Gold Mining in Zululand1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Zululand District Municipality Integrated

ZULULAND DISTRICT MUNICIPALITY INTEGRATED DEVELOPMENT PLAN: 2020/2021 REVIEW Integrated Development Planning is an approach to planning that involves the entire municipality and its citizens in finding the best solutions to achieve good long- term development. OFFICE OF THE MUNICIPAL MANAGER [Email address] TABLE OF CONTENTS Page No. 1 INTRODUCTION .............................................................................................................................................. 1 1.1 Purpose .................................................................................................................................................................. 1 1.2 Introduction to the Zululand District Municipality ................................................................................................. 1 1.3 Objectives of the ZDM IDP...................................................................................................................................... 3 1.4 Scope of the Zululand District Municipality IDP ..................................................................................................... 4 1.5 Approach ................................................................................................................................................................ 5 1.6 Public Participation ................................................................................................................................................. 6 2 PLANNING AND DEVELOPMENT LEGISLATION AND POLICY ......................................................................... -

Annual Report 2015/2016

SOUTH AFRICAN POLICE SERVICE: VOTE 23 ANNUAL REPORT 2015/2016 ANNUAL REPORT 2015/16 SOUTH AFRICAN POLICE SERVICE VOTE 23 2015/16 ANNUAL REPORT REPORT ANNUAL www.saps.gov.za BACK TO BASICS TOWARDS A SAFER TOMORROW #CrimeMustFall A SOUTH AFRICAN POLICE SERVICE: VOTE 23 ANNUAL REPORT 2015/2016 B SOUTH AFRICAN POLICE SERVICE: VOTE 23 ANNUAL REPORT 2015/2016 Compiled by: SAPS Strategic Management Layout and Design: SAPS Corporate Communication Corporate Identity and Design Photographs: SAPS Corporate Communication Language Editing: SAPS Corporate Communication Further information on the Annual Report for the South African Police Service for 2015/2016 may be obtained from: SAPS Strategic Management (Head Office) Telephone: 012 393 3082 RP Number: RP188/2016 ISBN Number: 978-0-621-44668-5 i SOUTH AFRICAN POLICE SERVICE: VOTE 23 ANNUAL REPORT 2015/2016 SUBMISSION OF THE ANNUAL REPORT TO THE MINISTER OF POLICE Mr NPT Nhleko MINISTER OF POLICE I have the honour of submitting the Annual Report of the Department of Police for the period 1 April 2015 to 31 March 2016. LIEUTENANT GENERAL JK PHAHLANE Date: 31 August 2016 ii SOUTH AFRICAN POLICE SERVICE: VOTE 23 ANNUAL REPORT 2015/2016 CONTENTS PART A: GENERAL INFORMATION 1. GENERAL INFORMATION OF THE DEPARTMENT 1 2. LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS/ACRONYMS 2 3. FOREWORD BY THE MINISTER 7 4. DEPUTY MINISTER’S STATEMENT 10 5. REPORT OF THE ACCOUNTING OFFICER 13 6. STATEMENT OF RESPONSIBILITY AND CONFIRMATION OF ACCURACY FOR THE ANNUAL REPORT 24 7. STRATEGIC OVERVIEW 25 7.1 VISION 25 7.2 MISSION 25 7.3 VALUES 25 7.4 CODE OF CONDUCT 25 8. -

