Reading 2-1.Indd

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

On the Mechanics of the Bow and Arrow 1

On the Mechanics of the Bow and Arrow 1 B.W. Kooi Groningen, The Netherlands 1983 1B.W. Kooi, On the Mechanics of the Bow and Arrow PhD-thesis, Mathematisch Instituut, Rijksuniversiteit Groningen, The Netherlands (1983), Supported by ”Netherlands organization for the advancement of pure research” (Z.W.O.), project (63-57) 2 Contents 1 Introduction 5 1.1 Prefaceandsummary.............................. 5 1.2 Definitionsandclassifications . .. 7 1.3 Constructionofbowsandarrows . .. 11 1.4 Mathematicalmodelling . 14 1.5 Formermathematicalmodels . 17 1.6 Ourmathematicalmodel. 20 1.7 Unitsofmeasurement.............................. 22 1.8 Varietyinarchery................................ 23 1.9 Qualitycoefficients ............................... 25 1.10 Comparison of different mathematical models . ...... 26 1.11 Comparison of the mechanical performance . ....... 28 2 Static deformation of the bow 33 2.1 Summary .................................... 33 2.2 Introduction................................... 33 2.3 Formulationoftheproblem . 34 2.4 Numerical solution of the equation of equilibrium . ......... 37 2.5 Somenumericalresults . 40 2.6 A model of a bow with 100% shooting efficiency . .. 50 2.7 Acknowledgement................................ 52 3 Mechanics of the bow and arrow 55 3.1 Summary .................................... 55 3.2 Introduction................................... 55 3.3 Equationsofmotion .............................. 57 3.4 Finitedifferenceequations . .. 62 3.5 Somenumericalresults . 68 3.6 On the behaviour of the normal force -

Simply String Art Carol Beard Central Michigan University, [email protected]

International Textile and Apparel Association 2015: Celebrating the Unique (ITAA) Annual Conference Proceedings Nov 11th, 12:00 AM Simply String Art Carol Beard Central Michigan University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/itaa_proceedings Part of the Fashion Design Commons Beard, Carol, "Simply String Art" (2015). International Textile and Apparel Association (ITAA) Annual Conference Proceedings. 74. https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/itaa_proceedings/2015/design/74 This Event is brought to you for free and open access by the Conferences and Symposia at Iowa State University Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in International Textile and Apparel Association (ITAA) Annual Conference Proceedings by an authorized administrator of Iowa State University Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Santa Fe, New Mexico 2015 Proceedings Simply String Art Carol Beard, Central Michigan University, USA Key Words: String art, surface design Purpose: Simply String Art was inspired by an art piece at the Saint Louis Art Museum. I was intrigued by a painting where the artist had created a three dimensional effect with a string art application over highlighted areas of his painting. I wanted to apply this visual element to the surface of fabric used in apparel construction. The purpose of this piece was to explore string art as unique artistic interpretation for a surface design element. I have long been interested in intricate details that draw the eye and take something seemingly simple to the realm of elegance. Process: The design process began with a research of string art and its many interpretations. -

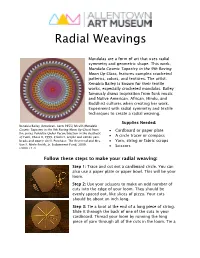

Radial Weavings

Radial Weavings Mandalas are a form of art that uses radial symmetry and geometric shape. This work, Mandala Cosmic Tapestry in the 9th Roving Moon Up-Close, features complex crocheted patterns, colors, and textures. The artist, Xenobia Bailey is known for their textile works, especially crocheted mandalas. Bailey famously draws inspiration from funk music and Native American, African, Hindu, and Buddhist cultures when creating her work. Experiment with radial symmetry and textile techniques to create a radial weaving. Supplies Needed: Xenobia Bailey (American, born 1955) Mv:#9 (Mandala Cosmic Tapestry in the 9th Roving Moon Up-Close) from • Cardboard or paper plate the series Paradise Under Reconstruction in the Aesthetic of Funk, Phase II, 1999, Crochet, acrylic and cotton yarn, • A circle tracer or compass beads and cowrie shell. Purchase: The Reverend and Mrs. • Yarn, string or fabric scraps Van S. Merle-Smith, Jr. Endowment Fund, 2000. • Scissors (2000.17.2) Follow these steps to make your radial weaving: Step 1: Trace and cut out a cardboard circle. You can also use a paper plate or paper bowl. This will be your loom. Step 2: Use your scissors to make an odd number of cuts into the edge of your loom. They should be evenly spaced out, like slices of pizza. Your cuts should be about an inch long. Step 3: Tie a knot at the end of a long piece of string. Slide it through the back of one of the cuts in your cardboard. Thread your loom by running the long piece of yarn through all of the cuts in the loom. -

