it. ___________________________ BOER WAR DATES [Summary by CEC (Charles Carrington)] 1899-1900 Kruger’s Ultimatum Following an influx of British and other foreign workers to the gold and diamond mines in the two Boer republics, Britain attempted to obtain full voting and citizenship rights for the uitlanders. After negotiations failed, the British tried to force the Boers’ hand, by moving troops up to the borders of the Free State and the Transvaal. On 9 October 1899, President Kruger of the Transvaal issued an ultimatum – ‘Remove your troops or we will declare war on the British Government’. The British didn’t and the Boers did.