Biodiversity Sector Plan for the Zululand District Municipality, Kwazulu-Natal

EZEMVELO KZN WILDLIFE Biodiversity Sector Plan for the Zululand District Municipality, KwaZulu-Natal Technical Report February 2010 The Project Team Thorn-Ex cc (Environmental Services) PO Box 800, Hilton, 3245 Pietermaritzbur South Africa Tel: (033) 3431814 Fax: (033) 3431819 Mobile: 084 5014665 [email protected] Marita Thornhill (Project Management & Coordination) AFZELIA Environmental Consultants cc KwaZulu-Natal Western Cape PO Box 95 PO Box 3397 Hilton 3245 Cape Town 8000 Tel: 033 3432931/32 Tel: 072 3900686 Fax: 033 3432033 or Fax: 086 5132112 086 5170900 Mobile: 084 6756052 [email protected] [email protected] Wolfgang Kanz (Biodiversity Specialist Coordinator) John Richardson (GIS) Monde Nembula (Social Facilitation) Tim O’Connor & Associates P.O.Box 379 Hilton 3245 South Africa Tel/ Fax: 27-(0)33-3433491 [email protected] Tim O’Connor (Biodiversity Expert Advice) Zululand Biodiversity Sector Plan (February 2010) 1 Executive Summary The Biodiversity Act introduced several legislated planning tools to assist with the management and conservation of South Africa’s biological diversity. These include the declaration of “Bioregions” and the publication of “Bioregional Plans”. Bioregional plans are usually an output of a systematic spatial conservation assessment of a region. They identify areas of conservation priority, and constraints and opportunities for implementation of the plan. The precursor to a Bioregional Plan is a Biodiversity Sector Plan (BSP), which is the official reference for biodiversity priorities to be taken into account in land-use planning and decision-making by all sectors within the District Municipality. The overall aim is to avoid the loss of natural habitat in Critical Biodiversity Areas (CBAs) and prevent the degradation of Ecological Support Areas (ESAs), while encouraging sustainable development in Other Natural Areas. -

KZN Zusub 02022018 Uphong

!C !C^ ñ!.!C !C $ !C^ ^ ^ !C !C !C !C !C ^ !C ^ !C !C^ !C !C !C !C !C ^ !C ñ !C !C !C !C !C !C ^ !C ^ !C !C $ !C ^ !C !C !C !C !C !C ^!C ^ !C !C ñ !C !C !C !C !C !C !C !C !C !C !. !C ^ ^ !C ñ !C !C !C !C !C ^$ !C !C ^ !C !C !C !C ñ !C !C !C !C ^ !C !.ñ !C ñ !C !C ^ !C ^ !C ^ !C ^ !C !C !C !C !C !C !C !C ñ ^ !C !C !C !C !C ^ !C ñ !C !C ñ !C !C !C !C !C !C !C !C !C !C !C !C ñ !C !C ^ ^ !C !C !. !C !C ñ ^!C ^ !C !C !C ñ ^ !C !C ^ $ ^$!C ^ !C !C !C !C !C !C !C !C !C !C !C !C !. !C !.^ ñ $ !C !C !C !C ^ !C !C !C $ !C ^ !C $ !C !C !C ñ $ !C !. !C !C !C !C !C ñ!C!. ^ ^ ^ !C $!. !C^ !C !C !C !C !C !C !C !C !C !C !C !C !C !C !. !C !C !C !C ^ !.!C !C !C !C ñ !C !C ^ñ !C !C !C ñ !.^ !C !C !C !C !C !C !C !C ^ !Cñ ^$ ^ !C ñ !C ñ!C!.^ !C !. !C !C ^ ^ ñ !. !C !C $^ ^ñ ^ !C ^ ñ ^ ^ !C !C !C !C !C !C !C ^ !C !C !C !C !C !C !C !C !. !C ^ !C $ !. ñ!C !C !C ^ !C ñ!.^ !C !C !C !C !C !C !C !C $!C ^!. !. !. !C ^ !C !C !. !C ^ !C !C ^ !C ñ!C !C !. !C $^ !C !C !C !C !C !C !. -