Bath Time Travellers Weaving

Bath Time Travellers Weaving Did you know? The Romans used wool, linen, cotton and sometimes silk for their clothing. Before the use of spinning wheels, spinning was carried out using a spindle and a whorl. The spindle or rod usually had a bump on which the whorl was fitted. The majority of the whorls were made of stone, lead or recycled pots. A wisp of prepared wool was twisted around the spindle, which was then spun and allowed to drop. The whorl acts to keep the spindle twisting and the weight stretches the fibres. By doing this, the fibres were extended and twisted into yarn. Weaving was probably invented much later than spinning around 6000 BC in West Asia. By Roman times weaving was usually done on upright looms. None of these have survived but fortunately we have pictures drawn at the time to show us what they looked like. A weaver who stood at a vertical loom could weave cloth of a greater width than was possible sitting down. This was important as a full sized toga could measure as much as 4-5 metres in length and 2.5 metres wide! Once the cloth had been produced it was soaked in decayed urine to remove the grease and make it ready for dying. Dyes came from natural materials. Most dyes came from sources near to where the Romans settled. The colours you wore in Roman times told people about you. If you were rich you could get rarer dyes with brighter colours from overseas. Activity 1 – Weave an Owl Hanging Have a close look at the Temple pediment. -

The Musical Kinetic Shape: a Variable Tension String Instrument

The Musical Kinetic Shape: AVariableTensionStringInstrument Ismet Handˇzi´c, Kyle B. Reed University of South Florida, Department of Mechanical Engineering, Tampa, Florida Abstract In this article we present a novel variable tension string instrument which relies on a kinetic shape to actively alter the tension of a fixed length taut string. We derived a mathematical model that relates the two-dimensional kinetic shape equation to the string’s physical and dynamic parameters. With this model we designed and constructed an automated instrument that is able to play frequencies within predicted and recognizable frequencies. This prototype instrument is also able to play programmed melodies. Keywords: musical instrument, variable tension, kinetic shape, string vibration 1. Introduction It is possible to vary the fundamental natural oscillation frequency of a taut and uniform string by either changing the string’s length, linear density, or tension. Most string musical instruments produce di↵erent tones by either altering string length (fretting) or playing preset and di↵erent string gages and string tensions. Although tension can be used to adjust the frequency of a string, it is typically only used in this way for fine tuning the preset tension needed to generate a specific note frequency. In this article, we present a novel string instrument concept that is able to continuously change the fundamental oscillation frequency of a plucked (or bowed) string by altering string tension in a controlled and predicted Email addresses: [email protected] (Ismet Handˇzi´c), [email protected] (Kyle B. Reed) URL: http://reedlab.eng.usf.edu/ () Preprint submitted to Applied Acoustics April 19, 2014 Figure 1: The musical kinetic shape variable tension string instrument prototype. -

Homo Aestheticus’

Conceptual Paper Glob J Arch & Anthropol Volume 11 Issue 3 - June 2020 Copyright © All rights are reserved by Shuchi Srivastava DOI: 10.19080/GJAA.2020.11.555815 Man and Artistic Expression: Emergence of ‘Homo Aestheticus’ Shuchi Srivastava* Department of Anthropology, National Post Graduate College, University of Lucknow, India Submission: May 30, 2020; Published: June 16, 2020 *Corresponding author: Shuchi Srivastava, Assistant Professor, Department of Anthropology, National Post Graduate College, An Autonomous College of University of Lucknow, Lucknow, India Abstract Man is a member of animal kingdom like all other animals but his unique feature is culture. Cultural activities involve art and artistic expressions which are the earliest methods of emotional manifestation through sign. The present paper deals with the origin of the artistic expression of the man, i.e. the emergence of ‘Homo aestheticus’ and discussed various related aspects. It is basically a conceptual paper; history of art begins with humanity. In his artistic instincts and attainments, man expressed his vigour, his ability to establish a gainful and optimistictherefore, mainlyrelationship the secondary with his environmentsources of data to humanizehave been nature. used for Their the behaviorsstudy. Overall as artists findings was reveal one of that the man selection is artistic characteristics by nature suitableand the for the progress of the human species. Evidence from extensive analysis of cave art and home art suggests that humans have also been ‘Homo aestheticus’ since their origins. Keywords: Man; Art; Artistic expression; Homo aestheticus; Prehistoric art; Palaeolithic art; Cave art; Home art Introduction ‘Sahityasangeetkalavihinah, Sakshatpashuh Maybe it was the time when some African apelike creatures to 7 million years ago, the first human ancestors were appeared. -