KZN Amsub Sept2017 Emadla

!C ^ ñ!.C! !C $ ^!C ^ ^ !C !C !C !C !C ^ !C !C ^ !C^ !C !C !C !C !C ^ !C ñ !C !C !C !C !C !C ^ !C ^ !C !C $ !C ^ !C !C !C !C !C !C !C ^ ^ !C ñ !C !C !C !C !C !C !C !C !C !C !C !. !C ^ ^ !C ñ !C !C !C !C !C ^$ !C !C ^ !C !C !C !C ñ !C !C !C ^ ñ!.!C !C ñ!C !C !C ^ !C !C ^ ^ !C ^ !C !C !C !C !C !C !C !C ^ !C !C !C ñ !C !C ^ !C ñ !C !C !C ñ !C !C !C !C !C !C !C !C !C !C !C ñ !C !C ^ ^ !C !C !. !C !C ñ ^!C !C ^ !C !C ñ ^ !C !C ^ $ ^$!C ^ !C !C !C !C !C !C !C !C !C !C !C !C !. !C ^ ñ!. $ !C !C !C !C ^ !C !C !C !C $ ^ !C $ !C !C !C ñ $ !C !. !C !C !C !C !C ñ!C!. ^ ^ ^ !C $!. !C^ !C !C !C !C !C !C !C !C !C !C !C !C !C!C !. !C !C !C !C ^ !C !C !.ñ!C !C !C !C ^ñ !C !C ñ !C ^ !C !C !C!. !C !C !C !C !C ^ ^ !C !Cñ ^$ ñ !C ñ!C!.^ !C !. !C !C ^ ^ ñ !. !C $^ ^ñ!C ^ !C ^ ñ ^ ^ !C !C !C !C !C !C ^ !C !C !C !C !C !C !C !C !C !. !C ^ !C $ !. ñ!C !C !C ^ ñ!C.^ !C !C !C !C !C !C !C !C $!C ^!. !. !. !C ^ !C !C!. ^ !C !C^ !C !C !C !C ñ !C !. $^ !C !C !C !C !C !C !. -

Threatened Ecosystems in South Africa: Descriptions and Maps

Threatened Ecosystems in South Africa: Descriptions and Maps DRAFT May 2009 South African National Biodiversity Institute Department of Environmental Affairs and Tourism Contents List of tables .............................................................................................................................. vii List of figures............................................................................................................................. vii 1 Introduction .......................................................................................................................... 8 2 Criteria for identifying threatened ecosystems............................................................... 10 3 Summary of listed ecosystems ........................................................................................ 12 4 Descriptions and individual maps of threatened ecosystems ...................................... 14 4.1 Explanation of descriptions ........................................................................................................ 14 4.2 Listed threatened ecosystems ................................................................................................... 16 4.2.1 Critically Endangered (CR) ................................................................................................................ 16 1. Atlantis Sand Fynbos (FFd 4) .......................................................................................................................... 16 2. Blesbokspruit Highveld Grassland -

Chapter 4: the Business Sector

ZULULAND LED FRAMEWORK FINAL DRAFT PHASE 3: BUSINESS SECTOR REPORT CHAPTER 4: THE BUSINESS SECTOR 1. INTRODUCTION 1.1 PURPOSE OF REPORT Chapter 4 of the Status Quo Report forms part of the Phase 3 product of the Zululand Coordinated Local Economic Development Framework project focussing specifically on the Business Sector. Whereas Chapter 1 of the report provides a general introduction to local economic development and the context for local economic, Chapters 3 to 4 of the document presents a status quo analysis of what has been identified as the key economic sectors in the Zululand District Municipality, the sectors being respectively the Tourism Sector (Chapter 2), the Agricultural Sector (Chapter 3) and the Business Sector (Chapter 4). Although the Status Quo Report is structured on a sectoral basis it is widely acknowledged that close linkages exists between the various sectors and economic development activities within each of the broad sectors. These linkages will be addressed in more detail in Phase 4 of the project, the strategy development phase. The Business Sector Status Quo Report is aimed at providing: an overview of current activities within the business sector and highlighting key issues impacting on the development of the sector; an evaluation of the potential for the future development of the sector; and an identification of key opportunities relating to the sector. 1.2 DEFINING THE SECTOR The Business Sector, as defined for the purpose of this project, does not relate to any established industrial sector classification system. The Business Sector does, however, include a number of generally recognised industry sectors including commerce, manufacturing, construction, transport and mining. -

Basic Assessment for the Proposed Babanango Travelers Camp, Adjacent to the White Mfolozi River, Ulundi Local Municipality, Zululand District, Kwazulu-Natal

Basic Assessment for the Proposed Babanango Travelers Camp, Adjacent to the White Mfolozi River, Ulundi Local Municipality, Zululand District, KwaZulu-Natal Consultation (Draft) Basic Assessment Report for Comment July 2020 Prepare for: Emcakwini Community Trust 19 Wilson Street, Babanango, 3850 Northern KwaZulu-Natal Prepared by: Integrated Development Management Services Environmental (IDME) Consultants Ocean Dune, FMI House, 2 Heleza Boulevard Hillhead Umhlanga, 4320 i Client: Emcakwini Community Trust (ECT) Reference Document as: Basic Assessment for the Proposed Babanango Travelers Camp, Babanango Game Reserve, KwaZulu- Natal, Draft I for Comment, IDME, 2020 Client Reference Number: Babanango Travelers Camp Competent Authority Reference: To be issued Report Compiled by: Novashni Sharleen Moodley Pr.Sci.Nat Date of Report: July 2020 Report reviewed and approved by: Karl Wiggishoff Applicant: Emcakwini Community Trust Competent Authority: The Department of Economic Development, Tourism and Environmental Affairs (EDTEA) Environmental Assessment Practitioner (EAP): Novashni Sharleen Moodley of IDM Environmental Ocean Dune, FMI House, 2 Heleza Boulevard Hillhead Umhlanga, Sibaya Precinct, 4320 [email protected] i NOTICE This document and its appendices are a public document and made available to the Competent Authority (CA), commenting authorities, stakeholders, Interested and Affected Parties (I&APs), and the general public. This Consultation Basic Assessment Report (cBAR) is available for comment for a period of 30 days from 30 July to 30 August 2020. This report will then be amended and updated in response to the comments received during this review period. Once finalised the BAR will be submitted to the KwaZulu-Natal Department of Economic Development, Tourism and Environmental Affairs, Zululand District (KZN EDTEA), for decision-making. -

Export This Category As A

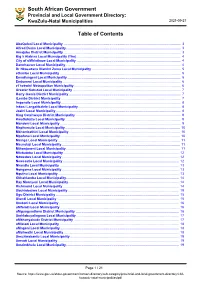

South African Government Provincial and Local Government Directory: KwaZulu-Natal Municipalities 2021-09-27 Table of Contents AbaQulusi Local Municipality .............................................................................................................................. 3 Alfred Duma Local Municipality ........................................................................................................................... 3 Amajuba District Municipality .............................................................................................................................. 3 Big 5 Hlabisa Local Municipality (The) ................................................................................................................ 4 City of uMhlathuze Local Municipality ................................................................................................................ 4 Dannhauser Local Municipality ............................................................................................................................ 4 Dr Nkosazana Dlamini Zuma Local Municipality ................................................................................................ 5 eDumbe Local Municipality .................................................................................................................................. 5 Emadlangeni Local Municipality .......................................................................................................................... 6 Endumeni Local Municipality .............................................................................................................................. -

Babanango-Game-Reserve-Guest-Information

GUEST INFORMATION 1 CONTENTS 3 Welcome 4 About African Habitat Conservancy 5 Babanango Game Reserve – overview and values. 7 Babanango Valley Lodge overview 8 From Cop to Cook 9 Activities 11 Babanango Valley Lodge Specifics 14 The Rest of the Reserve 15 Babanango Game Reserve rules 18 Children at Babanango Game Reserve 19 Places of interest 20 Lodge layout 21 Map 2 SAWUBONA AND WELCOME TO BABANANGO GAME RESERVE Tucked away in the rolling hills of northern KwaZulu-Natal, with a history dating back to the origins of the Zulu nation, Babanango Game Reserve is a trailblazing success story that’s protecting a vast African wilderness while uplifting rural community in the process... “Nothing but breathing the air of Africa, and walking through it, can communicate the indescribable sensations.” - William Burchell 3 AFRICAN HABITAT CONSERVANCY About African Habitat Conservency African Habitat Conservancy (AHC) was established to support the conservation of African wildlife through sustainable investment in central KwaZulu-Natal in South Africa. The first African Habitat Conservancy project, Babanango Game Reserve, consists of 22,000ha of pristine wilderness encompassing rich biodiversity and plenty of room for growth for many species of flora and fauna, including the Big Five. As the reserve falls within the Umfolozi Biodiversity Economy Node (UBEN), a region that is in dire need of socio-economic upliftment, AHC has founded a trust - the African Habitat Conservancy Foundation (AHCF) to support the ongoing upliftment of the local communities, through the development of several exclusive lodges and tented camps offering accommodation, game viewing and outdoor education facilities. AHC offers education, training, employment and entrepreneurial opportunities to the surrounding communities. -