Fragile Gods: Ceramic Figurines in Roman Britain Volume 1

Fragile Gods: Ceramic Figurines in Roman Britain Volume 1 Thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Archaeology, University of Reading Matthew G. Fittock December 2017 Declaration I certify that this is my own work and that use of material from other sources has been properly and fully acknowledged in the text. I have read the University’s definition of plagiarism and the department’s advice on good academic practice. I understand that the consequence of committing plagiarism, if proven and in the absence of mitigating circumstances, may include failure in the Year or Part or removal from the membership of the University. I also certify that neither this piece of work, nor any part of it, has been submitted in connection with another assessment. Signature: Date: i Abstract As small portable forms of statuary, pipeclay objects provide a valuable insight into the religious beliefs and practices of the culturally mixed populations of the Roman provinces. This thesis provides a complete catalogue of the nearly 1000 published and unpublished pipeclay objects found in Britain, including figurines, busts, shrines, animal vessels and masks. This research is the first study of this material conducted since the late 1970s. Pipeclay objects were made in Gaul and the Rhine-Moselle region but not in Britain. Attention thus focuses on where and how the British finds were made by analysing their styles, types, fabrics and any makers’ marks. This reveals how the pipeclay market in Britain was supplied and how these objects were traded, and suggests that cultural rather than production and trade factors were more influential on pipeclay consumption in Britain. -

Paleolithic 3 Million + 10,000 BCE

The Rupture “This is where we should look for the earliest origins, long before the age of metals, because it was about 300,000 years ago that the “fire pit” was starting to be utilized with some stone, wood and bone.. Silo - 2004 Paleolithic 3 Million + 10,000 BCE The term Paleolithic refers to the « Old Stone Age » The Paleolithic period begins with the first evidence of human technology (stone tools) more than three million years ago, and ends with major changes in human societies instigated by the invention of agriculture and animal domestication. Paleolithic, Lower, Middle and Upper Lower Paleolithic 3 Million + - 300,000 BCE the Lower Paleolithic, from the earliest human presence (Homo antecessor and Homo heidelbergensis) to the Holstein interglacial, c. 1.4 to 0.3 million years ago. Middle Paleolithic 300,000 – 40,000 BCE the Middle Paleolithic, marked by the presence of Neanderthals, 300,000 to 40,000 years ago Upper Paleolithic 45,000 – 12,000 BCE the Upper Paleolithic, c. 45,000 to 12,000 years ago, marked by the arrival of anatomically modern humans and extending throughout the Last Glacial Maximum The Aurignacian Period – 40,000-28,000 BCE • The Aurignacian cultural tradition is generally accepted as the first modern humans in Europe. • During this period an explosion of sudden and innovative changes take place. People begin to use musical instruments which indicates possible ceremony, ritual and dance. Plus all forms of art appears at this time which signifies the full emergence of modern symbolic expression. • The most significant development in stone tool making is the refinement of the manufacture of blades struck off conical cores or nuculi. -

Re-Presentations of Palaeolithic Visual Imagery: Simulacra and Their Alternatives'

Re-Presentations of Palaeolithic Visual Imagery: Simulacra and their Alternatives' Marcia-Anne Dobres Introduction A long-standing methodological and epistemological split within Palaeolithic archaeology has led to what is recognized today as an unrealistic and highly problematic reconstruction of prehistoric people. My discussion is intended to unravel some of the many threads that have been used to weave this simulacrum, this "identical copy for which no original has ever existed" (Jameson 1984:66; following Beaudrillard 1983). The reasons for taking critical stock of ourselves and our interpretations lies in the fact that we unknowingly bring a multitude of paradigmatic and personal biases to our research that often systematically color our methodologies, our epistemologies, and our interpretations. More importantly, however, these biases often go undetected precisely because they are so systematic and ubiquitous. Legitimation of the present by referencing simulacra standing as the past becomes an issue of concern once we recognize the subtle yet powerful ways the past is part of our present. This important point is developed in detail below. It thus remains that we endeavor to be clear about what we say, and to consider long and hard the lines of reasoning we employ in reconstructing prehistoric life. In the spirit of constructive criticism then, this paper proposes to explore some of the sociopolitical and hiellectual contexts in which the study of prehistoric visual imagery has taken place - and continues to take place even today. I seek to understand not-only how these interpretations have been developed, but to consider their implications vis-a-vis the larger sociopolitical framework in which archaeology is practiced. -