Rural Urban Studies Unit Development Studies Unit

RURAL URBAN STUDIES UNIT UNIVERSITY OF NATAL DURBAN K5 — A PRELIMINARY STUDY OF AN INFORMAL RURAL SETTLEMENT flNiSTi i'UTE OF 1 6 JUN1988 I DEVELOPMENT STUDIES LIBRARY — S E Stavrou, D Z Mbona and X S Yokwe, C F Mbona DEVELOPMENT STUDIES UNIT Centre for Applied Social Sciences WORKING PAPER NO. Efl Rural Urban Studies Unit The Rural Urban Studies Unit was founded in 1983 by the Human Sciences Research Council for the purpose of studying the dynamics of the links between the rural and urban areas of South Africa. It is situated at the University of Natal, Durban and works in close co-operation with the Development Studies Unit. ISBN NO: 0-86980-593-2 K5 - a preliminary study of an informal rural settlement1 Introduction It has been argued that the apartheid period up to the end of the ]950's can be broadly characterized as one of allocation of labour whilst that of the 1960's and ]970's as the decades of relocation of labour (Mart, 1979:37). From the earliest times of European settlement in the Cape to the present, the procurement of labour in South Africa has almost always been a central theme in the policy planninq of successive governments. The provision and stability of both industrial and aqrarian labour has remained at the core of most of these state policies, although the emphasis and direction of this policy has periodically altered. From the middle of the last century a policy of separate residential and agricultural areas, based on racial criteria, was initiated by the Natal Administration. -

Kwazulu-Natal

KwaZulu-Natal Municipality Ward Voting District Voting Station Name Latitude Longitude Address KZN435 - Umzimkhulu 54305001 11830014 INDAWANA PRIMARY SCHOOL -29.99047 29.45013 NEXT NDAWANA SENIOR SECONDARY ELUSUTHU VILLAGE, NDAWANA A/A UMZIMKULU KZN435 - Umzimkhulu 54305001 11830025 MANGENI JUNIOR SECONDARY SCHOOL -30.06311 29.53322 MANGENI VILLAGE UMZIMKULU KZN435 - Umzimkhulu 54305001 11830081 DELAMZI JUNIOR SECONDARY SCHOOL -30.09754 29.58091 DELAMUZI UMZIMKULU KZN435 - Umzimkhulu 54305001 11830799 LUKHASINI PRIMARY SCHOOL -30.07072 29.60652 ELUKHASINI LUKHASINI A/A UMZIMKULU KZN435 - Umzimkhulu 54305001 11830878 TSAWULE JUNIOR SECONDARY SCHOOL -30.05437 29.47796 TSAWULE TSAWULE UMZIMKHULU RURAL KZN435 - Umzimkhulu 54305001 11830889 ST PATRIC JUNIOR SECONDARY SCHOOL -30.07164 29.56811 KHAYEKA KHAYEKA UMZIMKULU KZN435 - Umzimkhulu 54305001 11830890 MGANU JUNIOR SECONDARY SCHOOL -29.98561 29.47094 NGWAGWANE VILLAGE NGWAGWANE UMZIMKULU KZN435 - Umzimkhulu 54305001 11831497 NDAWANA PRIMARY SCHOOL -29.98091 29.435 NEXT TO WESSEL CHURCH MPOPHOMENI LOCATION ,NDAWANA A/A UMZIMKHULU KZN435 - Umzimkhulu 54305002 11830058 CORINTH JUNIOR SECONDARY SCHOOL -30.09861 29.72274 CORINTH LOC UMZIMKULU KZN435 - Umzimkhulu 54305002 11830069 ENGWAQA JUNIOR SECONDARY SCHOOL -30.13608 29.65713 ENGWAQA LOC ENGWAQA UMZIMKULU KZN435 - Umzimkhulu 54305002 11830867 NYANISWENI JUNIOR SECONDARY SCHOOL -30.11541 29.67829 ENYANISWENI VILLAGE NYANISWENI UMZIMKULU KZN435 - Umzimkhulu 54305002 11830913 EDGERTON PRIMARY SCHOOL -30.10827 29.6547 EDGERTON EDGETON UMZIMKHULU