A Gis Tool to Demonstrate Ancient Harappan

A GIS TOOL TO DEMONSTRATE ANCIENT HARAPPAN CIVILIZATION _______________ A Thesis Presented to the Faculty of San Diego State University _______________ In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Science in Computer Science _______________ by Kesav Srinath Surapaneni Summer 2011 iii Copyright © 2011 by Kesav Srinath Surapaneni All Rights Reserved iv DEDICATION To my father Vijaya Nageswara rao Surapaneni, my mother Padmaja Surapaneni, and my family and friends who have always given me endless support and love. v ABSTRACT OF THE THESIS A GIS Tool to Demonstrate Ancient Harappan Civilization by Kesav Srinath Surapaneni Master of Science in Computer Science San Diego State University, 2011 The thesis focuses on the Harappan civilization and provides a better way to visualize the corresponding data on the map using the hotlink tool. This tool is made with the help of MOJO (Map Objects Java Objects) provided by ESRI. The MOJO coding to read in the data from CSV file, make a layer out of it, and create a new shape file is done. A suitable special marker symbol is used to show the locations that were found on a base map of India. A dot represents Harappan civilization links from where a user can navigate to corresponding web pages in response to a standard mouse click event. This thesis also discusses topics related to Indus valley civilization like its importance, occupations, society, religion and decline. This approach presents an effective learning tool for students by providing an interactive environment through features such as menus, help, map and tools like zoom in, zoom out, etc. -

Archery Notes

Archery Notes Description: Archery is a sport that involves the use of a bow and a number of arrows. The bow is used to shoot the arrows at targets. We will be shooting at stationary targets. This is referred to as ‘Target Archery’. Equipment: Bow: Length and weight varies with the individual (18-25 lbs. for class use: 20-30 lbs. for club use) The style of the bows vary – straight or recurve in Fiberglass, wood, and metal. Arrows: length according to length of arms of the archer (24-28 “). Wood, fiberglass, aluminum, carbon/alloy composite, and carbon fiber. Targets (butts): circular or square targets made of dense Target Butt or buttress: Material that can sustain the impact of the arrow. Straw, Styrofoam, compressed cardboard. Bow strings: dacron- single or double loop according to the type of bow. The center part of the string is wolven thicker to accommodate the nocking of the arrow. This is referred to as the serving. Rubber finger tabs (rolls) are also attached to the serving. A single roller on the upper section and a double on the lower section. Target Faces: thick paper with concentric circles that vary in colour from the outside in. The target is divided into 5 different coloured sections. Safety tackle: Arm guard for the inside of the bow arm. Quivers: ‘Arrow Holder’. Used to organize and hold arrows for the archer. Stringing the bow: Step through method (push-pull) Instructions 1. Slide the top loop of your bow string over the nock and down the limb about halfway, or as far as the loop will allow. -

String Instruments 1

String Instruments 1 STRINGS 318-1 Harp Technique and Pedagogy I (0.5 Unit) Pedagogical STRING INSTRUMENTS instruction and demonstration of teaching techniques for all levels and ages. music.northwestern.edu/academics/areas-of-study/strings STRINGS 318-2 Harp Technique and Pedagogy II (0.5 Unit) Pedagogical Majors in string instruments prepare for professional performance and instruction and demonstration of teaching techniques for all levels and teaching as well as for advanced study. The curriculum is built around ages. individual study and ensemble participation, including chamber music STRINGS 318-3 Harp Technique and Pedagogy III (0.5 Unit) Pedagogical and orchestra, with orchestral repertoire studies and string pedagogy instruction and demonstration of teaching techniques for all levels and available to qualified juniors and seniors. A junior recital and a senior ages. recital are required. Students in this program may major in violin, viola, STRINGS 319-1 Orchestral Repertoire I (Violin,Viola,Cello,Dbl Bass,Harp) cello, double bass, harp, or classical guitar. (0.5 Unit) Program of Study STRINGS 319-2 Orchestral Repertoire II (Violin,Viola,Cello,Dbl Bass,Harp) (0.5 Unit) • String Instruments Major (https://catalogs.northwestern.edu/ undergraduate/music/string-instruments/string-instruments-major/) STRINGS 319-3 Orchestral Repertoire III (Violin,Viola,Cello,Dbl Bass,Harp) (0.5 Unit) STRINGS 141-0 Applied Violin for Music Majors (1 Unit) STRINGS 335-0 Selected Topics (0.5-1 Unit) Topics vary; announced STRINGS 142-0 Applied Viola for